Wreck of the SS Ava and the Unlucky William Farquhar

Sad endings for both the steamship and the man

This article was first published as “The Ava Wreck and the other, unknown, William Farquhar.” The London Philatelist, The Story Behind the Cover No. 20, 130, whole number 1491 (December 2021): 562-64.

Now, it has been expanded including by the addition of images not in the original. As also links for further reading and videos for watching! Don’t forget to see the endnotes.

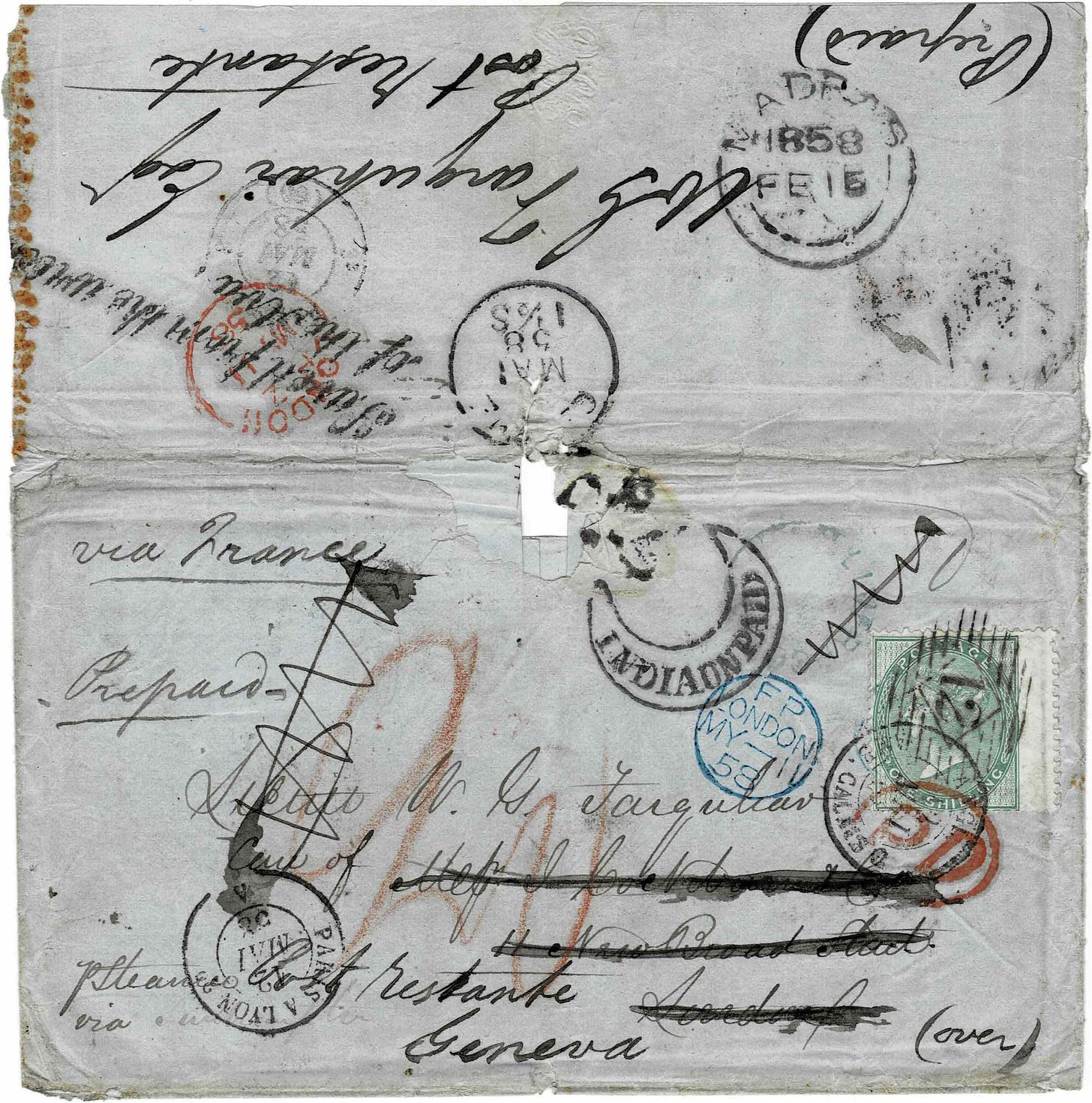

Some time back an item of postal history (Figure 1) appeared at an Argyll Etkin1 auction. While it was a wreck cover, the most interesting point of it for me was the redirection. Not too many such covers, given the perilous state that they are already in, are redirected and that too to a different country.

An examination of the inside of the cover, rather a letter sheet, showed a dateline of 6 October 1858 and it being a statement of account balance of a bank or loan company. Apparently, a sum of Company Rupees 5,725.40 was lying to the credit of the addressee, one Lieutenant W. G. Farquhar.

Wondering who he might be and what an Indian army office was doing in Geneva, I started some research. Given the wonderous possibilities offered by online resources, in about four hours, I had stumbled upon his story – a story as fascinating as nondescript, a story which categorically disproves the adage “Like father, like son.”

Most of the minute details of W. G. Farquhar’s life is known to us from his preserved diary and the many tender and affectionate letters that he wrote to his sisters from 1847 to 1860. These letters were found by Morag Sutcliffe, the great-granddaughter of his sister Amelia Farquhar (later Lumsden), and was transcribed by David F. Sangster, Amelia’s great-grandson in 2013.2 They infuse flesh and life and colour to the otherwise ordinary and mundane lives led by most people, then and now!

William Farquhar and William Grant Farquhar

William Grant Farquhar (hereinafter referred to as William) was the first child and son of Major-General William Farquhar (1774-1839), a Scottish employee of the East India Company (Figure 2).

The senior Farquhar is best known as the person who helped found the British settlement on the island of Singapore and was the first British Resident and Commandant of Singapore from 1819-1823.

Farquhar’s run-ins with Sir Stamford Raffles, the Lieutenant-Governor of Bencoolen and the founder of modern Singapore (who dismissed him) and later with Raffles’ widow, are well-known; the subject, though interesting and complicated, is beyond the scope of this article.3 Perhaps history has given Farquhar a raw deal. Readers interested to inquire into this may want to read this and this first.

Now back in Scotland, Farquhar settled in Perth and married Margaret Loban in 1828.4

Their first child and son born on 19 February 1829 was William Grant (Figure 3). Four daughters followed including Amelia (b. 1833); Amelia was the only sibling who lived long into 1914, the others were dead by 1860.

The senior Farquhar died in 1839 and when Margaret passed away in 1844, the young Farquhar siblings were left orphans. Money was a problem, with not much coming from Farquhar’s estate due to the failure of his agents in Calcutta and London.5 After boarding in school for a few years, they were given a home at their cousin’s place in Edinburgh in 1848. Meanwhile, William enrolled himself as a cadet in the East India Company’s army and passed his public examination on 12 December 1845. He joined the First Regiment of the Madras Native Infantry in 1846 as 2nd Ensign, a rank effective from the date he passed the examination. Subsequently, on 30 October 1848, he purchased his Lieutenancy for about Rs. 1,350.6

In the first few years, he served at various places in South India. Later in September 1852, he was posted to Burma. He remained there till December 1855 and the beginning of 1856 saw him back in Madras. He finally got his much-looked forward to furlough and sailed to Britain in August 1857. The mutiny had started a few months earlier in May but its impact down South was minimal; for example, none of the 52 Madras regiments ever revolted.

William spent some six months at home before he took a tour of the Continent with his brother officer, James George Roche Forlong. They visited Paris, Naples, Rome, Florence, Milan, and Geneva before returning. By October 1858, William was back in a ship sailing back to Calcutta. On 24 March 1860, when in Hoshangabad, a town in the central provinces, he met an untimely death due to cholera. He was just 32.

Looking back, the contrast between his father’s achievements and his could not be greater. In his many years in the army, he saw little promotion; he had advanced just 4 steps in 10 years and was only 8th Lieutenant by late 1856. While hard work and talent are necessary ingredients for success, so are getting the right opportunities and a great deal of luck. Recognising the passing time and his stagnation, a diary entry from October 1856 reads, “I suppose the sun will come some of these days but it can’t make me lucky - the day has gone by.”

On his death, a couple of Scottish newspapers carried the news in just a couple of lines. Buried in Hoshangabad Cemetery, his tombstone reads a simple, “Erected by his Brother Officers as a mark of their esteem.”7 Like most people, he has faded into obscurity.

Wreck of the Ava

The Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company’s (P&O) Ava8 was an iron screw steamer of 1,620 tons (restated in 1857 to 1,373 tons) with engines of 1,056 iHP (320 HP) built in 1855 by Tod & McGregor in Glasgow.9 She left Calcutta at 9.15 AM on 10 February 1858 carrying on board about 240 persons (a few of them embarked at Madras) including some 40 army officers, a number of them distinguished and many wounded, and 25 women and 19 children, many of whom were refugees of the Indian Mutiny including those of the Siege of Lucknow.10

On 14 February at 3.20 PM, the Ava arrived at Madras. She would have picked up this particular cover amongst others; a Madras date stamp of 15 February confirms. She left that port at 4 PM on the latter date.

The next stop on this route would normally have been Point de Galle on the southwest tip of Ceylon (Figure 4). However, she has been asked by the Government to drop about £5,000 of the £253,000 of specie that she picked up at Madras at Trincomalee, a port city in northeast Ceylon; under their contract with the P&O, the government had the right to direct any of the steamers to call at other intermediate ports.11

At 7.55 PM on 16 February, some 12 miles away from her destination, she hit the rocks on ridge extending three-quarters of a mile from shore, off Rocky Point, about a mile-and-a-half to the northwest of Pigeon Island. Her passengers were put on boats and some rescued the next morning by local boats; they reached Trincomalee the afternoon of 17 February. Fortunately, there was no loss of life.12

Most of the cargo including the specie and 64 boxes of mails (each box being about 2’ X 1’ x 1½’ deep) were rescued by the crew of the HMS Chesapeake and local divers over the next few weeks. The mails were bought to Galle by HMS Pylades on 18 March. On the same day, one smaller batch of mails, presumably such mails which were relatively dry, were put onboard the P&O Candia (18.3) which sailed to Suez (2.4) via Aden.

At Suez, the mails were offloaded, moved overland to Alexandria, and transferred to P&O Pera (4.4) which subsequently reached Southampton (17.4) and thereafter reached London (18.04); these letters usually have a date stamp of 19-20 April.13 The next tranche was carried by P&O Hindostan (2.4) to Suez (18.4) and then by the P&O Colombo from Alexandria (20.4) to Southampton (10.5);14 this set of mails have a London date stamp of 11 May.

As is customary with survivors of this wreck, two lines in cursive script, Saved from the Wreck / of the Ava (Figure 5) was handstamped on all letters at the Foreign Branch Office of the London G.P.O. This is “the first mishap from which collectors can reasonably hope to acquire a cover with a wreck cachet.”

The redirected cover

On 11 May, the day the cover arrived in London, William’s agent, J. Cockburn & Co., of 11 New Broad Street London, franked it with an 1856 one shilling green (SG 72?) and dispatched it onward to Geneva picking up handstamps of Liverpool St., Calais, and Paris to Lyon railway on the way. Given that the addressee was on a holiday, it was marked Poste Restante, a service offered by the post office whereby mail is kept for some period until collected.

The East-India Register and Army List for 1858 confirms that William was on furlough at this time (Figure 6) but it does not answer the Geneva puzzle. It is from his letters that we can so clearly trace his movements. William reached Geneva on 12 May 1858 and this letter followed him there likely on 13 May (Figure 7); the Geneva postmark does not show a date but shows a time of 1½ S for 1.30 PM. Obviously, William and his agent were in regular touch so that the latter knew where to redirect it.

From a rates perspective, the letter was sent unpaid as evidenced by the INDIA UNPAID crescent stamp. The manuscript “6” reflects the postage due of 6d on delivery; 6d being the then steam postage between Great Britain and India. Though sent unpaid, there was no fine applicable on such bearing letters until 1 September 1858.15 On the upper right is “1d”, the credit due to India of the 6d collected by the British post office. Both “6” and “1d” have been struck through, likely by the sender while redirecting. The one shilling stamp correctly paid the current rate from Britain to Switzerland via France.

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank David F. Sangster for going through a draft of this article and providing me with a photo of William Grant and his Geneva letter. I also thank Jean Voruz for helping me with the Geneva postmark on the redirected cover. Any feedback can be sent to my email id: abbh [at] hotmail [dot] com.

Lot no. 359 in auction held on 2 October 2020.

The letters and diary entries can be seen and downloaded from here: https://www.myheritage.com/site-141143171/morison-farquhar-dingwall-fordyce-others. Accessed 21 December 2020.

In September 2019, the descendants of Raffles and Farquhar met for the first time in almost 200 years at the bicentennial-themed exhibition at the National Museum in Singapore, for which they loaned their personal collections. The Straits Times, Singapore’s preeminent English newspaper, reported that they seemed to “maintain some distance!”

While in the Straits, Farquhar had at least six children through his mistress Antoinette “Nonio” Clement, a Malaccan woman of French-Malay descent. Their first daughter, Esther Farquhar Bernard, is the great-great-great-great-grandmother of the current Canadian Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau.

Extracts from William Farquhar’s will can be found on the website of the National Records of Scotland: https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/research/learning/hall-of-fame/hall-of-fame-a-z/farquhar-william. Accessed 30 January 2021.

The purchase of commissions in the East India Company as well as the British army was the common practice of an officer paying money to buy into a more senior post in the regiment as William does in 1849 when he purchases his Lieutenancy after three years’ service as Ensign.

Crofton, O. S. List of Inscriptions on Tombs or Monuments in the Central Provinces and Berar. Nagpur: Government Printing, C. P. 1932.

Ava or Inwa was the ancient capital of Burma. Information in the part of the article has been taken from (1) Hopkins, A. E. A History of Wreck Covers Originating at Sea, on Land and in the Air. 3rd ed. London: Robson Lowe Ltd., 1967; (2) Hoggarth, Norman, and Robin Gwynn. Maritime Disaster Mail: A Study of Mail Salvaged from Maritime Disasters, as Casualties of War, Collisions, Fires, Shipwrecks and Stranding. Bristol, Great Britain: Stuart Rossiter Trust Fund, 2004; (3) Ford, Eric H. “Saved from the Wreck of the “Ava”.” India’s Stamp Journal 15 no. 11 (November 1952): 251-254; and (4) Kirk, R. The P&O Lines to the Far East. Vol. 2. 4 vols. British Maritime Postal History. Heathfield, East Sussex: Proud-Bailey Co. Ltd., 1982. Further, the official report of the two-member court of investigation constituted by the Board of Trade to inquire into the loss, contemporary newspapers, and online resources have been referred to and some of the earlier information published in the first two books above have been corrected.

Ominously in her maiden voyage from Southampton to Alexandria in August 1855, she broke a screw blade and had to be towed to Malta.

Among the refugees and passengers was Lady Julia Inglis, wife of (later) Major-General Sir John Inglis, commander of the British troops at the Lucknow residency, and their three children. She kept a dairy which was published as The Siege of Lucknow: A Diary in 1892; the book also contains her experiences with this wreck.

Clause 38 of the Contract between the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company and the Commissioners for executing the office of Lord High Admiral of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland dated (and effective) 1 January 1853. This contract included the conveying the mails from Calcutta to Suez via Galle but not from Bombay to Aden; the latter was a separate contract of 1854.

The investigators held Captain Cooper Kirton (1828-1915) of being in default for the loss of the vessel by not following standard procedures. The Board of Trade suspended his Certificate of Competency as Master, issued just 15 months earlier on 6 November 1856, for six months. After the suspension, Kirton was awarded with a post in Malta as P&O’s representative. He worked for P&O until 1902. Interestingly, Lady Inglis (see note above) records Kirton’s first exclamation when the ship struck as, “Oh! My poor father!”

Surprisingly, the British newspapers of that period contain no news about the first of rescued mails being received. They were expecting the P&O Ripon to carry them and arrive around 26 April.

P&O Colombo arrived in Malta on 23 April and left the next day. But she had to come back the following day for engine repairs. Further, she herself was wrecked on Minicoy Island, the southernmost of the Laccadive chain in the Indian Ocean, on 19 November 1862.

Treasury Warrant dated 13 August 1858 published in The London Gazette of 17 August 1858.