This article was first published as “The 'Enkakushi' of Japan an its Imitations” Philatelic Literature Review 73 no. 3 whole no. 283 (Third Quarter 2024) and with the same title in Japanese Philately 79 no. 4 whole no. 455 (Fourth Quarter 2024). It is a co-publication of American Philatelic Research Library’s journal The Philatelic Literature Review and the The International Society for Japanese Philately’s Japanese Philately.

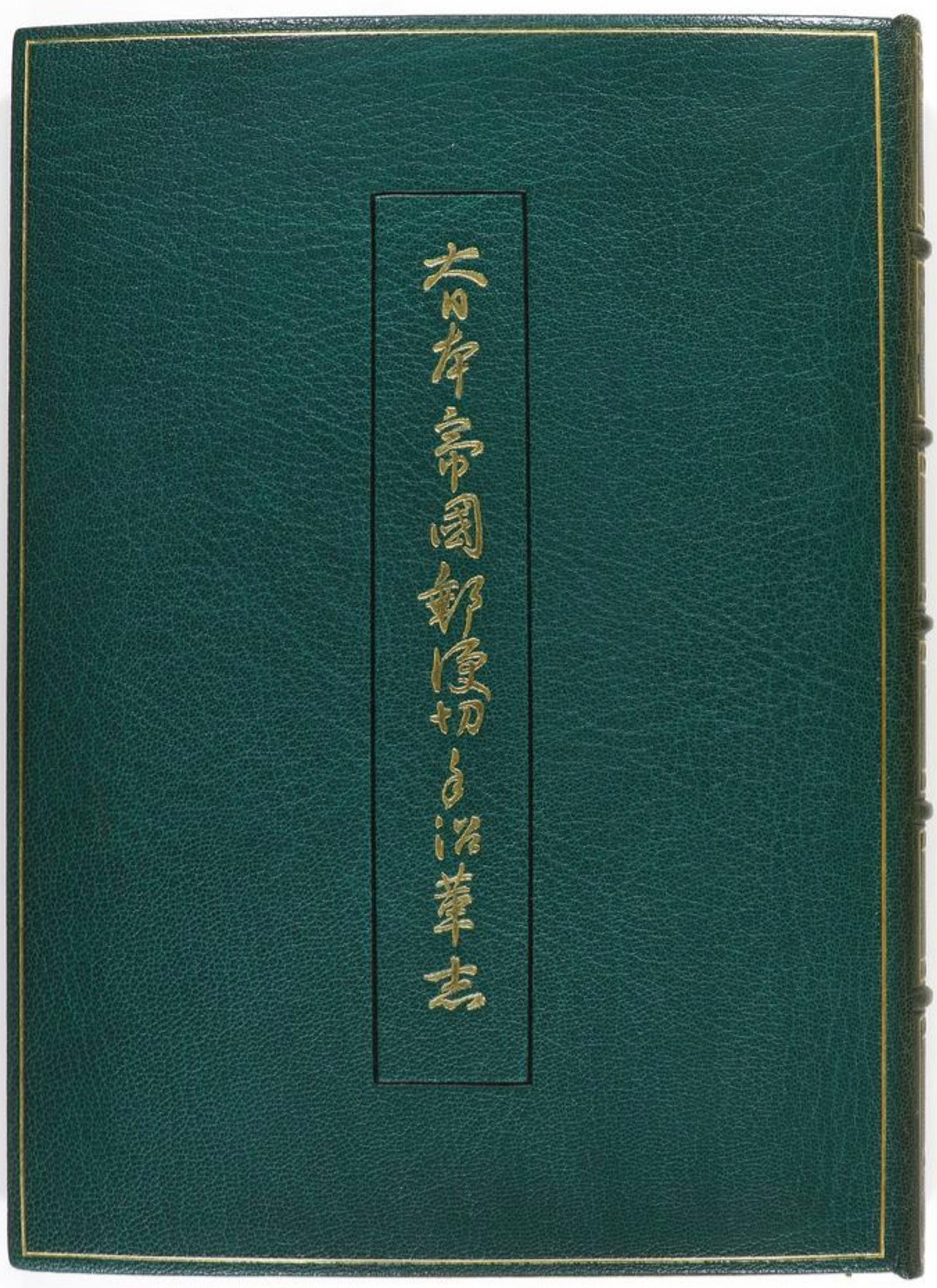

Few works straddle the worlds of both philately and philatelic literature. One such which does, and does so splendidly, is Dai Nippon Teikoku Yūbin Kitte Enkakushi.1 Call it a catalogue or a presentation album or just a book, it is undoubtedly one of the most beautiful works of philatelic literature ever produced.

While a literal English translation of the Japanese title would be “A History of the Postage Stamps of the Great Japanese Empire”, the eleventh page of the text (numbered as “1”) gives an English title “A Short History of Japanese Postage Stamps” (Figure 4).

The Official Enkakushi

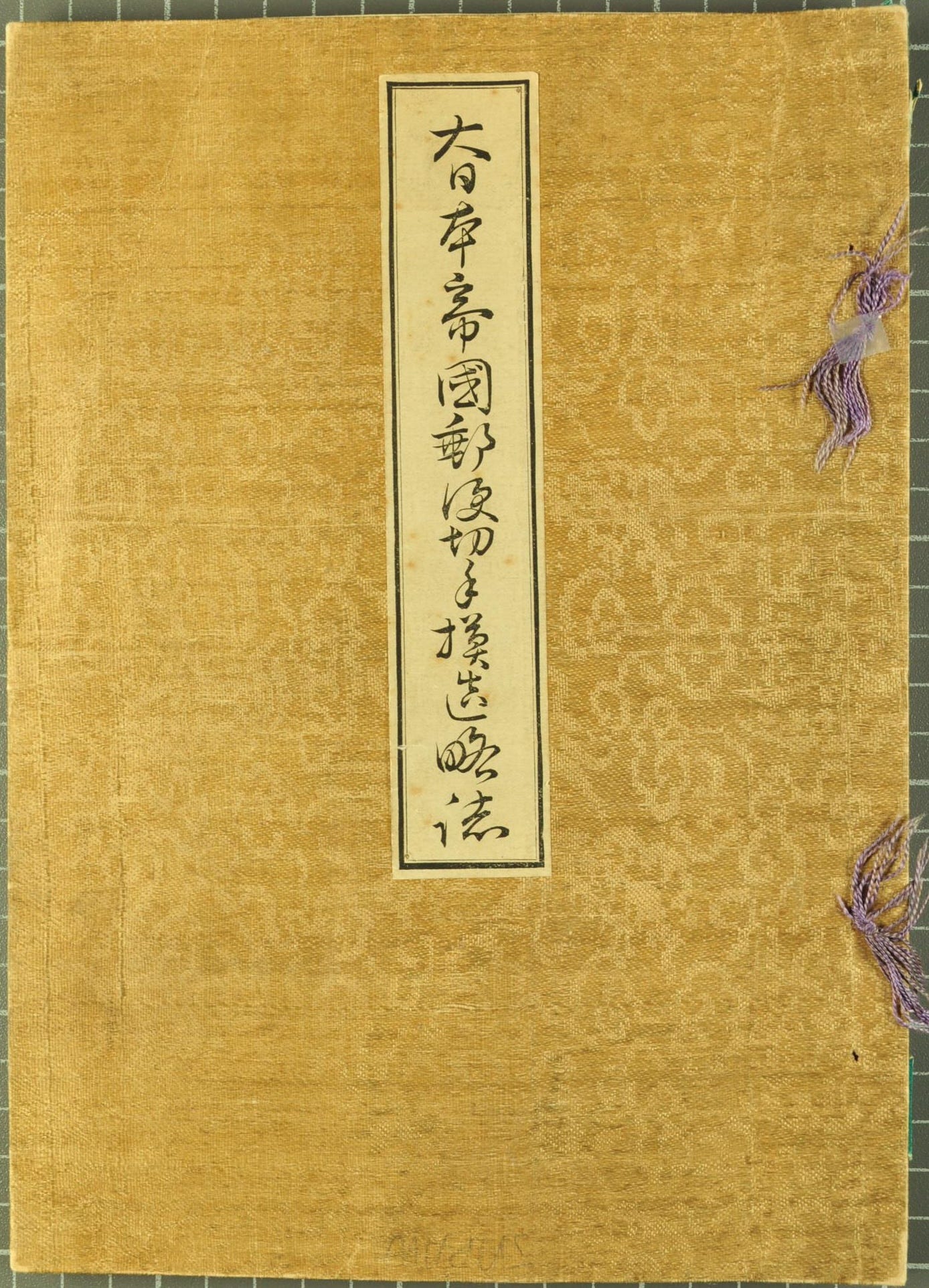

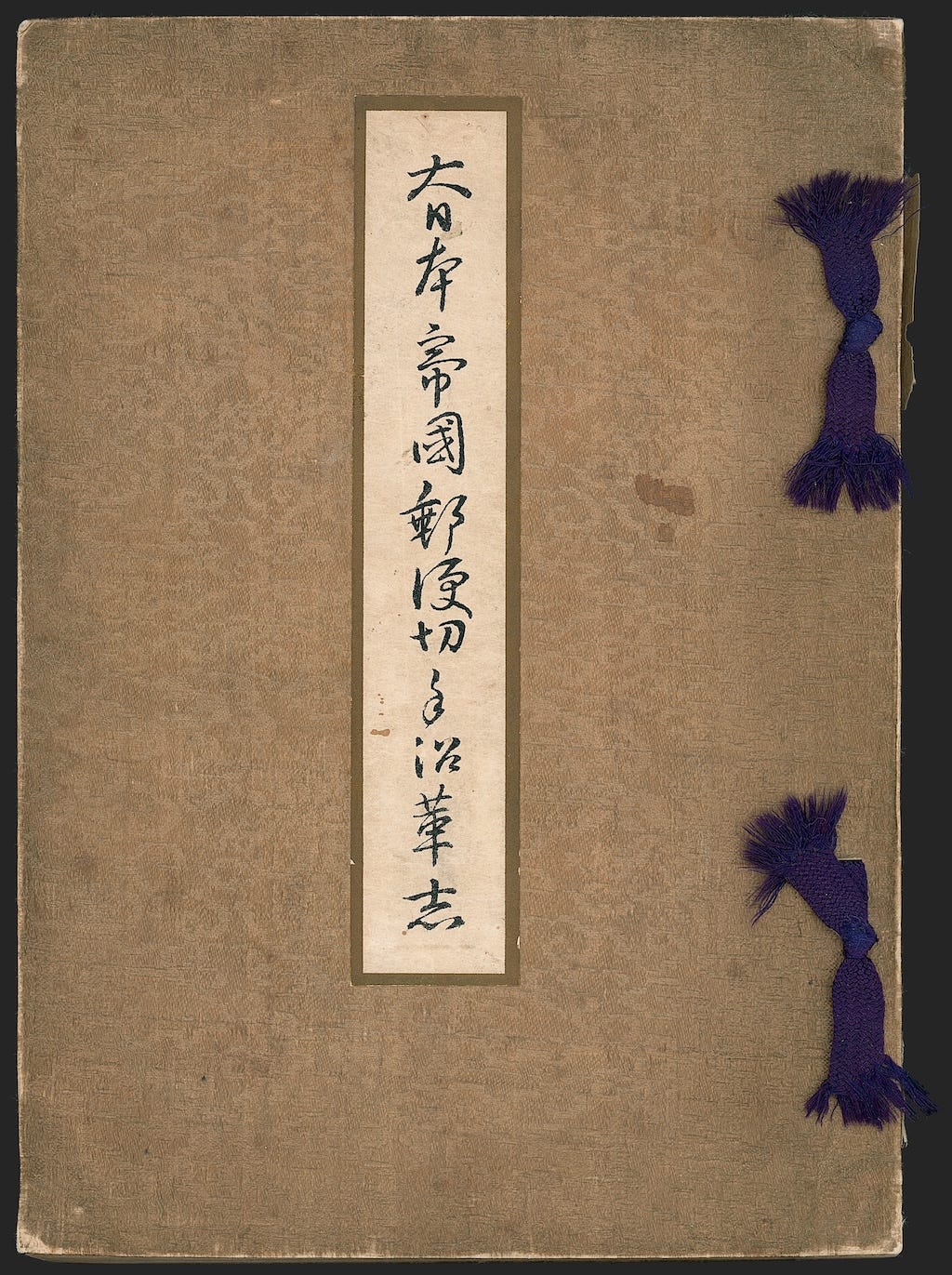

Dai Nippon Teikoku Yubin Kitte Enkakushi (Enkakushi or literally “History”) (Figure 1) was published by the Communications Ministry of the Japanese government in 1896.2 “Bound in the most bewitching golden silk brocade with purple bows” and “printed on the best of paper” (Japanese vellum), it is “fully illustrated by actual genuine specimens of each value, of each issue.”3

Genesis

The first stamps of Japan were issued on April 20, 1871,4 three years after the “Meiji Restoration”, which saw the transfer of political and military power from the shogun to the emperor and which, in turn, led to the industrialization, modernization, and westernization of Japan.

By 1892, the Japanese postal system was more than 20 years old. Few of its original personnel were around and its records were disorganized and incomplete. The Ministry of Communications (Tei Shin Shō), decided to compile a history of Japanese stamps from its records. Two junior officials from the ministry were chosen to do this: Hibata Shōtarō (Figure 2) and Ōkusa Tatsunari.5

After two years of research, Hibata and Ōkusa completed the manuscript in Japanese describing in chronological order all postage stamps, postal stationery, newspaper wrappers, telegraph stamps, and urgent message labels issued from 1871 to March 1894 (ending with the Meiji Silver Wedding commemoratives). If not for their efforts and despite the shortcomings of the work (often arising from inadequate or ambiguous records), knowledge of Japanese stamps would have been much less complete than it currently is.

The main text (excluding the statistical tables) was translated into English by an official of the International Mail Section, Kimura Ryōkichi, who was aided by a British advisor to the Foreign Affairs Ministry, William Henry Stone.

Publication Date

It is thought that the Printing Bureau completed the printing sometime in 1895. Then came the tedious task of affixing the specimens in each of the 300 (or 500; see later) copies of the book. This was likely done at the Communications Ministry and was completed by March 1896.

The colophon (inside cover, p.101) gives the date of (completion of) printing as March 4, 1896, and the date of issuance or publication as March 6, 1896 i.e. two days after the printing date.

Housing

The original housing is likely a sleeve made of stiff papers/carton. The front has the Japanese flag with the rays from the sun folded inside the sleeve. I base this on private communication with the noted bibliophile, Jan Vellekoop of Netherlands. He had examined the book, and what he considers to be its original protective housing, when it appeared in a Dutch auction in 2014.

Given how valuable the book is, copies with protective boxes made-to-order by later owners can be seen at auctions (see Figure 13).

Sale Price

The Enkakushi was never intended to be sold. Rather copies were gifted. In 1896, communications minister Shirane Sen’ichi gave one copy each to the emperor and empress, the 12 members of the cabinet, postal founder Maeshima Hisoka, the head of each postal administration in the Universal Postal Union (postmaster generals), other high officials and diplomats, and major libraries in Japan and abroad.

Contents

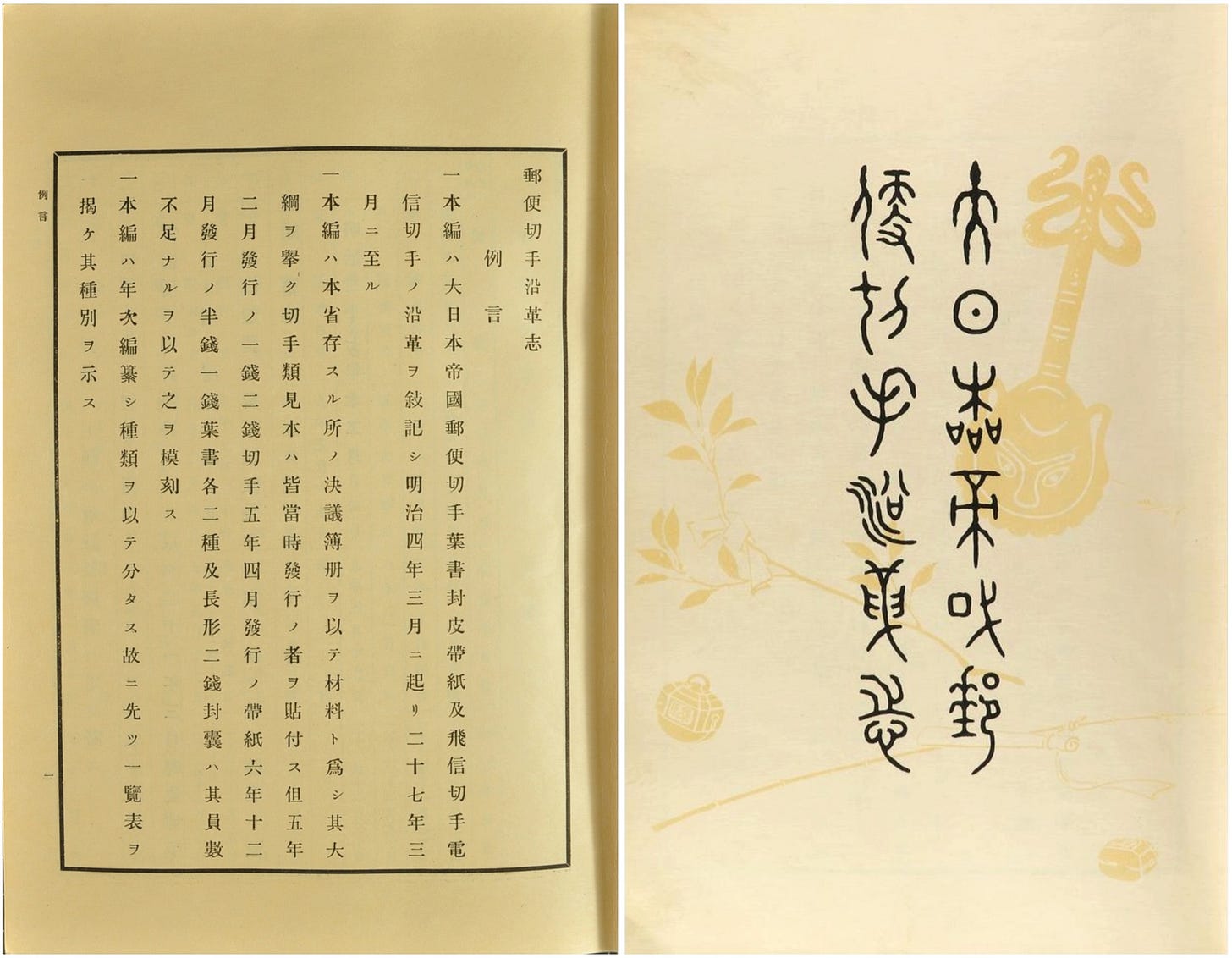

The title page (Figure 3) reads Dai Nippon Teikoku Yūbin Kitte Enkakushi. It is printed in archaic seal script (Tensho) and features background images of a bell with an ornate handle, which is seen on the 1-yen value of the Chrysanthemum (kiku) stamp series, and a small postal bell like those seen in the designs of the other stamps of that series.

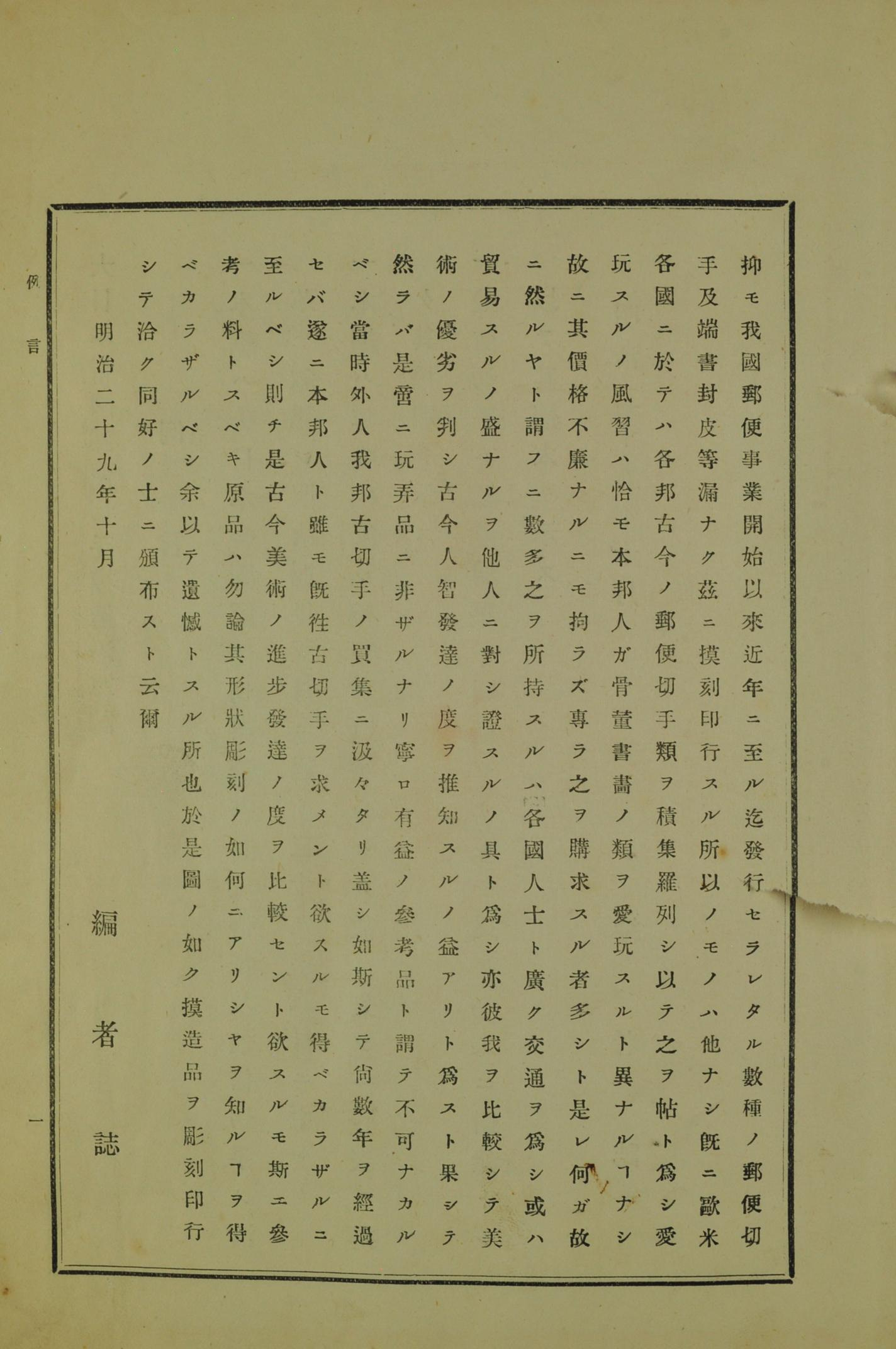

After the title page, on page no. 1, a foreword in Japanese follows (Figure 3; a complete translation is provided in Appendix 1).

The foreword states, among other things, that as the book compiles issues by date and classifies by type, a table is first presented to provide an overview of all categories.

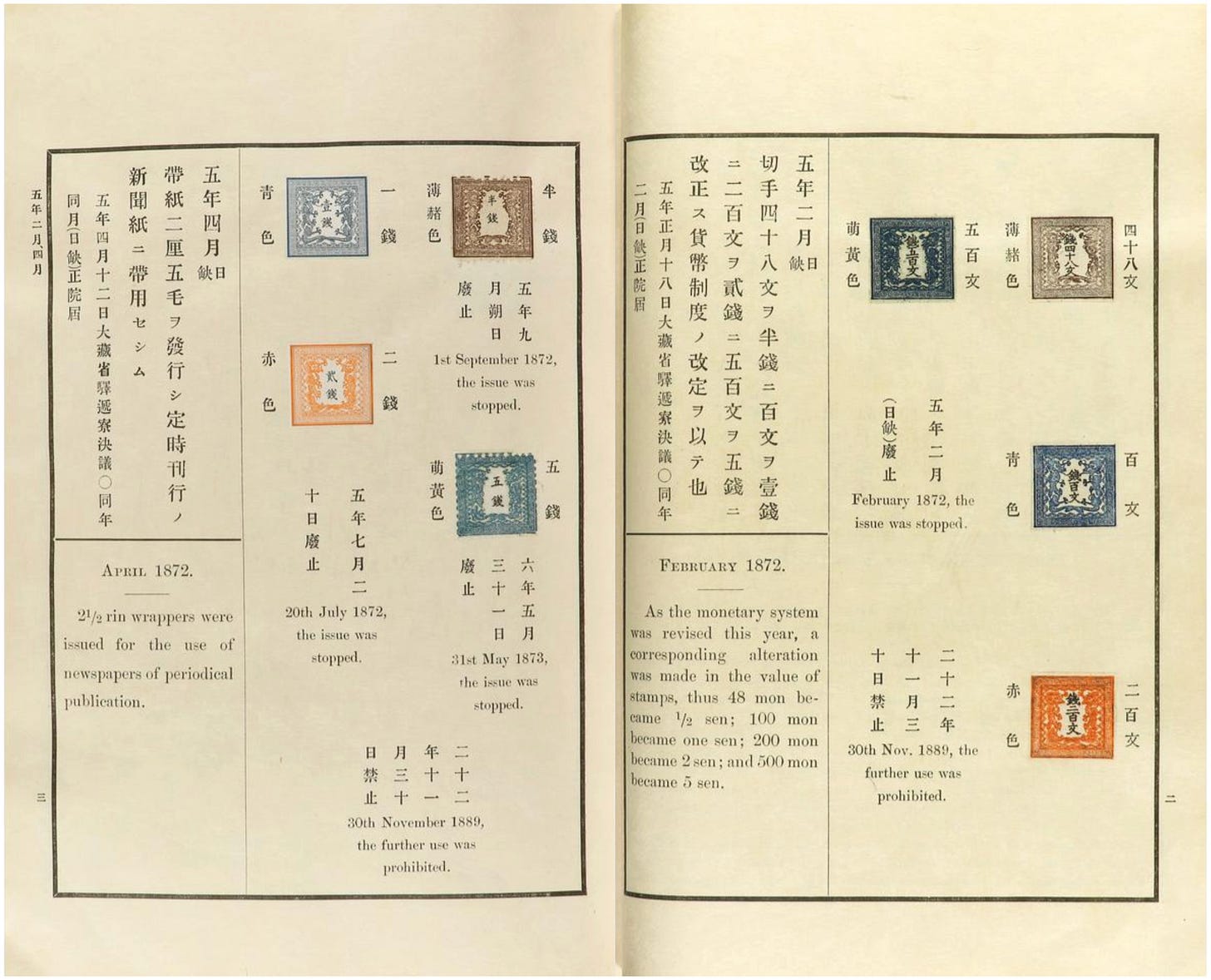

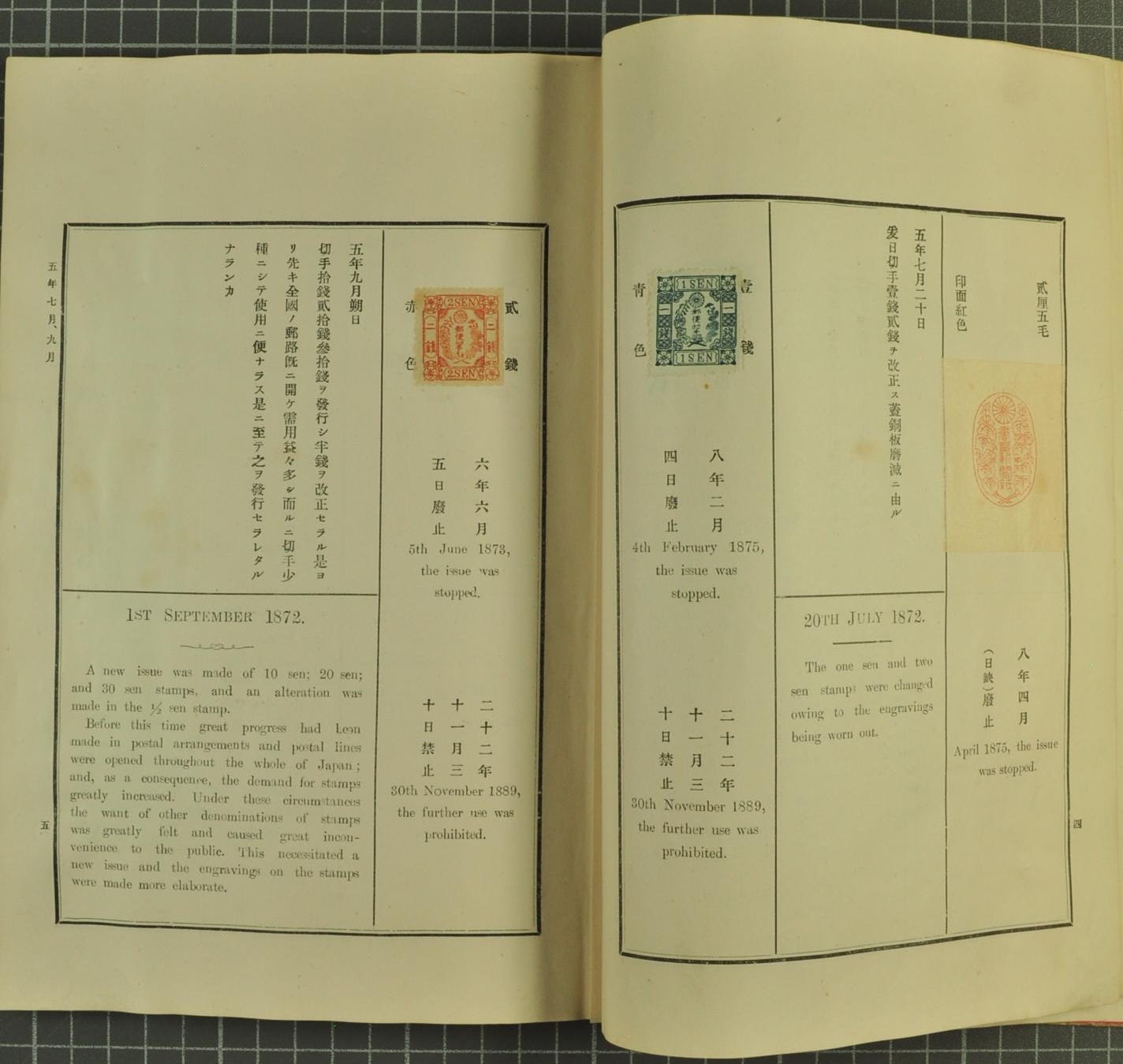

Then follow seven pages of tables which give an overview of the postage stamps, postal cards, envelopes, wrappers, and telegraph stamps. For instance, Figure 4 shows a table titled “Historical Table of Postal Cards”. It lists postal cards by face value, color, issue date, date discontinued, and date when use was prohibited, between 1871 and 1879.

On the 11th page by count, the page number is reset to 1. The top part introduces the work in Japanese and the bottom is written in English (Figure 4).

Thereafter, the text is bilingual, both in Japanese and English. However, the detailed description of stamps, etc. is in Japanese.6

Through genuine unused examples with a few exceptions, this book illustrates and describes the postage and telegraph stamps (Figure 5), postal stationery (envelopes, postcards, and newspaper wrappers) (Figure 6), and urgent-message labels which were issued by Japan between March 1871 and March 1894.

The book does not go into discussing minor varieties of stamps known to philatelists. For instance, while the Enkakushi recognizes 20 stamps in the 1872-76 Cherry Blossom series (Figure 7), stamp catalogues assign major numbers to about double that.7

However, it contains much new information, especially the reasons for new values and issues (Figure 8).

Statistical Tables

The book concludes “with an abundance of tables and schedules touching various branches of the post office department.” They contain information such as prices paid for manufacturing of the different stamps, numbers sold, and so on.

However, the tables suffer from many shortcomings. Even as early as the 1890s, many records had probably been lost and some records, which did exist, contained ambiguous or incomplete information.

Consider some glaring errors. For example, it shows the number of postcards sold to the end of June 1876 as 9,678,893 whereas it has numbers printed as 6,093,813; so 3,585,080 postcards that did not exist are said to have been sold! Another example: 12 stamped envelopes of 1873-74 were superseded on June 29, 1877 and invalidated for postal use on November 30, 1889; the tables show substantial quantities being sold post 1877 (possible but not probable in such size) and six sets being sold between April 1, 1890 and March 31, 1891 (curious as to how!)

Not a mistake but one example of what would be thought to be a deficiency by philatelists: it lists quantities sold by denomination; so, it makes no distinction between the 2 sen Cherry Blossom and the 2 sen Koban envelopes.

Summary of Pages

A summary of the contents of pages as recorded by Lieutenant Wilhelm Johann Paul Ohrt in his three-part 1897 article is given below:

Pages 1-70: Description of postage and telegraph stamps and postal stationery

Pages 71-76: Appendix describing official urgent service stamps

Pages 77-78: Quantity of printed postage stamps and their costs

Page 79: Manufacturing costs for 10,000 pieces

Page 81: Information on the quantity of postage stamps sold

Pages 83-85: Information on the quantity of post cards sold

Pages 85-87: Information on the quantity of envelopes, wrappers, and telegraph stamps sold

Between pages 88 and 89: Fold-out page detailing the exact numbers printed

Pages 88-89: Manufacturing costs for official urgent service stamps

Pages 90-93 and 95: Current letter and parcel post rates for domestic and Universal Postal Union (UPU) mail

Page 99: Overview of the states belonging to the UPU

Reprints of stamps, etc.

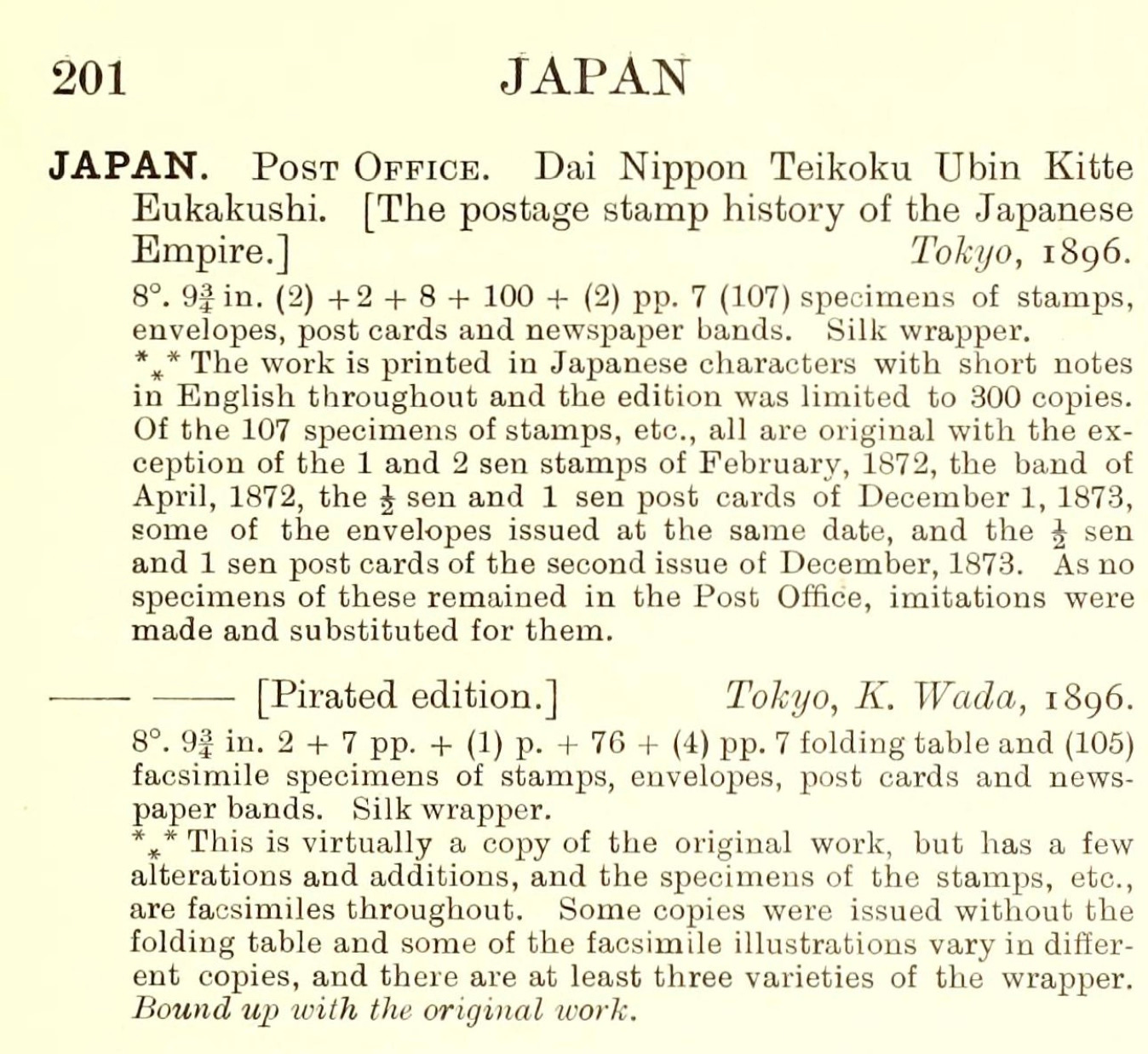

Bibliotheca Lindesiana Vol VII, popularly known as the Crawford Catalogue, records Enkakushi on column 201 (Figure 9) thereby giving it the status of “philatelic literature”. As per the catalogue, read with the 1926 supplement, the book measures 9¾ inches and has (2) + 2 + 8 + 100 + (2) pp. Those who prefer the metric system can find comfort with the measurement of 178 x 248 mm.

Of the 107 specimens (59 postage stamps, 32 postcards and envelopes, four wrappers, 10 telegraph stamps, and two urgent-message stamps), all are originals but for the following eight which are reprints:

1 and 2 sen ‘dragon’ stamps of February 1872 (on page 3 of the book) (see Figure 4)

2½ rin band or wrapper of April 1872 (on page 4)

½ and 1 sen red-border postcards of December 1873 (on pages 9-10) (see Figure 5 for the former)

2 sen Japanese-style envelope of the same date (on page 11) (see Figure 5)

½ and 1 sen single-color postcards of the second issue of December 1873 (on pages 17-18)

(Note: 10 rin = 1 sen and 100 sen = 1 yen)

Official reprints of the above had to be made since even at this early period, as originals were no longer available in enough quantity for the copies produced. These reprints were made from new plates of better quality than the original plates, and hence are much clearer than the originals.

Copies Printed

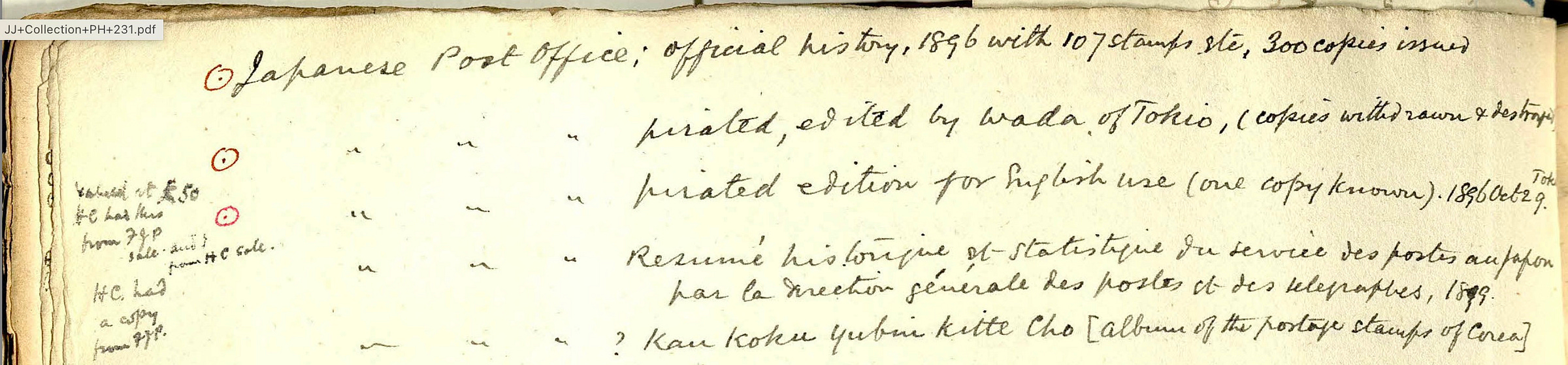

Two of the earliest articles on the Enkakushi published in 1897 in the German Deutsche Briefmarken-Zeitung and the English Filatelic Facts and Fallacies (see notes) say that 300 copies of the book were printed.

The Crawford Catalogue too asserts that “the edition was limited to 300 copies” (Figure 9). Given its compiler Edward Bacon’s reputation as a meticulous philatelist who was also very well versed with Japanese stamps and stationery, it is almost impossible to believe that he would have recorded an incorrect number.8

The other figure that is most often mentioned is 500. Japanese Philately is one of Japanese philately’s premier journals; across its issues spanning decades, one almost invariably sees this number at places where the Enkakushi is being discussed.

More recently, in his 2004 monograph, The Tourist Sheets and Booklets of Japan, Ron Casey has a different take: he says that 500 were produced but only 300 distributed.

Earthquake of 1923

Another statement that one frequently sees is that many copies of the Enkakushi, as many as half of the print run, were destroyed in the Great Kantō earthquake and fire of September 1, 1923, at that time considered to be the worst natural disaster to strike Japan. These would have been the undistributed ones stored at the Communications Ministry or owned by Japanese residents.

While it is difficult to verify this statement, logic dictates we take it with a pinch of salt. It is improbable that so many copies would have been lying undistributed for more than 25 years down the line, unless one accepts Casey’s view that 200 copies were not distributed, and were destroyed in the disaster. As early as September 1897, the magazine Filatelic Facts and Fallacies reported that “only four or five” copies were left with the post office.

Wada’s Pirated Edition(s)

Within a few months, on 29 October 1896, a pirated edition, a “tolerably good imitation” as the Williams brothers declared it to be, was published by the notorious Wada Kotarō of Tokyo (Figure 10).

Wada, the forger

Wada was the premier forger of Japanese classic stamps. He has been reported to have been a bookseller but according to his son, Wada Isaburō, who was born in 1887, his father was a dealer in curios and antiques who started his stamp business in 1885 (though there are reasons to believe that he was active from as early as 1880). Unfortunately, there exists little personal information about the man, not even his birth or death dates nor a photograph of him.

From the 1880s until he stopped marketing forgeries in 1911, retiring a year later, Wada prepared and sold millions of “good to excellent” counterfeits, some of which even deceived seasoned Japanese specialists such as Edward Denny Bacon and A. M. Tracey Woodward.

How could he have carried on his business for so long without falling foul of the law? Theoretically, imitation stamps were to marked as such. Wada used tiny (1 mm high) Japanese characters reading “sankō” (meaning reference) or “mozō” (facsimile). But he also found ways around, such as applying bogus cancellations in such a way that they obliterated these characters. Later, he stopped applying these marks altogether thumbing his nose at the authorities, who ignored these shenanigans. It was only about 1905 that they cracked the whip. Still, Wada continued his operations in secret for a few more years before, it is said, his copper plates were confiscated by a certain authority. This may have led to the stoppage of his business and his retirement.

There is little doubt that Wada’s stamps were mainly intended to deceive collectors, especially foreigners. He pioneered affixing series of his forgeries to attractive sheets with ornamental borders for sale and distribution in Japanese ports which saw substantial footfall of tourists; these are the so-called “tourist sheets”. Due to his prolific output, it is estimated that that in any general collection of classic Japanese stamps, forgeries outnumber genuine copies by a ratio of 10 to 1.9

Wada’s Enkakushi

In the preface of his edition dated October 29, 1896 (Figure 11; a full translation appears in Appendix 2), Wada justifies why he decided to come out with his work. He complains that foreigners are mopping up Japan’s postage stamps and that in a few years, Japanese people may fit it difficult to obtain the stamps of their country. If that happens, the Japanese would not be able to make studies of artistic development and progress. To avoid such a possibility, he has made fascimiles of stamps and printed the book for wide distribution.

It is more likely that Wada’s intentions were not so noble and that he made his pirated edition(s) in order to not only mass-market his own forgeries but also to prove that he could reproduce anything the postal service could create.

It is believed that most of these copies was confiscated and burnt by the police. However, a few must have already been sold by then and they thus escaped destruction. This, and the fact that Wada made only a few copies, means that the pirated edition is rarer than the official one. The Williamses believed that “probably no more than half a dozen” survived while that great philatelic literature collector, Frank Bellamy, knew of four including one in stiff boards (Figure 18). Even if one adds copies that might have been in Japanese hands and that westerners were not aware of, the total number is still likely to be less than 10.

Varieties of Wada’s Enkakushi

According to the Crawford Catalogue (Figure 9), three different varieties of the wrapper of Wada’s Enkakushi are known to exist.

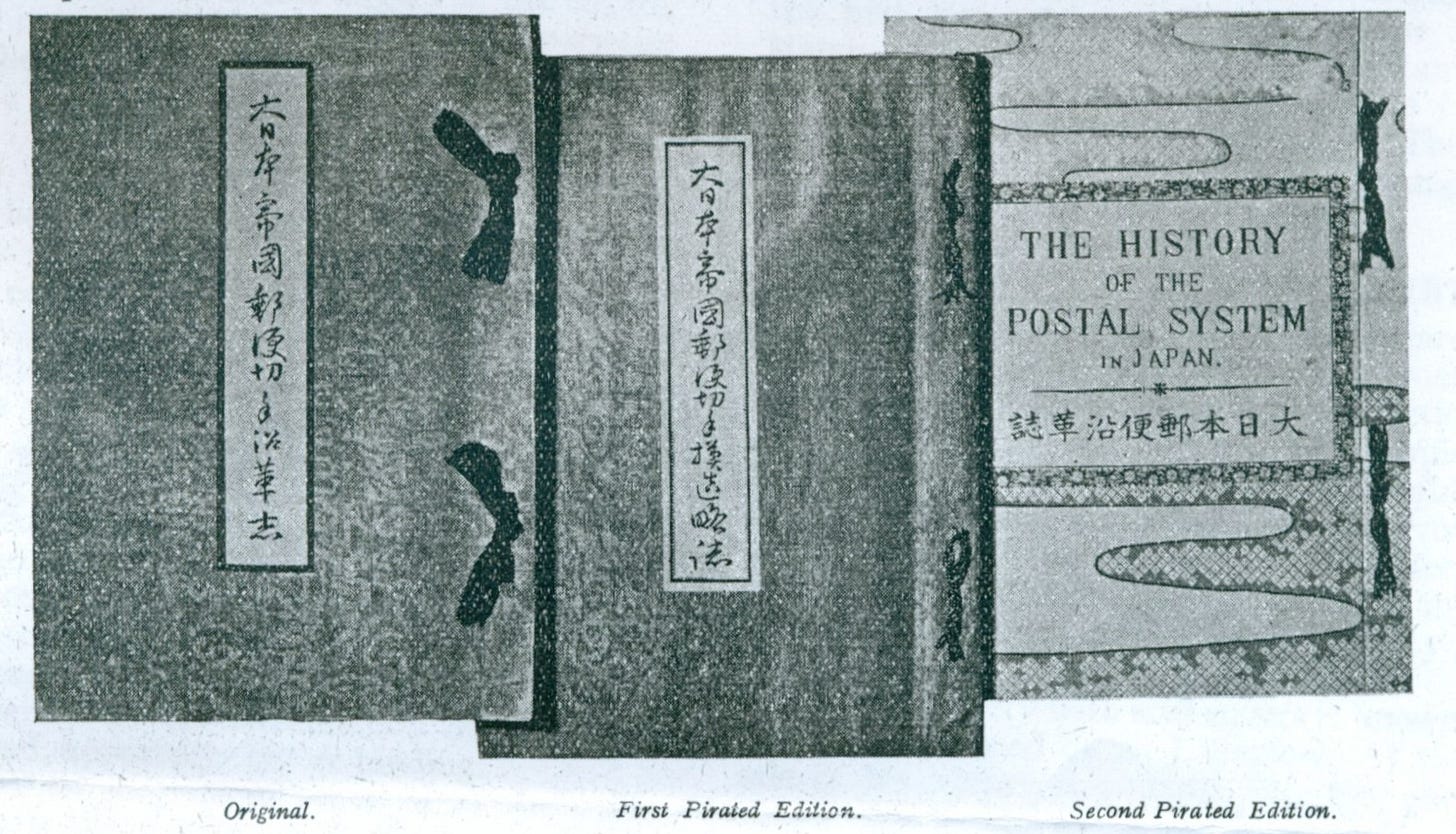

Dai Nippon Teikoku Yūbin Kitte Mozō Ryakushi (Imitation Abridged History of the Postage Stamps of the Great Japanese Empire): This “first pirated edition”, as the Williams brothers call it, is just a bit larger than the original at 9⅞ inches,10 the covers are of a slightly deeper shade of gold silk than the original, and the binding is in lilac silk threads (see Figure 10). It is printed on white wove paper.

The book has fewer pages than the original since it seems to have done away with the statistical tables. It does have the fold-out page, as in the original, tabulating the numbers of stamps printed; this is inserted at the back next to the cover. Pages have less text and some of the text is typeset differently (Figure 12).

One of the introductory pages has been replaced by a page bearing four illustrations. The first page in English is the ninth by count, unlike in the original where it is the 11th. Near the end of the book, particulars and illustrations of the Russo-Japanese War stamps are included; these stamps were issued in August 1896, months after the publication of the official edition.

All the specimens in it are either forgeries or black and white imitations totaling 105 in number. The forgeries by Wada were not specially made for this book but were ones already circulating in the market. In a fine example of collaboration amongst rouges, some uncancelled Kobon and postal stationery included it were made by another forger, Maeda Kihei, and sold by Kamigataya (Kamigata company). Finally, the work was priced at 1 yen 50 sen.

The History of the Postal System in Japan / Dai Nippon Yūbin Enkakushi: The “second pirated edition” is extremely rare, with only one copy known! It was probably made keeping the European market in mind. The cover of this is buff cardboard, printed with a Japanese check design in pink and white and red and white. In the center of this cover is the title in Japanese and English, which is enclosed in a rectangle surrounded by a floral design. The book is bound with purple silk (Figure 13).

This work differs from the first pirated edition in that it contains 84 pages and 101 illustrations, the page with four illustrations at the end of the introduction having been omitted presumably before binding. The first page in English is the seventh by count. Several pages have been bound in the wrong order. In some cases, envelope cut-outs and used common stamps were pasted over the black and white stuck-down illustrations. The printer’s name and address, i.e. Takahashi Tomokichi of 7 Mizuyacho, Kyobashi Ku, Tokio, appears on the inside back cover of the book; the publisher’s name and address has been erased.

Dai Nippon Teikoku Yūbin Kitte Mozō Ryakushi (Imitation History of the Postage Stamps of the Great Japanese Empire): It was initially thought that the pirated edition was titled thus. However, the copy in Figure 10 and Figure 13 (middle) are both titled Dai Nippon Teikoku Yūbin Kitte Mozō Ryakushi. In his December 1976 article, Dr. Spaulding (p.309) talks about various early Japanese philatelic publications. He writes:

Dai Nippon Teikoku yūbin kitte mozō enkakushi [Imitation History of the Postage Stamps of the Great Japanese Empire], Tokyo: Wada Kotarō (price 1 yen 50 sen). This forged edition of the government presentation book (that is, an unauthorized reproduction of the text, illustrated with forged rather than genuine stamps) is cited by Japanese sources (such as F26-27) with title as shown above, but Dr. V. E. Tyler has found it with the title Dai Nippon Teikoku yūbin kitte mozō ryakushi [Imitation Abridged History of the Postage Stamps of the Great Japanese Empire], and we suspect the listing in Japanese sources is incorrect.

If it exists, how the Dai Nippon Teikoku Yūbin Kitte Mozō Enkakushi varies from the ones above, especially the “first pirated edition” is not known. Is it only with respect to the title or are there more points of difference?

Valuation

As mentioned before, Enkakushi was never intended to be sold. However, over time, copies have come into the philatelic market and have realized healthy to fantastic prices. As far back as the 1950s, copies were selling for between US$ 50 and $150.

Many justifications can be made for its high valuation. It was beautifully produced. It uses unused examples of genuine and official reprinted stamps, some of which are scarce and command good value. It is highly sought by both philatelic literature and stamps collectors. And obviously because it is hard to find. Though 300 were produced, just a small percentage of them seem to have survived intact. The ones that went to non-philatelists may not have been preserved since their owners did not realize their worth. Further, over time, many are likely to have been vandalized for their stamps. A search of the Global Philatelic Library’s website shows that only the British Library (holding the Crawford Library) and the Collectors Club of New York possess both the original and pirated editions.

Recent Sales

An inquiry with four of the long-standing philatelic literature dealers in the world today (all of whom have I have interviewed and whose interviews have been published in the pages of the Philatelic Literature Review over the last few years) resulted in the feedback that none of them have handled this book before! One of them mentioned that since it appealed not just to bibliophiles but to philatelists as well, it was more likely to appear in stamp auctions rather than pass through the hands of a literature dealer.

Some recent stamp auction realizations of the original edition follow; this is not an exhaustive list and is only meant to give a flavor.

In one Corinphila of Zurich auction of September 2013 (sale no. 182), lot 237 with a start price of CHF 10,000, sold for Swiss Francs (CHF) 21,000 (CHF 25,200 including 20% buyer’s premium or US$ 27,845 at the then prevailing exchange rate).

A Dutch auction by Rietdijk took place on November 11, 2014 (this is the auction talked about in the “Housing” paragraph above). A copy from the library of Dutch collector and author, Alko van der Wiel, was on sale. It was lot 4090 and it sold for Euros (EUR) 6,200 (EUR 7,564 including 22% buyer’s premium or US$ 9,420).

A January 12, 2020 sale of Spink China in Hong Kong saw the book appear as lot 6468. Estimated at Hong Kong Dollars (HKD) 80-100,000, it sold for HKD 90,000 (HKD 108,000 including 20% premium or US$ 13,900).

In another Corinphila auction of November 28, 2022 (no. 291), lot 1536 had a high start price of CHF 10,000. It sold at that price itself i.e. CHF 10,000 (12,200 including 22% premium or US$ 13,025).

In July 2024, two apparently complete copies came to the market in quick succession (they were responsible for invoking my curiosity and making me write this).

The first was auctioned by the Barcelona-based auction firm, Soler y Llach, on July 10 (see Figure 1). Appearing as lot 1305, it appears to be a beautifully preserved copy. Estimated at 4,000 euros, it sold for 8,000 euros (9,760 euros including the 22% buyer’s premium or US$ 10,570). Figure 14 shows the dark green box in which this copy is housed. It was made by a later owner and is not the original.

Another copy appeared a week later on July 17, 2024 in Siegel Auctions of New York (Figure 14). This was lot 5650 and was estimated at US$ 4,000-5,000. It split the range selling for US$ 4,500 (US$ 5,310 including 18% premium). Or, at current exchange rates, half the price that the Soler y Llach copy fetched.

Coming to Wada’s pirated Enkakushi, given its fewer surviving numbers, it should logically sell for far higher than the original. But logic and reasoning do not always hold good in the real world; what sets prices is desirability.

In the Corinphila of Zurich auction of September 2013, lot 238 with a Wada forgery had a start price of just 1,000 Swiss francs. It sold for 3,400 francs (4,080 francs including 20% buyer’s premium or US$ 4,510 at the then prevailing exchange rate). The same sale had seen the original go for six times the price (see above)!

In the same auction firm’s sale of November 28, 2022, another Wada production (see Figure 10) appeared as lot 1537 with the same low-ball start price of 1,000 francs. It went for a modest 5,500 francs (6,710 francs or US$ 7,163 all-in); the same sale saw the original fetch almost twice the price.

The rarest of them all is the pirated version with bilingual covers (second pirated edition) bound in stiff cards, of which only one is known. It was once owned by Frank Jukes Peplow (Figure 16), not just a bibliophile but also a Japanese specialist.11

Peplow had a correspondent in Japan, from whom he acquired this copy, probably soon after its publication. When Glendining & Co. of London sold Peplow’s library on March 8, 1917, lot no. 110 containing this was purchased by Herbert Clark (1880-?) for £21 (incidentally, lot 108 was the original and sold for £7-5s and lot 109 was Wada’s first pirated edition and fetched £11-10s; one sale in which the pirated editions trumped the original).

A few years later, Clark went bankrupt, and his library was auctioned by H.R. Harmer on February 18-19, 1924. The copy sold for £15-10s to one of the greatest philatelic bibliophiles, Frank Arthur Bellamy (1863-1936) (Figure 17).

Bellamy’s philatelic library was then considered to be the largest in the world. After his death, the whole of his library was bought in 1938 by the philatelic literature dealer, Albert Henry Harris (1885-1945).

Harris soon started breaking down the library for resale. He advertised this copy at £5012 in the April 29, 1938 issue of his journal, Philatelic Magazine (Figure 18). Unfortunately, its current whereabouts is unknown.

Acknowledgements: I do not have copies, physical or digital, of either the original or the pirated editions. So, I have had to take the assistance of many. This article has benefited from the cooperation of both Japanese philatelists as well as philatelic bibliophiles.

I found a lot of information in Japanese Philately, journal of the US-based International Society for Japanese Philately (ISJP). I would like to thank the late Dr. Robert M. Spaulding (1923-2013), renowned researcher, writer, and long-time editor of the journal; without his writings, importantly for me in English, this article would have been much poorer in its content. Ken Kamholz, publisher of Japanese Philately and secretary & treasurer, ISJP provided me with all the relevant scans from the journal; initially, I asked for only four pages, but he immediately sent me more than 100! Ken Bryson, current editor of Japanese Philately, translated the original work’s and the Wada edition’s preface. He also helped get feedback from Lois Evans-de Violini, a doyenne of Japanese philately.

Amongst bibliophiles, Jan Vellekoop, Wolfgang Maassen, and Mårten Sundberg helped me by references to and scans of past literature on this topic. Feedback is always welcome; please email them to abbh [at] hotmail.com.

Appendix 1: Translation of the Preface of the Original Enkakushi

1. This volume sets forth the historical progress of the postage stamps, postal cards, stamped envelopes and wrappers, as well as official urgent service stamps and telegraph stamps, of the Japanese Empire from their outset in March of the year Meiji 5* up to March of Meiji 27.

2. This volume synopsizes information from official records preserved at the [Communications] Department and includes actual specimens of all materials from their time of issue. However, facsimiles have been produced of the 1 sen and 2 sen stamps issued in February of [Meiji] 5, wrappers issued in April of Meiji 5, and two types each of ½ sen and 1 sen postal cards as well as the long-format 2 sen stamped envelope all issued in December of Meiji 6, due to lack of sufficient supplies.

3. As this volume compiles [issues] by date and classifies by type, a table is first presented to provide an overview of all categories.

[* Author’s Note: In the lunisolar calendar, this date corresponds to April 1871. The Gregorian calendar was adopted on December 3, Meiji 5 (lunisolar), corresponding to January 1, 1873. Note that the year 1868 is referred to as Meiji 1.]

Appendix 2: Translation of the Preface of Wada’s Pirated Edition

The reason for this publication, comprising reproductions of all postage stamps, postal cards, and stamped envelopes that have been issued from the beginning of postal services in this country until recent years, is none other than this: The custom in the western countries of collecting old and new postage stamps and the like, and mounting them into albums for enjoyment, is no different from the way that persons in our own country take pleasure in collecting antiquities, works of art and calligraphy, and the like; hence there are many who seek to purchase such items even at high cost. Why would this be?

One reason for amassing such collections might be to demonstrate to others how one has connected widely with persons of other countries, or has participated actively in commerce; again, it may be to engage with others to compare and evaluate the artistic qualities of their collections, or as a means to study how the state of human learning has progressed through the ages. If so, these are not mere curiosities; rather, they are essential as useful reference materials.

At this time, foreigners are eagerly collecting our country’s old postage stamps; given this state of affairs, even our people may find it difficult to obtain the stamps of their own country in not too many years. In such circumstances, it may well become impossible to make comparative studies of artistic development and progress without any reproductions of appearance and form, much less the original articles. Finding this to be a regrettable prospect, the editor has caused facsimiles as shown in this illustration to be etched and printed for wide distribution to persons of shared interests.

October, Meiji 29 [1896] The Editor

[Author’s Note: The full translation of the preface, courtesy of Ken Bryson, is given below. He says that the Japanese text is rather quaint, and that he has taken some liberties to simplify the language.]

References

Amrhein, Manfred. Philatelic Literature: A History and a Select Bibliography from 1861 to 1991 Volume 3 The Middle East - Africa - The Far East. Vol. 3. 4 vols. San Jose, Costa Rica: The Author, 2001.

Anon. “Dai Nippon Teikoku Ubin Kitte Eukakushi.” Filatelic Facts and Fallacies V no. 12 whole no. 60 (September 1897): 147-151

(Bacon, Sir Edward Denny). Bibliotheca Lindesiana Vol VII: A Bibliography of the Writings General Special and Periodical Forming the Literature of Philately. Aberdeen: University Press, 1911.

Bacon, Sir E[dward]. D[enny]. Supplement to the Catalogue of the Philatelic Library of The Earl of Crawford, K.T. Published 1911. London: The Philatelic Literature Society, 1926.

Bungerz Alexander. Die Versteigerung der Bibliothek von Herbert Clark (=The Auction of Herbert Clark’s Library), Berlin: Der Philatelistische Bücherwurm, 1924

Casey, Ron. The Tourist Sheets and Booklets of Japan. International Society for Japanese Philately, Inc., 2004.

———. “Newly Discovered Wada Tourist Sheet for Forged Wrappers.” Japanese Philately 61 no. 1 whole no. XXX (April 2006): 4-10

Maassen, Wolfgang, and Vincent Schouberechts. Milestones of the Philatelic Literature of the 19th Century / Les Jalons de La Littérature Philatélique Au XIXe Siécle. Monaco: le Musée des Timbres et des Monnaies de Monaco (=Club de Monte-Carlo), 2013.

Metzelaar, Willem, and Varro E. Tyler, “Forgeries and Imitations of the Dragon Stamps of Japan.” Japanese Philately. 26 no. 1 whole no. 181 part 2 (February 1971)

Ohrt, Lieutenant. “Die Postwertzeichen Japans.” Deutsche Briefmarken-Zeitung VIII no. 3 (March 11, 1897): 41-43

———. “Die Postwertzeichen Japans.” Deutsche Briefmarken-Zeitung VIII no. 6 (June 12, 1897): 90-94

———. “Die Postwertzeichen Japans.” Deutsche Briefmarken-Zeitung VIII no. 9 (September 18, 1897): 148-154

Peplow, F. J. “My Philatelic Library - a Retrospect.” The Journal of the Philatelic Literature Society X no. 4 (October 1917): 47-50

Spaulding, Robert M. “A Rich Heritage from the Snowy Lake.” Japanese Philately 27 no. 2 whole no. 178 (April 1972): 43-61

———. “Postcard Centenary.” Japanese Philately 28 no. 5 whole no. 187 (October 1973): 207-231

———. “Japan’s Earliest.” Japanese Philately 28 no. 6 whole no. 188 (December 1973): 305, 308-309

———. “A Pioneer in Japanese Philately: Part One - Edme Gallois before 1950” Japanese Philately 49 no. 4 whole no. XXX (August 1994): 162-XXX

(Spaulding, Robert M.) “Stamped Envelopes 1873-74. Quantities Sold.” Japanese Philately 27 no. 6 whole no. 182 (December 1972): 245

——— “Enkakushi and Enkakuchō.” Japanese Philately 47 no. 4 whole no. XXX (October 1992): 170

Tyler, Varro E. Philatelic Forgers: Their Lives and Works. 2nd ed. Sidney, Ohio: Linn’s Stamp News, 1991.

Williams, L.N. and M. Williams. “ “The Postage Stamp History of the Japanese Empire.” Philatelic Magazine. (October 14, 1938)

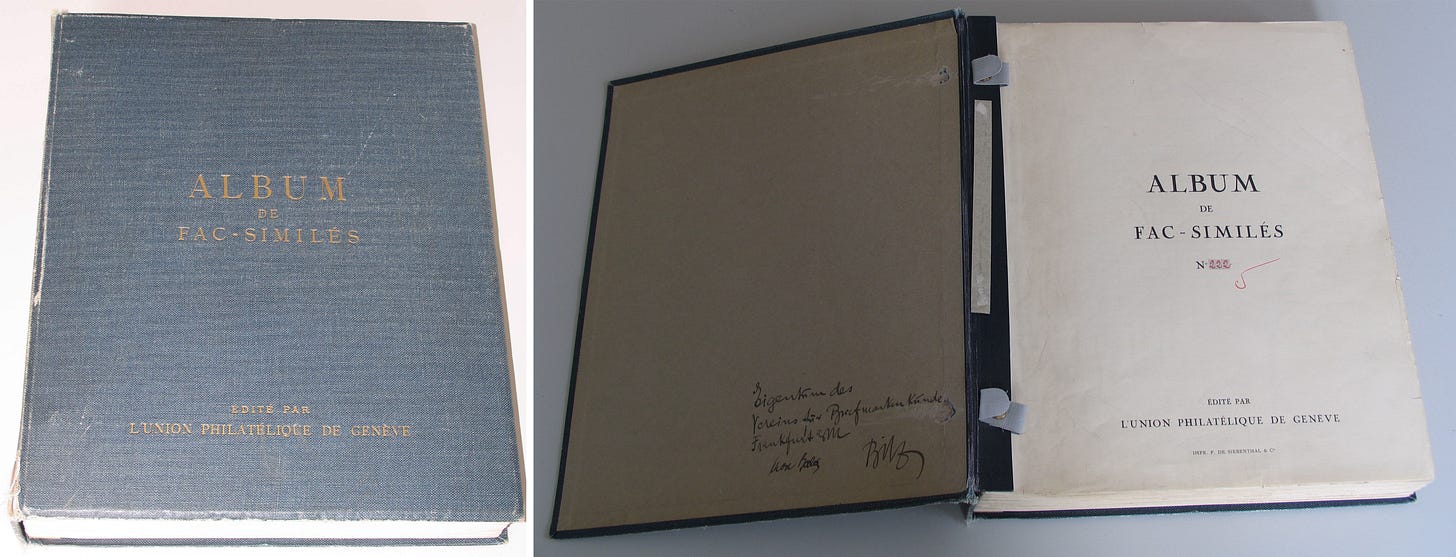

Another would be the 1928 “Fournier album” of forgeries (Album de Fac-similes)(Figure A).

François Fournier (1846-1917) was a stamp forger based in Geneva. His stock of forgeries was bought by L’Union Philatélique de Genève (Philatelic Union of Geneva) who, in 1928, produced 480 albums containing his works.

The Crawford Catalogue mentions the publisher as the Japanese Post Office. An online record of this work in the Crawford Library in the British Library says, “Japan Ministry of Postal Services”.

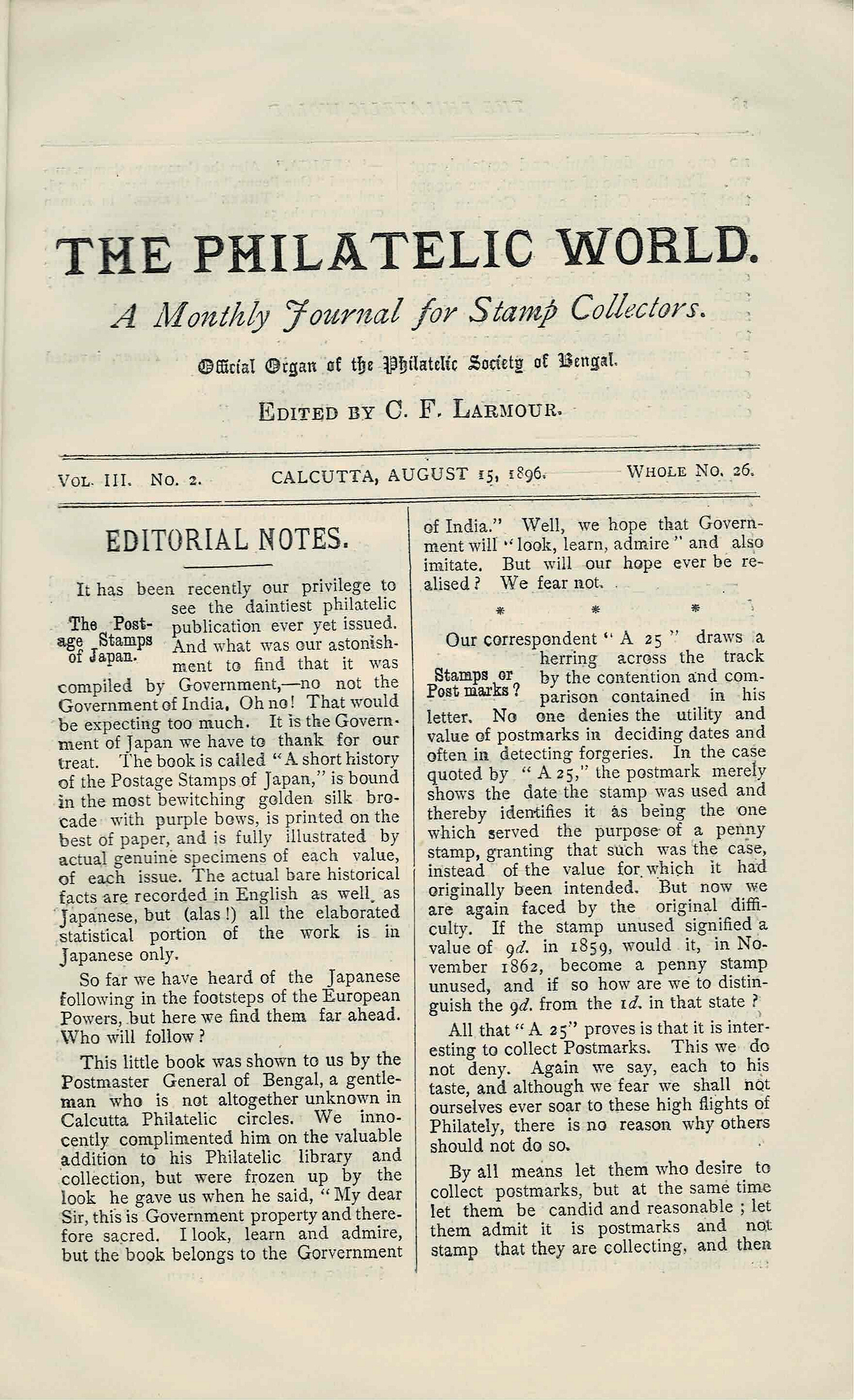

In a few months post publication, news about it reached the philatelic press. Perhaps the first to note it was the Calcutta-based The Philatelic World (Figure B).

In its August 15, 1896 issue, the editor, C.F. Larmour, wrote:

It has been recently our privilege to see the daintiest philatelic publication ever yet issued…It is the Government of Japan we have to thank for our treat. The book is called “A short history of the Postage Stamps of Japan,” is bound in the most bewitching golden silk brocade with purple bows, is printed on the best of paper, and is fully illustrated by actual genuine specimens of each value, of each issue. The actual bare historical facts are recorded in English as well as Japanese, but (alas!) all the elaborated statistical portion of the work is in Japanese only.

Japan used the lunisolar calendar until December 31, 1872 before switching to the Gregorian one. As per the lunisolar calendar, Japan’s first stamps were issued on March 1, 1871. The preface of Enkakushi mentions this latter date.

In Japan, the family name or surname is mentioned first. Hence, Hibata Shōtarō’s surname is Hibata and given name is Shōtarō.

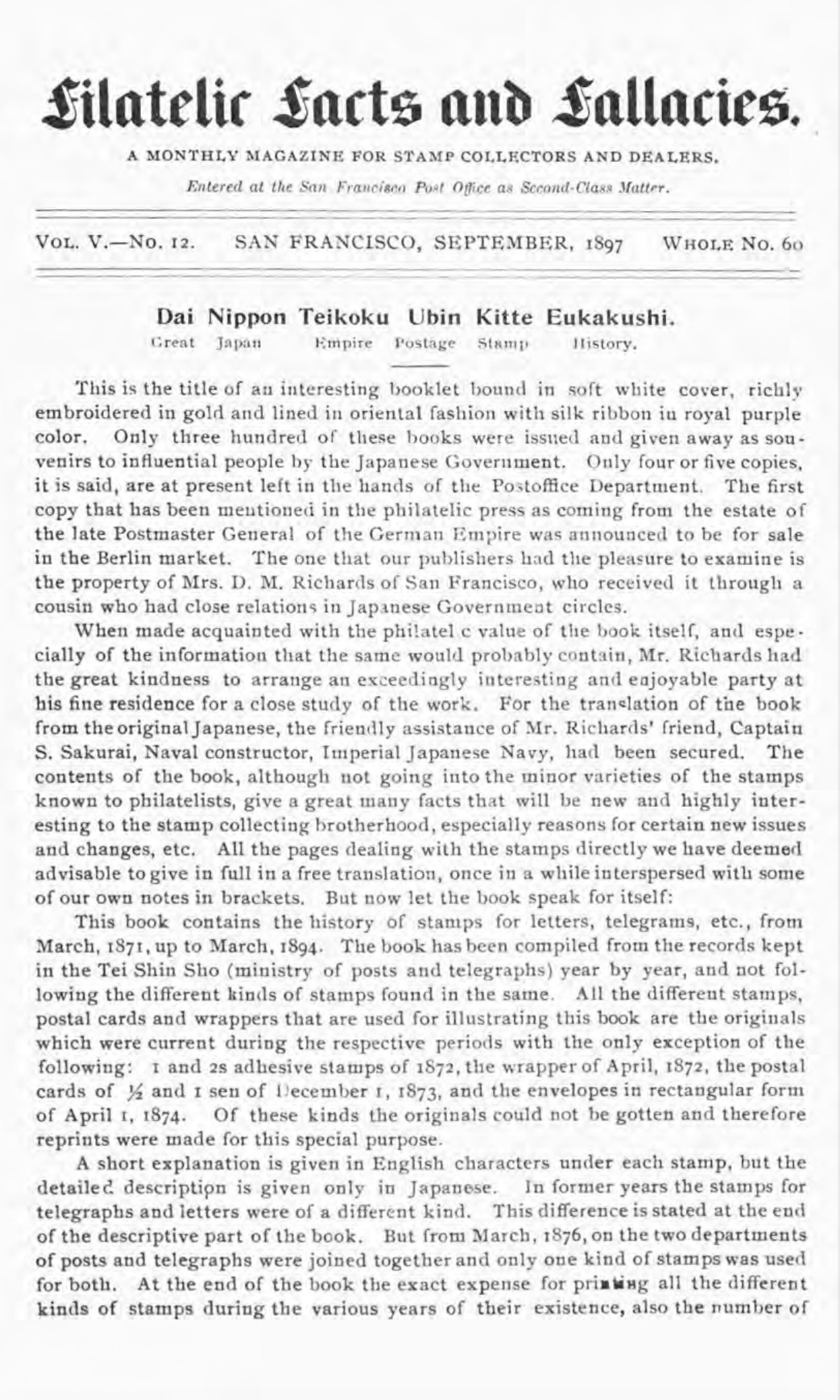

Perhaps the first translation of the Japanese text and tables was made by Lieutenant Wilhelm Johann Paul Ohrt (1867-1944) in a series of three articles in the German journal Deutsche Briefmarken-Zeitung (Figure C).

An English translation of the text (though not of the statistical tables containing “small Japanese numbers running up to the thousands and millions”) was published in the September 1897 issue of the Filatelic Facts and Fallacies (Figure D).

The book used for the translation was of one Mrs. D. M. Richards of San Fransisco, who received it through a cousin who had close relations in the Japanese government. The translation was done with the assistance of Mr. Richard’s friend, Captain S. Sakurai, naval constructor, Imperial Japanese Navy.

The relevant pages can be downloaded from the link below.

In a small piece published in the October 1992 issue of Japanese Philately titled “Enkakushi and Enkakuchō”, the writer mentions that “Japanese stamp catalogs today assign major numbers to 37 stamps in the 1872-76 Cherry Blossom series.” Lois Evans-de Violini says that there has always been a difference between the philatelic viewpoint of how many major varieties there were in those stamps and the official viewpoint. At one time Scott said there were 39 different types; now they list 40. Meanwhile the Sakura 2020 catalog lists 43.

Sir Edward Denny Bacon (1860-1938), the compiler of the Crawford Catalogue, was also a noted collector of Japanese stamps. The January 1897 issue of The Philatelic Record contains an interview with him wherein he mentions that he built up a collection of the stamps, envelopes, and postcards of Japan over 10 years (likely from the early 1880s to the early 1890s) and that “it was pronounced the finest lot of Japan ever got together.” He sold it for a four-figure sum shortly after the death of his friend and the great collector, Thomas Keay Tapling (1855-1891). In fact, Bacon contemplated giving up philately altogether after Tapling’s death, but thankfully he did not.

This statement was made by Tyler in the first edition of his Philatelic Forgers published in 1976 and repeated in the second edition published in 1991. Lois Evans-de Violini says that this statement still holds true of any general collection that she has seen recently; but she notes that there are a lot fewer general collections than there used to be.

In the Crawford Catalogue, the size of the original and pirated edition is both measured as 9¾ inches. However, the Williams brothers, likely using Bellamy’s copy, size the first pirated work at 9⅞ inches.

In 1910, Peplow published Plates of the Stamps of Japan 1871-76, One Hundred and Nine Sheets Reproduced in Collotype. This was produced in an edition of 25 only and was available by subscription only. It contained photographic plates of 107 (not 109) sheets of stamps issued between 1871 and 1876, together with 14 uncut pages. This is yet another extremely rare item in the annals of Japanese philatelic bibliography.

Harris incorrectly mentions that Bellamy purchased the book for £50. So do the Williams brothers who mention in their 1938 article that it passed to Bellamy “for more than double that sum”, the sum being £21 paid by Clark in 1917.

In 1924, very soon after the sale of Clark’s library, the German bibliophile, Alexander Bungerz (1874-1931), produced a 17-page pamphlet on the sale titled Die Versteigerung der Bibliothek von Herbert Clark. In it, Bungerz mentions that the work realized £15-10s. This combined with Bellamy’s noting in his catalog that he “valued” the book at £50 makes me conclude that Bellamy did not pay £50 for it but just thought that it should be worth so much. Harris and the Williams’, likely working based on Bellamy’s subsequent notes, were led into believing that this was the price paid by the latter.