The Bibliophile of Standish and Montignac Toupinerie: Brian J. Birch

An interview with the great British philatelic bibliographer

This article was first published as “The Bibliophile of Standish and Montignac Toupinerie: Brian J. Birch.” Philatelic Literature Review 70 no. 2 (Second Quarter 2021)

An excerpt of the interview was published as “The Bibliophile of Standish and Montignac Toupinerie: Brian J. Birch.” The American Philatelist 135 no. 8 (August 2021)

It was also translated into German and republished (along with the English version) as “Der Bibliophile von Standish und Montignac Toupinerie: Brian J. Birch.” The Philatelic Journalist whole no. 166 (October 2021)

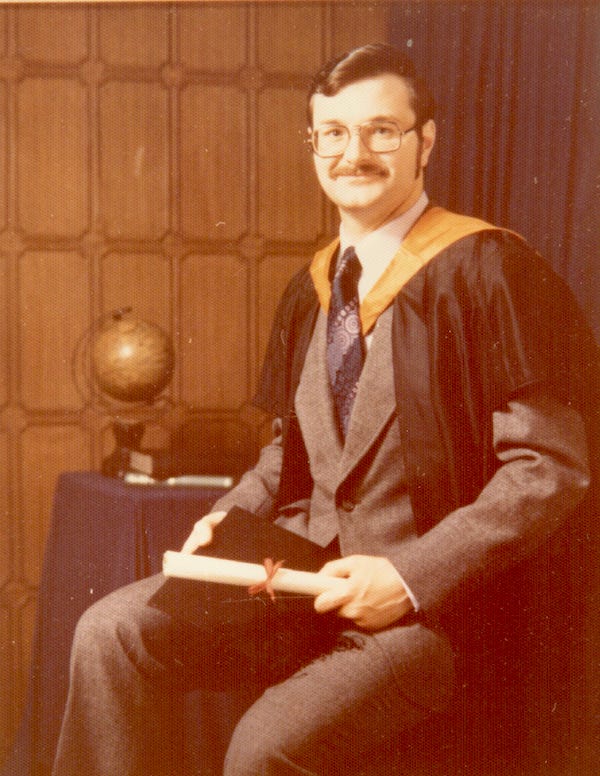

In the world of philatelic literature, Brian Birch (Figure 1) stands tall. Following in the footsteps of renowned bibliophiles and recorders of the past like P. J. Anderson, B. T. K. Smith, E. D. Bacon, Fred. J. Melville, the Williams brothers, and the Negus brothers, today Birch is one of the extremely few exclusive proponents of philatelic bibliography and history. Birch’s prodigious output over the last three decades consists of tens of thousands of pages. The vast scope of his Philatelic Bibliophile’s Companion needs to be seen to be believed; I keep discovering new aspects every so often.

I first read of Birch in the book Milestones of the Philatelic Literature of the 19th Century.1 Later I began corresponding with him but have not had the fortune to meet him. I was looking forward to it at Stockholmia 2019, but Birch could not attend due to illness. I can think of no better person to inaugurate this new series on philatelic bibliophiles of the world. Birch has much wisdom to share and hence my introduction must be necessarily short.

Brian, tell us about yourself.

I was born Brian John Birch on January 18, 1949, at Liverpool. My father was Frederick Birch, a policeman in the Liverpool Force, and my mother was Edna May Birch, a hairdresser and later shopkeeper. I had an older brother, David Frederick Birch, born in 1946, who also became a policeman (Figure 2). I met my future wife, Marion Eslick, at university. We have two children, Sally and Geoffrey.

Following schooling, I attended the Department of Metallurgy at the University of Liverpool in 1967, graduating three years later. Following two years of research, I received my Master of Engineering degree. I moved to the University of Aston in Birmingham as a Technical Information Officer at the newly-opened Wolfson Heat Treatment Centre and spent the next two years there. I eventually left to join a small private company, Nemo Heat Treatments Ltd. In 1983, Nemo was taken over by the industry leader, Blandburgh, part of Bodycote International plc, a large multinational conglomerate. I spent the remainder of my career with Bodycote managing various plants and ended my time there as Director of Health, Safety and Environmental Compliance in 2009 after 31 years of service.

How did you get into the hobby?

When I was nine, my father gave my brother and I a stamp album each and a set of stamps. I still remember my set – East German cancelled-to-order flowers issued in 1957. We collected in tandem for many years, trying hard not to compete and in the end, he kept only France and Germany and the other countries became mine. I was always the more interested in philately whilst he basically stopped collecting when he joined the police force and, a few years later, got married.

At the age of 11, after primary school, I moved to Alsop Grammar School in the Aintree district of Liverpool. After a couple of years, I was introduced to the school’s stamp club, which was run by the Head of the Spanish Department. During my years at the University (Figure 3), I kept my collection up but obviously at a lower level of intensity.

Eventually, family life and increased commitments at work led to the stamps being laid aside for extended periods of time. Inevitably, during these low periods, I even neglected new issues and this led to my loss of interest in a collection getting ever further from completion.

You must be one of the few philatelists in the world interested only in the research and collection of philatelic literature and not in philately or postal history. How did you settle on your present interests?

As part of my training at Wolfson, I was sent to the British Library depot at Boston Spa, near Leeds, on a course of information science in 1973. Here I was seriously introduced to literature in all of its forms and was inspired to look more towards the literature than the stamps. The transition was fairly easy. As a collector of the whole of the Commonwealth, I could not aspire to anything like a complete collection on my salary and I enjoyed stamps so generally that I could never decide to specialise in any particular countries. So, my interest in collecting stamps began to subside and was eventually abandoned as my interest in the literature increased.

Your love of philatelic literature research started at the Perfin Society. How?

In 1971, I joined the then-named Security Endorsement and Perfin Society (SEPS) of Great Britain. A couple of years later a new librarian was required. This was an excellent opportunity so soon after my training at the British Library.

Naturally, I began to expand the library with both articles from philatelic magazines and books and pamphlets. The library had been accompanied by a Library List and I considered making a new one. However, the difficulty was that the library was increasing in size so rapidly that it would be very quickly out of date. Also, in a specialised library the depth of indexing would have to be such that even small pieces of important information could be retrieved.

At work, in those pre-personal computer days, I was taking relevant literature, producing an abstract and indexing it using punch-cards. Not wishing to set up too elaborate a system, I created Perfins Abstracts. For each item in the library, I assigned it a number, created an abstract of its contents, and indexed it using 3 x 5 inch cards. Occasionally, I had an index to the cards typed up by my sister-in-law so that I could distribute an alphabetical index to each of the members. This innovation led the notable British bibliophile James Negus to join the Society and gave rise to a lifelong friendship.

Although I gave the library up decades ago (in 1984) and no longer collect perfins, I have retained my membership of the renamed Perfin Society and am still the largest contributor to the library, sending the Society every relevant article I come across.

How did you start collecting philatelic literature?

With no collection to support, the standard monographs and handbooks held little interest for me and I chose to specialise in philatelic bibliography and the history of philately, its literature and its adherents. Even then I realised that collectors were often more interesting than their collections. I had no knowledge of the Earl of Crawford at that time, so my idea was to collect every piece of philatelic literature I came across. Harry Hayes’ literature auctions2 soon disabused me of that idea.

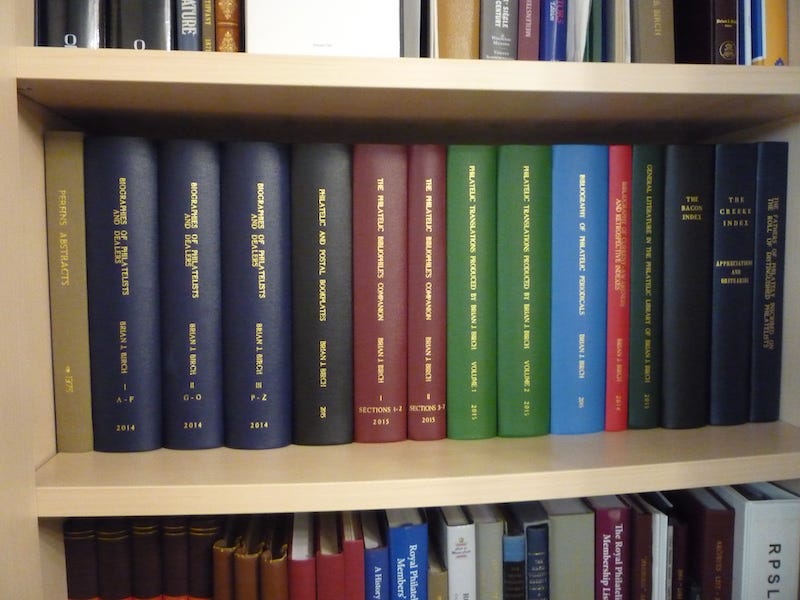

Your magnum opus is The Philatelic Bibliophile’s Companion and a couple of other long-term projects (Figure 4; also see Appendix). How did you start that?

The subject area I had chosen to specialise in was too vast to cover in a single list so that some simple classification was required. I looked at the typical general libraries’ classifications but these were far too general for me. Specialised philatelic “Subject heading” type listings produced by specialised philatelic libraries such as the American Philatelic Research Library and Cardinal Spellman Libraries concentrated on countries and other general terms of use to stamp collectors. I needed something specific to bibliophiles.

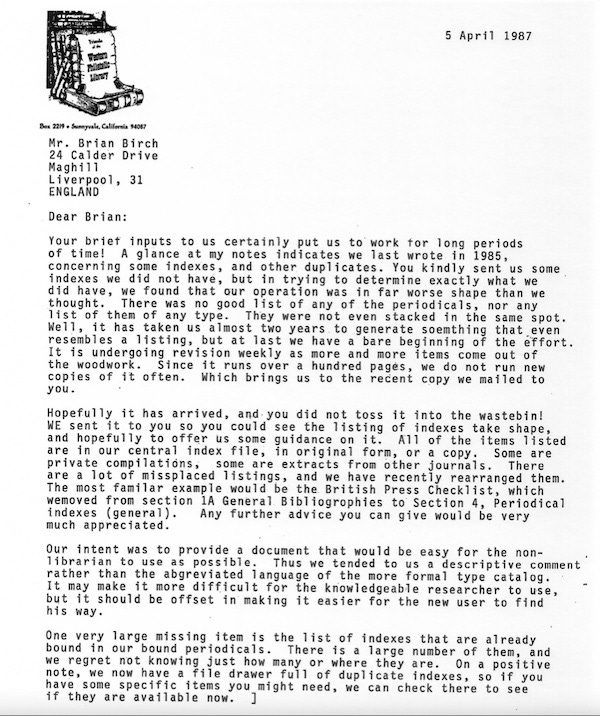

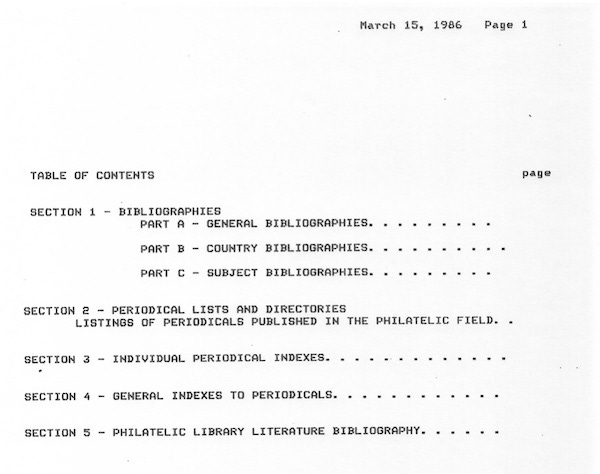

It was not until a decade or so later that I was forced to properly restructure my researches. Early in 1987 I received a package from Roger Skinner of Friends of the Western Philatelic Library (Figure 5). The package contained a substantial philatelic bibliography of bibliographic works arranged in five sections (I actually received only three). While corresponding with him, I realised that ultimate product would be a reference manual intended for the use of both bibliophiles and librarians. That’s how the idea of The Philatelic Bibliophile’s Companion was conceived – essentially as a Bibliography of Bibliographies, arranged according to subject.

Over the years, I revised the “Contents” list (Figure 5) extensively as I acquired additional items for my library and tried to fit them into my scheme. As recently as 2015, I added a further new section which came to my attention as I tried to fit Almanacs unsuccessfully into one of the existing categories.

Why are your major projects only available as a soft copy?

Although I spent a great deal of time in compiling some of these over the past 40 or so years, it was evident that their scope is such that they would never be finished and so could never be conventionally published as a hard copy.

The Bibliophile was first uploaded on your own website and is now on the Global Philatelic Library’s site. How and why did it make this transition?

Each of my never-ending projects has required thousands of hours of my time to bring them to their current, very unfinished state. I hate the thought that if anything happened to me, this work could all be lost to posterity.

In the late 1990s, the answer was obvious – I had my own website, created by a colleague at work, www.philatelicliterature.org, and loaded all of my long-term projects onto it. However, the problem with a site of one’s own is time and, in the event, new versions of my works were never uploaded. Eventually my site closed due to my lack of time to maintain it.

Just after the turn of the century, my hard drive failed – this was following a major update of my works, six months after the last back-up. The next four or five months, as I strove to get the data recovered and re-build my computer, almost led me to completely abandon philatelic research; such was the extent of my disenchantment. A year or so later and quite unexpectedly, I received an email from Francis Kiddle, then President of the FIP Literature Commission. I had only met Francis once or twice at the Royal Philatelic Society London but had corresponded with him on numerous occasions during my researches. His mail advised me that the FIP Literature Commission was intending to set up a website and were looking for some material with which to populate it. As a result of the subsequent negotiations, most of my long-term works were uploaded on fipliterature.org.

Following the end of Anthony Virvilis’ tenure as president in 2016, I lost touch with the organization. Eventually, in 2018 I took up a long-standing invitation from Frank Walton, the Past President of the Royal Philatelic Society London, to host my works on the Society’s website or its associated Global Philatelic Library.3

Why do you get only one copy of your projects printed and bound? Further, why would you send a copy of every new edition of your Companion (see Appendix) to a different philatelic library in the world? Why not have it all in the same library so that one could compare its evolution?

Although the projects are only intended to exist in electronic form, I used to bind one copy for my personal use since it is much more convenient. Every year or so, I used to get the updated documents bound in a new “edition.” Since printing and binding is quite an expensive undertaking and the volumes take up a lot of shelf space, I used to donate the obsolete bound volumes to important philatelic libraries round the world. In May 2018, my wife and I moved permanently to live in France. Since I no longer had easy access to low-cost printing and binding, I no longer get copies bound on a regular basis.

I have been asked why I donate each edition to a different library rather than all to one library so that their evolution could be followed. The answer is in several parts: One, the evolution of my works is evident from my own notes contained in these works. Next, some philatelic libraries discard older editions when a new one is obtained, and many libraries lack the resources necessary for comparing editions. Further, as well as the bibliophile, my works are intended for the general philatelist who needs to be shown where to look for the information he needs. Finally, it is also a small thank you for all the help I have received from these libraries over the years.

You have also made a number of translations of various works not in English. Why and how did you do this?

The origin of the translations can be traced to the SEPS library which received at least two foreign-language periodicals on the subject of perfins and many individual articles. I decided that as I could not provide an abstract, they all had to be translated. In order to achieve this, I had to find a philatelic translation service. The only one of which I was aware was that of the American Philatelic Society. So it was that in 1976 I joined the APS solely to use their translation service. By the time I had given up the SEPS library in 1984, the number of translations, which I had labelled SEPS Trans, had reached 260.

In 1967, at Liverpool University, I met Betty Howarth, where she was in charge of all the Engineering Libraries. From 1972 to 2003, Betty did around 1,000 translations for me including a bit under 500 philatelic articles, extracts of books, and even complete books; she never accepted any compensation for this and I am forever in her debt.

When I retired, my secretary, Anne Drinkwater, also retired but she has graciously typed up my handwritten notes ever since. I cannot take a computer everywhere with me but I can take a pad and pen. Rather than me labouriously typing these up with two fingers, I email them to Anne and she types them up for me. I recently found that she can just as easily type in German, French, Italian, etc., so I can get her typescript, put it into Google Translate and edit into a reasonably understandable text. I only use the APS translation service for difficult languages now. The translations I produce for my own interest are called the Philat. Trans. Series and currently number 800 translations, varying from minor, half-a-dozen line pieces to substantial parts of books. They are all incorporated into my work Philatelic Translations Produced by Brian J. Birch.

How did you get interested in indexes?

My attempts to expand the SEPS library gave me an insight into the power of indexes to periodicals, particularly cumulative indexes. It is so much easier to look up perfins in a cumulative index than to look through a dozen or two annual indexes – not every periodical is blessed with one of those – or, God forbid, to scan the journal page by page. I quickly found that occasionally, before the number of journals became overwhelming, some brave souls attempted to index all of the most important journals published to date – so-called retrospective indexes. I quickly acquired every cumulative and retrospective index that I could lay my hands on. Initially, I listed cumulative indexes in its own bibliography but soon realised that I was duplicating much of the data from my bibliography of periodicals. Accordingly, I combined the two documents. The retrospective and current awareness indexes were always kept in a separate document.4

You collect limited numbered edition of philatelic bibliographies and also record their current ownership. How do you manage to do so?

Just before I became engrossed in philatelic literature came what are probably the most important series of philatelic literature auction sales ever. Starting in 1950 with the W. R. King Library, through the three Ralph A. Kimble sales to the David Lidman library of 1972, Sylvester Colby held a series of literature sales. Their importance lies not only in that they included 14 of the most important American (and one English) libraries formed in the first half of the 20th century, but that they were all probably originally purchased by George T. Turner and described by him. Turner was the greatest bibliophile of the 20th century.

As I looked through the bibliographic section of the catalogue, I noticed individual books which were in limited and numbered editions. This piqued my interest and I looked specially for these whenever I received a literature list or auction catalogue. On receipt, I found that some were signed by the author and dedicated to the first recipient. Turner had added this information to his descriptions and so I began to compile a list of owners. I wrote to all major libraries and anyone else who was likely to have a copy and so my list grew. Few bibliophiles describe books nowadays and even fewer know what to look for so my list barely grows at all now.

Moving on to your other publications, the earliest article that I can find that you published in the Philatelic Literature Review is from 1987. But you have been publishing from the 1970s, haven’t you? What were those publications?

I have been writing articles since 1973, although that decade and much of the next was largely taken up by my work for the SEPS and these were generally minor pieces. Many of them are missing from my files. I have only recently obtained a fairly complete set of the Society Bulletins and am in the middle of adding these items to my list of articles.

You have won the Thomas F. Allen award for the best article published in a single year of the Philatelic Literature Review thrice, in 2012, 2013, and 2015. I particularly liked the one on whether it was Theodore F. Cuno or Schuyler B. Bradt who formed the American Philatelic Society. Now, which are some of your articles that gave you the most satisfaction?

It is impossible to say really as I am never satisfied with any of my articles; they could always be better. In reality, my search for perfection – for all of the facts, for every article that needs referencing, etc. leads to a fear of publishing anything. So, one bites the bullet and publishes, however imperfect it might be.

On the subject of philatelic bibliography, most philatelists (not me!) would consider it dull. So why do you do what you do? What keeps you interested in it despite knowing that the number of philatelists following your work would be a small fraction of those out there?

Everything I do is for my own satisfaction, amusement, and relaxation and is not dependent on the approval of others. That others might appreciate them is an added bonus. I am not a fan of Facebook-type approvals where the number of “likes” counts for everything.

Whilst working on research at the University of Liverpool, I remember reading that, “more discoveries are made in a library than in a laboratory”. What this means in practice is that what is known is then forgotten over several lifetimes only to be rediscovered later. So it is with philately. Today’s philatelists have forgotten much that was known to early stamp collectors. I realised this when researching my book – The Fathers of Philately – for which most of the information came from 19th century periodicals, right back to the 1860s and 70s. The simple answer is that I am never bored and learn something new every time I read one of my early magazines or books.

Could you name a few of your favourite works?

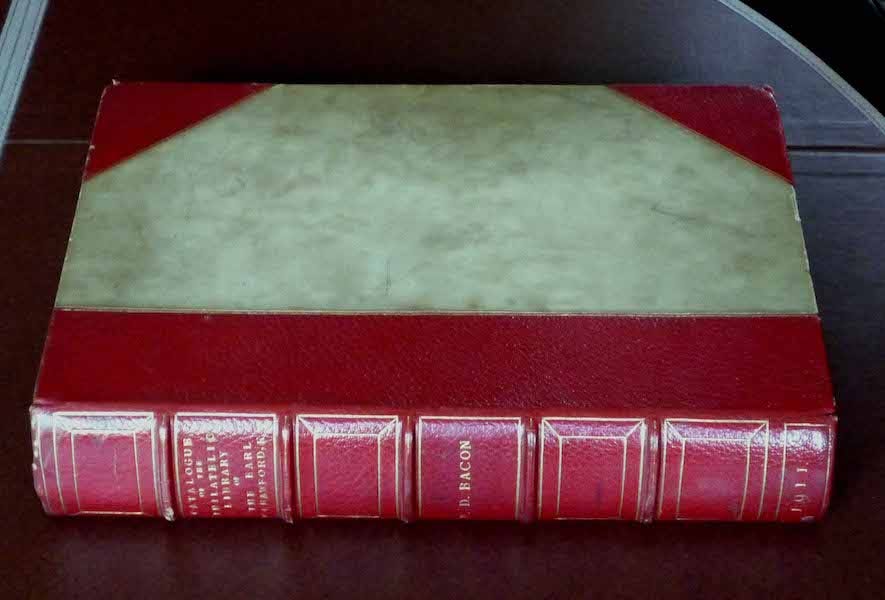

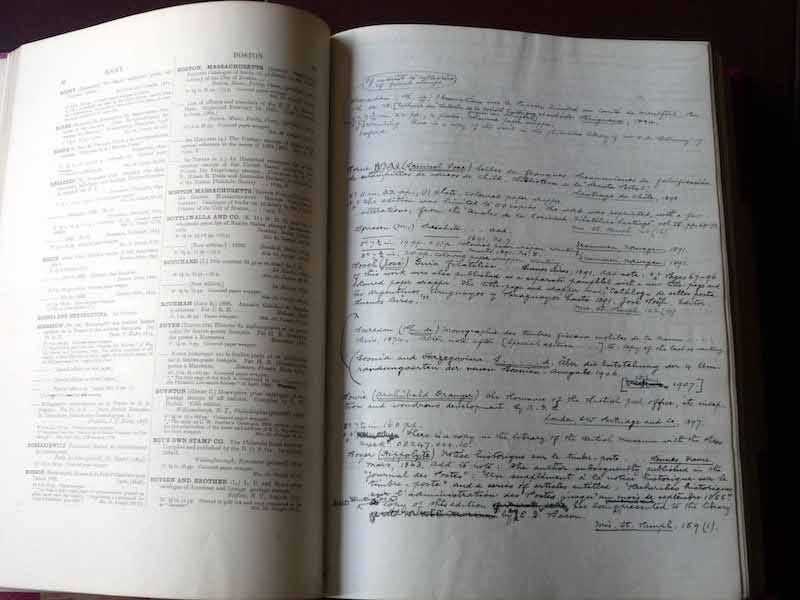

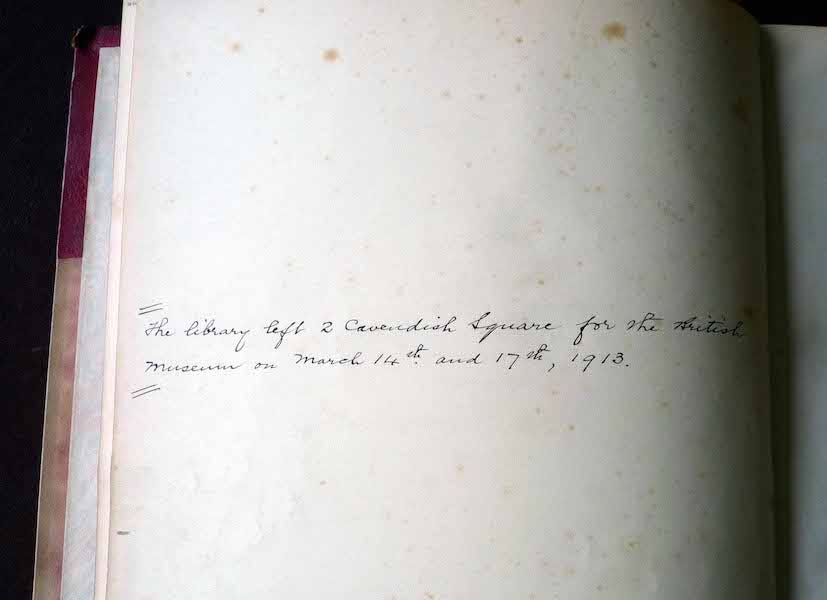

First on my list is the Crawford Catalogue. (Figure 6).5

This is so much more than a library catalogue. Bacon included a vast amount of useful information so that it is the first point of reference on any periodical published up to the end of 1906 and any separate work published up to the end 1908. He also included details of works that the Earl of Crawford was unable to obtain during his lifetime.

Following the death of the Earl, Bacon continued to record corrections and new data up to the time of his death. He also made many donations to the Library of missing items. Unfortunately, many of those failed to reach the Crawford Library and were simply added to the British Museum’s general library. I own Bacon’s personal interleaved copy of the Philatelic Literature Society’s edition, sumptuously half-bound in red leather. The blank interleaved pages contain details of all of the new information Bacon had been able to gather.

Another book I like is Ronald Butler’s on the signatories to the Roll of Distinguished Philatelists.6 It is a compendium of concise biographical notes on most of the great philatelists of the 20th century, many of which include photographs. It is the first resource to consult when looking for information on important philatelists. In 2013, I was advised by the then Keeper of the Roll, Chris King, that a new more-comprehensive edition of this book was planned. He asked whether I would produce an improved introductory section on the Fathers of Philately. Over the next many years, with help from Chris and Tomas Bjäringer, I compiled 43 more-or less comprehensive biographies of the Fathers. By the time the work was finished, it dwarfed Butler’s original book (211 pages to 300 larger format pages) and it was decided to publish it as it stood.7

Finally, I would mention James Negus’ book on philatelic literature.8 I could go on but will stop here!

In 2018, your vociferous views on works being published in digital format was published in The London Philatelist and started a nice little debate. Why did you feel so strongly about the subject that you wrote it whilst on a hospital bed recovering from a heart attack?

My objection stemmed from the “taken for granted” attitude of the publisher that digital publishing would replace the printed page. As a user of digital publishing for 30 years, I know that it has its place; however, it is not a panacea and authors have a right to see their works in print.

These days (some) web pages get archived (one such website is archive.org). This can only improve in the future, such that even defunct websites can be found elsewhere on the net. Not to mention philatelic and other works. Would you still hold on to your views in such a situation?

Whatever one looks for will not be archived where one looks. The web is full of dross.9

You mentioned over our call that you love the way the American Philatelic Research Library (APRL) helps you with your research work. I am sure you must have visited many philatelic libraries in your lifetime. Which are your favourite ones?

As I got interested in bibliography in the 1970s, I joined all of the philatelic libraries I could find. APRL, Northwest Philatelic Library (NWPL), Rocky Mountain Philatelic Library, and San Diego Philatelic Library – all in the United States; also, the Philatelistisches Bibliothek in Hamburg, Germany. I also enrolled in those societies that had large and long-established libraries – Collectors Club of New York, National Philatelic Society, Royal Philatelic Society London, PHILAS, and the Royal Sydney Philatelic Club. At one time or another, I used all of these facilities to further my researches.

In general, my working life involved so much travel that I only ever got to visit the RPSL and the National Philatelic Society libraries, both of which are in London; the latter is now combined with the RPSL’s library. All libraries have been helpful to me over the years but only the APRL is properly set up to assist patrons who are a long distance away.

In recent times, many society libraries are being disposed of due to space issues or lack of volunteers. For example, and as you mentioned, in 2019 the library of the National Philatelic Society was merged with that of The Royal Philatelic Society London and the duplicates sold through Cavendish Auctions. What do you make of this situation? Is information and access to it getting concentrated in a few big libraries?

The era of the general collector is over. There is no need for local societies to have large general libraries which are difficult and expensive to house and keep up to date. Specialists should be able to afford to purchase the books they require or join a specialised society, which can afford to keep a substantial library of its specialization.

The problem arises when the specialist society disposes of its library. Books of great rarity may be disposed of thoughtlessly, as happened recently with the British Society of Russian Philately. A couple of years ago its library was boxed up and more-or-less dumped on HH Sales. The key items, mostly early Russian material, was snapped up by the Rossica Society of Russian Philately in the United States. This material is therefore lost to future Russian specialists in the UK. Thought for the future should be given before the disposal of specialised libraries.

You mentioned to me about one researcher whose 650 pages of research work was thrown away when he died. What can be done to preserve such unpublished works?

The collector had 650 kg, not pages, thrown away! Collectors know what they have and should make arrangements for what happens to their archives after their death. Relatives will routinely get a skip in and throw it all away.

My interest in philatelic history has led me to collect published histories of philatelic societies. In one instance when following up on a closed society, I determined that its archives had been left in the hands of the former secretary. This prompted me to write an article entitled “Closed Philatelic Societies” which was published in The London Philatelist (June 2014). On a similar vein, I wrote the presentation, “What will happen to your Philatelic and Unpublished Archives?” for Stockholmia 2019. In both I appealed for people to consider the future of their own and societies’ archives and present or bequeath them to a suitable philatelic organization like the APRL or the Museum of Philatelic History at the RPSL.

On one side, we do not see much research work on philatelic bibliography being published. On the other, recent auctions of literature in 2020 saw some healthy price realizations. Do you think the field of bibliophiles is expanding? Or is it the same few collectors bidding for the items? Further, why is more research not being published, for example in the pages of the PLR, which is the foremost magazine for philatelic bibliography?

There will always be a market for rare books that are only rare because there were so few printed. Accordingly, there do not need to be large numbers of bibliophiles to push the price up, just two or three. The disappointment to me is that those who have significant libraries, and there are quite a number, prefer to write about their stamps and postal history than about their literature. As for the Philatelic Literature Review, at one time, in the 1950s and 60s, it had the field of bibliography more-or-less to itself. Nowadays there are so many specialist societies about with their own periodicals that they are now publishing the bibliographic articles.

On a related note, I have a feeling that more collectors are now willing to spend money on books pertaining to their philatelic interests. Especially if that interest is postal history, where you cannot make do with just a catalogue. What is your opinion?

Most philatelists are stamp collectors or postal historians who specialise in one or several countries or regions. In general, they are willing to spend money on the books about their specialization. They will know and value the rare books missing from their libraries. There are also a small number of philatelists who maintain a sizeable library and they prize the rare works too.

You have had long-standing relationships with many philatelic literature dealers and in particular with HH Sales. Tell us more about your interactions with them.

I was a long-standing customer of Harry Hayes and continued to correspond with him even after he had retired. Naturally, I became a customer of HH Sales from day one. As I was a bit more mobile by then, I took to visiting Stephen and there met Caspar Pottle, his assistant. I always found something of interest, especially bookplates, and I bought anything of historical interest such as society ephemera, which was virtually unsaleable. In fact, I bought it without checking as I was more interested in looking through their new acquisitions than nit-picking about something that they had put aside for me.

Since the 1970s I have dealt with a great many literature dealers, not only in the UK but also in Europe, USA, and even Australia. As time has gone on there is less and less bibliographic and biographical material that I am lacking. In terms of the history of philately, most information is published in journals except for Germany where the output is prodigious, especially by Wolfgang Maassen. It is good to see that some of his works are also being published in English. The most useful dealers over the years have been Leonard Hartmann, with whom I have shared several meals when we have met in London, and Burkhard Schneider. Both dealers have been profiled by you and both know my interests and have sold me important items over the years. Leonard sold me a rare Ricketts index and Burkhard all of the bibliographic works once owned by Bernd Schimmelpfennig. Bernd was a competitor of mine with whom I had corresponded over the years. Over the last decade or two, Cavendish Philatelic Auctions have become a significant source of literature. For some years I was a major buyer of bulk lots for one or two items I wanted, the rest going to the library of the Royal in London.

Sales of literature by major auction houses are sparse. And when they do happen, books are compressed into large lots which means the normal stamp collector who wants a book for his or her reference, especially if based abroad, cannot bid. These lots are mostly picked up by dealers.

The days of Harry Hayes and HH Sales where every book was listed and sold individually are gone. Nowadays lots are made up in boxes to meet the auction house’s minimum price criteria. On the other hand, the boxes are very cheap.

On the subject of auctions, which are some of the most memorable auctions that you participated in? Tell us some anecdotes concerning them.

Naturally, I have participated in hundreds of postal auctions but only attended one “proper” auction. When Leon Norman Williams died, his family sent his working library to Grosvenor Auctions in London.10 Although the brother’s joint library had been sold privately following Maurice Williams’ death, Norman’s working library contained a few things of great interest to me including a collection of bookplates. I attended the viewing day where there were only two of us present. Although I had no idea who he was, I later learned that it was Tomas Bjäringer, then of Paris, now Stockholm (Figure 7).

At the sale itself I had no idea what to do. As I entered, I was handed a table tennis-like bat with a number and was ushered into a room full of chairs. I noticed the philatelist from the previous day’s viewing at the back of the room sitting on one side of a small table so I went over and sat on the other side of the table and we both nodded in recognition. Neither of us moved until the first of “my” lots came up and we both held up our bats, only I held mine up longer and won the lot. A similar scene took place with most of the next dozen or so lots. Then moving out of the bibliographic section I had no interest in the lots. Tomas on the other hand secured quite a number of them. Years later, after we had become firm friends, he told me the story from his point of view. He had recognised me from the viewing when I sat down opposite him. He and I bid on all of the important bibliographic lots and I won them all. By then he didn’t believe that he was going to win anything but I simply stopped bidding and he could get the books he was particularly keen on.

You have been known to be a generous person. For example, you have bought books from certain philatelic literature dealers to keep them going. You have donated your own copies of valuable philatelic works to libraries. What makes you so large hearted?

I had a very good job that paid well. I have never met anyone who got rich dealing in philatelic books. Those dealers who helped me obtain what I was looking for could expect me to provide any help I could to them.

I have written out of the blue to many libraries and from all of these received positive and helpful replies. Many sent whatever I asked for free of charge and often returned the stamps or dollar bill I had enclosed for postage. It seems only right that when I have something of interest to them, I should donate it equally freely.

You had a special relationship with James Negus. Could you tell more?

Jim Negus was the librarian at the National Philatelic Society and also compiled the Stamp Lover index. During this time, he came across my Perfins Abstracts and joined the Perfin Society (formerly the SEPS) to find out more. We met at a Society gathering in London and, being kindred spirits, soon became firm friends. Thereafter, we met very occasionally and corresponded regularly until the end of his life. As he reached the age when he no longer wished to be involved in philately, he gave me boxes of archive material. I also purchased heavily at the sale of his working library.

I met Jim’s brother, Ron, at the Royal where he was the archivist. There, I had been a library volunteer for some years and he convinced me to do some work for the archives – writing up the correspondence. Ron was particularly interested in biographies and we corresponded regularly. Following his sudden death, his wife wrote to me, sending all of his material relating to biographies and some of his books. Apparently, this was in accordance with his wishes. The biographical indexes they compiled now form Appendixes to my work on Biographies.

Who else do you admire in your small field?

There is only one other philatelist who writes regularly on philatelic history and that is Wolfgang Maassen in Germany. He has set up a publishing company, Phil* Creativ Verlag, which supports his writing. He was seriously involved in organised philately in Germany but it was only once he retired that the number of books he wrote reached great proportions. He has also created his own online journal Phila Historica which comes out four times a year since 2013.11 I now publish primarily through this journal. However, even Wolfgang is getting old and beginning to sell off his library.

I have only ever visited three philatelists who had world-class libraries – Hugh McMackin and Stanley Bierman in Los Angeles and Tomas Bjäringer in Paris, who has now moved to Stockholm. Stanley Bierman has now sold his library. One never gets to see Hugh’s library as such since his massive collection is spread across several storage facilities. I have never visited Jonas Hällstrom’s library. At the time of the sale of Soteman’s library12 I visited Vincent Schouberechts in Brussells. He was working for Soteman at that time. His library is relatively small but specialised on his own interests, especially Moens.

In 2018 you moved to a small town in the South of France. What brought about the change in scenery?

My wife, Marion, had always had in mind moving to France when she had retired. When we had both retired, we found a holiday home in rural France and following Brexit, which we both voted against, we decided to move here permanently.

What are your future plans?

When we lived in the UK, I had a large bedroom as a study and two large storage facilities packed with books and other philatelic material that I had not had time to work on. Having decided to move to France I sorted out the storerooms and sent several tons of books and archive materials to the Library at The Royal Philatelic Society. The deal I had with the librarian was that they accepted everything I sent and sold what they already had, the funds going to the library. In spite of this, I still brought three large filing cabinets, five bookcases, and over a hundred large boxes of books and files.

My wife rightly insisted that our first task was to build an extension on the Pool House for me to have as a study (Figure 8). It is only 25 square metres and the roof is rather low so my largest bookcases are within a few inches of the ceiling. However, I had an air conditioning system built in so it is warm in the winter and cool in the summer. Even if I don’t acquire any more material (unlikely), I have years of work entering the backlog I have on my computer. I guess that I have several thousand more pages to go yet!

Acknowledgement: I would like to thank Brian J. Birch for being so erudite and thoughtful in answering my questions. Any feedback can be sent to my email id: abbh@hotmail.com.

APPENDIX – Bibliography of the bound volumes of Brian Birch’s digital works

* Two copies of PT dated 01/2010 were produced by error and to avoid it going waste, the second copy was designated as 5th edition.

A special edition of PPB was presented to Stephen Holder, then of HH Sales, for his help in getting Brian bookplates of philatelists.

The most recent copies shown in the table are still with Birch though they have been designated to go to their respective libraries; they will be sent when he prints out a new edition

Abbreviations of works: PBC – Philatelic Bibliophiles Companion; BPD – Bibliographies of Philatelists and Dealers; CARI – Bibliography of Current-Awareness and Retrospective Indexes; PPB – Philatelic and Postal Bookplates; PLBJB – Bibliography of General Literature and Special Collections in the Philatelic Library of Brian J. Birch; PT – Philatelic Translations Produced by Brian J. Birch; BPP – Bibliography of Philatelic Periodicals.

Abbreviations of libraries: WPL – Western Philatelic Library of Sunnyvale, California; CCNY – Collectors Club of New York; RMPL – Rocky Mountain Philatelic Library of Denver, Colorado; APRL – American Philatelic Research Library of Bellefonte, Pennsylvania; NPS – National Philatelic Society of London; RPSL – The Royal Philatelic Society London; BL – British Library, London; RSPC – The Royal Sydney Philatelic Club; RPSNZ – The Royal Philatelic Society of New Zealand of Wellington; PHILAS – PHILAS Library of Sydney; NWPL – Northwest Philatelic Library of Portland, Oregon; PHF – Philatelic History Foundation of Tuscon, Arizona; PB – Philatelistische Bibliothek of Hamburg

Maassen, Wolfgang, and Vincent Schouberechts. Milestones of the Philatelic Literature of the 19th Century / Les Jalons De La Littérature Philatélique Au XIXe Siécle (Monaco: le Musée des Timbres et des Monnaies de Monaco =Club de Monte-Carlo, 2013).

Harry Hayes (1925-2011) was a well-known British philatelic literature dealer. Operating out of York, He regularly claimed to have the largest stock of philatelic literature in the world. Between 1960 and 1986, he conducted 88 postal and one public auction comprising in all some 65,000 lots. His business was later taken over and operated as HH Sales. The interested reader is directed to my article on Harry Hayes and the index of his auctions which appeared in Philatelic Literature Review (2Q 2018).

The works are available at http://www.globalphilateliclibrary.org/birch.html.

In projects spanning years, Birch has transcribed The Bacon Index (of Edward Denny Bacon) and The Creeke Index (of Anthony Buck Creeke, Jr.). For more details, see Birch, Brian J. “The Bacon Index.” The London Philatelist 119 whole no. 1380 (November 2010): 326-330) and Birch, Brian J. “The Creeke Index – Biographical References.” The London Philatelist 121 whole no. 1398 (September 2012):279-284.

(Bacon, Sir E[dward]. D[enny].). Bibliotheca Lindesiana Vol VII: A Bibliography of the Writings General Special and Periodical Forming the Literature of Philately (Aberdeen: University Press, 1911). Followed by (1) Bacon, Sir E[dward]. D[enny]. Supplement to the Catalogue of the Philatelic Library of The Earl of Crawford, K.T. Published 1911 (London: The Philatelic Literature Society, 1926) and (2) Bacon, Sir E[dward]. D[enny]. Addenda to the “Supplement to the Catalogue of the Philatelic Library of The Earl of Crawford, K.T.” (London: Royal Philatelic Society, 1938).

Butler, A. R[onald]. The History of The Roll of Distinguished Philatelists (London: The British Philatelic Federation Limited, 1990). Three addendums published in 1994, 1999, and 2004.

Birch, Brian J. The Fathers of Philately Inscribed on the Roll of Distinguished Philatelists (London: The Royal Philatelic Society London on behalf of the Roll of Distinguished Philatelists Trust, 2019).

Negus, James. Philatelic Literature: Compilation Techniques and Reference Sources (Limassol, Cyprus: James Bendon, 1991).

I had to look that word up! It means junk or rubbish.

The sale was held on February 9, 2000. Lot nos. 576-796 comprised collection of Cinderellas, etc. and the working library of L. N. Williams.

Phila Historica is an online magazine catering especially to philatelic histories and bibliographies. Issues of the last two years can always be downloaded free of cost and earlier issues can be purchased, either in printed or digital form. See https://philahistorica.de.

Corneille Soeteman is a stamp expert and was a dealer from Brussels operating under the name of ‘La Philatélie Corneille Soeteman.’ His library was sold in three parts in 2001, 2003, and 2004.