The Bibliophile of Schwalmtal-Waldniel: Wolfgang Maassen

An interview with the prolific German philatelic historian

It seems to me that more people subscribe to and read me on this Substack channel than elsewhere - whether it be my own website (philaliterature.com) or printed journals. Hence I am going to put up manuscripts of some of my articles which have been published in print here. Starting with an interview with Wolfgang Maassen, philatelic historian par excellence.

First published as “The Bibliophile of Schwalmtal-Waldniel: Wolfgang Maassen.” Philatelic Literature Review 70 no. 3 (Third Quarter 2021). It won the American Philatelic Research Library’s 2022 Thomas F. Allen Award for the best article to appear in the Philatelic Literature Review the previous year). Later translated into German and republished (with many more photographs) as “Ein Interview von Abhishek Bhuwalka, Indien, mit Wolfgang Maassen, Schwalmtal.” Phila Historica no. 4 (December 2021)

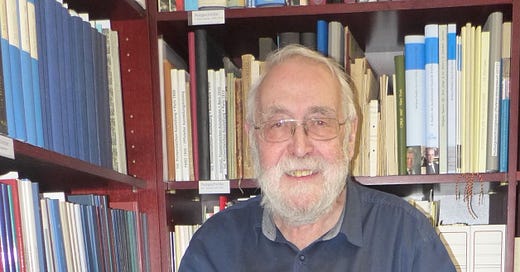

Philatelic researcher, writer, editor, publisher and organizer. All these and more is the indefatigable man from Schwalmtal-Waldniel in Germany – Antonius Peter Wolfgang Maassen (Figure 1). If Brian Birch, my last interviewee, is the “greatest philatelic bibliographer of all time,” Maassen (or Maaßen in German) is, in my opinion, the greatest philatelic historian of all time. With a writing career beginning in the mid-1970s writing about modern ‘automatic’ stamps, moving on to the stamps of Brazil in the late 1970s to early 1980s, and then to philatelic history and bibliography, Maassen’s published output has been humongous. Apart from writing articles and books, editing numerous journals, and contributing to organized philately, he has a publishing company called Phil*Creativ GmBH1 whose antecedents date back to 1986.

Why philatelic history of all subjects? When asked, Maassen says that history has always interested him. He approvingly quotes one of his former professors who said, "History is an immersion in another world, often unknown to us, from which one returns enriched." Further he believes that one who does not know his past has no future (this statement reminds me of the famous words of the philosopher and writer, George Santayana, “Those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”) Many answers are already available in old books and journals and documentary archives; without digging into the past, future researchers cannot pen better manuals.

I met Maassen a couple of years back in Stockholm and found him to be a very modest and down-to-earth man. However, make no mistake; behind his simplicity is a steely will which enables him to spend 12 hours a day, seven days a week, researching and writing about philatelic collectors, dealers, forgers (a most charming subset of philatelic personalities!); institutions; literature, and more. I was very inspired with the way he comes across in this interview going about his business; in fact, I would say that I had goosebumps by the time I came close to the end!

Maassen is well-known in Germany as well as in the uber philatelic world. I hope that through this interview he will be as widely recognized in the English-speaking community for all his immense philatelic contributions.

Wolfgang, please tell me about yourself?

I was born on January 25, 1949, in Erkelenz, in a small town of about 10,000 inhabitants, in the Rhineland in West Germany. My father was an engineer and my mother a housewife. About five years later we moved to Euskirchen, where my father took on a managerial position in a mechanical engineering works. We stayed there for about three years until my father improved his career and later became the manager of a mechanical engineering company in Cologne. That was one of those typical post-war careers: from small beginnings to the top position. My father was frequently absent and my mother often ill for long periods of time; since I was an only child, I wished for change and a boarding school seemed to be the suitable place to find age-appropriate friends.

I had attended primary school until the age of ten, when I went to this boarding school in Schiefbahn and attended Gymnasium (high school) for six years. Then I moved to Cologne and completed the last three years of the upper school (college) of the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Gymnasium and finished my school education with the Abitur (A-levels).

I was a mediocre student, but I had special preferences for chemistry and philosophy and was very good at them. My father encouraged me to take up chemistry because he saw a future for me in his company. So, I studied chemistry for a few terms from 1968. But I found out that it was not the right thing for me after all and I switched to humanities in 1970. It was at this time that I met my future wife, Claudia. Our “love story” began. We married in 1973 and had two children – Maike, born in 1978, and Michael in 1980 (Figure 2).

In 1974 I finished my main studies (education science, theology, philosophy) with a first exam2 and then many things happened differently from how they were actually planned.

You were a professor at a college, were you not? How and why did you decide to take on a teaching profession?

Originally, I had planned a university career. I wanted to do a doctorate and post-doctoral thesis. I had a professor with whom I had worked as a student in the department of educational science. I was one of his better students and he was willing to promote me and even held out the prospect of a professorship in Vienna at that time. He, however, advised me to do a teacher traineeship for the Gymnasium in parallel beforehand and wanted to get me the training position in Bonn (we lived near Bonn at the time, the federal capital).3

However, I was transferred to Krefeld, Viersen district. This meant that the plan of a simultaneous assistant position with my professor and a parallel traineeship was out of the question; I had to choose one. Since Claudia also wanted to become a teacher at that time and was aiming for the traineeship, we both went to Viersen, about 100 km from Bonn. My university days were over.

I became a college teacher and found that I liked this job. Educational science at the Gymnasium was a new subject at that time and one could build new structures from scratch, develop curricula, and design completely new teaching systems. So, in 1978 I became one of the youngest trainee teachers of educational science in North Rhine-Westphalia. I had only had two years’ experience myself! We first settled in Viersen. Then around 1979 we moved to a small village, Schwalmtal-Waldniel, and it had a college where I could teach. It was an ideal place for our children, because it had everything you needed. And we had a new home of our own.

Almost everyone involved in philately that I know of grew up collecting colorful stamps! How did you get into the hobby?

It all started with the usual small all-world collection as a child, followed by a long break, until I accidentally rediscovered stamps as a student – together with Claudia. I was sitting outside Bonn University during a lunch break. There was a small stamp shop nearby. A disappointed fellow student settled down on a bench next to me and cursed the low price the dealer was willing to pay him for his albums of stamps. I took a look and was surprised. The dealer was even unwilling to give him DM 100 for the three albums full of covers from the first years of the Federal Republic. Even though I did not have the then-current catalog prices in my head, I knew that neatly used covers with welfare sets from 1949-1953 were rare and expensive; as a child I had never been able to afford such things. I gave the student the 100 marks he wanted. At home I discovered (I had not seen this before!) that under each cover there was not one, but often several envelopes, sometimes up to five. All FDCs, which were expensive and in demand at the time, were from the early issues of the Federal Republic.

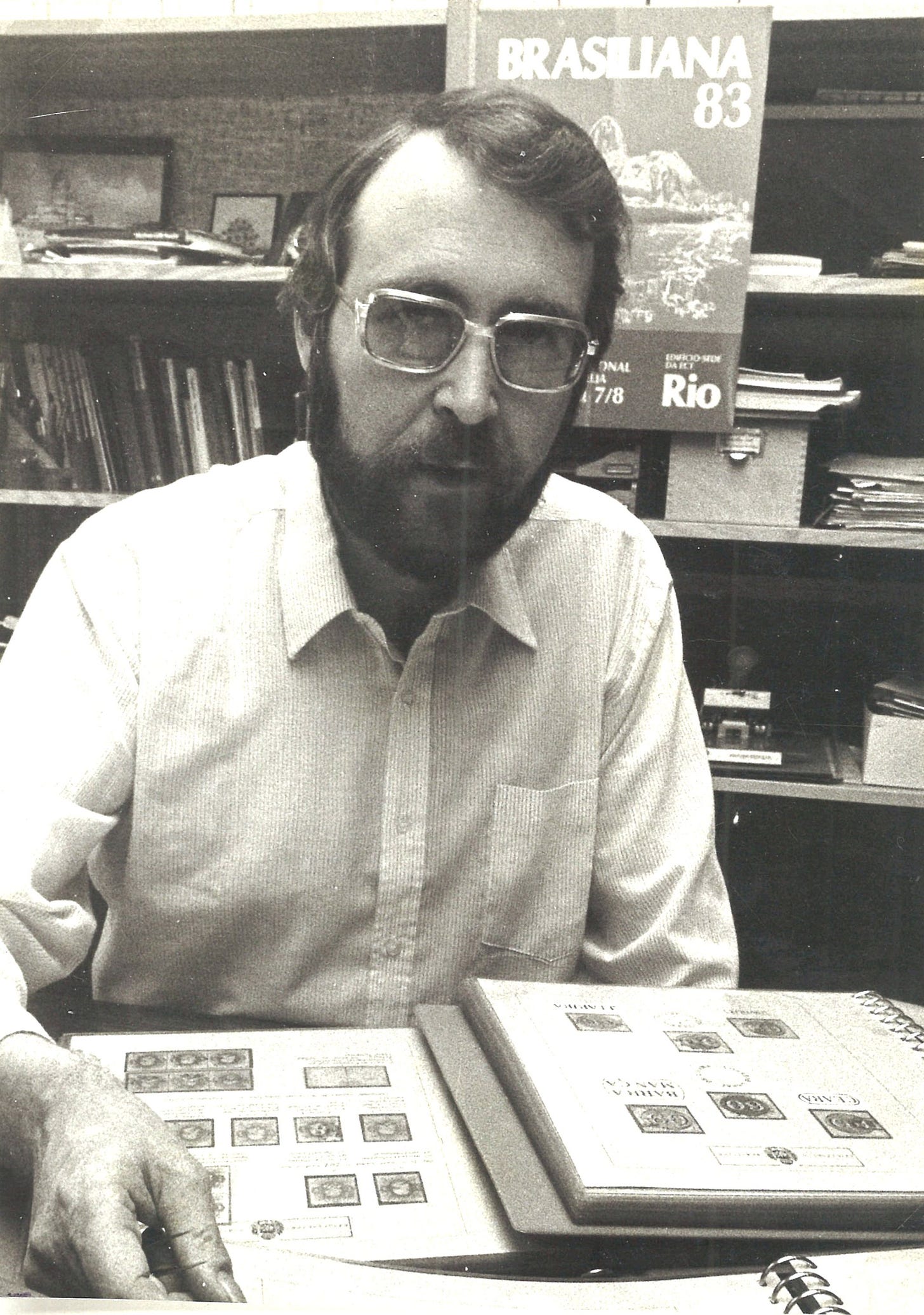

So, Claudia and I started collecting together. We bought kiloware, washed the stamps off the paper together, attended exchange days together, and dealt a little on the side to supplement our student income, which was quite modest at the time. When, as young teachers, we had earned a lot of money and what everyone collected was not enough for me, I had the idea of collecting something exotic that not many did. One of my aunts, my father's sister, had a kind of student aid organization for Brazilian students who were studying theology in Rome. She always organized students’ jobs in German companies for them during the summer break. So, I came into contact with a lot of Brazilians and spent a few weeks in Rome at the Collegio Pio Brasileiro. This is how my enthusiasm for Brazil, for the country and its people, and for Brazilian philately grew (Figure 3).

A chance meeting with Karlheinz Wittig in 1978, who had founded a Brazil working group at that time, encouraged me to take this path. He is more than 20 years older than me and fortunately still alive today. Between the two of us, a good friendship and cooperation developed. He taught me everything he knew and I became a classic Brazil specialist, even writing a four-volume Einführung in die Brasilien-Philatelie [Introduction to Brazilian Philately] between 1980-83. I collected and specialized in everything related to Brazil, from old to new, all related subjects and specialties.

Over the years, I also discovered the charm of other Central and South American countries, the first issues of which I also collected, such as Mexico, Peru, Colombia, Argentina, Chile etc. But of course, I also got to know my limits, especially when bank interest rates rose enormously in the 1980s. We had bought our own house in 1979. Only six years later, the financing ran out. Suddenly the interest rate was 11% instead of 6%, which was a big problem for us, especially since we now had children. With a heavy heart, I decided to sell the collections, because all I was missing in Brazil were the rarities (larger multiples, covers with rare postmarks, etc.).

I found new fields of activity, first in modern philately, where there were the so-called “automatic stamps”4 at that time, which were produced in stamp printers. I wrote several books and catalogs on this subject. When this area became too speculative for me – profiteering was always abhorrent to me – I decided to focus on literature and a few years later on philatelic history. Of course, I have also built up other small collections on more thematic aspects (such as German Unification, Europe in Transition and many more). But for the last 25 years the focus has clearly been on philatelic history.

Have you exhibited your collections of stamps and/or postal history? Tell us more about it.

Between 1980 and 1985, I showed my collections of classic Brazil and South America several times at German exhibitions with quite good success. In 1983, I exhibited my Brazil collection for the first time at BRASILIANA in Rio de Janeiro and received a Vermeil for it; at that time there was no Large Vermeil. This was the highest award for a Brazil exhibit by a foreigner. Of course, exhibits by Brazilians themselves were much better, for example that of Reinhold Koester. And Koester made it clear to me that I would still have to invest six or perhaps even seven-figure sums in order to receive Large Gold or higher one day. I did not have the money, nor did this appeal to me. At that time, I stopped entering competitive exhibitions.

Since then, I have only exhibited collections by invitation i.e., non-competitively. One exception was NAPOSTA 2020 in Haldensleben, which I wanted to support and therefore showed two smaller new philatelic collections there. One was awarded a Gold, the other a Vermeil medal. Another exception: I have been exhibiting my own literature nationally and internationally for about 20 years. I really cannot complain about recognition and success.

I was astonished when you mentioned to me that you have penned some 5,000 long and short philatelic pieces. How did you get into philatelic journalism?

This came about by chance in the 1970s. I always liked writing and so I took over two columns in a magazine that was very popular in Germany at the time - Der Sammlerdienst.5 Other magazines such as Deutsche Briefmarken-Zeitung (DBZ) came along.6

In the 1980s my writing developed more and more and in 1988, the Bund Deutscher Philatelisten (BDPh) or German Federation of Philatelists7 appointed me editor-in-chief of their society magazine philatelie, which I then led until the end of 2016. Claudia and I managed the editorial work and later the production of the magazine together as a “mixed double;” like in tennis! We turned this magazine, originally published six times a year, into a monthly journal with a much larger scope than ever before. Claudia took care of the advertising and typesetting as well as the layout and I was the editor. I also wrote several articles myself in almost every issue, about philately but also about God and the world! In addition, I regularly wrote for other papers and also for catalogs of all kinds. And in the last 30 to 40 years, hundreds and thousands of articles have accumulated.8

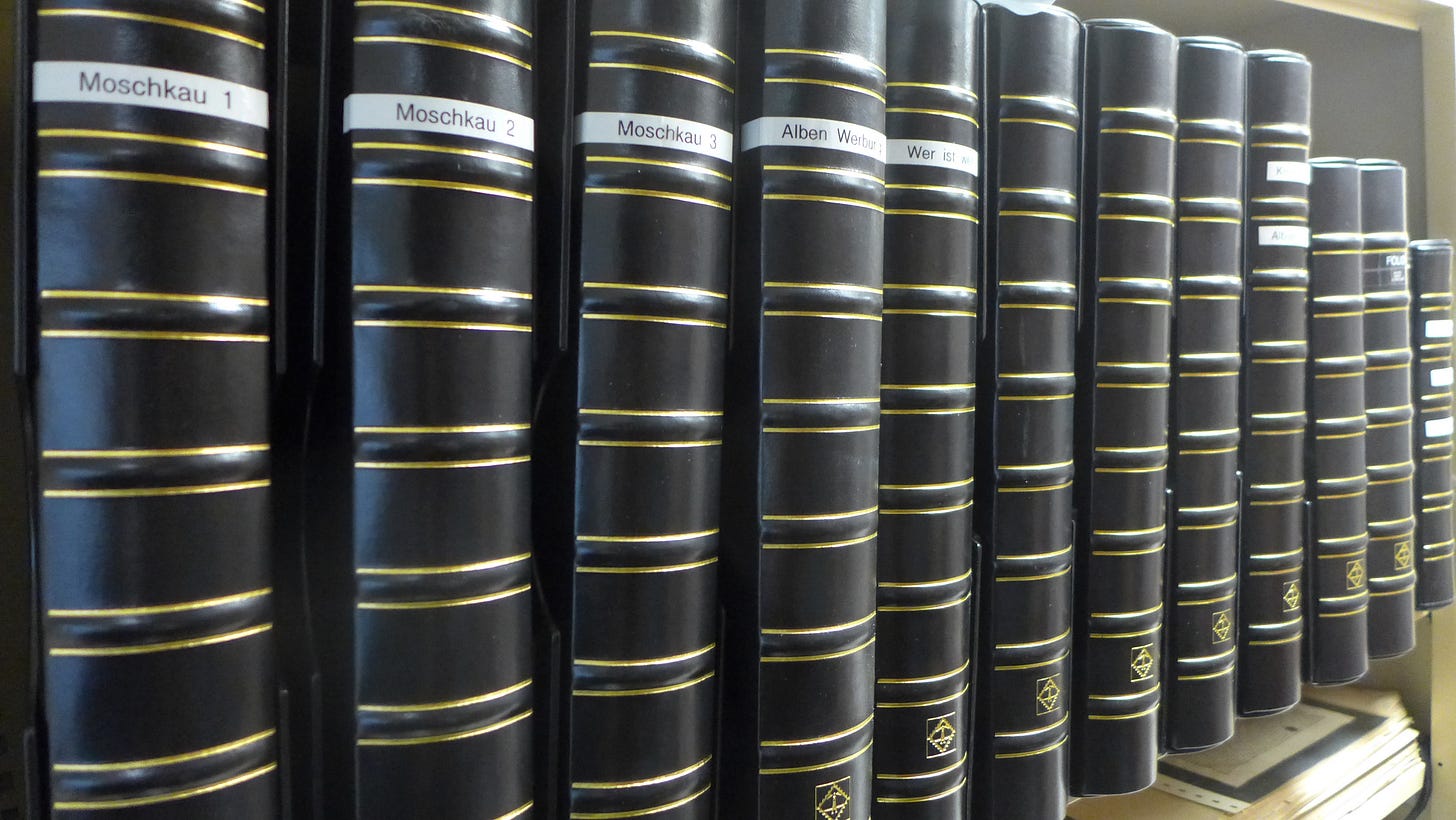

One of your long-term book projects going back to the late 1990s is Wer ist Wer in der Philatelie? [Who is Who in Philately?]. Four volumes of this have been published to date covering the names of philatelists from A to R. How did you decide to start this series?

In my earlier studies, I also took several terms of personality psychology. People have always fascinated me: their history, their stories. In 1993 I got to know Prof. Carlrichard Brühl personally at the then-BRASILIANA in Rio de Janeiro. I knew his monumental two-volume Geschichte der Philatelie [History of Philately]9 and appreciated it very much. He, and almost at the same time, another well-known German philatelic historian, Norbert Röhm, aroused my interest in the personalities who had played a prominent role in the history of philately. In 1997, Röhm approached me and said that I should once again take up the idea of a “Who’s Who in Philately?” for which there had been German forerunners 50 or more years earlier. I found this interesting.

He also cooperated with me and so the first edition of a “Who’s Who...?” was produced in 1999. In 2005/2008 a second edition was published, but only digitally on the BDPh website. In the meantime, like a man possessed, I had collected all the journals I could acquire in languages I could understand. I analyzed them and increasingly added new information, so that in 2011 it seemed expedient to me to produce a third edition, but this time in print, again, and in several parts. Volume 1 (letters A-D) appeared in 2011, Volume 2 (E-H) in 2017, Volume 3 (I-L) in 2019 and Volume 4 (M-R) a few weeks ago. I hope to publish the last volume up to the letter “Z” in two to three years.

While in 1999 there were almost 1,000 philatelists’ portraits that I was able to include, mostly short ones, there will now be perhaps 5,000 or more and often more extensive ones. Some biographies are three, four, or more pages long. This has probably never been done before in this way and to this extent, although special works, such as those on the Fathers of Philately,10 have also taken up comparable approaches but only for a manageable number of personalities. I work very closely with my friend Brian Birch and many others.

However, only biographies of philatelists are included who have or had a connection to Germany in a more or less direct way. To take this approach worldwide would have been impossible for me. And no one would have bought a 20 or 30 volume work!

I have to say that my love affair with philatelic literature started on reading your 2013 co-authored book, Milestones of the Philatelic Literature of the 19th Century. It was so lavishly produced and I just could not take my eye off the beautiful photographs. Not to forget that the writing style was racy and made a supposedly dry topic so much more interesting. What are your recollections about that book?

The idea for this book11 and for a special literature exhibition in Monaco in 2013 came about two years earlier. It is mainly thanks to my good friend Vincent Schouberechts who put the idea into the ear of the President of the Club de Monte-Carlo, Patrick Maselis, that an exhibition of old and rare literary rarities could be organized. Patrick liked the idea but wanted, as is tradition in Monaco, a suitable reference book to go with it. So, the ball was in our court. I developed a first concept, which we refined more and more. I also began to research and write the book, while Vincent made contact with all the bibliophile collectors and experts he knew; we complemented each other brilliantly. We visited Raffaele Diena's library in Rome together for several days and other places where we found literary treasures – not only from the Royal Philatelic Society London, but also the Leipzig National Library and many others. So, our stock of knowledge, photographs, and other artefacts grew, and not just because we both collected literary treasures ourselves.

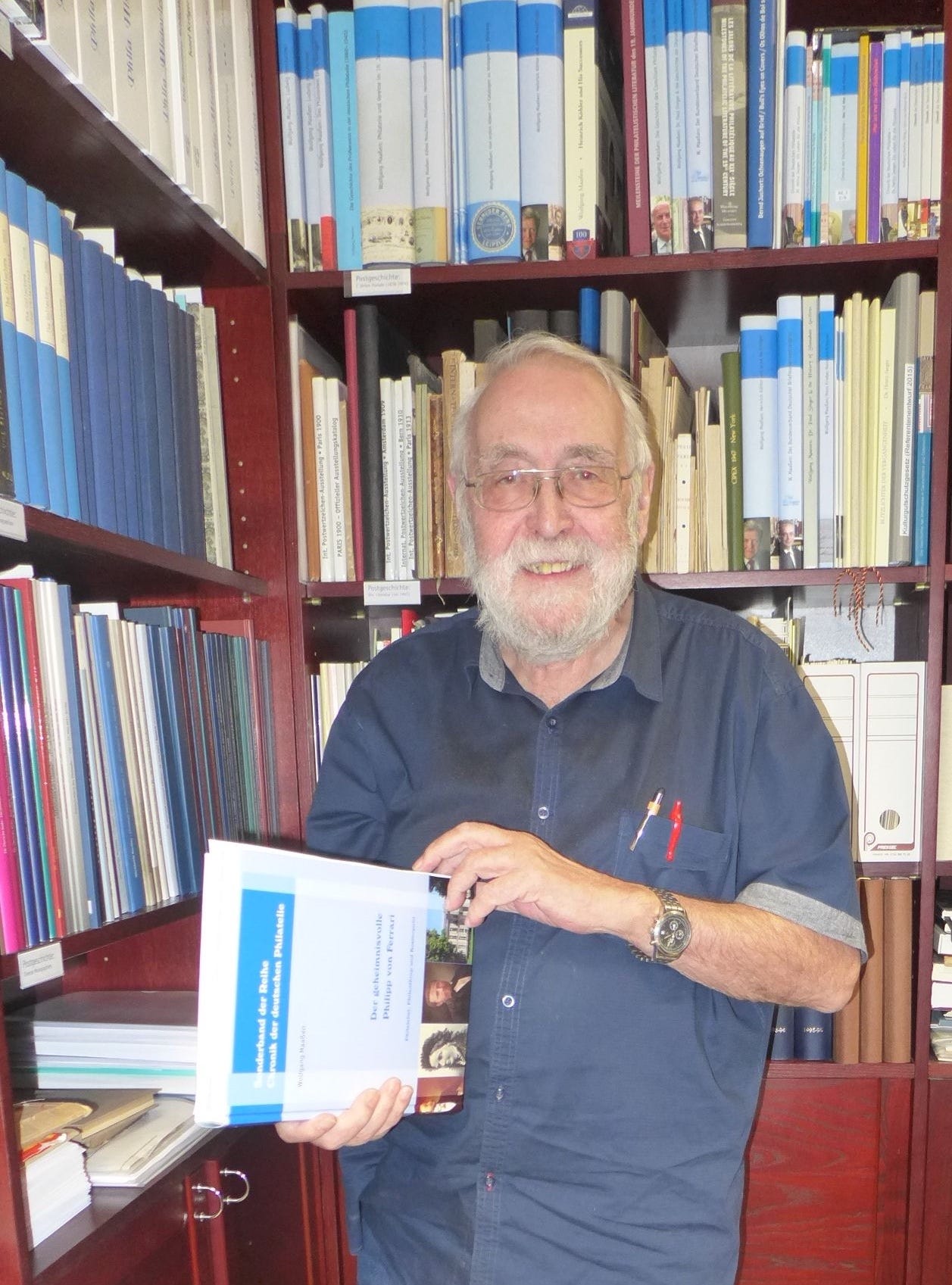

We would have liked to work with Dr. Manfred Amrhein, but unfortunately, he was no longer available to us. But his multi-volume work12 was an excellent source that offered us countless references that we could research further and find what we were looking for. The rest was then done by an excellent graphic designer who turned our manuscripts and illustrations into a really beautiful book that I still love today; literature can be so beautiful! In addition, the countless conversations, the evening discussions in Monte-Carlo and getting to know other renowned literary specialists are unforgettable experiences for me that I always remember with pleasure (Figure 4).

You have written many books on philatelic personalities and houses. Many were naturally on German names like Alfred Moschkau, Heinrich Köhler, Dr. Heinz Jaeger, and Reinhard Krippner. However, recently you have published some on non-German names like Philipp de Ferrary (2017), Dr. Paul Singer & the infamous Shanahan auctions (2019), and the forger Peter Winter (2021). The amount of research you put into them is huge! How do you manage to get so much new information?

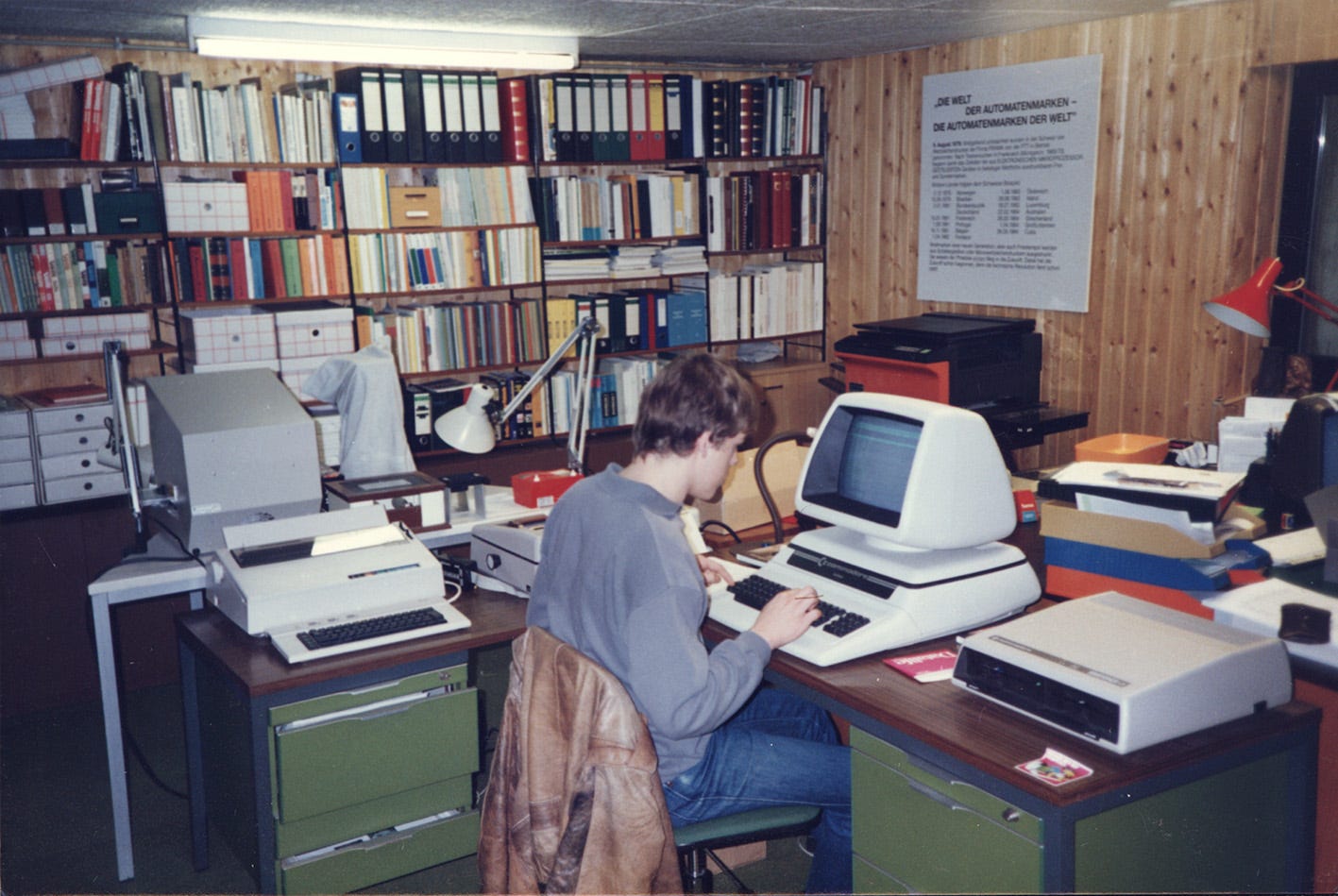

I am a workaholic: work, writing, researching, collecting, archiving is my life. Seven days a week, 12 or more hours a day. I have done this for 30 years and have accumulated treasures, resources that I could put to good use for my journalistic work (paper and photo archives), but also for my own books (Figure 5). People, as I have already said, have always interested me. And I discovered in my work on “Who’s Who...?” that there were biographies that were so contradictory, so different, that I became curious to separate legend from truth. This was especially the case with Alfred Moschkau, the German pioneer philatelist, but also with Philipp von Ferrary, the “stamp king.”

But some things also came about by chance, be it through an anniversary or at the suggestion of a third party. Writing about Shanahan and Dr. Paul Singer13 came about because I acquired a very extensive amount of documentation from the David Feldman auction house that enabled me to do so. It was similar with Moschkau. I was able to acquire the extensive and valuable archive collection of Renate and Christian Springer and combine it with my existing holdings, so that today it is probably the largest museum documentation that exists on this German pioneer philatelist. Ferrary had already attracted me as a youngster. What a person, what a subject! Ten or more years ago, the Hamburg auction house Schwanke offered the estate of Pierre Mahé. I managed to acquire a good part that was directly related to Ferrari; Mahé had been the curator of his collection. The other part was auctioned off from under my nose; later I got to know that it was by Eduardo Escalada from Madrid. I have counted him among my friends for years.

Of course, I have also bought entire journalistic archives (e.g., from Horst Hamann in Bavaria) and society archives. Or, a few months ago, an airmail/aerophilately archive of Kuno Sollers.

Nevertheless, much would not have been possible without the close cooperation, the exchange of ideas and material with other experts and renowned philatelists. Besides Escalada, I would like to mention Tomas Bjäringer, Jonas Hällström, Chris King, Chris Harman, Leonard Hartmann, Vincent Schouberechts, Brian Birch, Jan Vellekoop, and, and, and . . . now I have certainly forgotten 20 or more! There are also some new names in Germany who have already made their mark on philatelic history through their contributions. I would like to mention Hans-Peter Garcarek and Thomas Schiller as examples.

Which of your books gave you the most satisfaction in terms of researching and writing?

If you had asked me this before 2016, I would probably have said the Moschkau book.14 Today I say the book about Philipp von Ferrary.15 It was the most difficult of all. Even in his lifetime, Ferrary knew how to lay a false trail, to collaborate in false legends himself. 90% of what has ever been written about Ferrary is, in my opinion, inaccurate, false, or contains at best only partial truths. Finding this out was made possible for me by an archive stock of a Belgian collector. For 40 years, Karel Langenaken had collected everything he could find about Ferrary in primary and secondary sources, in the state archives of various countries as well as in specialist journals, etc. I was able to acquire this truly extensive archive. Then I went on research trips to Austria, Italy, France, England, etc. My holdings had already been quite extensive before, but now they became downright lavish!

I have rarely invested as much in a book as I did in this one. All these journeys, some of them lasting weeks, cost money. So did the translations from French or transcriptions of 19th century manuscripts. But it was worth it. And when I told Vincent Schouberechts about the idea of having a special exhibition in Monaco on Philipp von Ferrary, and that I would be willing to write a book about it, he and especially Patrick Maselis were thrilled. That was exactly what Monte-Carlo liked to do. And so, a book worth reading was born. It is available in German but also in English/French in a somewhat shorter version. It is and will remain my favorite book. I hope to be able to publish a small supplement in a few years' time.

Most of your books are in German. This means that a big part of the philatelic world, people who do not know the language, are not able to read your books. Given that it has been quite inexpensive to translate German into English using online tools, are you thinking of bringing out English language editions of your earlier works?

It is true. The vast majority of my books have only been published in German. Only in recent years have some works also been published in English, and, if published by the Club in Monaco, also in French. Unfortunately, I have no linguistic talent. I speak a little English myself, but I am not a “native speaker.” This means that when I write in English (and of course I use the support of reasonably good translation programs to save time), I need an editor. In Philip Robinson FRPSL, I have found a friend who does the laborious work of proofreading works that seem suitable for translation and putting them into the right form.

For other works, I enlist the help of Rainer von Scharpen. Sometimes my sister-in-law Andrea Trost, who speaks French and Italian well, helps. In my opinion, however, it makes little sense to translate every one of my works into English. I will illustrate this with a few examples. At the moment I have finished a book manuscript on the “Spiro Bros. and their so-called facsimiles,” at least the first volume. The subject is a topic of interest to the worldwide philatelic community and I have worked on it with Chris Harman,16 Leonard Hartmann,17 and countless other philatelists. This book manuscript is therefore now also available in English and will probably be published in two-language versions in six months.

I have completed a book manuscript on “Wilhelm Sellschopp and his descendants” for typesetting and later layout. This is a family and company biography of one of the oldest stamp companies yet existing in Germany. German collectors are likely to be interested in it. Is an English edition worthwhile? I think not. In addition, we do not have sufficient sales platforms for English books.18

The same applies to an anniversary book of around 800 pages, which will be presented in Bonn on November 7, 2021. It is dedicated to the history of “75 years of the Bund Deutscher Philatelisten,” upon which I have worked on for the last 25 years. Very different, very extensive. Who abroad is interested in it? I think hardly anyone. That is why there will be no English translation of it.

Unfortunately, digital translation programs are not yet so perfect that translations can be reproduced without any editing. I would also like to see more and better software but not every dream comes true quickly!

You used to run a philatelic press service. Could you tell us more about it?

Since the 1990s, Claudia and I, later joined by our son Michael, have been working professionally for magazines and publishers. In 1995, we bought from a journalist colleague his weekly information service called Die Briefmarkenecke (The Stamp Corner), which he published for subscribed daily newspapers. Well-known and large newspapers were included such as the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, the Süddeutsche, the Münchener Merkur, etc. At that time, these newspapers received duplicated texts and photos as inserts about news, topics of the week, and so on.

But the wind was changing. Daily newspapers became less and less interested in philately; they no longer maintained “stamp corners” in their Saturday editions. PCs, computers and modern electronics of all kinds now took precedence and displaced philately. So in about 1997, when the Internet offered ever better possibilities, we switched to a digital press service, which still exists today under the name of Phil*Creativ Pressedienst (pcp). A small number of other journals, societies, and institutions are interested in this and can use these materials for their readers and Internet users. I think we will phase this out in a few years at the latest.

You have been working in German organized philately for a long time. Tell us how you got into it and some of your most memorable experiences?

It all began in 1974 with my membership in the Dülken, Viersen district stamp collectors' society. I was soon its chairman. Two years later I became head of the public relations department of the North Rhine-Westphalian Philatelic Society, and two years later again was deputy head of the public relations department of BDPh. I enjoyed working for the society, developing new ideas and more, simply being creative. Together with my friend Reiner Wyszomirski, who was appointed head of the Federation office with me in Frankfurt in 1978, we created an endless number of new products, designed effective promotional presentations for the Federation and so much more. It was still the time when money was plentiful.

In 1993 this became so extensive (at that time we managed the magazine philatelie with 10 annual issues, increasing a few years later to 12 issues) that Claudia (she was a secondary school teacher until then) left her first job and I virtually halved my position at the school. We had founded Phil*Creativ as a company in 1990 and it was not only a publishing house but an advertising/editorial agency. Since we were both still civil servants when we took over philatelie, it had been necessary to distinguish cleanly between profession and “hobby” at first. The “hobby” then became more and more of a profession, especially for Claudia.

As an agency, we took care of the entire philatelic PR and press area of the IBRA 99 international exhibition in Nuremberg, but also the NAPOSTA 2001 national exhibition and others later. For BDPh, we produced all the necessary small or larger advertising brochures, all the advertisements, all the flyers, etc. We were also in charge of all the press activities. At times we alone had five or more people working full time in this area. Strictly speaking, Phil*Creativ was founded because of and for the society.

To be sure, your wife, Claudia (Figure 6), is not just your life but also your work partner! How did she get involved in the business? What aspects of the business does she handle?

That came about rather by chance and became possible when our children grew up. She was a maths teacher, among other things, and from 1982 we experienced the exciting new PC era together. By 1983, I already had a large PC system with a printer (Commodore 9000 series). She was interested in programming. We had our first MS-DOS PC and we met Frank-Peter Lellek, a philatelist but also a programmer, in 1985. I developed concepts; Claudia and later Lellek implemented them in software programs. This is how the first stamp management programs, literature, club and society programs, even word processing and album design programs for collectors came into being. The philosophy was simple: every program had to be operated with only three key rules: idiot-proof, simple and fast. Later, programs for professionals followed, including an auction program that I helped develop but Lellek programmed alone.

Claudia worked her way into all areas of the company. She learned accounting (she still does our balance sheet accounting today), she became a media designer and IT specialist. She was so successful that the Chamber of Industry and Commerce appointed her as an examiner for media design trainees. Whenever there is a technical problem to be solved, she is there. She is as curious and inquisitive as a child and is constantly learning - even today. Without her, I would have been completely lost. I am just the hack; she is the universal genius!

You are considered to have one of the better philatelic libraries in Germany and perhaps in Europe. Which aspects of philatelic literature is your library strong in?

I do not want to overestimate my library. It is a working library and I am not a bibliophile literature collector, at least not today. For my editorial work since the 1980s, I needed standard works for my own reference. Journals were also indispensable for my philatelic history research, from the early 1860s up to today. There are no philatelic libraries near me, so I wanted to have all this myself. I think my library is still quite strong especially in German journals but also in English periodicals.

As far as the bibliophile things are concerned, I have begun to sell some items, precisely those that I no longer need for my current and future work.

While we are talking about your library, recently you started selling parts of your library on one of your websites – https://philshop.de. Why?

It has to do with my age. I am 72 years old and will not live forever. I do not want to leave my children the task of selling such a large library with many thousands of books, duplicates, auction catalogs, with countless archives, etc. Michael keeps everything he needs for his work in the future; I part with what I expect to no longer need. I have started with a small, manageable bibliophile section and with auction catalogs. At the moment, the first parts of the postal history section are also there, but that will take some time, because my constant book projects are more important. I am keeping the journals that are not digitally accessible for the time being.

My problem is that I often bought whole stocks at auctions, even when only I was only missing or really interested in some of the books. That's why I have thousands of books as so-called duplicates that simply didn't interest me and are just lying around in our house. So, the idea of offering them individually in an antiquarian bookshop was obvious, especially since the company can also make some sales that way.

When you were buying philatelic literature, you must have had many competitors (and maybe friends). Can you tell us about some of them? Can you recollect some interesting anecdote?

I have already mentioned some names before, names of literary experts who, like me, were or are on the lookout to land rare books for themselves. Of course, we sometimes got and still get in each other's way. I noticed this several times with Eduardo and Vincent. We got on each other's nerves - nolens volens - at Cavendish and Schwanke, and then only found out about it afterwards when we proudly told each other about the new acquisitions. Tomas Bjäringer from Stockholm may also have been indirectly in a bidding duel with me on many occasions. Now no more, or at least less, because apart from old albums from the 19th century, my “hunger” is quite satisfied.

Could you name some of your favorite philatelic works (not written by you) and the reason for choosing them?

I had already mentioned Dr. Manfred Amrhein's multi-volume work. In terms of the history of literature, this is still in the first rank for me. It is sad that the last intended fifth volume never appeared and nothing more was heard from Amrhein. What I could find out on the Internet sounded very disturbing. Carlrichard Brühl's History of Philately was and still is a monumental work for me. I also love Robson Lowe's Encyclopaedia, many good standard works on the Cape of Good Hope, British Guiana, and endless other areas that I still acquire. It is difficult for me to single out any one. Every book worth reading becomes my favorite until the next one comes along.

However, I would like to highlight one person’s life's work – that of Brian Birch (Figure 7). For me, he is the greatest philatelic bibliographer of all time. I have all his works, most of them digital. But that is enough. For me, they are an inexhaustible source of knowledge and valuable references.

You mentioned over our Skype call that you started your publishing business in 1986. Why did you get into publishing? Did you have a printing press also?

Yes, we had our own print shop from 1988 to 2008 and in 1986 I founded the forerunner of Phil*Creativ (called “WM-Verlag”). The background was that I had previously written several books with such great success that I thought we could do it ourselves. In the 1990s we bought a professional monochrome printing machine so that we could at least print in black and white by offset. For a while at the beginning of the new century, we also published and printed a two-color local magazine for Schwalmtal. But the digital change required investments that exceeded our possibilities. So, in 2008 we handed over the print shop to our younger successor, a master media designer trained by Claudia. But by then, we had produced countless small and larger writings by other authors.

Your company also sells albums and album pages. Given that there are so many philatelic accessory companies, especially in Germany, such as Lighthouse and Lindner, why did you start doing this?

This has something to do with the collector in me. For my archival materials, I have always been concerned about finding the best possible and most affordable storage options. When the debate about the harmfulness of PVC films started 20 years ago, we intensified our productive efforts, which were primarily geared towards exhibits. In the meantime, we have had only polyester and polypropylene covers in our range for years, and the cardboard produced by large well-known paper manufacturers also meets conservation standards. We have the albums, including our A4-Plus albums, produced by Leuchtturm (Lighthouse) and we are very satisfied with them. Our customers are too, especially as we offer them at a very reasonable price. For us, however, this is more of a mini-business.

You once told me that while your interest lay in philatelic history, while your son, Michael's, interest lay in postal history. Apart from that Michael is involved in running the family business as well. Tell us more about both these aspects.

After his A-levels, Michael did not know what to do at first, but finally decided on German and English studies. He studied, successfully completed his M.A. degree and then faced the same question again. I advised him to do a traineeship at our publishing house instead of sitting around at home, and so he joined us in 2008, but he had already worked for us on the side years before. He did not collect stamps; he never had. I think I was a cautionary example and not a good father (although we always got along very well). But I was always on the road and as a professional education scientist I did not want to treat my children as “guinea pigs.” Claudia brought them up, we shared the other work. We also had English au pairs when the children were small.

Michael is very clever; he's probably more like Claudia. Unlike me, he never worked on Saturdays, so I handled the mail on Saturdays. About ten years ago, I accidentally opened a letter addressed to him from abroad. Astonished, I saw the contents: some postal stationery. This happened again and so I asked him if he was suddenly collecting. He nodded and I learned that his interest in philately had been awakened. At that time, he was already designing philatelie and editing my and other authors' texts. From year to year, he worked himself deeper into the subject, acquired small and larger stocks of postal stationery and covers, and became quite a connoisseur because he absorbed knowledge like a sponge.

Two years ago, we gave him the job of managing director of our company. After we lost the contract for the production of the magazine philatelie at the end of 2016, we downsized our publishing house so that the company now consists of only three people, with the two of us (Claudia and me) being discontinued models! He and his wife Sarah have three children who are still very young at the moment. As soon as the youngest son starts kindergarten, his wife Sarah will rejoin the team. I find it very gratifying when you can work together so harmoniously as a two-generation team.

Over the years you have been the editor of numerous German stamp magazines and journals. Tell us about your time editing those magazines?

From January 1989 to January 2017, we took care of the magazine philatelie completely with all the tasks that came up. It changed our lives; as a family, we had to follow deadlines for issues and other necessary work. Time management became important. Even on holidays there was no break. The computers always went with us. Today, thanks to the Internet, many things are easier that were still a problem in the 1990s; for example, data and communication traffic.

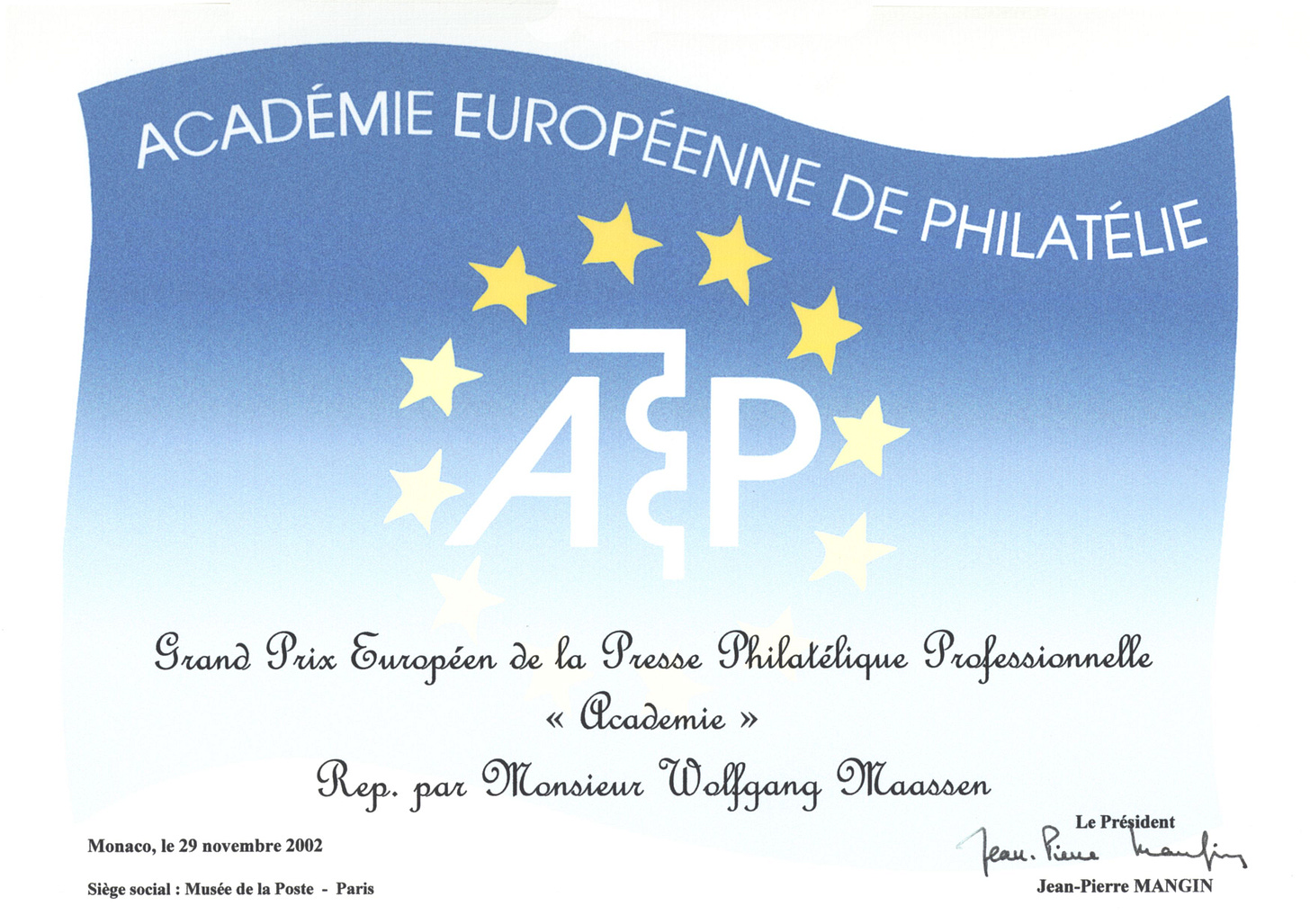

philatelie was and remained an affair of my heart. In the best of times, it had over 80,000 subscribers and readers every month. In 2003 it was voted the best philatelic journal in Europe by the European Academy of Philately, which we were understandably delighted about (Figure 9). What fascinated me so much was the range of topics. For many years I had an editorial assistant (Beatrix Vieth, later Stephanie Hackel and others), because the workload could not be managed alone. After all, I still had a “half” teaching position at the college until 2011.

philatelie has often kept us on our toes. For example, when ad copies arrived only at the very last second, we had to send the necessary artwork/files to the printers by car or courier. Or when our computers suddenly crashed and Claudia had to work all night to get everything up and running again. But one forgets the problems and retains the pleasing fact that in almost 28 years we have always managed to bring them out on the exact day.

In 2005, I became President of Association Internationale des Journalistes Philatéliques (AIJP), the International Association of Philatelic Authors and Journalists.19 This association was coming to an end at that time. With a few loyal helpers, we rebuilt it, published a sensible journal, which I have been in charge of – except for two years – up to today. The Philatelic Journalist is a bilingual magazine for which I write many articles.

In 2010, the then-monthly magazine APHV-Magazin was added. APHV is the abbreviation for the Bundesverband des Deutschen Briefmarkenhandels or the Professional Association of the German Stamp Trade.20 The president at the time, Arnim Hölzer, asked me if I or we could also take care of this magazine. It was 40 pages per month, which had to be filled editorially, designed and then produced, including mailing to the 400-500 members of the association. We have been doing this ever since, even though the magazine has only been published bimonthly for a few years now.

In 2013, you started the online quarterly magazine for philatelic history and literature enthusiasts called Phila Historica (limited copies are also printed every year). How did you come to this? And where do you manage to get the motivation to edit and significantly contribute to almost 1,000 pages of this magazine per year?

Phila Historica is a very specialized journal for friends of philately and literary history. This journal also has a predecessor history that is connected with philatelie. My interest in writing about special topics in philatelic history had grown over the years. I was able to place some things in philatelie, some in APHV-Magazin, but only fractions. Even this proportion was too much for some people on the associations’ board. I felt that I had to change something. So, I came up with the idea of a free digital magazine in which everyone, including me of course, was no longer bound by size limits. It is free also because I did not want to found a society with all the regulations as in a publisher's association. I also did not want to start a subscription magazine, whether it be digital or print, because that would have entailed the time-consuming collection of subscriptions and much more. Here I could let off steam in the truest sense of the word, writing articles of 30 or 50 pages or more, and devoting myself to any topic that seemed interesting and worth preserving.

Michael designs the magazine and I look after it editorially and as an author. For some friends and interested people, there is the annual anthology of four issues each with up to 1,000 pages, but printed in black and white. Otherwise, this would not be affordable, but digital printing makes many things possible.

And if it somehow works and my health allows it, I would like to keep this up for a while. How long? That remains to be seen.

In the latest July 2021 issue of The Philatelic Journalist, I see that you have not only written the editorial but that each and every piece has been contributed by you! Furthermore, you also manage the AIJP website. Do you find it is disturbing and sad that you do not get much support?

I do not manage the AIJP website. The work of posting current news has been with Vincent Schouberechts and Dr. Mark Bottu for some time. But they receive our “pcp news” and can then choose what they think is interesting for the AIJP site. They may also translate the German texts. Unfortunately, there have been problems for some time, allegedly due to technical difficulties.

I take care of the Philatelic Journalist myself, write many articles and have them translated (mostly by Rainer von Scharpen) so that they appear bilingually. The fact that one issue is filled almost exclusively by my contributions (interviews with well-known professional philatelists) is a coincidence. It is due to the Covid pandemic, because hardly any events take place anymore, so that special pre- and post-reports are omitted.

Of course, I would be very happy to receive contributions from other members. But they have to fit the profile, i.e., they have to bring a journalist something of added value for himself and his work. It is not so easy to bring something new to the table. I have tried to do this for years with my guides for authors, literature collectors and for journalists, i.e., with topics on copyright and/or image rights, etc. I only hope that times will soon change again and become more normal. Then the range of topics will also become broader and maybe one or two people will reactivate and join in.

Earlier this century, you published Chronik der deutschen Philatelie [Chronicle of German Philately] for the years 2002, 2003, and 2004. This work chronicles German philatelic events and personalities in a particular year. Earlier this year, you came out with a digital edition for the year 2020. Why did you not publish it for 15 years? Was it due to work-related pressures?

There were special reasons why I stopped in 2005. My original plan was to present a so-called “reader” for each year from 1860 to the present. In other words, purely textual volumes in which what was worth preserving was printed with references to sources. I had already finished the annual volumes 1933-1937 and wanted to continue with them. Then another author, whom I knew well and appreciated, complained to a third party that I was taking the butter off his bread, because he wanted to write about the unfortunate period of National Socialism and the involvement of philately in the Nazi state. He saw me as a competitor, which I was not, but he felt that way. Hence, I backed off. Finally, I saw that the 2002-2004 annual volumes hardly sold more than 30 copies. No one seemed interested in receiving such research material. I found it valuable because who could access the sources I had? Who bothered to do so? I gave up the idea, even though I had already started with the early years of German philately at that time. Instead, I have since then only published the so-called “special volumes,” of which probably almost 20 will also have appeared by the end of the year.21

In the last two years I have compiled an annual volume for 2019 and 2020 consisting of the most important news from our press service and published it in Phila Historica. I will not have it printed, but at least the work will not be lost.

Most of your books are printed in limited edition of 100 copies. You produce your year books of Phila Historica in print runs of just 30-35. Further, recently you got the 2014 year book reprinted in a run of just eight copies! Printing houses do not accommodate requests for such small print runs and this results in excess copies of philatelic books being printed which remain unsold for decades. How do you manage to convince your printers?

In digital printing today, you can print single copies. This is expensive, of course, especially in color. But with 20 or 30 copies, you have a price that is feasible from a sales point of view, and you might still earn something from it. Compared to the past, this is always better than having 300 or more copies printed by offset (below that is not profitable) and then 200 or more copies lie in stock. They only cost expensive storage space, so in the end you can only give them away or dispose of them after many years.

For us, digital printing has been a blessing. Of course, you cannot make money in a professional sense with short runs of up to 100 copies. The author's work, including mine, was and is never paid. That is my hobby. I just always make sure that the cost of the typesetting, design work, and printing is recouped. Then I am satisfied. For the majority of the books, it works. We subsidize the rest through donations and through the books of our publishing house, which sell much better: the guide books and the encyclopedias of philately and cartophily, for example.

For Stockhomia 2019, one of the best stamp exhibitions, you wrote the superb Library Catalogue22 and were also involved in the day-long philatelic literature sessions that took place on all the days (perhaps never done before?) How did you get involved in this exhibition? What are your memories about organizing all those sessions where people from around the world (including me!) spoke about philatelic literature?

For Jonas Hällström, the spiritus rector of this unique exhibition, it was clear from the beginning that this major event dedicated to the 150th anniversary of the Royal Philatelic Society London (RPSL) was primarily aimed at philatelists from all over the world. Jonas is a bibliophile himself. He is a good friend of Tomas Bjäringer. Both live in Stockholm and work closely together. The idea of a special literature show was obvious to Jonas, originally envisaged as a show by the RPSL. In 2016 or 2017, he approached me to see if I could imagine working for STOCKHOLMIA, as an author, a member of the team, as President of the AIJP, and be responsible for a special and extensive literature section.

He asked me for a concept of ideas in which I was allowed to write down everything that seemed to make sense to me. Of course, Jonas knew that I had organized and conceived the IPHLA international literature exhibition in Mainz in 2012 and that I was also actively involved in a similar way with the MonacoPhil in Monaco in 2013; he was hoping for something similar for Stockholm. He received a multi-page concept with lots of ideas and he liked it. He invited me to Stockholm in 2017 where we discussed everything. I was very pleased that the other team members were also very enthusiastic.

Since the RPSL balked at stocking the envisaged literature area (in 20 showcases) for transport reasons (but later did a fantastic show of exhibits from the RPSL's museum holdings), we came up with the idea of asking Tomas. This was the best idea ever, because Tomas' library is, to me, one of the best there is in the world. He went to incredible lengths to stock the showcase literature display with the rarest works from the RPSL. He also helped me with the Library Catalogue like no other. I am indebted to him to this day. Mutual visits intensified our excellent cooperation.

Similar to the “Academy for Collectors” that I first tried out in Mainz in 2012, we planned an even more extensive seminar program for STOCKHOLMIA, limiting myself to the events in the literature section. The international participation was enormous, not only that of the authors and speakers, but also that of the audience and guests. For me, it was one of the great moments, a milestone, that will perhaps never be surpassed. I met so many new and previously unknown friends of literature, including you. It was simply unique.

For Tomas' museum literature show, I drafted the texts, which he then refined and which we then finally designed. It was such a uniquely good collaboration between all of us. I still dream of this today.

In 2014, you were invited to sign the Roll of Distinguished Philatelists. The Board of Election mentioned that “...some of his greatest contributions are productions on the history of philately itself.” What was your reaction to your election?

I was completely surprised. I would never have expected this in my life. Let's face it: if we look at the list of RDP signatories they have been great and important researchers, usually also highly awarded exhibitors, but mostly postal historians, traditional philatelists, perhaps aerophilatelists or thematic collectors (the latter only in smaller numbers). But authors, writers? All of the aforementioned have usually also published, perhaps one or more works that became standard works, but a philatelic journalist, a professional author, was hardly ever among them. Let us exclude Fredrick John Melville, who has always been a great role model for me.

With this decision, not only the person, but also the field of philatelic history was honored. This seemed even more incredible to me. For the first time I experienced recognition for a subject and topic to which the vast majority of all collectors hardly ever paid attention. I could hardly believe it, nor did I want to. And when I stand next to renowned researchers and philatelists today, I sometimes ask myself: “Wolfgang, what are you doing here anyway?” Then I take it upon myself to prove myself even more worthy of this place in the future by realizing what is possible with my modest powers. It still spurs me on today; it gives me motivation, drive.

In March 2021, the Board of Election of the Roll of Distinguished Philatelists added the names of the German Alfred Moschkau (1848-1912) and the Austrian Victor Suppantschitsch (1838-1919) to the Roll as “Fathers of Philately.” The Board had access to your guidance in selecting them, thus reversing a historical injustice. How did this come about and why did you suggest these two gentlemen? Were there others you considered?

It was Chris King who had this idea. Chris is someone who thinks, acts, and lives internationally. He and his amiable wife Birthe have always been aware that it is impossible to make up for the past injustices that people have brought upon people – that one should not forget but preserve, but also that one can reunite and start anew. Chris himself was Keeper of the Roll for a while and he knew that there were two vacancies there with the so-called “Fathers of Philately.” Originally there were four, but two more had already been filled. Chris also knew the reasons why this was so.

In 2011, on the occasion of a bilateral exhibition in Hanover, I explained in more detail about the enmity between the German and English people, who were originally so close to each other, which had arisen as a result of the unfortunate and terrible First World War. I spoke about the hostile feelings between the noble clubs of the time, for instance between the RPSL and the Berlin Philatelic Club and/or the Vindobona. Well-known German philatelists of the time, such as Carl Lindenberg and Dr. Franz Kalckhoff, returned medals awarded to them, as did Victor Suppantschitsch. On the English side, equally renowned philatelists followed this example.

We both knew why this was the case. Chris had the idea to change this for the 100th anniversary of the Roll. He asked me whom I could think of who would have been eligible for it before 1921 if everything had gone differently. I gave it some thought and suggested a number of names to him. Not only Alfred Moschkau and Victor Suppantschitsch, but also Theodor Haas, Dr. Kloss, or Heinrich Fraenkel who all had a stature that seemed to me worthy of consideration. There were more, also on the Austrian side. But only philatelists who had already died in 1921 were considered. Carl Lindenberg, for example, was excluded.

In any case, I am pleased that Chris King was able to make his idea palatable to those in charge and that Moschkau and Suppantschitsch were approved. Both deserved it in their own way and I believe that this makes up for a small chapter of historical injustice in which we Germans played a considerable part.

I still have some hope that we will be able to travel in person to this year's British Congress and attend the upcoming RDP ceremony where these two names will also be added. Let’s hope that a trip to Harrogate on September 24, 2021, will be possible.

In your own biography published in volume 4 of “Who is Who...?”, you mention your residence as not only Schwalmtal in Germany but also Denia in Spain. Do you go to Spain in the winter? Do you do any philately when you are there?

There are two countries that are particularly close to me and my family. That is England, which Claudia and I discovered for ourselves as young students in the early 1970s with an English host family. The first stay was followed by a close friendship with this Cronin family, which took us to Brighton/Hove and London five or six times in some years. One of the daughters of this Cronin family, Samantha, was an au pair with our son Michael for a year. The contacts still exist today.

We increasingly discovered Spain for ourselves in the 1980s. We usually spent three weeks there in spring and six weeks in summer, sometimes two weeks in autumn. We bought a large caravan and moved with bag and baggage (including the PC, of course) to large campsites where we could set up and work luxuriously in the awning with our PC equipment, with which we produced philatelie. The neighbors were always amazed when I worked at the PC all day! For the children, this was the best and freest kind of holiday they enjoyed. And we enjoyed the peace and quiet, because they were always out with friends and other children.

Over the years, we noticed that we increasingly visited the same places in northern Spain. At the turn of the millennium, we had a very unpleasant 14-day stay in Miami, Florida, because our children had wanted something “special.” We booked at a high price via the Internet and were tricked, ripped off, gutted like a goose. That was enough for us and we decided to settle in Spain for the future. We came up with the idea of buying a house on the Costa Blanca in Denia. We have been staying there for 20 years every year for a few months, not only in winter but also in spring or autumn. We only skip the hot summer months.

Because of Covid, it is now a year since we last saw Denia. But our children, who now have small children of their own, have discovered it for themselves and their families. So, it is a perfect fit and we are happy that the house is being used more again.

And as for work: I said I am a workaholic. Of course, we have our workrooms and our PCs there too. We just change jobs, but enjoy the Spanish mentality, the far nicer warmer weather, the good varied restaurants, the wine, air, and love. Including a 13-km long, mostly lonely, empty sandy beach. Many philatelists have already discovered this little paradise, which fortunately is not yet so overrun by tourists. For me, Denia is a balm for the soul.

Acknowledgments: I am thankful to Wolfgang for his detailed answers to my questions. That he is a workaholic is apparent since he responded to my long list of questions within 10 days of receiving it. Thanks are due to Philip Robinson for checking the translation of the answers. Feedback and comments can be sent to my email id: abbh@hotmail.com.

Phil*Creativ is a combination of two words: Philately and Creative. The star is a symbolic symbol for ad astra (a Latin term meaning “to the stars”). In Germany, special characters are allowed in a company’s name.

That is, the first state examination, the conclusion of a full university course of study, quasi corresponding to the M.A. (Master of Arts or Magister Artium).

Bonn was then the capital of the Federal Republic of Germany or West Germany.

Automatic stamps are produced individually by a machine on demand in a denomination selected by the customer. There normally is no date on the stamp, as there is on a meter stamp. They are also called ATM, from the German word ‘Automatenmarken’. See https://www.linns.com/news/postal-updates-page/glossary-terms-disabled.html

Sammlerdienst came out from 1949-1991. Thereafter it is published under a new title, Deutsche Briefmarken-Revue, until today.

DBZ with its predecessor Frankfurter Briefmarken-Zeitung has existed from 1924 to present.

A bibliography of Maassen’s long works (not including articles) can be found in Issues Nos. 3 and 4 (September 2017 and December 2017) of Phila Historica.

Brühl, Carlrichard. Geschichte Der Philatelie. 2 vols. (Hildesheim, Germany: Georg Olms Verlag, 1985-86).

Birch, Brian J. The Fathers of Philately Inscribed on the Roll of Distinguished Philatelists. (London: The Royal Philatelic Society London on behalf of the Roll of Distinguished Philatelists Trust, 2019).

Maassen, Wolfgang, and Vincent Schouberechts. Milestones of the Philatelic Literature of the 19th Century / Les Jalons De La Littérature Philatélique Au XIXe Siécle. (Monaco: le Musée des Timbres et des Monnaies de Monaco [Club de Monte-Carlo], 2013).

Amrhein, Manfred. Philatelic Literature: A History and a Select Bibliography from 1861 to 1991. 4 vols. (San Jose, Costa Rica: The Author, 1992-2006).

Maassen, Wolfgang. Dr. Paul Singer & the History of Shanahan Auctions: Five Years to the Top of the World and a Deep Fall. (Schwalmtal: Phil*Creativ GmbH, 2019). Also published in German.

Maassen, Wolfgang. Alfred Moschkau. Philatelist, Heimatkundler und Museumsgründer [Alfred Moschkau: Philatelist, Local Historian and Museum Founder). From Chronik der Deutschen Philatelie [Chronicle of German Philately], Volume 5. (Schwalmtal: Phil*Creativ GmBH, 2012).

Maassen, Wolfgang. The Mysterious Philippe De Ferrari: Collector, Philatelist and Philanthropist / Philippe De Ferrari, Cet Inconnu: Collectionneur, Philatéliste et Philanthrope. (le Musée des Timbres et des Monnaies de Monaco [Club de Monte-Carlo], 2017). Note that this is the English/French version and the book was also published in German.

Christopher G. Harman is the past President of the Royal Philatelic Society London and the current Chairman of the Society’s Expert Committee.

Leonard H. Hartmann is best known as a philatelic literature dealer but he has a keen interest in forgeries. He was interviewed by me in the Fourth Quarter 2020 issue of the Philatelic Literature Review.

The family’s firm, Phil*Creativ GmbH runs two websites: https://philshop.de for antiquarian books and https://phil-shop.de for their own publications, philatelic supplies, and for hosting the journal Phila Historica.

The first of these “special volumes” came out in 2006 and was titled Ludwig Hesshaimer: Licht und Schatten – Liebe und Leidenschaft – für Kunst und Philatelie [Ludwig Hesshaimer: Light and shadow - love and passion - for art and philately].

Maassen, Wolfgang, ed. Stockholmia 2019. Library Catalogue. (Schwalmtal: Phil*Creativ GmbH, 2019).