This article was first published as “An Inquiry into the First Edition of Fundamentals of Philately.” in Philatelic Literature Review 68 no. 3 (Third Quarter 2019).

Fundamentals of Philately (Fundamentals) by L.N. Williams and M. Williams is one of philately’s most celebrated books. It is, on most occasions, described as the single best introductory didactic book that should be on the bookshelf of every stamp collector.

However, Fundamentals is not a ‘complete’ introductory book. Most such books are known for providing a peek into the various elements of philately such as a brief history of stamps and stamp collecting, stamp production methods, ways to acquire stamps and build a collection, stamp collecting accessories, famous stamps, and notable stamp collectors of the past. On the other hand, Fundamentals is, or rather turned out to be, almost exclusively, an analysis of stamp production via its discourses on stamp paper, watermarks, design, printing methods, inks and color, gum, and separation types.

While most reviewers have traditionally fawned upon it and placed it on a pedestal, Fundamentals is undoubtedly a very difficult read for the general reader.1 Supposed to supply “basic knowledge”, it turned out to be too detailed and technical, almost like a doctoral-thesis; for example, the chapters on various printing methods occupy 342 pages! Hence, notwithstanding the repute of its writers and consequently the repute it made for itself, the book has come in for some criticism over the years.2

This article is on the five Sections that preceded the 1971 edition as well as the four printings of the 1971 edition itself.

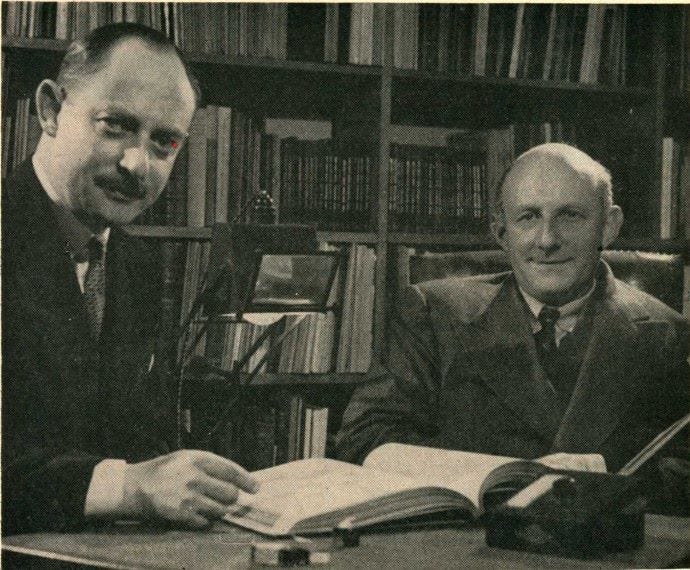

The Williams Brothers

Leon Norman Williams and Maurice Williams (Figure 1) need no introduction to the vast majority of readers. They were, along with Fred. J. Melville, philately’s most prolific writers. Born in London in 1914 and 1905 respectively, Norman3 was a barrister-at-law while Maurice, who was incapacitated being a victim of polio at school, was a professional journalist (Lidman 1954, Birch 2018).

The brothers started their philatelic writing in 1934 and wrote more than 30 handbooks apart from countless articles. They held editorial positions at various stamp journals like The Stamp Lover (1940-1964), The British Philatelist (1940-1954), and The Cinderella Philatelist (1961-1998). Further they owned a philately library which was reckoned to be the biggest private one in Great Britain. While Maurice died on June 15, 1976, Norman continued writing and published the revised edition of Fundamentals in 19904 and the two-part update to their earlier works on rare stamps, Encyclopaedia of Rare and Famous Stamps, in 1993 and 1997. Norman died on April 9, 1999.

Beginnings of Fundamentals

The foundation for the publication of Fundamentals was laid by David Lidman,5 the then editor of The American Philatelist, who requested6 the brothers7 to supply for the journal “a survey of the basic knowledge requisite to serve as a groundwork of philately” (Williams and Williams 1958).

The first installment of the work was published in the April 1954 issue of the journal. Its objectives are clearly laid in the authors’ introduction. It would aim to set out objectively,

the why and how of stamp collecting, what to look for, what to avoid, and the general problems, or some of them, which the collector is likely to encounter in his philatelic life.

The authors hoped to deal with,

…accessories such as albums, hinges, catalogues, and general literature, fields of collecting such as general, restricted and specialized, subjects for study such as printing methods, paper, separations…and, of course the stamps themselves in their categories.

The aim of Fundamentals was to be of assistance to adult “beginners” (Williams and Williams 1954).

Four years later, in the preface to Section 1, the plan of the work is stated viz: (1) Introduction, (2) Production, (3) Classification of Stamps, (4) Collecting and Study Techniques, (5) Social Philately, and (6) Index (Williams and Williams 1958).

In 1990, Norman clarified that it who was he who was the true author of Fundamentals having written each and every word of it as Maurice’s philatelic interests lay in other directions. However, in keeping with the fraternal writing policy that the brothers had adopted since the very beginning, the work was published in their joint names (Williams 1990). Another early evidence of this assertion can be found is in the preface to Section 5 wherein Norman accepts the blame for the delay in its publication8 (Williams and Williams 1968).

Plan unfinished

Serialization of Fundamentals continued for more than nine years until June 1963. The work had, by the last issue, covered (1) and (2) and ended with the words “Next: Classification of Stamps” i.e. an intent to start with (3) (Figure 2).

However, no further installments came through. In their preface to Sections 3 and 4 published in 1964 and 1965 respectively, the authors have dropped the six-point plan mentioned in Sections 1 and 2. They do seem to give some bit of hope to the reader when they say, “ten years and more since its inception the work is far from completion in the plan originally outlined” (Williams and Williams 1964, 1965) perhaps implying the possibility of keeping the series going.

However, the preface to Section 5 does not even contain this line (Williams and Williams 1968). It is now clear that after more than 15 years writing Fundamentals,9 the authors have decided to discontinue working on it any further.10

In their preface to the 1971 bound edition, the authors justify this saying, “a limit had, perforce, to be set.” They also acknowledge that while the fundamentals of philatelic knowledge are not bound by only an understanding of its history and the processes of stamp production (i.e. the topics covered by their work), such understanding is essential to anyone wanting to be known as a philatelist (implying that even incomplete, the work will be of much value to its readers) (Williams and Williams 1971).

Bibliography of the Five Sections and Appendix

The authors quoted regularly in their prefaces that one of the principles they would be guided by was to pay special regard to pictorial representations since, quoting W. Dudley Atlee from the December 1869 issue of The Philatelist, “…nothing is so satisfactory as ocular demonstration”. I aim to follow in their illustrious footsteps and include many photographs as is required!

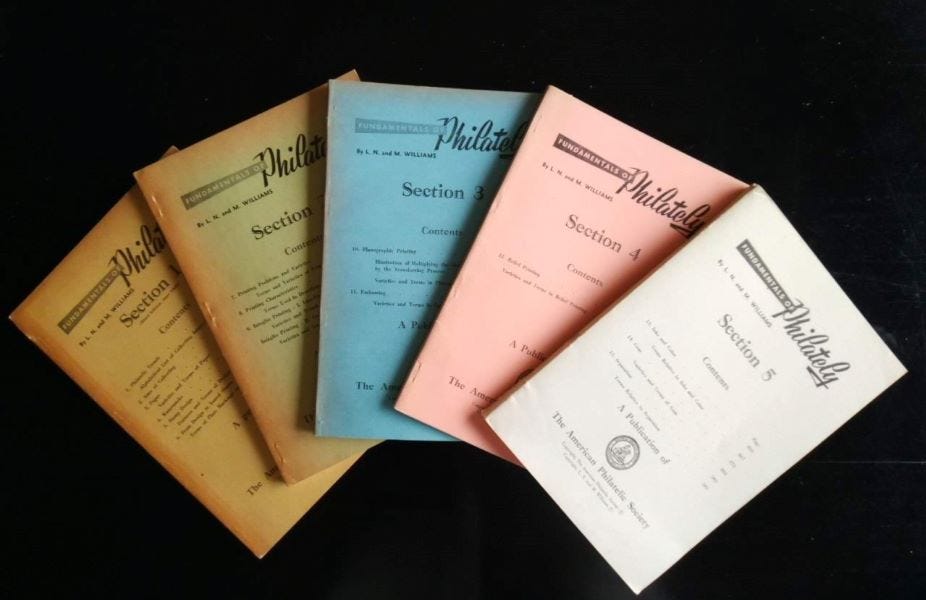

Between 1954, when the first installment of the work was published in The American Philatelist, and 1971, when it appeared as a single book, five Sections of Fundamentals came out (Figure 3). It had always been the intent of the authors that the work would someday be presented in a book form. Until then these individual Sections intended to cover those subjects already completed in the journal and thereby make the work available earlier than would have been otherwise possible.

The Sections were not just re-printings from the journal but incorporated additions and revisions. This is one of the reasons for the usual delay in the publication of the various Sections after their subject matter had appeared in the journal. Section 5 was especially much delayed for more than five years when it was finally published in 1968.

The Sections were bound in card covers of different colors; being yellow-ocher, pale green, pale blue, pink, and light-grey from Section 1 to 5 respectively. Further, the first four Sections were staple bound while the last was perfect bound. Unfortunately, it is not known how many copies of each were printed.11

Apart from the five Sections, an undated pamphlet exists containing an appendix of corrigenda and addenda and an index compiled by James Negus.

The accompanying table summarizes each of the Sections and the appendix.

a Preface dated “May 1958”. Two further editions were published, a second in February 1960 and a third in June 1963. I have copies of the first and third both of which have the same 1958 preface and whose contents seem to be similar.

b Preface dated “April 1960”

c Preface dated “London 1964”

d Preface dated “London 1965”

e Preface dated “London, March, 1968”

f It is not known when this was published but it must have been after the publication of Section 5 in 1968 and before it was bound up along with the other Sections into a single book in 1971.

Bibliography of the Four Printings of the 1971 Edition

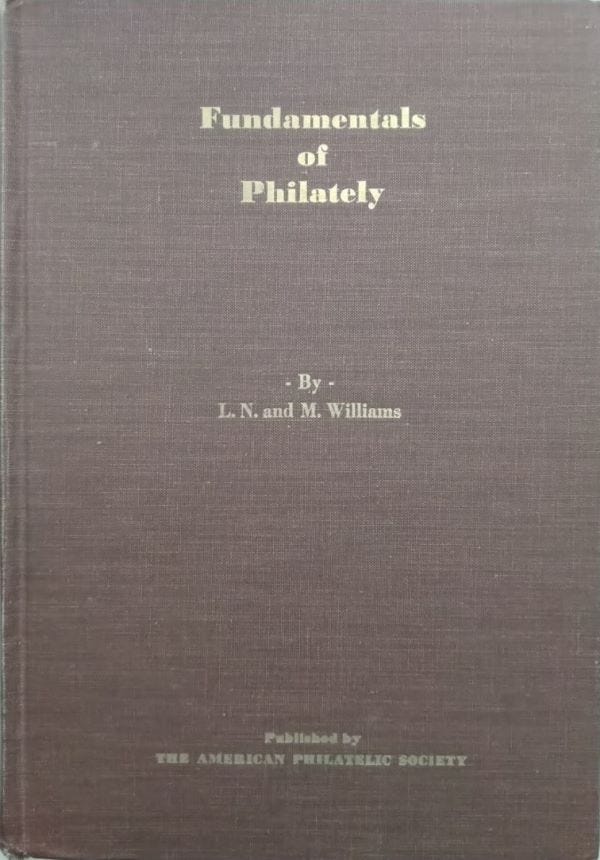

Sometime in 2018, I noticed that the 1971 edition was available hardbound in both reddish-brown (Figure 4) as well as light-grey cloth. Wondering why and what the differences were, I inquired with some philatelic literature dealers, who would have handled the work extensively, but did not get a satisfactory explanation.

I later bought both the colors and found the words “Unabridged Edition” on the copyright page of the brown and “Unabridged Edition. Fourth Printing” on the grey. This led to further questions including about the second and third printings.

It was in April 2019 that I stumbled upon the explanation to the “confusing printing history” of Fundamentals in Negus (1991, 234) who had sought the same clarification from Norman.

First Printing

The first printing (true first edition) was of 1,000 copies. It contains a new preface dated “London, 1971” but does not have a contents page for the entire work. The five individual Sections, sans their card covers but including their titles and prefaces (which were printed on the two different sides of a single sheet of paper), have been bound up together. After its 629 printed pages (not including the five section titles and prefaces), follows 30 pages of corrigenda and addenda and a detailed index.

The copyright page has “Unabridged Edition” (Figure 5) but no words about it being the first printing. The printer is ‘The J. W. Stowell Printing Company’ of Federalsburg, Maryland (Figure 6). While Negus (1991) does not cover the color of the bindings of the various printings, the first printing (as well as the next two) were bound up in reddish-brown cloth with gold stamping on the front covers and spine; no dust jacket was issued.

Second and Third Printings

The first printing sold out within a few weeks. The book has been hot-metal typeset but the type was unaccountably melted down after publication. Hence photo-reproduced plates were issued to make the second printing of around 1,000 copies.

Of these 1,000 copies, 500 were issued as “Second Printing” and by masking the reverse title page, the balance copies were labelled “Third Printing”; it is not known why. Hence the copyright page has the words “Unabridged Edition” followed by “Second Printing” (Figure 7) or “Third Printing” (Figure 8), as the case may be, on the next following line before the other copyright details.

Note that printings made after the first one omits the repetitive titles and prefaces (Figure 9).

Further, the printer was changed to ‘The Maple Press Company’ for the Second, Third, and Fourth Printings (Figure 10)

Fourth Printing

The plates of the second and third printing were then dumped. A fourth printing (actually the third) was photo-reproduced from the previous printing. This printing was bound in light-grey cloth (Figure 11).

The copyright page has the words “Unabridged Edition” followed by “Fourth Printing” (Figure 12) on the next following line before the other copyright details. Unfortunately, its print run is not known.

Conclusion

The Williams set out to produce an all-encompassing work intended to convey basic knowledge of philately to the adult-beginner. After spending 15 years in perfecting12 just the one subject of stamp production methods, they gave up on the project. In hindsight less detailing would have enabled full coverage of all or most of the planned topics and made Fundamentals a truly introductory book.

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Scott Tiffney, Librarian of the American Philatelic Research Library for providing me with extracts from The American Philatelist as also Burkhard Schneider for scans of the third printing. I am also grateful to Bill Hagen, Leonard Hartmann, and Casper Pottle for their valuable inputs. Any feedback or information can be shared on my email id: abbh@hotmail.com.

Bibliography

Birch, Brian J. 2018. Biographies of Philatelists and Dealers. Montignac Toupinerie, France: The Author. http://www.globalphilateliclibrary.org/birch/BiographiesOfPhilatelistsDealers.pdf

[Lidman, David]. 1954. “About L.N. and M. Williams.” The American Philatelist. April 1954: 502-504.

Negus, James. 1991. Philatelic Literature: Compilation Techniques and Reference Sources. Limassol: James Bendon.

[Strange, Arnold M.]. 1969. “Literature”. The London Philatelist. Vol. 75 No. 887 (November 1966): 223

[Strange, Arnold M.]. 1969. “Literature”. The London Philatelist. Vol. 78 No. 917 (May 1969): 123

Williams, L.N. 1990. Fundamentals of Philately. State College, Pennsylvania: The American Philatelic Society.

Williams, L.N., and M. Williams. 1958. Fundamentals of Philately: Section 1. State College, Pennsylvania: The American Philatelic Society. 3rd edition published June 1963.

———. 1960. Fundamentals of Philately: Section 2. State College, Pennsylvania: The American Philatelic Society.

———. 1964. Fundamentals of Philately: Section 3. State College, Pennsylvania: The American Philatelic Society.

———. 1965. Fundamentals of Philately: Section 4. State College, Pennsylvania: The American Philatelic Society.

———. 1968. Fundamentals of Philately: Section 5. State College, Pennsylvania: The American Philatelic Society.

———. 1971. Fundamentals of Philately. State College, Pennsylvania: The American Philatelic Society.

It is quite strange why it turned out so. The many other books of the Williams brothers, including the ones that they wrote for children, are fast easy reads.

See, for example, Strange (1966) who comments in his review of Section 3, “This is undoubtedly a work by the pundits for the pundits but the average collector may find that parts of it contain more detail than he cares to digest. It is therefore conceivable that the authors have failed in their intention to cater for adult 'beginners'.”

Strange (1969) in his review of Section 5 repeats, “…we are under the impression that its profundity may at times be too great for even the 'adult beginner' for whom the authors aim to cater.”

Recently in 2016, the well-known US dealer, John Apfelbaum’s blog on the book says that Fundamentals is fundamentally unreadable, boring, and turgid, and its details detract from the very experience that it was intended to enhance. See https://www.apfelbauminc.com/blog/post/fundamentals-of-philately. Accessed 24 Jun 2019.

One of the literature experts who I sent my initial draft to in 2019 commented that he did not have a high opinion of Apfelbaum, the firm. However I did not remove this reference since I felt that, nothwithstanding their reputation (on which I have no opinion), the blog makes an important point with which I partly agree.

L. N. Williams was known as Norman and not Leon (Williams 1990, xiii).

The revised edition was published in Norman’s name alone but it was dedicated to Maurice.

David Louis Lidman (1905-1982) was one of America’s greatest philatelic writers and editors. He wrote stamp columns for the New York Times from 1948 to 1972. He edited The American Philatelist from 1951 to 1960 as well as many other publications. He also wrote many books especially popular ones on stamp collecting. For a detailed overview see https://classic.stamps.org/HOF-1980. Accessed 24 Jun 2019.

The words “perhaps lightheartedly” was inserted before “requested” starting from the preface to Section 4 (Williams and Williams 1965). By this time, it must have been quite apparent to the authors that the work they wished to fashion would be necessarily enormous and possibly would not see completion.

The Williams brothers were already famous and prolific at this time. This is evident by the three-page introduction to the authors that Lidman (1954) wrote to the first instalment.

The preface reads, “That this Section has not appeared before now must, in the first instance, be laid at the door of one who, as a barrister-at-law, is not unused to being in two places at once, but has not yet discovered the secrets of writing more than one thing at the same instant, and of finding more than 24 hours in 24.”

The authors would have commenced writing Fundamentals possibly a year or two before the first instalment of April 1954. Further, it can be said to have been completed with the publication of Section 5 in March 1968. Hence the number of 15 years; this is also collaborated by Norman in the revised edition (Williams 1990, x).

Norman (1990) mentions that the revised edition was under preparation for eight years. It is not clear why he did not cover the earlier planned but undelivered topics in this edition. Since Norman was a perfectionist, undertaking any new work requiring perfection would require a herculean effort on his part, which may not have been possible for him to undertake.

Hagan (Bill Hagan, 2019, Email message to author) is of the opinion that there may have been a few presentation copies produced with deluxe covers and inscriptions. In case any reader has more information on the same, please contact me with details.

Norman’s efforts were always to record fact and avoid fiction (Williams 1990) and it cannot be argued that he did not succeed. Fundamentals is as perfect a technical book as can be.