Frank Bellamy and the Catalog of his Philatelic Library

A long-lost philatelic bibliography discovered

This article was first published as “Frank Bellamy and the Cataog of his Philatelic Library” Philatelic Literature Review 73 no. 1 whole no. 281 (First Quarter 2024). It has been lightly edited with additional images for publication online.

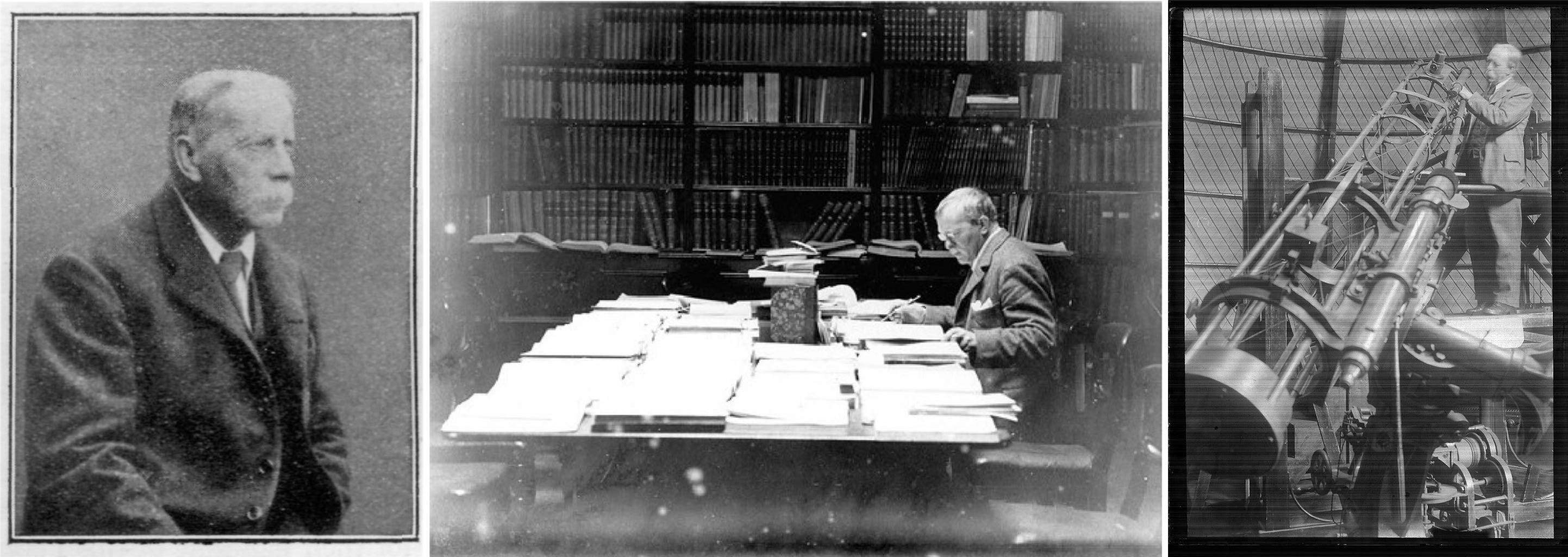

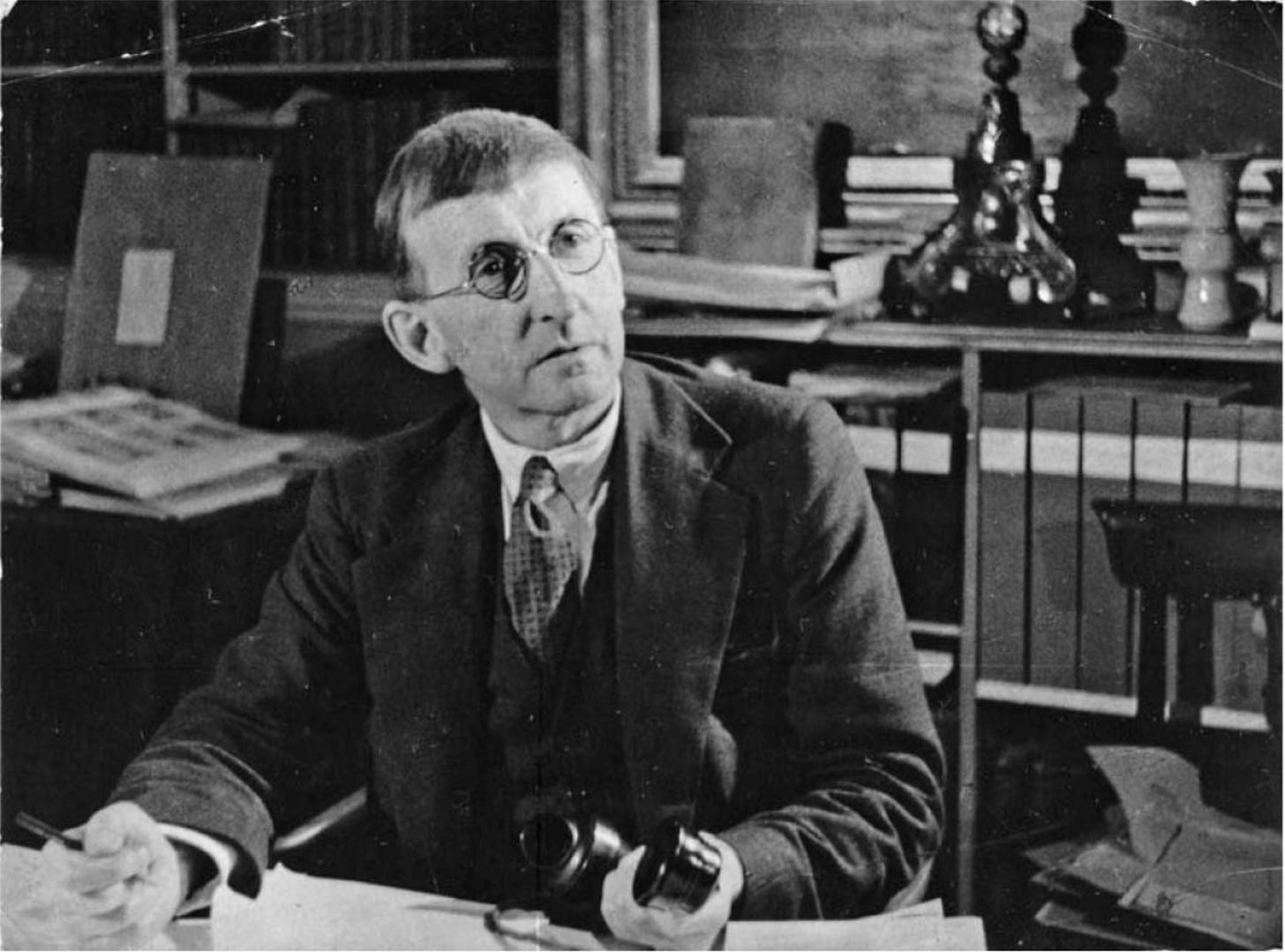

Frank Arthur Bellamy (1863-1936) (Figure 1) was one of the greatest philatelic literature collectors of all time. After the library of the Earl of Crawford1 was bequeathed to the British Museum (and now in the British Library) in 1913, Bellamy's was considered the largest private philatelic library in the world until its sale in 1938. The article will discuss Bellamy and importantly, the catalog of his library, presumed to have been lost but rediscovered now.

Bellamy, the Astronomer

Bellamy was born in Oxford on October 17, 1863, as the seventh and last child of a college butler and master bookbinder (perhaps one of the reasons for his love of books). In 1881, he started his astronomical career as an assistant at Radcliffe Observatory at Oxford; his two elder brothers had held that post before him. 11 years later, he joined the University Observatory at Oxford.

Bellamy devoted 46 years to the Astrographic Catalogue, the first international scheme to use photography to catalog stars in both hemispheres.

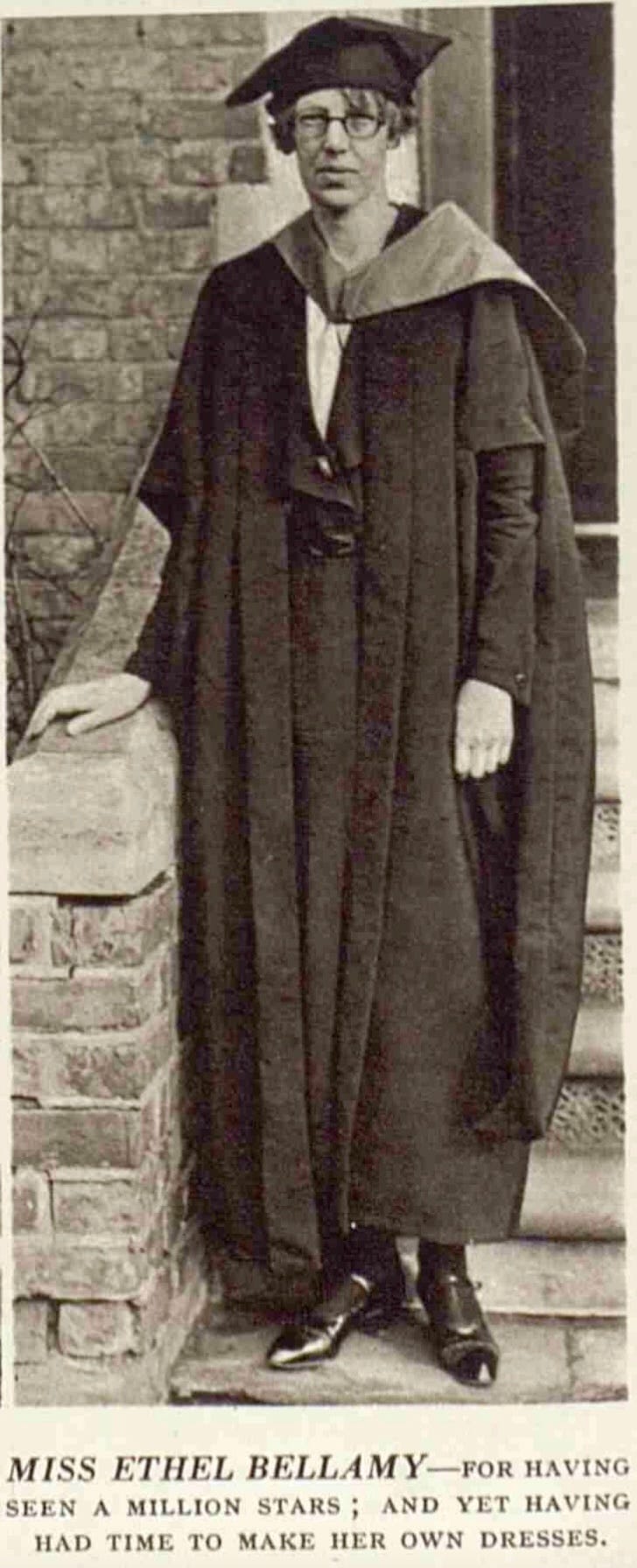

By 1928, Bellamy, along with his niece, Ethel Bellamy (Figure 2),2 had catalogued some 1 million stars. Ethel and her invalid sister Edith, daughters of Frank’s eldest brother, Montague, lived with Bellamy at various residences: 4 St Bernard’s Road, 28 Polstead Road, and finally 2 Winchester Road (Figure 3).

Bellamy served as acting director of the University Observatory at Oxford between November 1930 and May 1932 (Figure 1). In June 1932, the Canadian Harry Hemley Plaskett arrived as the new (and first overseas) Savilian Professor of Astronomy and director of the observatory. Soon thereafter, Bellamy developed serious differences with Plaskett on the future direction of the observatory. In the last few months of 1935 they weren’t on speaking terms. On January 30, 1936, Bellamy had a face-to-face meeting with the vice-chancellor, listed his grievances against Plaskett, and resigned his position. He died just two weeks later on February 15 aged 74.

Bellamy was a multifaceted man who contributed to the intellectual and cultural life of Oxford city. Apart from astronomy and philately, he was involved at various times in other subjects like botany, meteorology, natural history, photography, and even the sport of cricket. In 1883, he was elected as Fellow of the Royal Meteorological Society and in 1896, a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society. On January 2, 1908, Bellamy was elected as a member and Fellow of the Royal Philatelic Society London (RPSL).

Bellamy, the Philatelist

Bellamy started collecting stamps as a child of 5 years when he inherited a large box of stamps given to his eldest brother by Bulkeley Bandinel, librarian of Bodleian Library.3 His main interest lay in the Oxford and Cambridge College Messenger Stamps,4 of which he had an extensive collection. In March 1929, he read a paper and gave a display before the RPSL of these stamps.

He was author of Oxford and Cambridge College Messengers Postage Stamps, Cards, and Envelopes 1871-86 (1921) and A Concise Register of the College Messenger Postage Stamps, Envelopes, and Cards used in the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge 1871-95, together with the stamps used by the Oxford Union Society 1859-85 (1925). He also co-authored A History of the Philatelic Congress of Great Britain and a Précis of the Proceedings at the First Four Congresses held at Manchester, London, Birmingham, Margate in 1909, 1910, 1911, 1912 (1914).

Oxford Philatelic Society

Bellamy’s greatest contribution to philately was probably as a long-standing officer-bearer of the Oxford Philately Society.

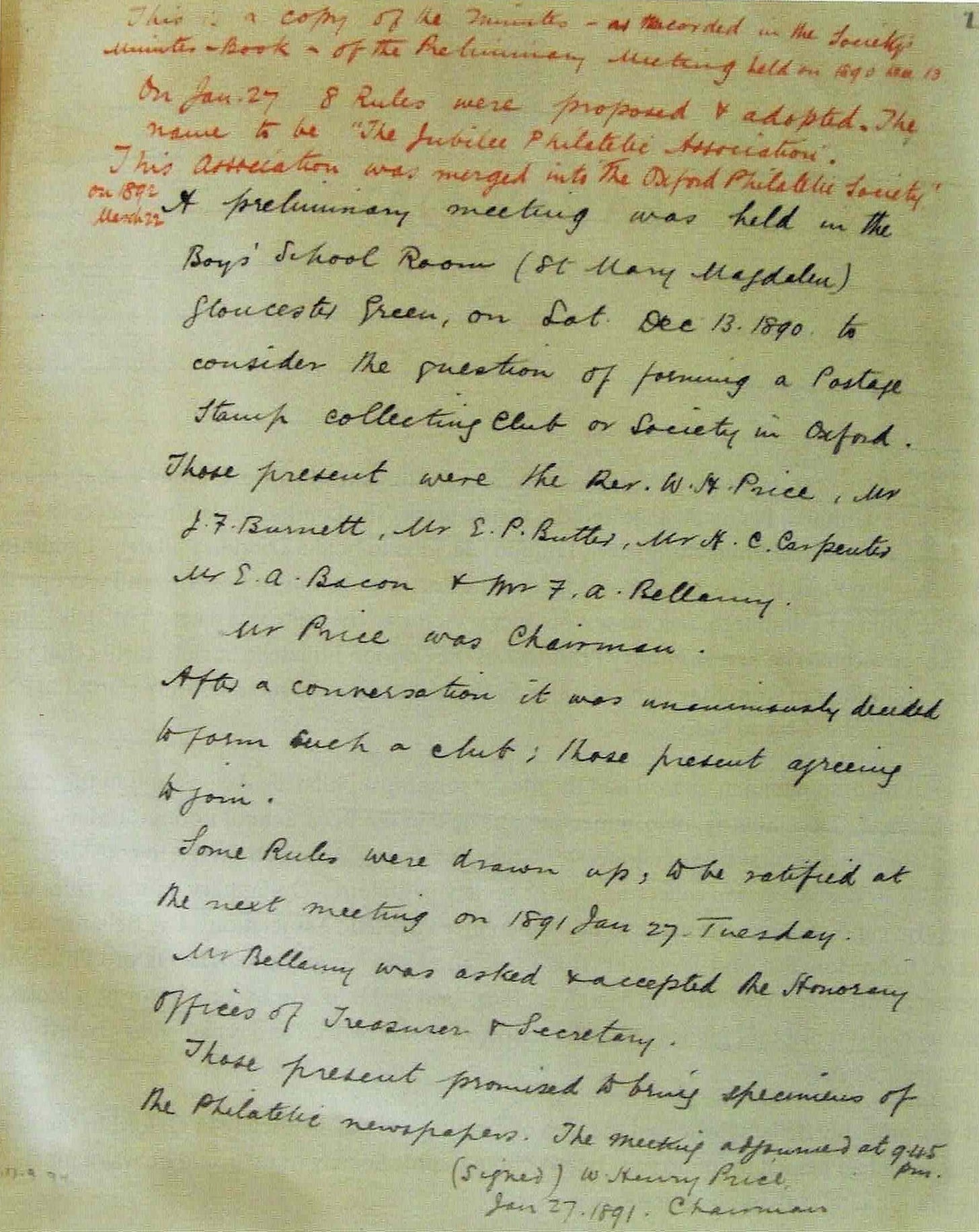

On December 13, 1890, a meeting was held in the Boys’ School Room at Gloucester Green to consider forming a “postage stamp collecting club or society in Oxford”. On January 27, 1891, The Jubilee Philatelic Association, named so since the idea of its formation came about in the 50th year of Uniform Penny Postage and Penny Black was formed. Bellamy was “asked & accepted the Honorary offices of Treasurer and Secretary.” (Figure 4).

With the fever of the jubilee abating, a year later on March 22, 1892, this association was “merged into” (Bellamy’s words, but more likely the Jubilee Philatelic Association was renamed as) the Oxford Philatelic Society (OPS). Bellamy continued in the same post until 1930 and once again from 1933 or 1934.

Bellamy was a meticulous person who was clearly dedicated to the OPS. For instance, the society’s membership was very small during the first few decades; as low as 7 in 1919 before increasing to 36 by 1929. Despite the modest status of the society in the philatelic world, Bellamy was happy to hold the dual offices of secretary and treasurer for more than 40 years. He recorded the minutes of its meetings with the same degree of detail and perfection that he would have brought to his astronomical work. In a history of the society published in Stamp Collectors’ Fortnightly of January 5, 1957, Tom Dwelly wrote:

It is felt that Mr. Bellamy’s record is unique - No man could have given more to philately of the Society to which he belonged.

At the same time, Bellamy was prickly and prone to get easily upset. For instance, in 1889 he had helped form the Oxford Photographic Society. But in 1892, he resigned on a matter of principle and refused to join its successor, the Oxford Camera Club; he joined the Banbury Photographic Club instead! Another example: in a meeting of the OPS held on March 12, 1929, Bellamy was outvoted 8-1 on an issue of increasing the yearly subscription. He put forth his intention of resigning the same day though he agreed to continue to act as the secretary and treasurer until the next Annual General Meeting in January 1930. While Captain E. Harley, who had served as president in 1927,5 succeeded him, no further meetings were held till July 25, 1933. Bellamy came back to occupy his earlier posts in either this or the next meeting held on February 13, 1934. This explains the gap of 3 or 4 years in his OPS tenure as an office-bearer. Finally, when the University of Oxford rejected his offer of donation of his collection of books and stamps (more on this later), he felt hurt enough to pen letters to newspapers and bring out a monograph on the subject. He also went back on his promise of voluntary help made to the curator of the Lewis Evans Collection of Ancient Instruments; and revoked, in his will, various gifts to the University!

Bellamy’s Philatelic Library

The “origin and formation” of Bellamy's “philatelic library arose about 1892 in his desire and intention to index philatelic publications.”6

In an article published in the November 1896 issue of The London Philatelist, he bemoaned that scarcely any of the earlier indexers had made “an attempt to give references to separate titles, contenting themselves by making a catalogue of printed books and papers relating to stamps.” He further wrote:

It seems very desirable that a full bibliography, manual, catalogue, or index of separate articles and notes published, should be collected, arranged in alphabetical order, and printed for the use of future writers and investigators on the subject of stamps, or art of stamp collecting.

Such a work I set myself two and a half years ago to accomplish, and have made fair progress, but my duties rather limit the time I can give to it. I have so far written some hundreds of slips, which are arranged as I proceed. I practically ignore the index given in each volume, but peruse every article, and if the original title is insufficiently explicit–a very common thing–I form a new one. I have now almost completed all the works I have in my possession, and take this opportunity of asking for assistance from all those who are interested in the work, and who may have books to lend me for a week or two as I require them. Every care will be taken of them, and postage paid if required.

Unfortunately, Bellamy’s index was never published and is presumed lost. He thought that his “slip-index (not yet completed)” contained possibly “a quarter of a million references”. No doubt, this is one of the greatest losses in the world of philatelic bibliography.

(However, if I were a betting man, I would say that if there is any place in the world where the index could be found, it will be in “John Johnson Collection of Printed Ephemera” held by the Bodleian Libraries.7)

That Bellamy had not completed his index isn’t a surprise; the task that he had taken upon himself was just too humongous. By the early 1900s itself, doubts were begun to be raised if Bellamy could indeed complete it. In the September 17, 1904 issue of the Pennsylvania-based The Stamp-Lovers Weekly, Frederick John Melville (1882-1940), the young but soon-to-be-great philatelist, wrote from London:

It requires no deep perception, however, to realise that the task of compiling a needed index to stampic (sic) periodicals and books is one of great magnitude, and not to be considered lightly. It must be the work of the students of our literature—and how few there are!

The one index which has been in the course of compilation in our premier University City is unlikely, in my opinion, to attain completion, for how is one man, with, naturally, other interests in life, to grapple with this very great matter. No doubt Mr. F.A. Bellamy’s work would be of the utmost value if it ever be rendered accessible and collectors cannot be too thankful for his arduous and unremunerative labours.

Coming back to Bellamy’s library. When he started his indexing project, he possessed only a few titles and was dependent on his philatelic friends in Britain and Europe to lend him such books and journals as he required. Finding this method of borrowing both expensive and troublesome, he started forming a library.

By the end of the first decade of the 1900s, Bellamy had amassed a massive library, perhaps second only to that of the Earl of Crawford.8 In 1926, it occupied about 320 linear feet of bookshelf space9 and consisted of publications in 17 or 18 languages. Some of the books that he had weren’t even in the Crawford library or “probably in any library in Europe.” Bellamy claimed that Edward Denny Bacon (1860-1938) made use of copies from Bellamy’s library to catalog certain items when compiling the supplementary volume to the Crawford Catalogue,10 which was published in 1926.11

200,000 items

The general perception is that when the University of Oxford rejected Bellamy’s offer of his vast collection, his library consisted of 200,000 books. This is incorrect. Bellamy himself thought that his collection contained “200,000 separate items” (Bellamy 1926, p.2), which included stamps, and not 200,000 items of literature alone. According to him, his gift to Oxford would have comprised of the following:

Library on Postal History (1633-1925), beyond 75,000 items12

Oxford and Cambridge College Messenger Stamps, 2,500 items

Great Britain Postage Stamps, beyond 75,000 items

British Empire Postage Stamps, beyond 5,000 items

Rest of Word Postage Stamps, beyond 20,000 items

World’s Government Postcards and Envelopes, beyond 8,000 items

Deed Stamps (Fiscal), 1d. to £3,000, since Act, 1964, beyond 2,000 items

Engravings and various Postal items, some thousands

Book-cases, etc. etc.

Duplicate Books and Papers, many tens of thousands (for beneficial use of the collection)13

The Oxford Rejection

As early as 1892, Bellamy was of "a growing desire” that the result of his “labour & time spent in collecting should not be lost or scattered” either within or after his lifetime and that his “collection should be kept intact & well looked after: a thing which may not be attended to, if left in ‘private’ hands.”14 The bequest of the Earl of Crawford’s library to the British Museum would have only strengthened his resolve to donate his literature and stamp collection to a public institution.

In 1916, he informally broached the topic with the one obvious institution that he had always had in mind: the University of Oxford.15 But he was asked to wait for the end of the Great War. In 1920 he made a formal offer, first through its chancellor, the Marquess Curzon, then to two vice chancellors, and then to the registrar. He had a few conditions though. The collections needed to be kept intact and “allowed to be exhibited, inspected and rendered of use under suitable safeguards (especially against strong light).” For the library, he wanted each separate leaflet, paper, number, or book be stamped, and a book plate inserted indicating that the item was part of the “Bellamy Philatelic Library.” Further, most of his books were in their original state and he desired that the collection be so preserved and even if any portion needed to be bound, he didn’t want any of the edges of the papers to be trimmed or any wrappers or advertisements to be omitted. Finally, as regards the college stamps, he wanted the collection to be called the “Bellamy Philatelic

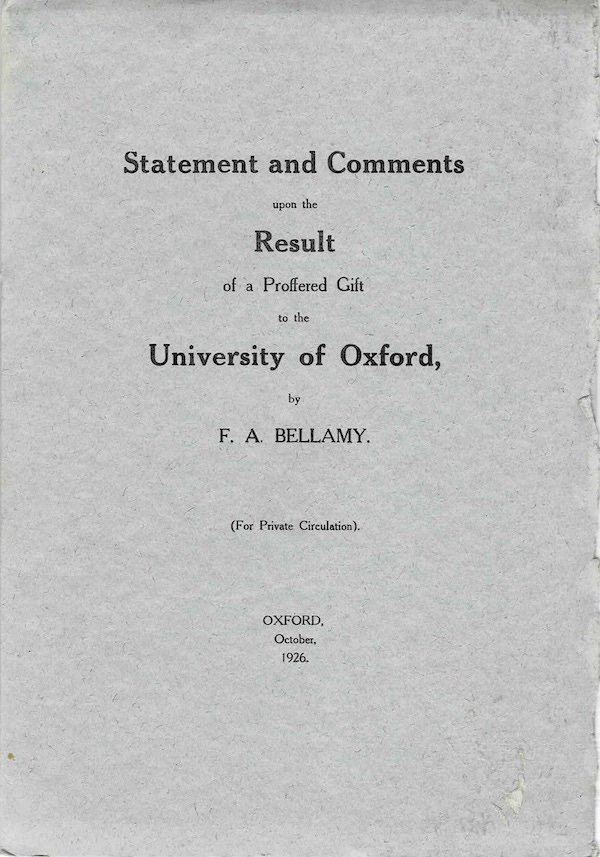

The offer was rejected six years later in April 1926. The University’s Hebdomadal Council made the decision "on the ground mainly that philately is not a branch of the University studies and that the collection, however desirable, would be a source of expense to the University which it would not be justified in incurring."

Bitterly hurt and affronted, Bellamy wrote two letters, one which was printed in The Times of June 9, 1926, and the other more detailed one in The Oxford Times of June 25, 1926. In them, Bellamy expressed his annoyance that his offer, which should have been discussed in the university’s convocation, was rejected by the majority of the council, and not referred to the former. He claimed that he had offered to bear all present and future expenses arising from this gift. Only space was required, of which there was enough in several university buildings. Further, if it ran short afterwards, the items could be removed or destroyed then! He felt that the university’s council had failed to appreciate the importance of postal history. Unsaid was that if the British Museum could accept the Earl of Crawford’s bequest, why couldn’t the University of Oxford receive his gift, which was of an equally high standard.16

In October 1926, these two letters were reprinted as a monograph titled Statement and Comments upon the Result of a Proffered Gift to the University of Oxford (Figure 5). This small booklet of 12 pages is quite scarce now.

Sale of the Bellamy Collection

Within a few days of the Oxford rejection, on April 19, 1926, Bellamy made a codicil to his last will that stipulated that his collection should be offered to Cambridge University, Oxford’s great rival!17 And in case Cambridge refused, to St John’s College (Cambridge) and/or Queen’s College (Cambridge).

While Queen’s had provisionally accepted, it was reportedly persuaded to decline it in view of the financial position of his two nieces, Ethel and Edith. After his death, Bellamy’s estate was found to be worth a gross £1,577 10s 5d and net £1,234 17s 11d; the bulk of its value must have been embedded in the philatelic collections. If they had been gifted away, the nieces would have struggled to make do; apart from the “residue” of the estate, Ethel was given duplicate stamps and Edith all articles of jewelry and silver and fifty pounds!

Bellamy’s codicil also provided that if none of the public institutions showed interest in his bequest, his executors and trustees (one of who was Ethel) should first offer his library to the RPSL. However, the Royal declined as a “very great percentage of the material was already represented” on their shelves, and they didn’t want to purchase the library as a whole.

Queen’s and RPSL’s decline meant that the executors were free to dispose the whole collection by auction or private sale and the money so raised could go for the benefit of the nieces. The college stamps were acquired by philatelist and dealer Charles Nissen and some other items by John Johnson.

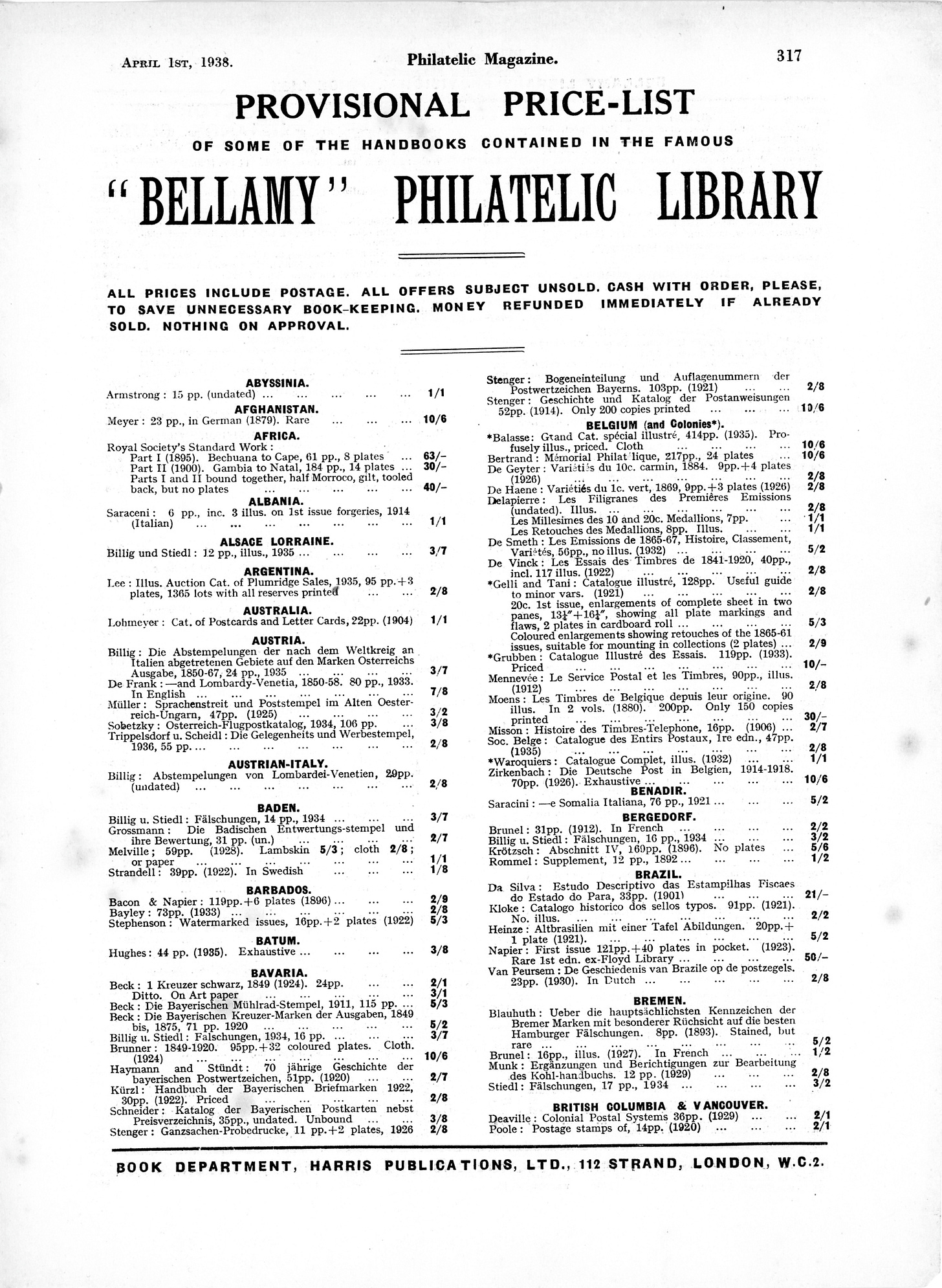

Bellamy's library, which had cost him about £3,000, was sold to philatelic literature dealer and publisher, Albert Henry Harris (1885-1945) in 1938. It is said to have weighed around 10 tons. Harris, who was the publisher of Philatelic Magazine, soon started bringing out price lists of titles from “the largest philatelic library in the world”. The first such was published in the magazine’s issue dated April 1, 1938 (Figure 6). Similar lists continued to be seen into the 1940s.

Since then, working their way through numerous literature dealers and auctioneers, including Francis Hugh Vallancey (1879-1950), Henry Garratt-Adams (1916-1992), and Harry Hayes (1925-2011), Bellamy's books, as evidenced by his simple bookplate (a rubber stamp 19 mm in diameter in black) on the front covers or inside (Figure 7), have been disbursed far and wide.

Catalog of Bellamy’s Library

For some time, I have known that some of Bellamy’s stamps and ephemera was bought by John Johnson (Figure 8), who had later donated his collection to the University of Oxford’s Bodleian library.

In early 2020, I was closely reading a PDF of the catalog of exhibition of the “John Johnson Collection of Printed Ephemera” that took place in 1971. In one of its pages, it said:

Bellamy was a well–known local collector, who in 1916 made to the University the offer, as a gift, of the whole of his extensive library and collection relating to the world's postal history. At that time it was estimated that the collection contained over 200,000 separate items, and the manuscript catalogue of the library, which is preserved in the Johnson Collection, shows something of the enormous range of the collection.

While I was excited that the catalog of Bellamy’s library still existed, I delayed writing to the Bodleian until July. While the library was shut due to Covid-19 related lock-down, the librarian, Julie-Anne Lambert, was kind enough to email some photos of the catalog as soon as she was back the following month. Further, for my research purposes, she helped me, via the Weston Library Reader Services, get a digitized copy of the catalog.

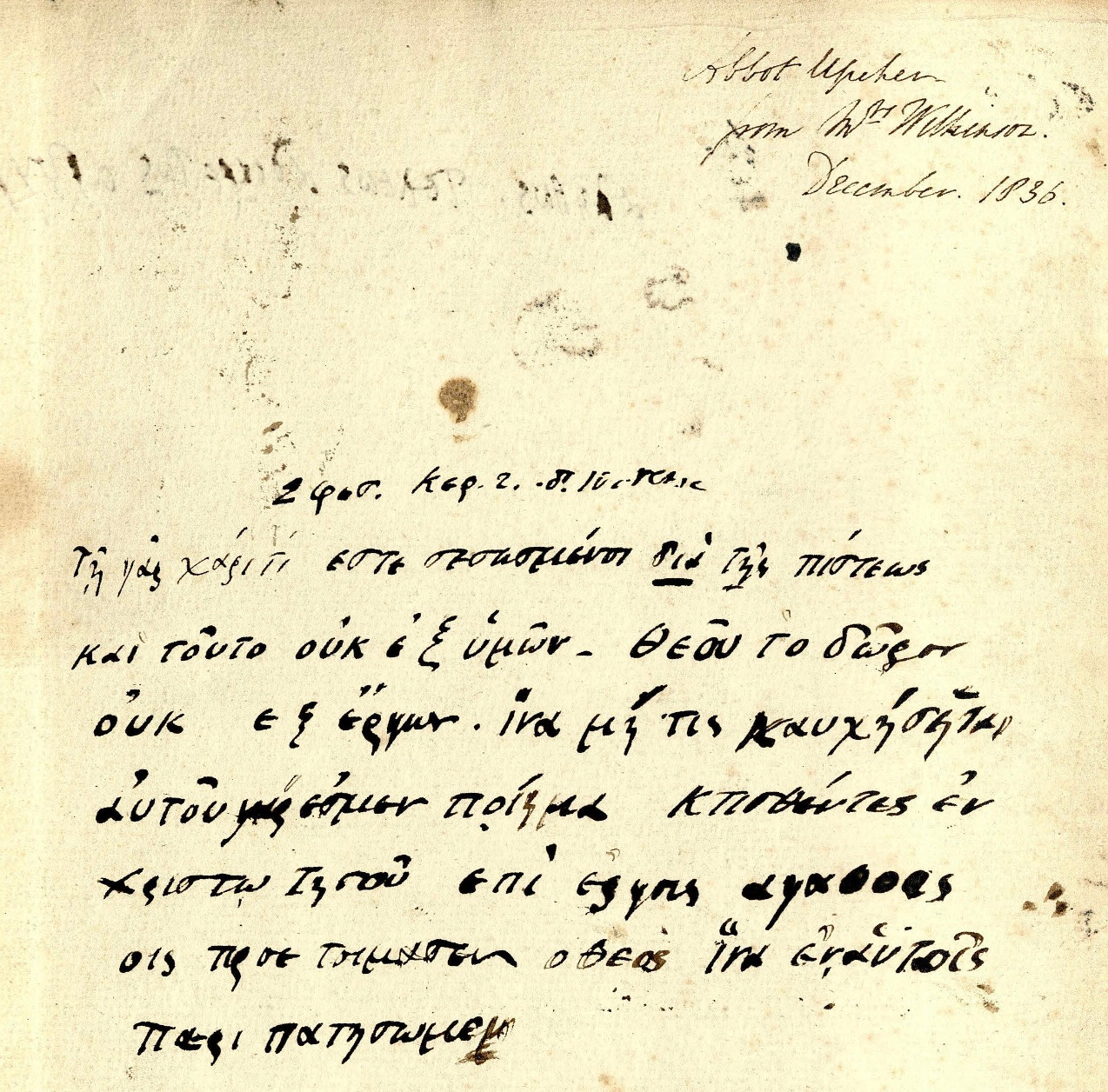

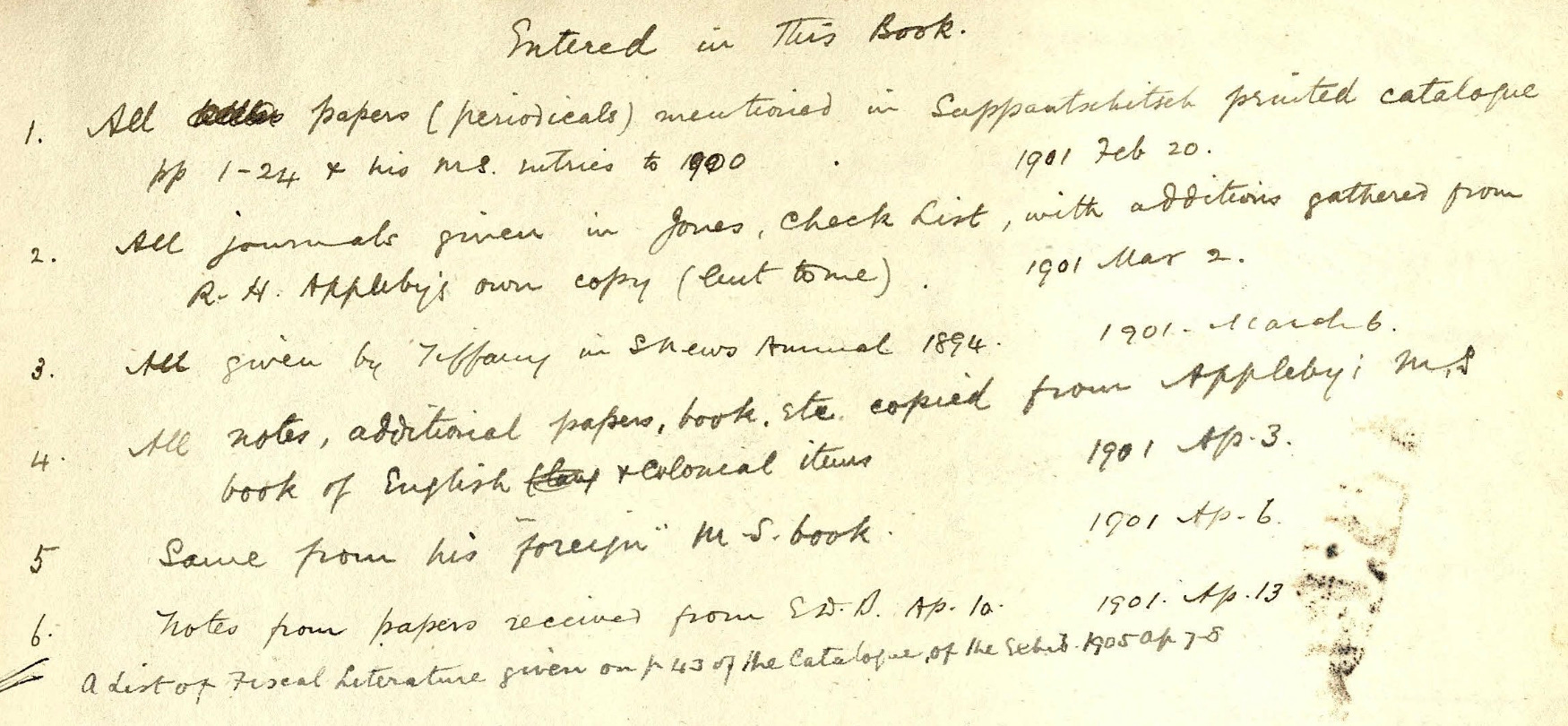

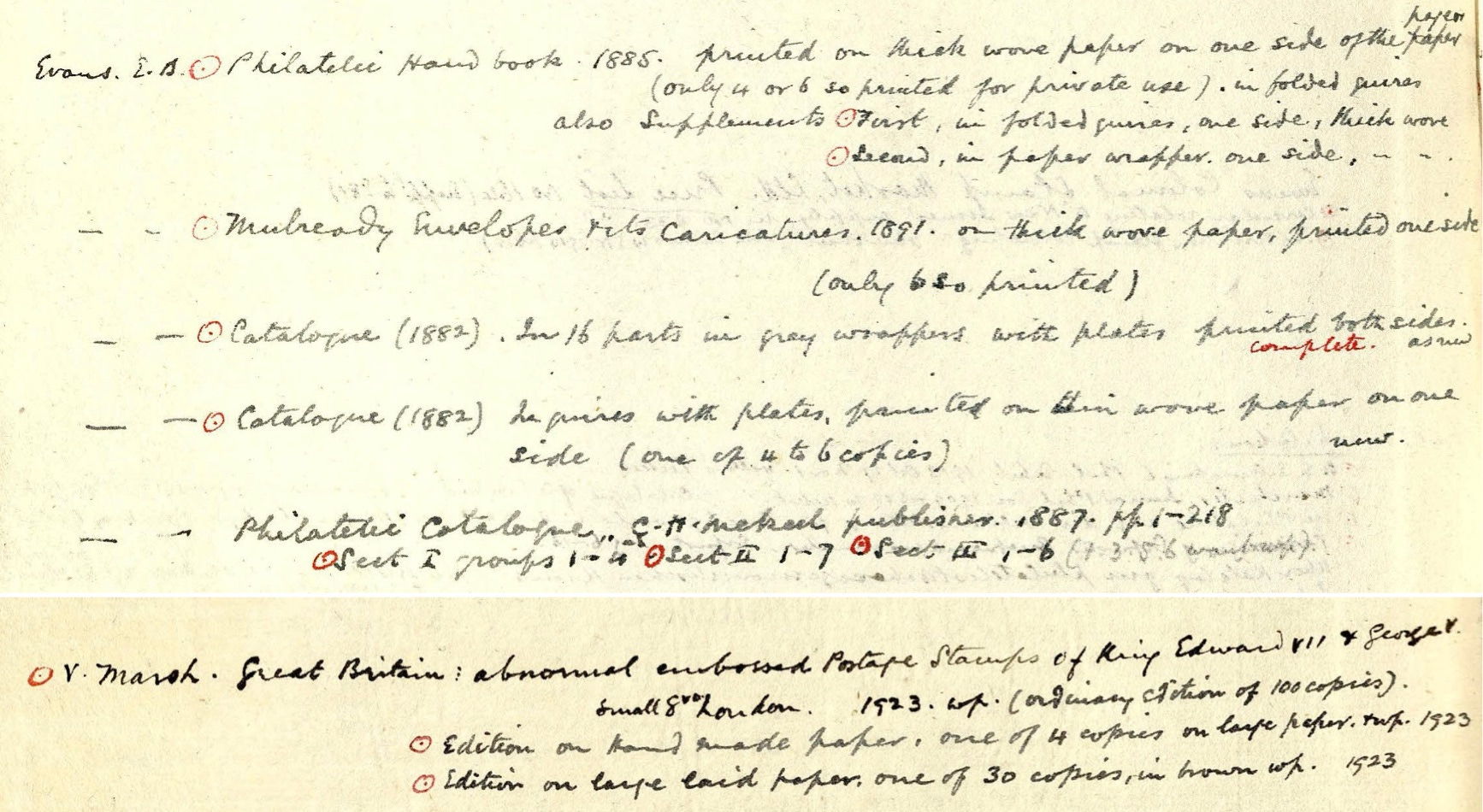

Figure 9 shows writing on the paste-down, very likely in Bellamy’s hand. It indicates that he had started compiling the catalog sometime in 1892. We have noted this year before; it was when Bellamy started on his literature quest.

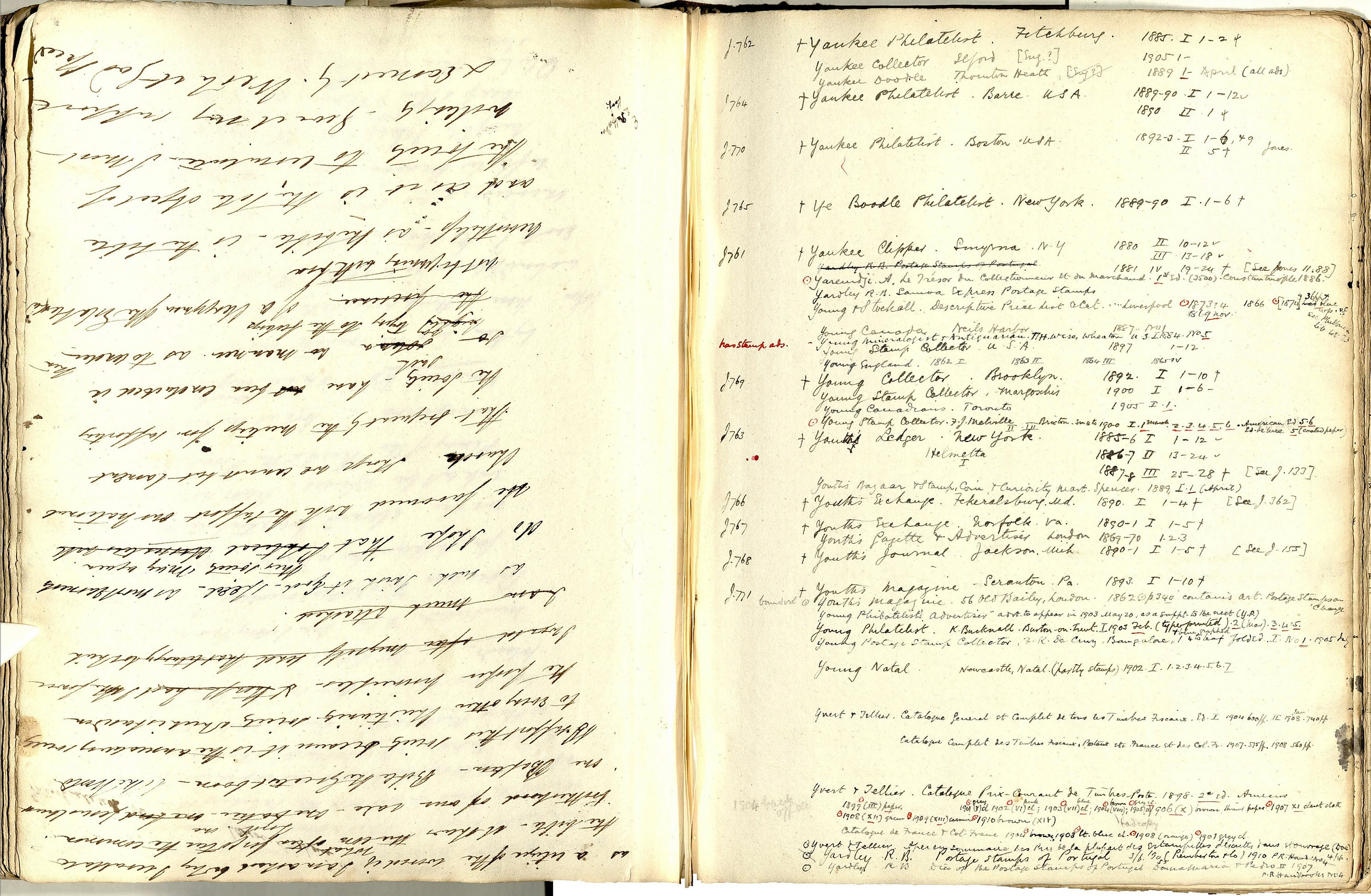

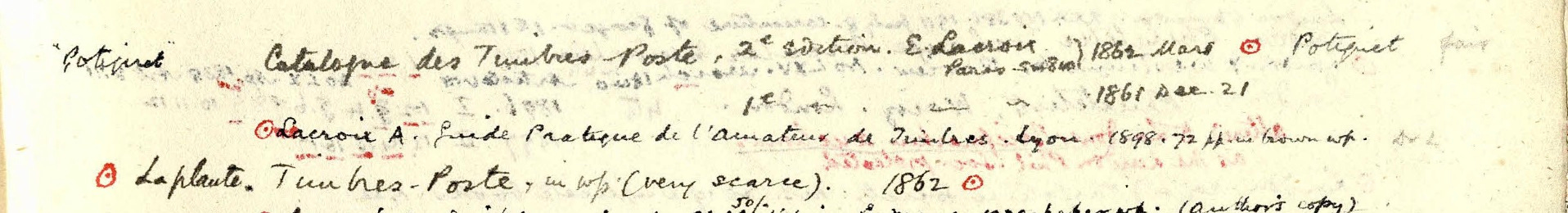

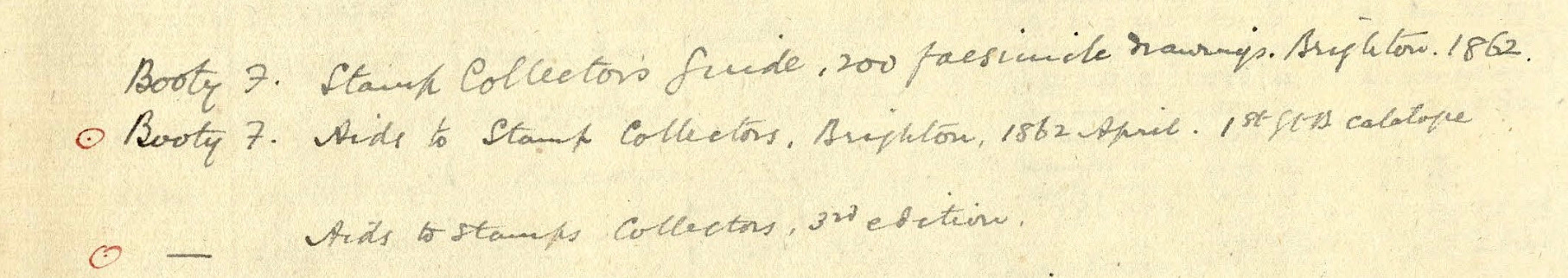

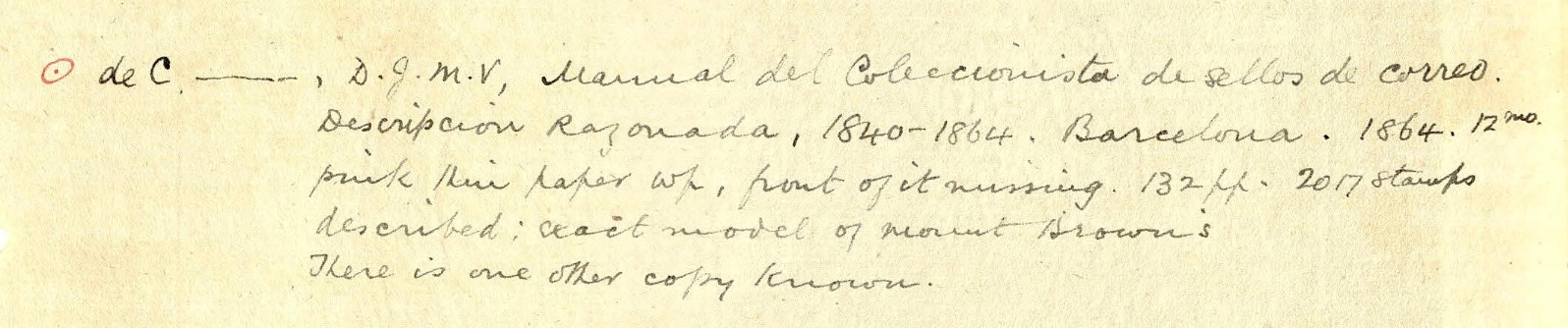

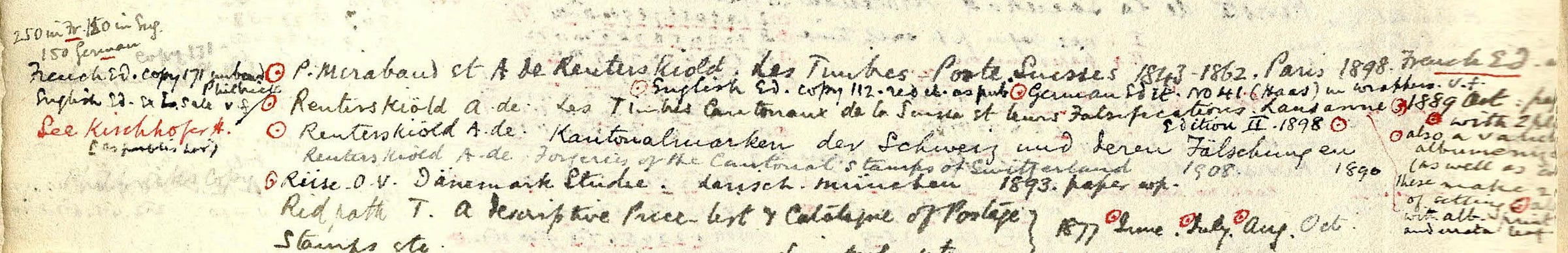

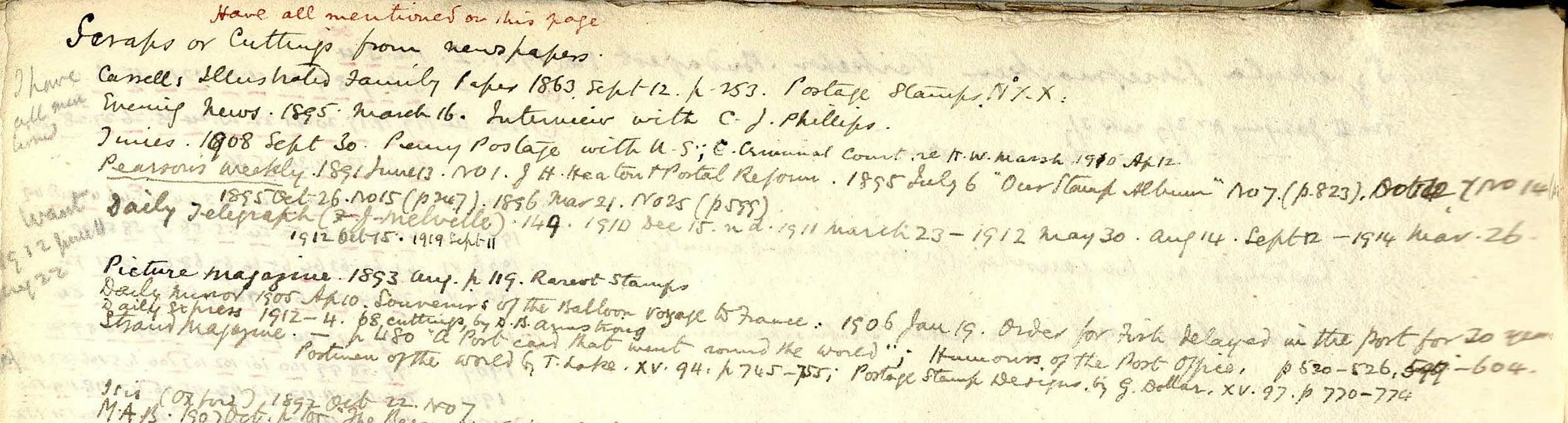

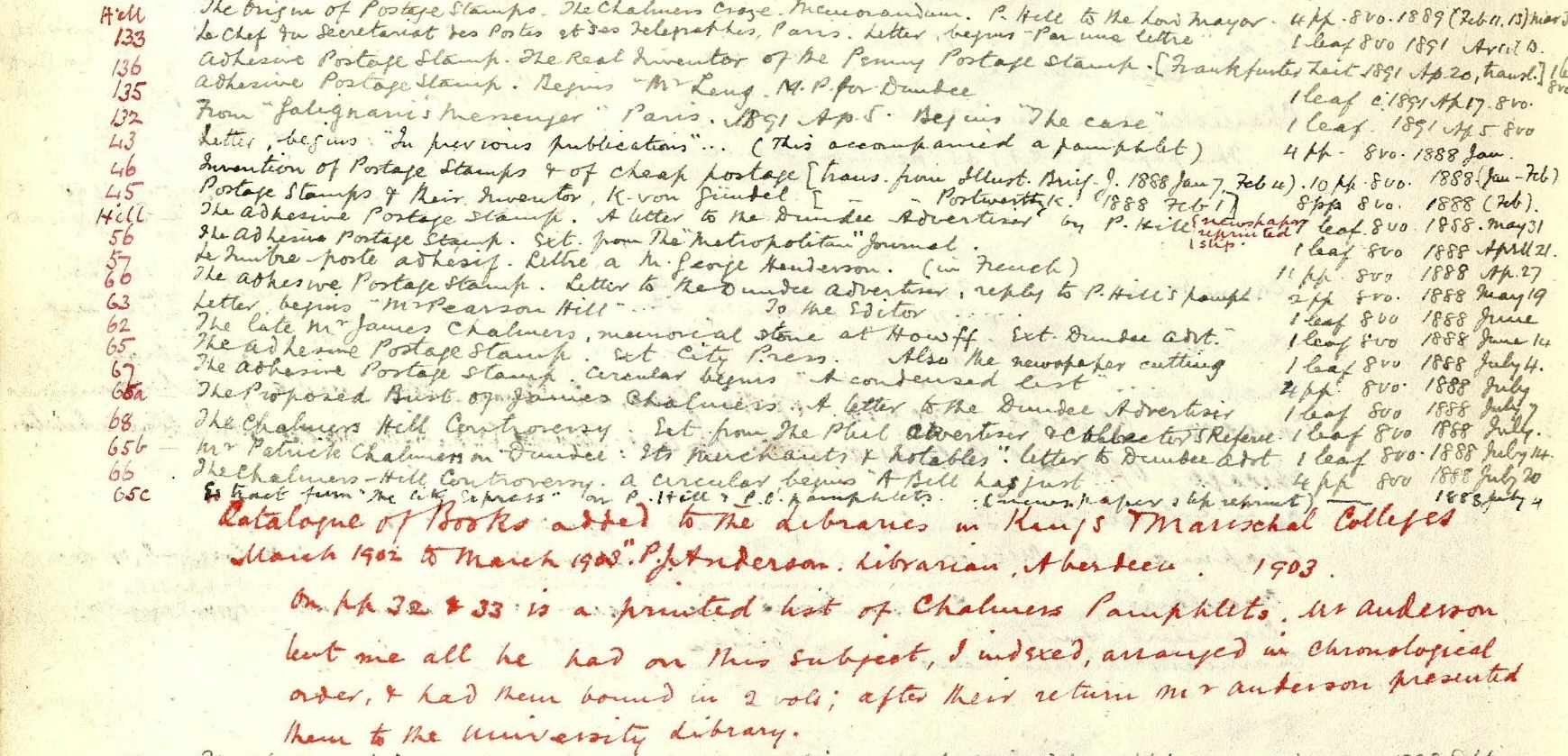

To start the catalog, Bellamy got hold of a large sized notebook of empty pages which had belonged to prior owner(s) (Figure 10). It wasn’t actually entirely empty since a few pages (in the front and at random places inside) were written-in in one or more different handwriting! (Figure 11). No matter: Bellamy flipped the book over and started his magnum opus from the rear!

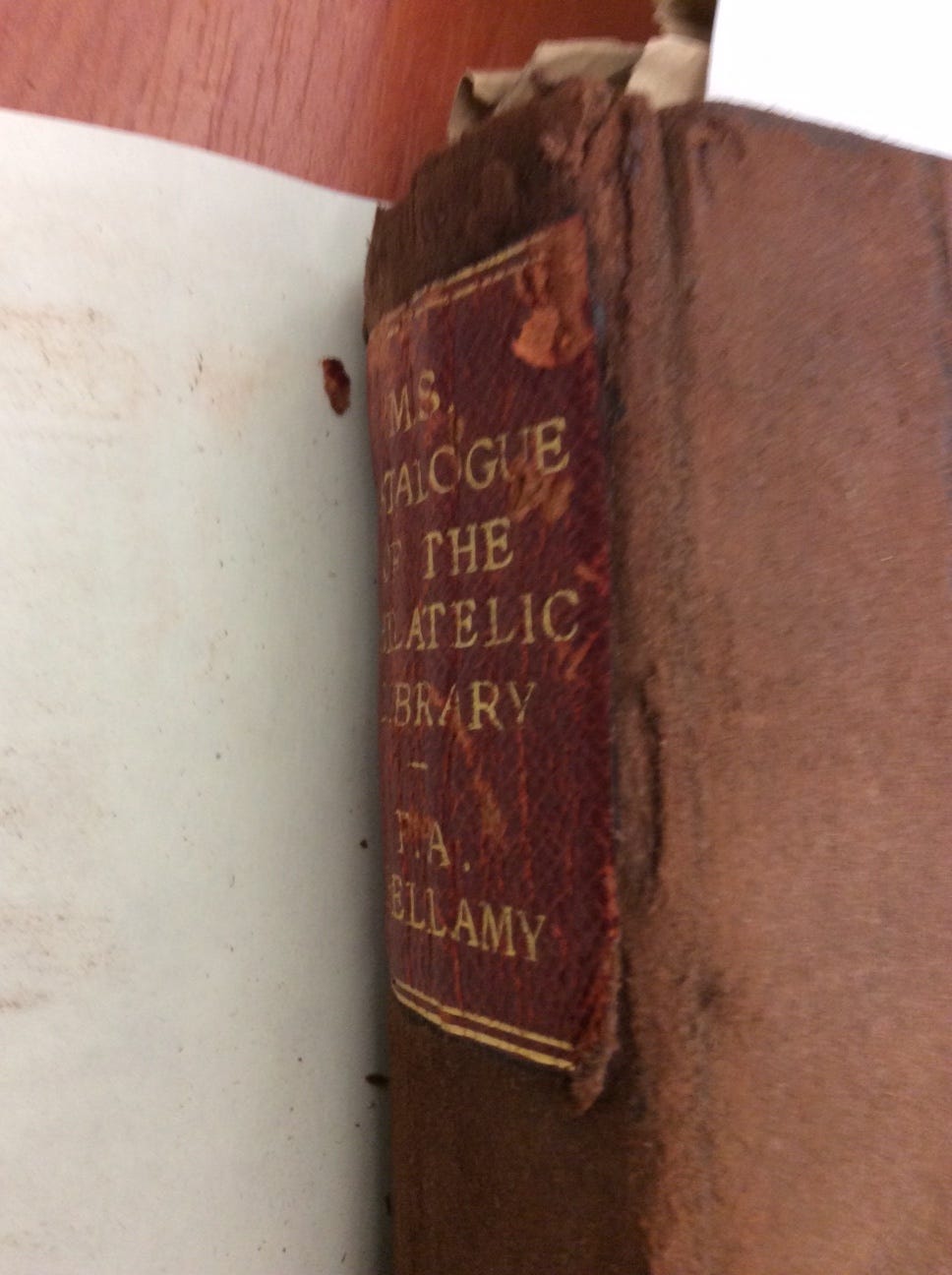

Sometime later, Bellamy got the original book rebound; it’s also possible that he just got gold lettering embossed on the original’s spine (Figure 12).

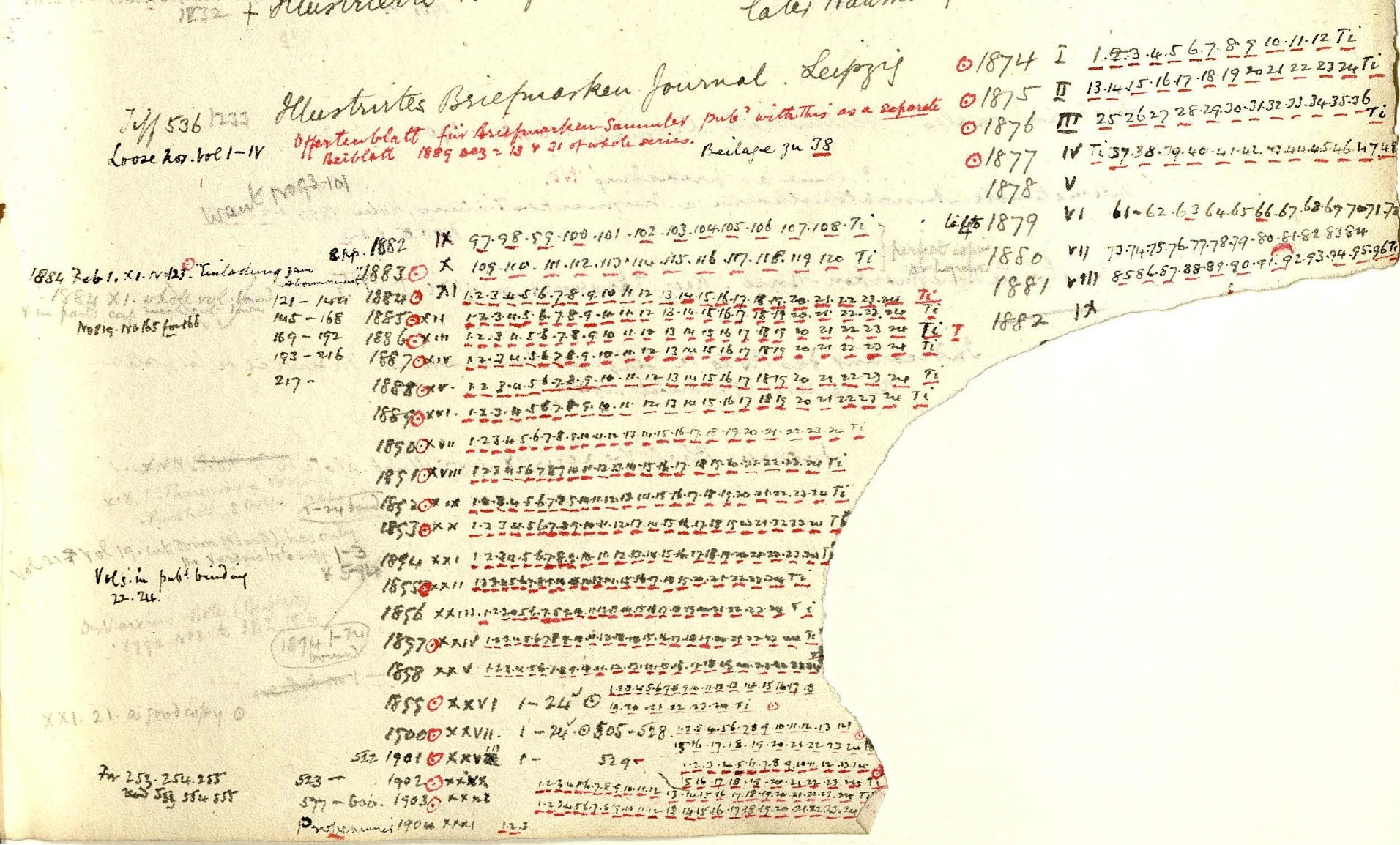

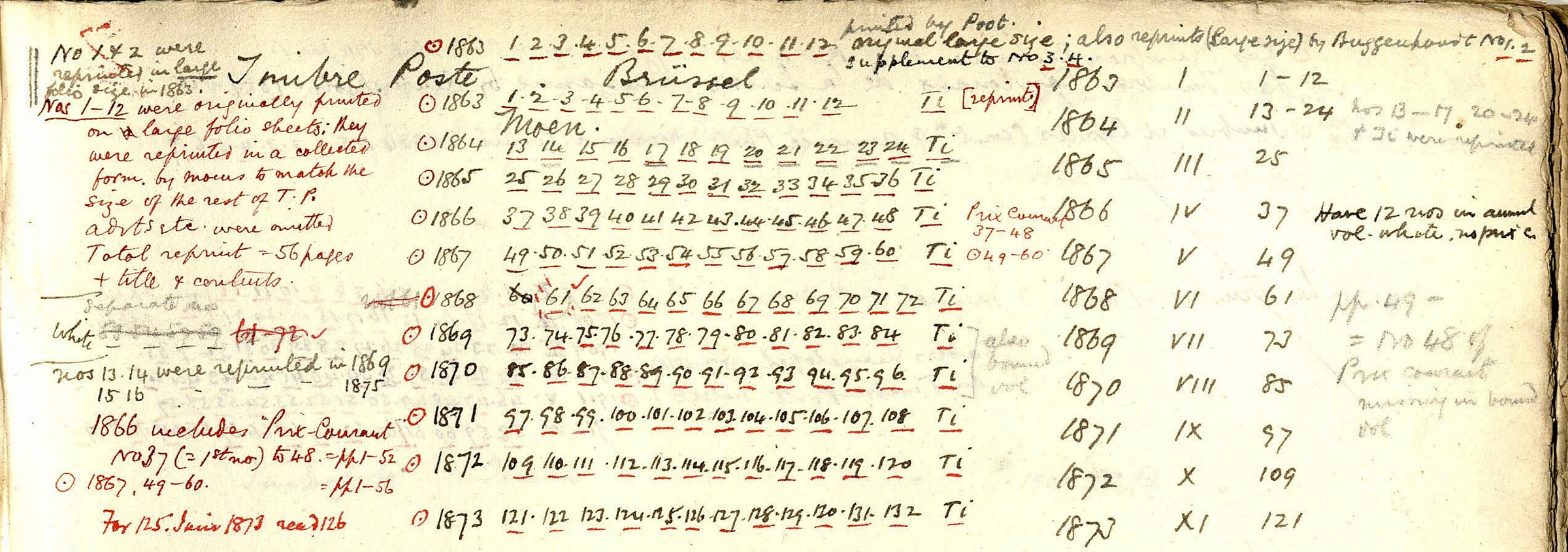

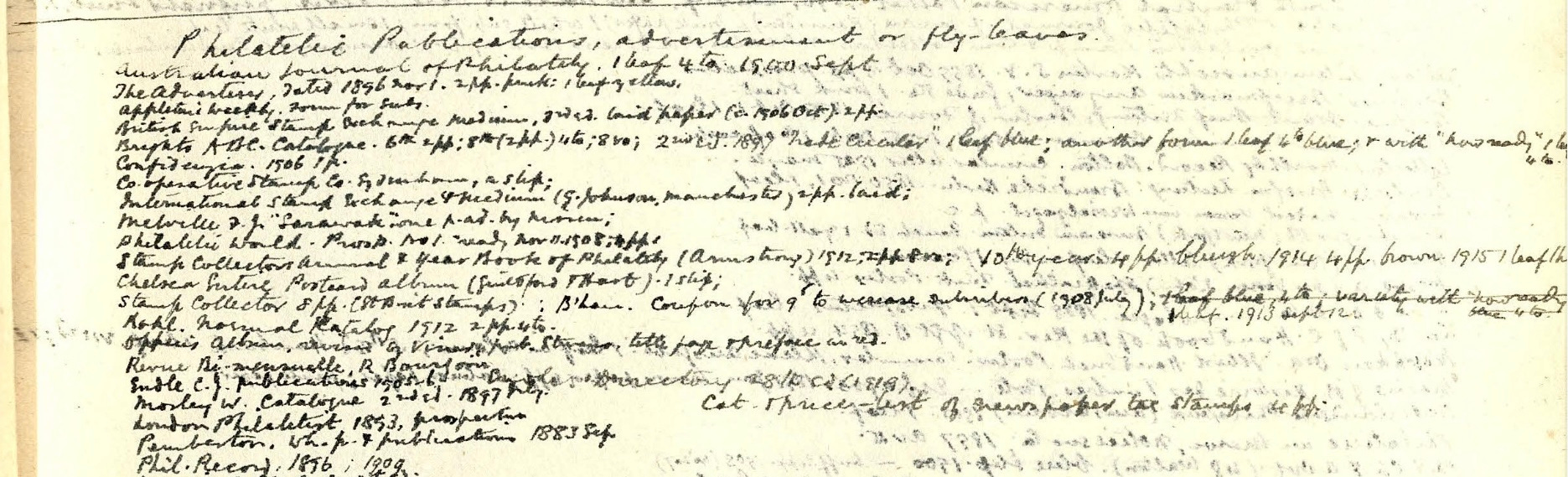

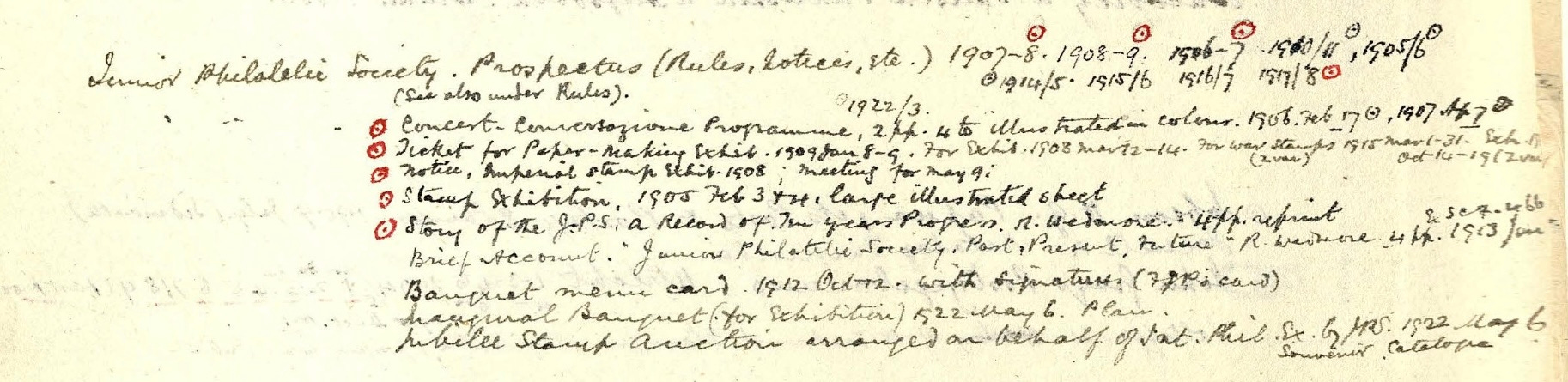

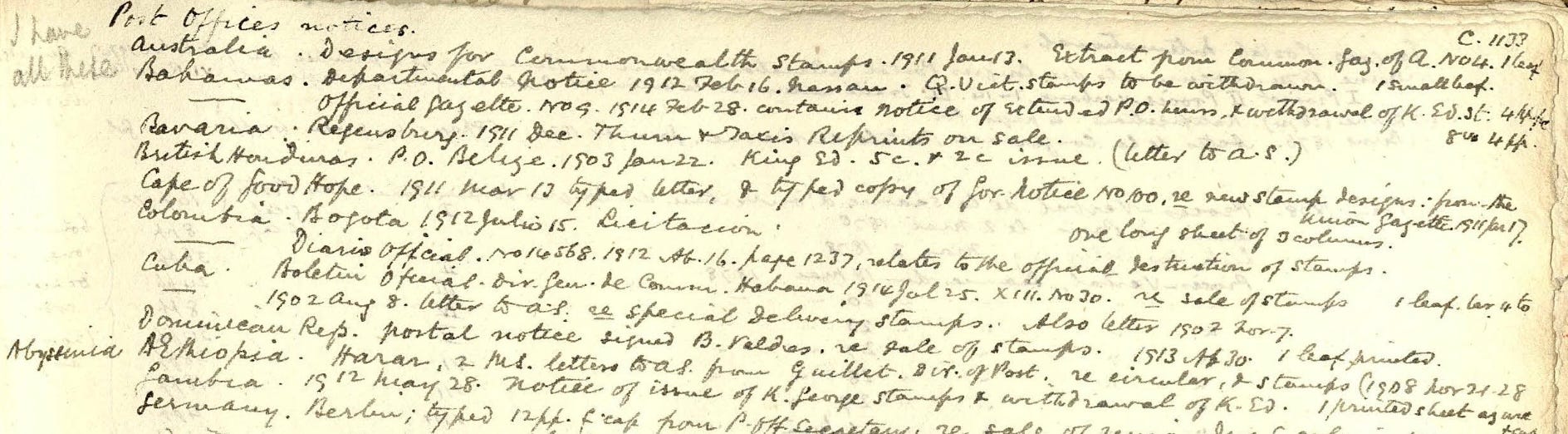

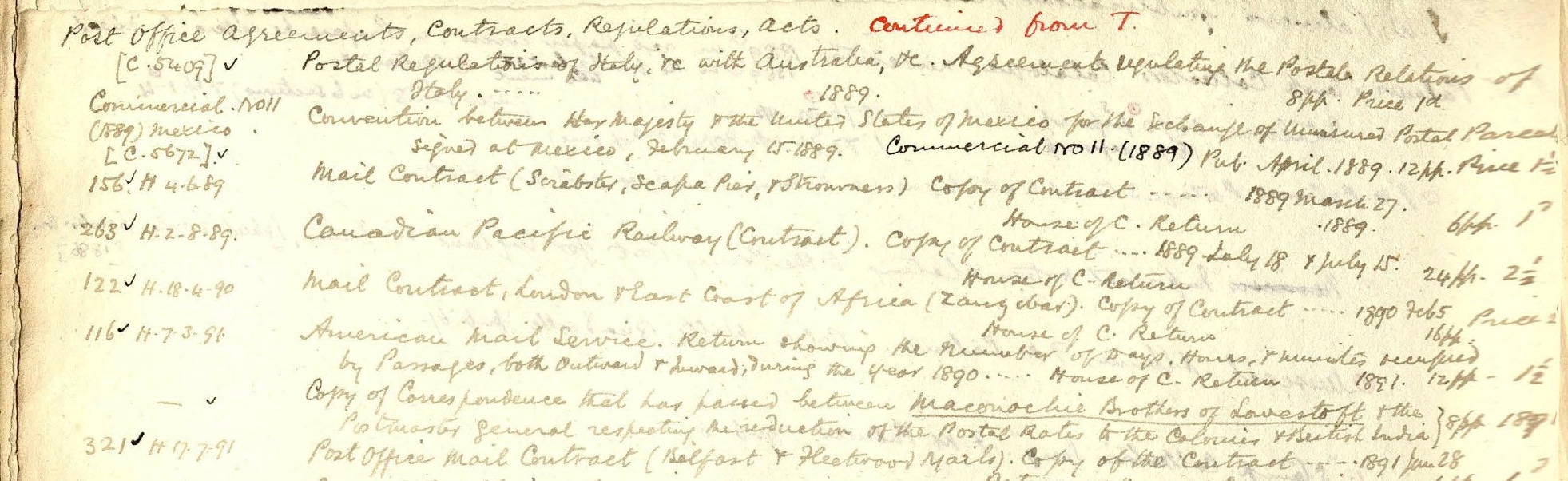

The pages of the book are probably handmade paper with deckle edges. The digitized copy shows 468 sides of paper in it. When Bellamy started writing, he used only one of the two facing sides (often the right) of paper; the other was reserved for further entries at some later date. Hence, while most of the pages in the book have been made use of and some excessively so (Figure 13), there are several, mainly those on the “other” side, which are only partially written in. Very few pages are totally empty.

Bellamy uses black ink throughout. He sometimes resorts to red ink when he wants to make important notations; and pencil to usually record missing issues or note the state of existing ones (Figure 13).

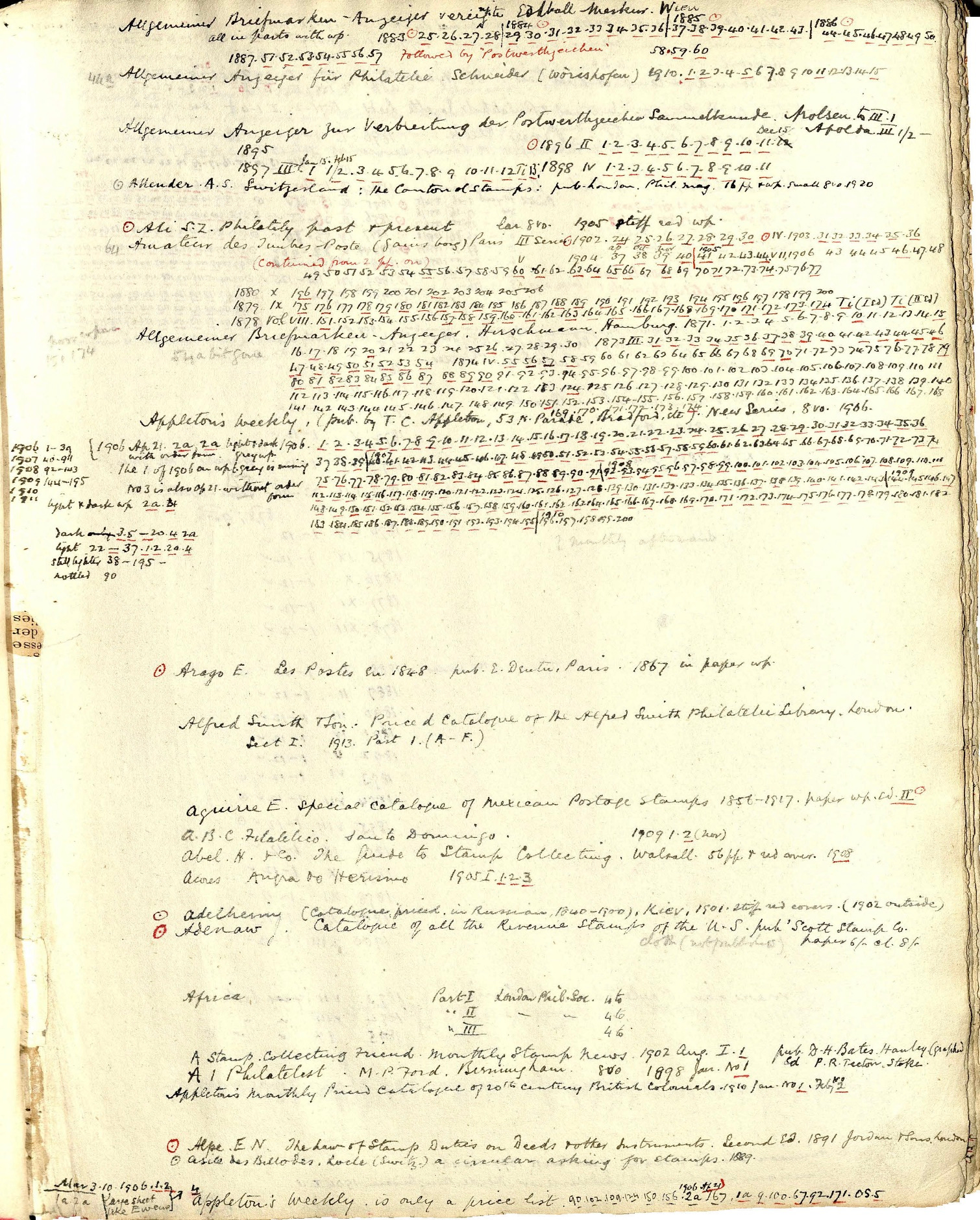

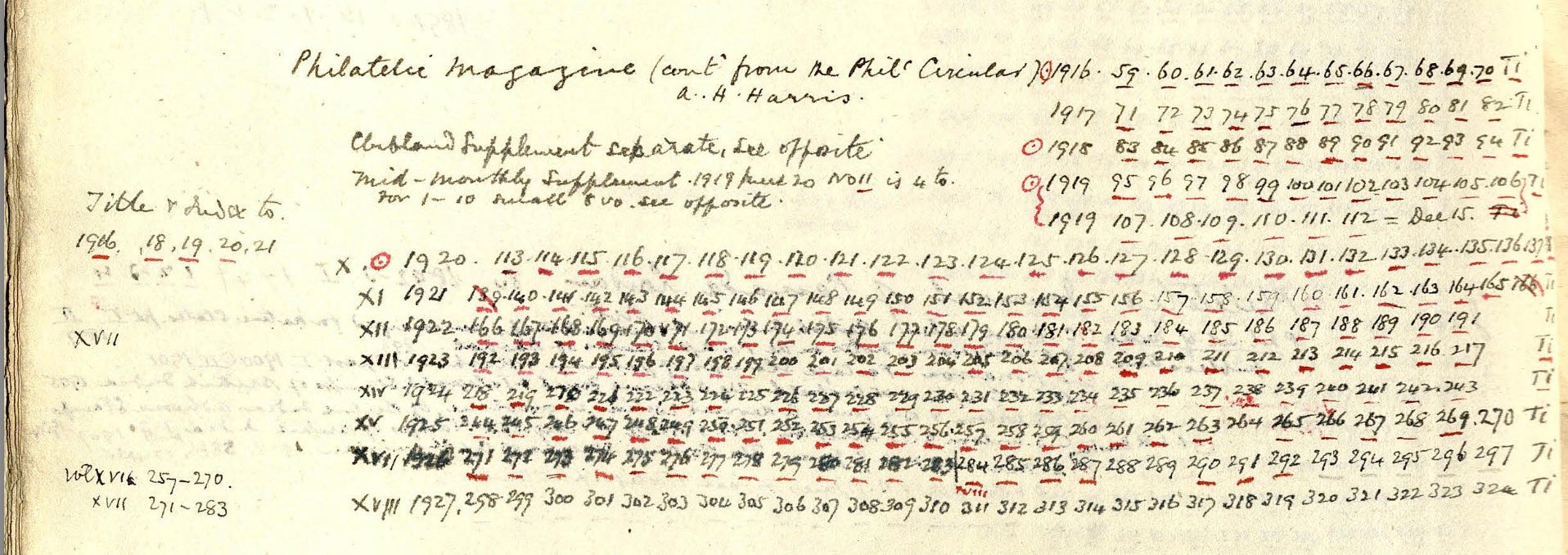

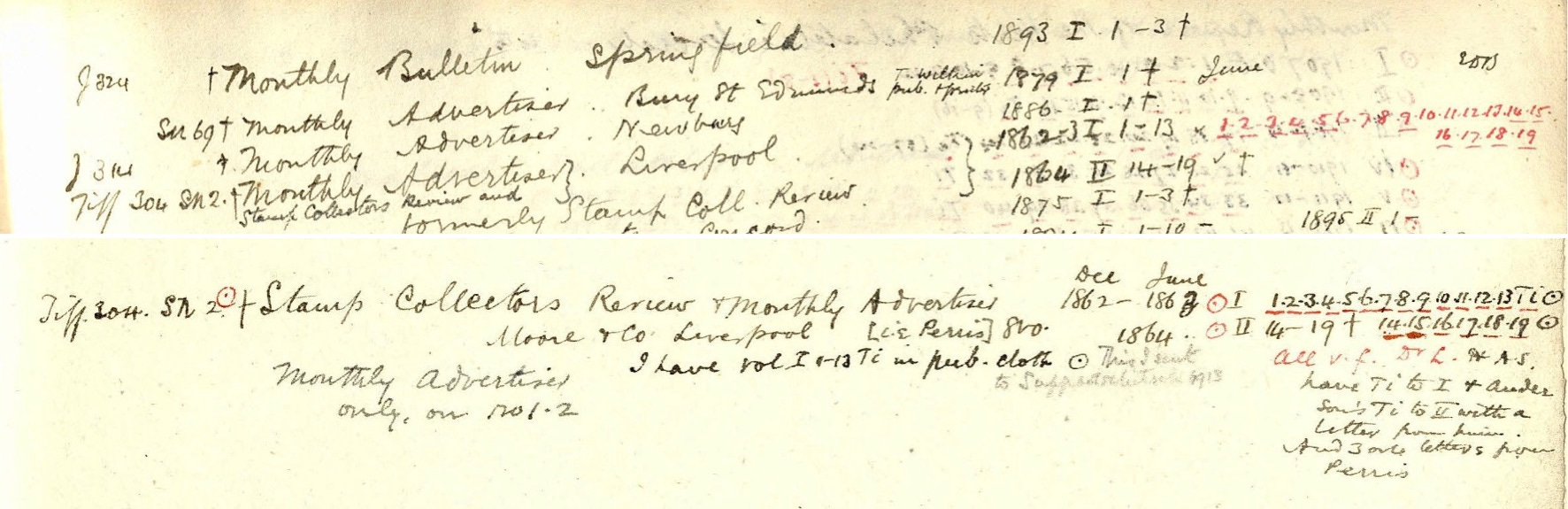

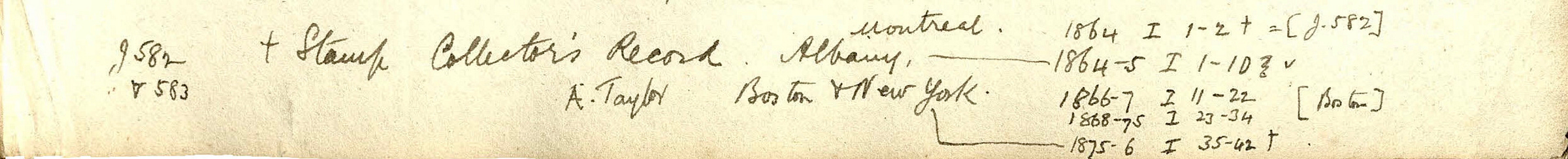

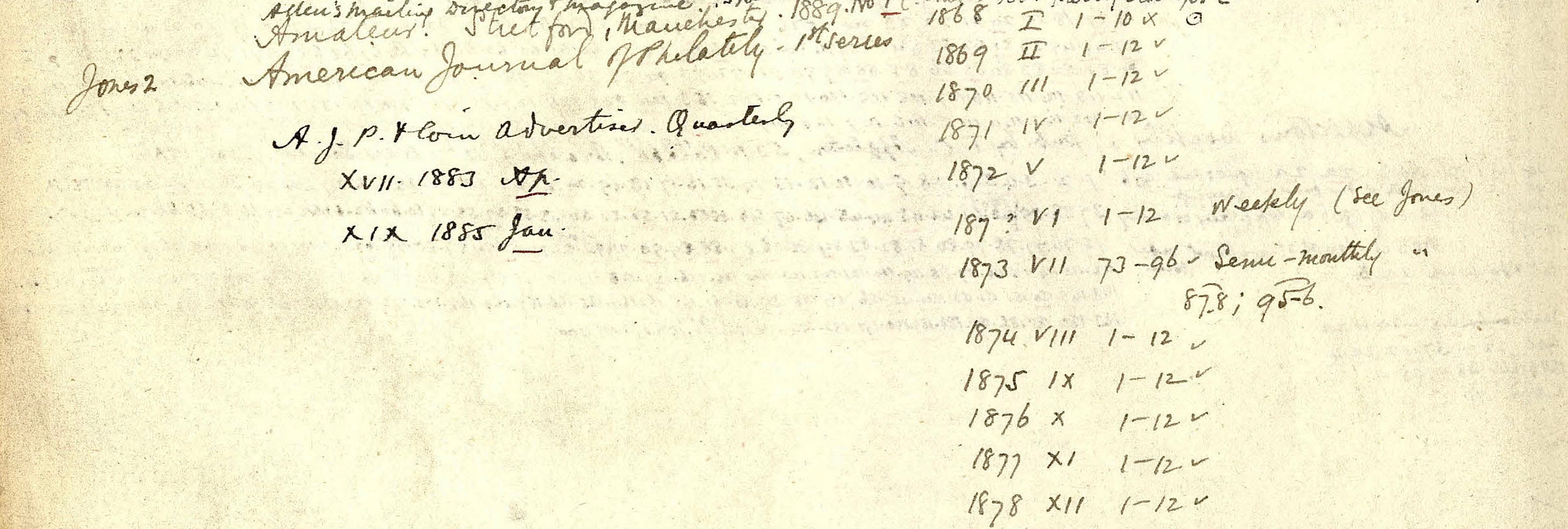

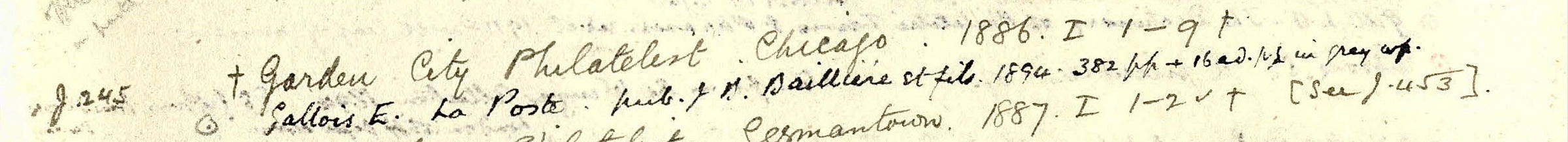

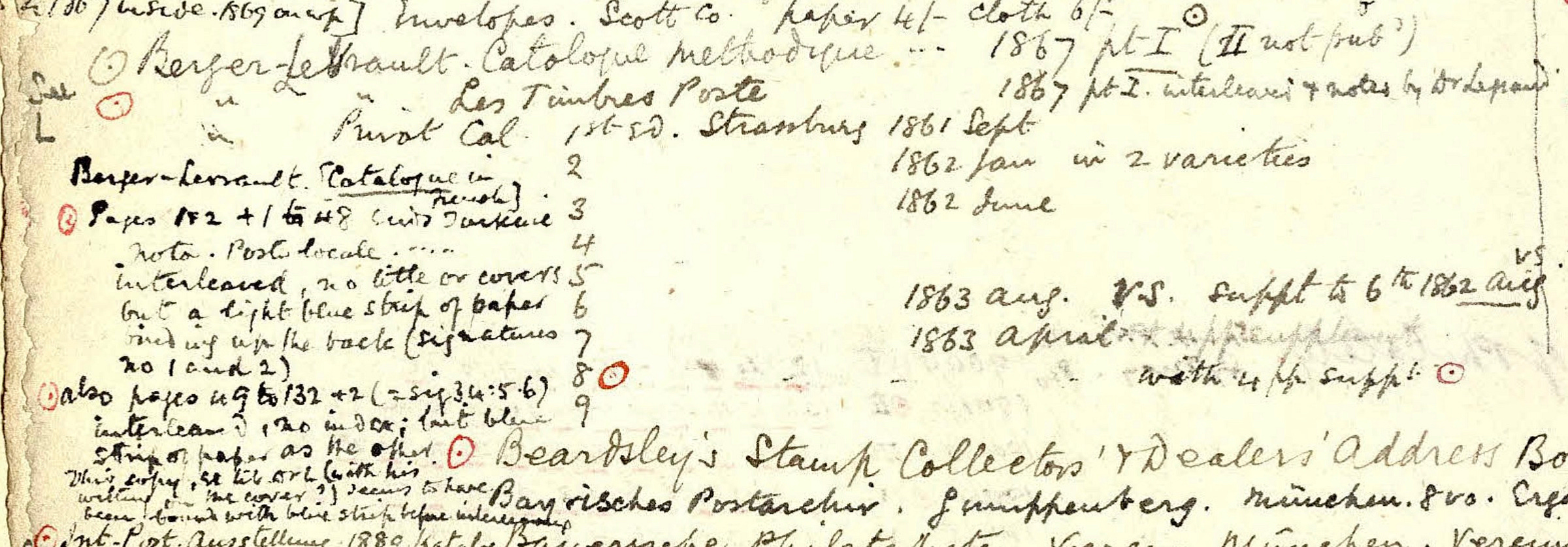

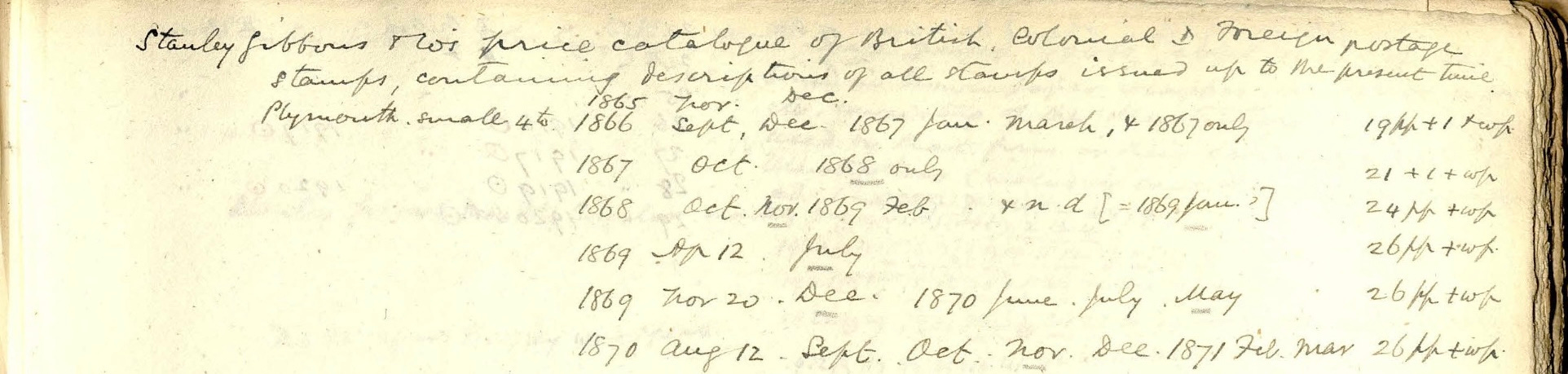

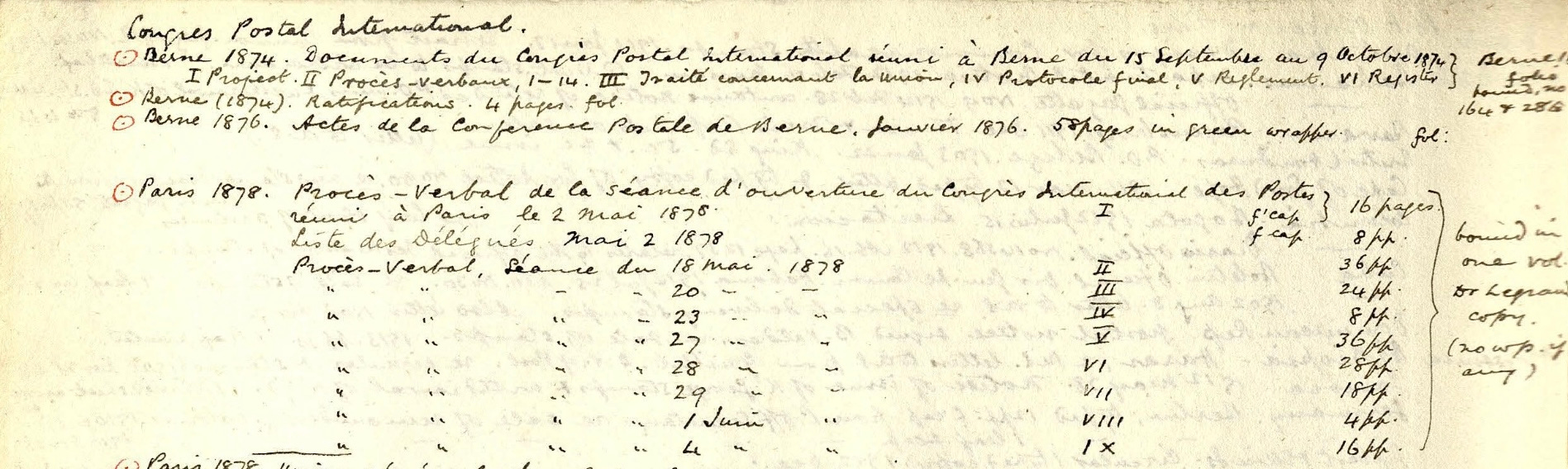

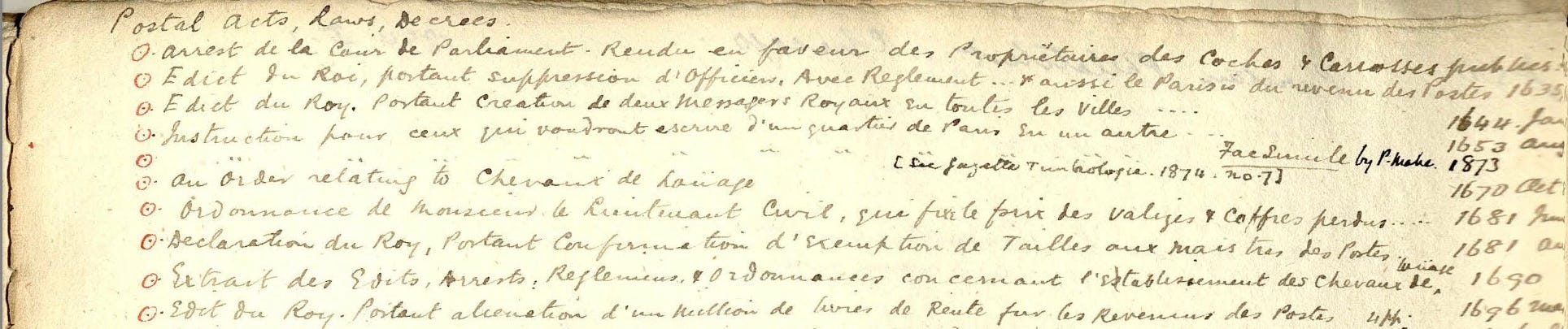

Journals are recorded alphabetically by title; articles such as “the” or “der” or “die” (German) or “la” (French) are ignored. Typically, the name of the journal is followed by the place of publication, and then by the year and volume; against the latter, the number of issues is noted.

Handbooks are recorded usually by the author’s name, or in its absence, by the publisher. It’s followed by the title and other details such as the place and year of publication, the edition number, and the number and size of pages. Some cross-referencing is given; for example, in Figure 14, toward the bottom, one can see the entry “Africa,” which refers to Parts I to III of a publication of the “London Phil. Soc.” (today’s Royal Philatelic Society London). More details are under entries beginning with “L.”

However, no attempt is made to segregate titles per their categorization. For example, journals vis-à-vis handbooks (Figure 14). In contrast, the Crawford Catalogue groups publications holdings into “Part I. Separate Works” and “Part II. Periodicals” to facilitate searches. But to be fair, the Crawford is a finished work whereas Bellamy’s catalog was for personal use and a work-in-progress.

Further, just as the Crawford Catalogue is a bibliography of all books pertaining to philately, and not just a listing of those in the Earl’s library, Bellamy’s catalog is similar. It notes works present in his library as well as those missing from it.

There are a few symbols in the book that I can’t decipher at the moment. For example, what does the red dot within a circle denote? What does an underline under a journal’s issue number mean (see Figures 13 and 14)? Do they always mean that Bellamy possessed a copy of that work?A list of references noted in the front seems to indicate that Bellamy updated the catalog sometime into the early 1900s only (Figure 15). So, did Bellamy stop collecting and/or updating his catalog sometime then? Secondly, he doesn’t mention the Crawford Catalogue as a source of reference. Why?

A perusal of the catalog gives the impression that Bellamy had eased down on collecting by the early 1910s. In 1920, the year he made his offer to Oxford, he also warehoused his library in “boxes and parcels”. A perusal of the catalog shows entries for some contemporary journals as late as 1927 (Figure 16) but not much else.

As for the second question, Bellamy did own an interleaved copy of the Crawford.18 In it, one can see annotations in Bellamy’s hand, as also clippings pasted in. So even though it isn’t mentioned in Figure 15, it’s likely he used the Crawford, to a limited extent, to build upon his own work.

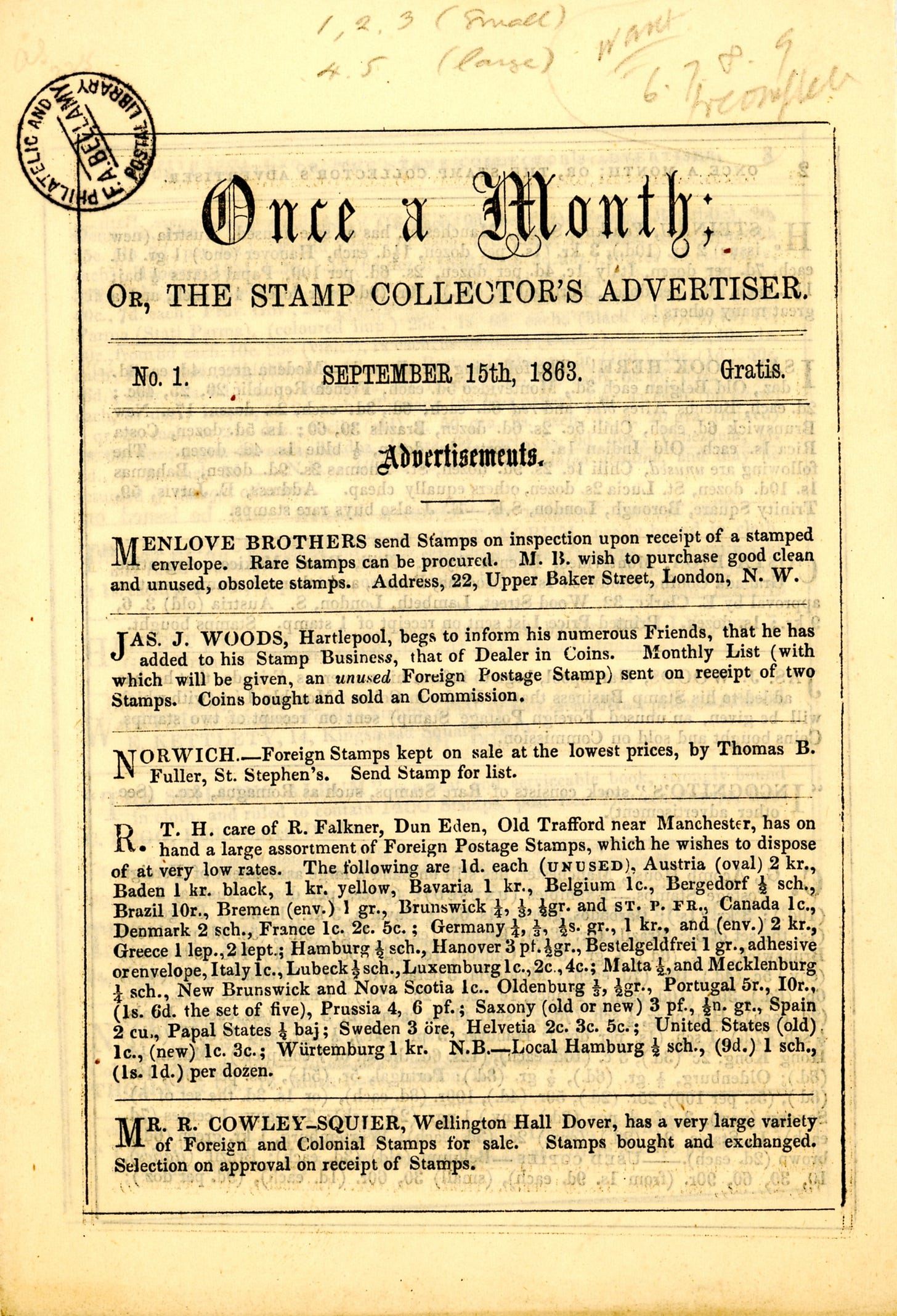

Given that Bellamy’s library rivaled that of the Earl of Crawford, it’s to be expected that it was very strong in 19th and early 20th century literature. It obviously contained most of the early journals (Figures 17 to 21), stamp catalogs (Figures 22 to 25), and handbooks (Figures 26 to 27).

A picture is worth a thousand words and hence, many illustrations of entries from the catalog follow.

Bellamy’s library also contained other philatelic items of a more ephemeral nature such as auction catalogs (Figure 28), dealer price lists (Figure 29); prospectuses and advertisements (Figure 30); philatelic society reports, rules, and statutes (Figure 31); newspaper cuttings (Figure 32); and even stamp albums. One subject that caught my attention were the various books, pamphlets, and letters concerning the Chalmers-Hill controversy (Figure 33).19

Bellamy also collected publications related to the post office such as postal acts, laws, and decrees (Figure 34); post office notices (Figure 35); postal contracts, conventions, agreements, and reports (Figure 36); and postal congresses reports (Figure 37).

Conclusion

This article has sought to provide an overview of Frank Bellamy and the catalog of his library. With respect to the latter, I am aware that I have only scratched the surface. The more one pages through the catalog, the more it reveals. No doubt, bibliophiles and researchers will discover several interesting aspects by studying it in detail.

What next? One obvious way forward would be to work with the archival team of the John Johnson Collection and transcribe Bellamy’s catalog. This will surely make it more useful to philatelic historians and bibliographers. It would, however, be a huge undertaking requiring immense determination and/or resources. Given philately’s pecking order in the real world, and that of philatelic literature within philately, the transcribed work is unlikely to set the Thames on fire! So, who will bell the cat(alog), if any?

Acknowledgements: Julie-Anne Lambert, librarian of the John Johnson collection, who helped me find the catalog. Jan Vellekoop for going through the draft and providing valuable feedback.

References

Adam, M.G. 1996. “The Changing Face of Astronomy in Oxford (1920-1960).” Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society 37 (June): 153-179.

Bacon, E.D. 1908. “The Philatelic Library of the Earl of Crawford, K.T.” The Journal of the Philatelic Literature Society 1 no. 2 (April): 25-30.

Bellamy, Frank Arthur. 1896. “A Subject Index of Stamps.” The London Philatelist 11 no. 59 (November): 303-305.

Bellamy, F.A. 1926. Statement and Comments upon the Result of a Proffered Gift to the University of Oxford by F. A. Bellamy. Oxford: The Author.

Birch, Brian J. 2018. Philatelic and Postal Bookplates. Montignac Toupinerie, France: The Author.

———. 2018. The Philatelic Bibliophile's Companion. Montignac Toupinerie, France: The Author.

———. 2018. Bibliography of Current-Awareness and Retrospective Indexes. Montignac Toupinerie, France: The Author.

Farmer, Bonny. 2001. “The Philatelic Collection of the Free Library of Philadelphia.” The Philatelic Literature Review 50 no. 4 whole no. 193 (4th Quarter): 268-273.

(Hall, Thomas William). 1936. “Frank Arthur Bellamy” The London Philatelist XLV no. 531 (March): 51-53.

———. 1937. “The Collection of Oxford and Cambridge College Stamps of the Late Mr. F.A. Bellamy, M.A., F.R.P.S.L.” The London Philatelist XLVI no. 542 (February): 42-43.

Hughes, A. M. 2016. Oxford Philatelic Society: A History. Oxford: Oxford Philatelic Society.

(Gilbert-Lodge, L. J.) 1938. “The Royal Philatelic Society, London. Annual Report for the Session 1937-38 by the Hon. Secretary.” The London Philatelist XLVII no. 558 (June): 148-160.

Maassen, Wolfgang, and Vincent Schouberechts. 2013. Milestones of the Philatelic Literature of the 19th Century / Les Jalons de la Littérature Philatélique Au XIXe Siécle. Monaco: le Musée des Timbres et des Monnaies de Monaco.

Negus, James. 1991. Philatelic Literature: Compilation Techniques and Reference Sources. Limassol, Cyprus: James Bendon.

———. 2004. “Researching the Earliest Gibbons Catalogue.” The Philatelic Literature Review 53 no. 2 whole no. 203 (2nd Quarter): 109-126.

(Tilleard, J.A.) 1908. “Philatelic Societies Meetings.” The London Philatelist XVII no. 194 (February): 45-48.

Web Sources

Frank Arthur Bellamy on Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Arthur_Bellamy

Oxfordshire Blue Plaques Scheme. www.oxonblueplaques.org.uk/plaques/bellamy.html.

St. Sepulchre’s Cemetery. http://www.stsepulchres.org.uk/burials/bellamy_frank.html

The John Johnson Collection, Catalogue of an Exhibition. https://www.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/86044/catalogue-of-an-exhibition.pdf

James Ludovic Lindasy (1847-1913) was the 26th Earl of Crawford. His library of philatelic literature, popularly known as the “Crawford Library” was about 95 percent complete for all known literature from the early 1860s to about 1912-13.

Ethel Frances Butwell Bellamy (1881-1960) was a pioneering woman astronomer and seismologist. Apart from assisting her uncle in mapping the stars, her major work was to prepare the International Seismological Summary, collating and measuring the records of earthquakes from seismological stations worldwide. Bellamy produced a world map showing the epicenters of the quakes, heralding the modern approach to earthquake seismology. She was made a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1926. On January 30, 1934, she received the honorary degree of MA from Oxford University.

Bodleian Library or “Bodley” is the main research library of the University of Oxford. It’s one of the oldest libraries in Europe and is the second biggest library in Great Britain after the British Library. The Bodleian Libraries group, comprising of the Bodleian Library along with 25 other libraries across Oxford, together hold more than 13 million printed items.

From 1871 to 1886, certain Oxford and Cambridge colleges issued their own stamps to be sold to members of the college so that they could prepay for an inter-college messenger service. The practice was stopped in 1886 by the post office as it asserted its monopoly on postal collection and delivery.

Incidentally, in the meeting of the OPS held on January 24, 1927, Bellamy was asked if he would consent to become president of the society, but he said he much preferred the secretarial side of the work (The Oxford Chronicle, January 28, 1927).

This was carried in The Oxford Chronicle of May 19, 1922, when it reported on a small exhibition, that took place on May 11 and 12 in Oxford, of about 180 items of philatelic literature from Bellamy’s library. While 1892 may have been the year when the idea of indexing struck Bellamy, he must have started his project only in 1894 as he makes clear in his article in the November 1896 issue of The London Philatelist.

The information in this and the following sections have been taken from Bellamy’s last will dated October 28, 1915 and the codicil to his last will dated April 19, 1926 as well as his letters to The Times of June 9, 1926 and The Oxford Times of June 25, 1926.

John de Monins Johnson (1882-1956) was a respected papyrologist (someone who studies papyrus and ancient writings on papyrus) and later printer to Oxford University. Collecting printed ephemera was Johnson’s hobby and by the time of his death, he had assembled some 1.5 million items, divided into 1,000 subject headings. The collection was initially called “Constance Meade Collection of Ephemeral Printing”, named after his benefactor. It was renamed as the “John Johnson Collection of Printed Ephemera” on its transfer to the Bodleian in 1968. Only about 100,000 items in the collection have been cataloged and fewer digitized.

In his last will dated October 28, 1915, Bellamy mentions that his library is “judged to be the second most complete Philatelic and Postal Library in the Empire if not in the World after that of the late Earl of Crawford”.

As we will see later, Bellamy seems to have gone slow on collecting by the early to mid-1910s. Hence, it’s quite likely that, even in the beginning of the 1910s, his library occupied close to 320 linear feet of space. By early 1908, after the acquisition of the library of Judge Heinrich Fraenkel (1853–1907) of Germany, the Earl of Crawford’s library was close to being at its best and biggest. It then occupied about 270 feet of linear shelf space (Bacon 1908, p.25).

Now, in the context of a modern library, 320 and 270 feet doesn’t seem much. But one needs to keep in mind that philatelic publications of the 19th and early 20th century didn’t occupy as much space; they were usually thin and the magazines short-lived.

The Crawford Catalogue stated in full is: Bibliotheca Lindesiana Vol VII: A Bibliography of the Writings General Special Periodical Forming the Literature of Philately. It was published in 1911 and was meant to be distributed free to public libraries; 200 copies were printed. The same year, the Earl of Crawford gave permission to the Philatelic Literature Society to reprint the catalog. 300 copies were printed titled Catalogue of the Philatelic Library of the Earl of Crawford, K.T. In 1926, came out the Supplement to the Catalogue of the Philatelic Library of The Earl of Crawford, K.T. Published 1911. This was an edition of 200 copies.

Finally in 1938, Addenda to the “Supplement to the Catalogue of the Philatelic Library of The Earl of Crawford, K.T., an 8-page booklet, was published as a supplement to The London Philatelist of March 1938. All of them were compiled/authored by one of the greatest philatelists of all time, Edward Denny Bacon.

In his introduction to the Crawford Catalogue, the Earl stated that he didn’t possess every one of the rare philatelic works in existence but wanted his catalog to describe all of them. Bacon, the compiler, relied on friendly collectors for their help; one of those named is Bellamy. Hence, there is no doubt that Bellamy would have given inputs to Bacon during the preparation of the main catalog of 1911 as well.

Bellamy doesn’t categorize these books as those on philately but uses a rather broad term of “postal history” i.e. books of all nature connected with the post office and postal systems.

At another place, in the same letter, he says that his library also has road-books of pre-railroad days, Acts and Postal Proclamations, etc. from about 1500.

According to Francis Hugh Vallancey, Bellamy’s collection was padded with much that was “just waste paper.” Cited in Philatelic Literature by James Negus (p.215). Perhaps Vallancey was referring to the philatelic ephemera of advertisements, newspaper clippings, prospectuses, society reports, etc. that Bellamy had in his collection.

This is according to a letter dated 1892 to E.W.B. Nicholson, a founder member of the society and later librarian of Bodley. Cited in Oxford Philatelic Society: A History, by A.M. Hughes (p.46).

Bellamy states in his last will dated October 28, 1915: “I wish the University of Oxford to accept these two collections as a permanent expression of my thanks in bestowing upon me the honorary degree of Master of Arts.” At this time, the two collections that he wished to gift were his postal history library and his collection of college stamps.

In the codicil to his will, Bellamy says that he made an offer of his “very large collection of photographic negatives of Oxford and neighbourhood” to the university five or six years prior but the offer was “transferred to the Vice Chancellor to Doctor D.G. Hogarth who in turn so apathetically transferred, shelved and ignored the offer” and also publicly and privately insulted him and his subject of postal history in a letter to The Times of July 14, 1925. Reading between the lines, I get the impression that Bellamy felt it was Hogarth who had orchestrated the rejection by Oxford university. David George Hogarth (1862-1927) was an influential Oxfordian and keeper of the university’s Ashmolean Museum.

In his codicil, Bellamy doesn’t make it clear if Oxford university has rejected his gift or not. But he makes alternative arrangements if the university did so. The timing of the codicil and the vehemence of his words makes me believe that Bellamy drafted the codicil just after receiving the rejection. Further, despite the snub, he still hoped for the university’s acceptance at some later date; hence all the “ifs”.

Bellamy’s interleaved copy of the Crawford Catalogue is now in the Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum, courtesy a bequest of that great American bibliophile, George Townsend Turner (1906-1979). Part II of the catalog dealing with journals can be read online. As per emails exchanged with the Smithsonian, Part I is supposedly on the shelves.

Sir Rowland Hill (1795-1879) is generally credited as the inventor of the postage stamp. In the late 19th century, Patrick J. Chalmers (1819-1891) tried to propagate the idea that his father, James Chalmers (1782-1853) was the real inventor of stamps. To further his claim, he brought out several pamphlets and wrote numerous letters to newspapers, public figures, and philatelists. Pearson Hill, Rowland Hill’s son, did his own bit to refute Chalmers. All these constitute the Chalmers-Hills papers.

Hugely enjoyed reading this piece, which is based on diligent original research. Looking forward to reading your future articles. Best regards, Tim Huxley