This article was first published as “Wreck of the SS Alma, June 1859.” India Post 55 no. 4 whole no. 221 (October – December 2021). India Post is the journal of the India Study Circle for Philately.

It was republished as “Wreck of the SS Alma, 1859″ in La Catastrophe 28 whole no. 106 (June 2022) and whole no. 110 (June 2023). La Catastrophe is the journal of the Wreck & Crash Mail Society.

The Steam Ship (SS) Alma was built by John Laird, Sons & Co. in Birkenhead, a town near to Liverpool, and was the first ship for the Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P&O) from the yard. She was launched on 12 July 1854 as Pera,1 the name referring to an area in Constantinople (present day Istanbul). On 19 March 1855, she was registered as Alma; her name was changed because of popular enthusiasm following the Battle of Alma in the Crimean War the previous September wherein the allies made up of British, French, and Egyptian forces defeated the Russian one.2

Alma was an iron screw steamer with gross and net tonnage of 2,220 (reinstated in 1857 to 2,164) and 1,294 tons respectively. She was powered by oscillating geared steam engine of 1,445 ihp or 450 hp. Her maiden voyage was on 5 April 1855 on the Liverpool-Portsmouth-Constantinople-Crimea route carrying 60 officers and 1,390 men to the Crimean War. In October 1855, she was released for commercial service and in December she made her first commercial voyage on the Southampton-Alexandria route. In June 1856, she left Southampton to take up station at Calcutta and work on the Calcutta Line (Calcutta-Suez); she did so until she was wrecked in June 1859 (Figure 1).

The Wreck

The P&O Alma3 and was commanded by Captain George Fitzgerald Henry4 who held a master’s certificate of competency dated 23 May 1857. He had been in the P&O’s service for many years and had made 72 voyages in the Red Sea. William Henry Davies,5 the first officer, had made 11 voyages in the Red Sea. There were four other officers and a crew of 51 Europeans (chiefly engineers, stewards &c) and 171 Manilla men and Lascars. There were about 140 passengers, among whom was Sir John Bowring.6 The India and (later at Galle) China (mostly from Hong Kong) mails were also on board, and a cargo worth £200,000. There was also on board an Arab pilot of the Red Sea of the name of Bushier, who it was stated was engaged merely for the satisfaction of the insurers, and the captain and officers never sought and habitually disregarded his advice.7

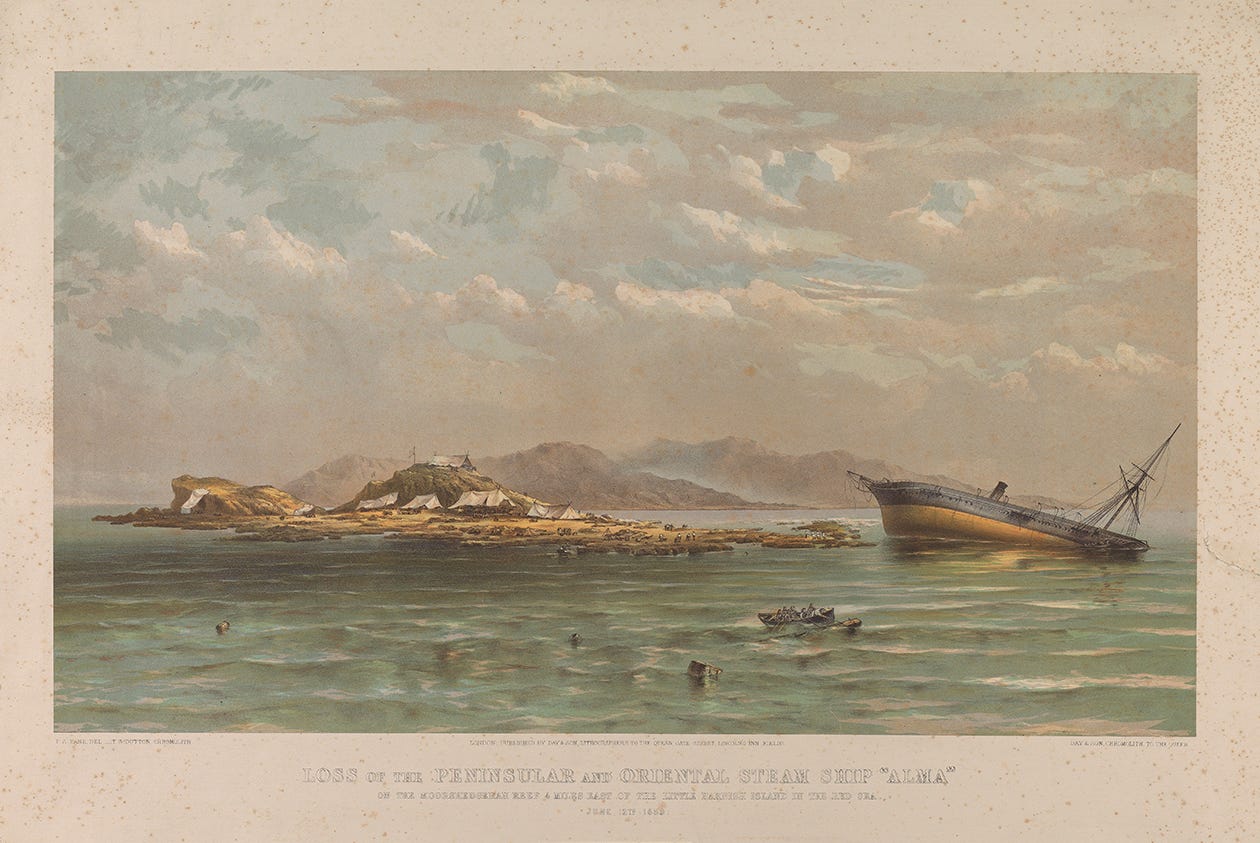

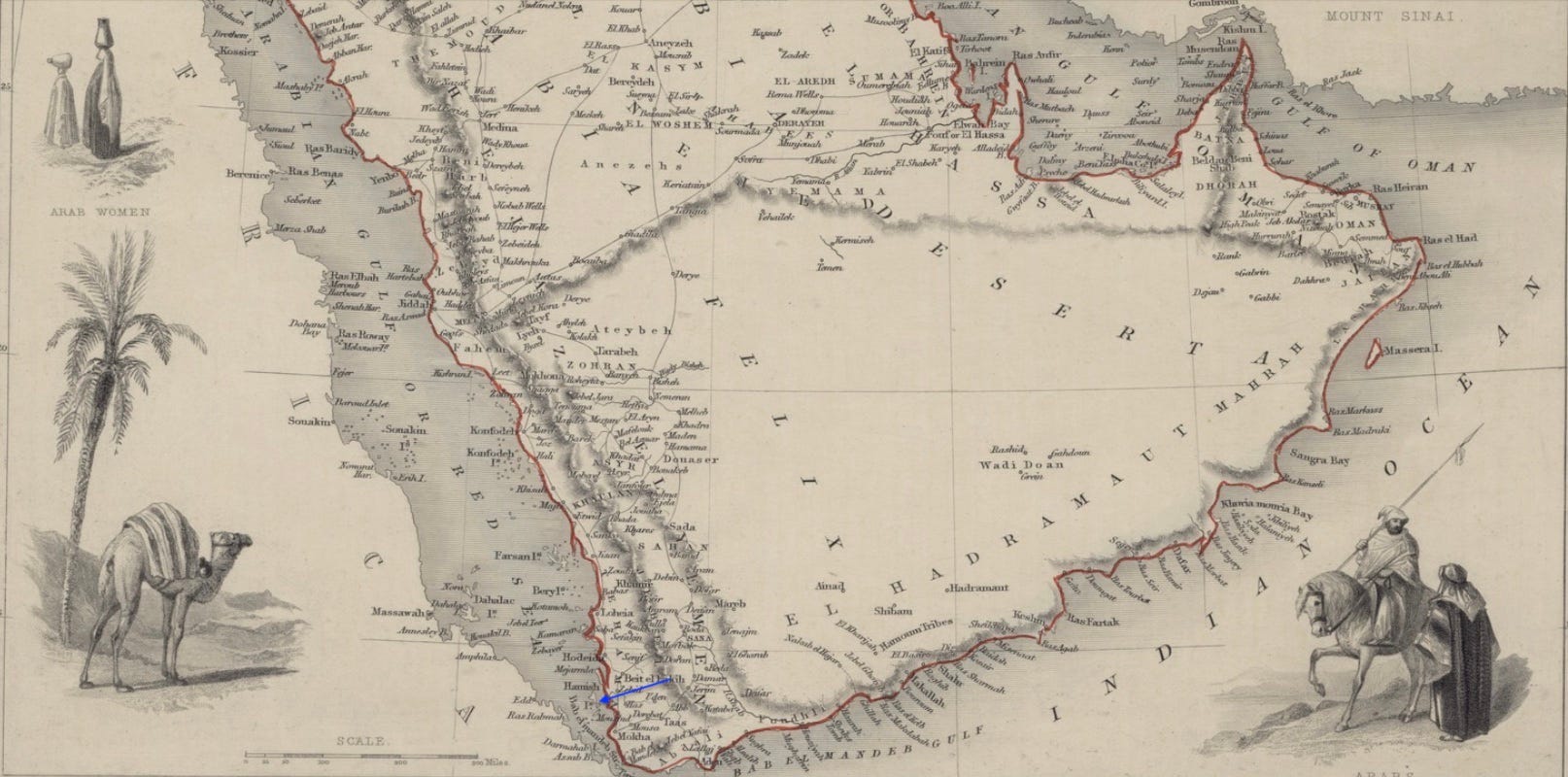

Alma left Calcutta on 18 May and made her usual intermediate stops at Madras (23/24.05), Galle (27/28.05), and Aden (10.06). She left the latter on 11th June at 5.50 AM for Suez. At this time Captain Henry was confined to his cot, by an attack of erysipelas (bacterial infection of the skin), and Davies, was left in charge. On 12 June at around 3.00 AM, she was wrecked on the Mooshedjerah (or Mooshedgerah / Musejara) Reef, four miles off Little Harnish (or Haruish) Islands, 112 km (70 miles) north of Perim in the Red Sea. (Figure 2)

As soon as the ship had struck, it was found that the reef formed part of an island. The passengers were conveyed in boats to this island and there was no loss of life. The island was uninhabited, sterile, and a waterless waste. Only a small quantity of provisions, some beer and wine, and a very small quantity of water were saved. A boat was at once manned under J Baker, the second officer, and Newall, the contractor for the Red Sea Telegraph Cable, and dispatched to Mokha (Mocha) about 30 miles away, for assistance. They reached Mocha the next day and the Turkish authorities were prompt in dispatching aid, though it did not arrive before HMS Cyclops did.

The boat then proceeded by sea to Aden where HMS Furious and Cyclops had been in harbour when the Alma had left. Further, Newall knew that the latter was expected to sail out on 13 June in order to revisit all the stations on the Red Sea and take some further soundings on the line of the newly laid telegraph cables between Suez and Aden. On 14 June about noon the Cyclops, under Captain WTL Pullen, was caught around ten miles south of Perim; she steamed instantly to the wreck.

By this time the provisions and water had begun to run short, the island was surrounded by numerous fishing boats of the savage and piratical Arabs, and the Lascar seamen were showing symptoms of mutiny. In this gloomy state of affairs, the Cyclops made her appearance at about half-past-six on the morning of the 15th, and soon removed the people from the island. During the three days and some hours they had been on the reef they had been exposed to much suffering; many were struck by coups-de-soleil (sunburn as the temperature reached 110 degrees Fahrenheit or 43 degrees Celsius in the shade), and the purser, Hatchet, died from the effects.

The wreck remained some time upon the reef, but ultimately went to pieces. As was usual, an investigation into the wreck was made. On 17 October 1859, the Board of Trade held Davies to blame and his certificate of competency was suspended for 12 months.

Recovery of the Mails

HMS Cyclops carried the passengers and mails from the wreck back to Aden.8 P&O Bombay, which was carrying the India mails from Bombay, ferried the mails from Aden (18.06) to Suez (25.06). The mails reached Alexandria the next day.

All mails for Great Britain and France were put aboard P&O Pera. She left Alexandria (26.06) and reached Southampton (09.07) via Malta (30.06; arrived 00:45 and left 12.30) and Gibraltar (04.07). Mails reached the London GPO the same day.

Whilst aboard the Pera, the Mediterranean sorters sorted both the mails routed via Southampton as well as those via Marseilles; the latter was done between Alexandria and Malta. However, this was not the usual sorting procedure;9 an unexpected situation had arisen. The Austrian government withdrew the Austrian Lloyd steamer from the Trieste Line, presumably due to the outbreak of the Austro-Sardinian War.10 Hence Robert Thorne (Thorn in some other references), Packet Agent at Alexandria, sent the European mails, which would otherwise have gone via Trieste, to London via Marseilles. Pera, the larger ship (2,104 tons), carried the English and French mails, both via Southampton and via Marseilles as well as the majority of the passengers. P&O Ellora (1,574 tons) carried the Trieste mails to Marseilles apart from 26 passengers.

Ellora, which had left Alexandria (26.06) at around the same time as Pera, picked up the bags containing the sorted mails at Malta (30.06; arrived 13.25 and departed 17.35) where they had been left earlier that day and sailed for Marseilles (03.07). The mails went overland across France and the English Channel to reach the London GPO two days later (05.07).

The sailing details are summarised in Table 1.

Postal History

Until the mid to late 1980s, it was thought by postal historians that there were no mail survivors from this wreck. Adrian Hopkins does not cover it in his famous book on wreck mails.11 Reg Kirk mentions in his work on the P&O Lines to the Far East that the mails of the Alma were lost.12

This is strange since contemporary newspapers clearly state that the mails were saved. Perhaps the lack of a wreck cachet, usually prepared and applied on damaged mails, made it difficult for collectors and researchers to correctly identify and thus save the covers carried by the Alma on her ill-fated journey. This may also account for the scarcity of the covers of this wreck as compared to other wrecks of that time period; for example, the P&O Ava13 the previous year or the P&O Colombo in 1862.

As per Lee Scamp,14 the discovery of a cover from Manila (which went via Hong Kong and then on the China Line to Galle where it was put onboard the Alma) prompted Kirk to update this information in one of his future works in 1989.15 In his book and article, Scamp records four covers, all from the Far East. Hoggarth and Gwynn16 likely use this assertion to affirm the number and assign the highest scarcity rating of ‘A’ to this wreck i.e., less than 10 covers known. Another previously unrecorded cover sent from Hong Kong to Stockholm was brought to light in 2018 by Andrew Cheung.17

This article will not concern itself with the Far East mails or sailing schedules. Interested readers may refer to the works of Scamp, Kirk, and Cheung.

Indian mails which travelled on this ill-fated voyage do exist. Perhaps a handful exist and more may be unearthed once collectors go back and look at their covers. Three are presented here.

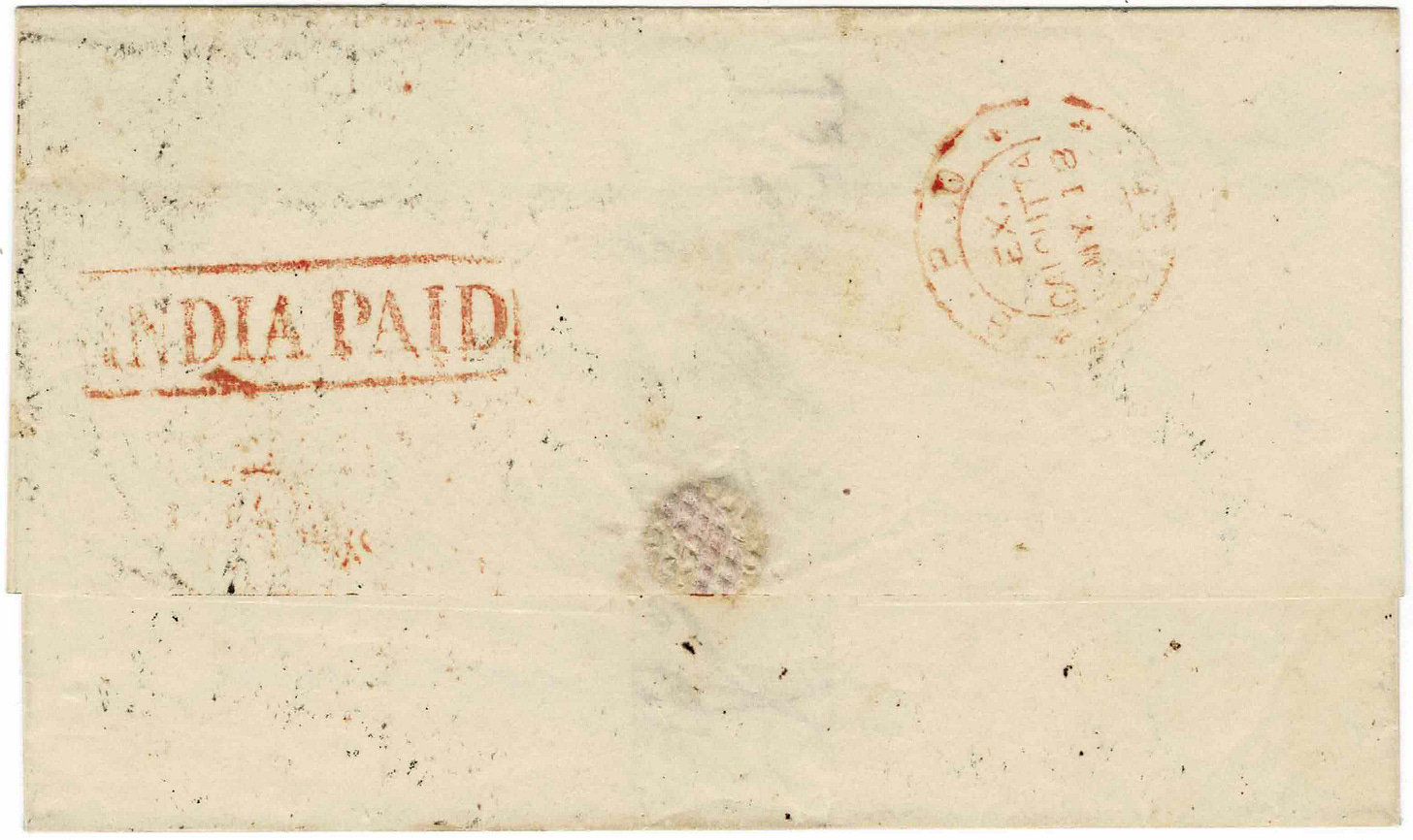

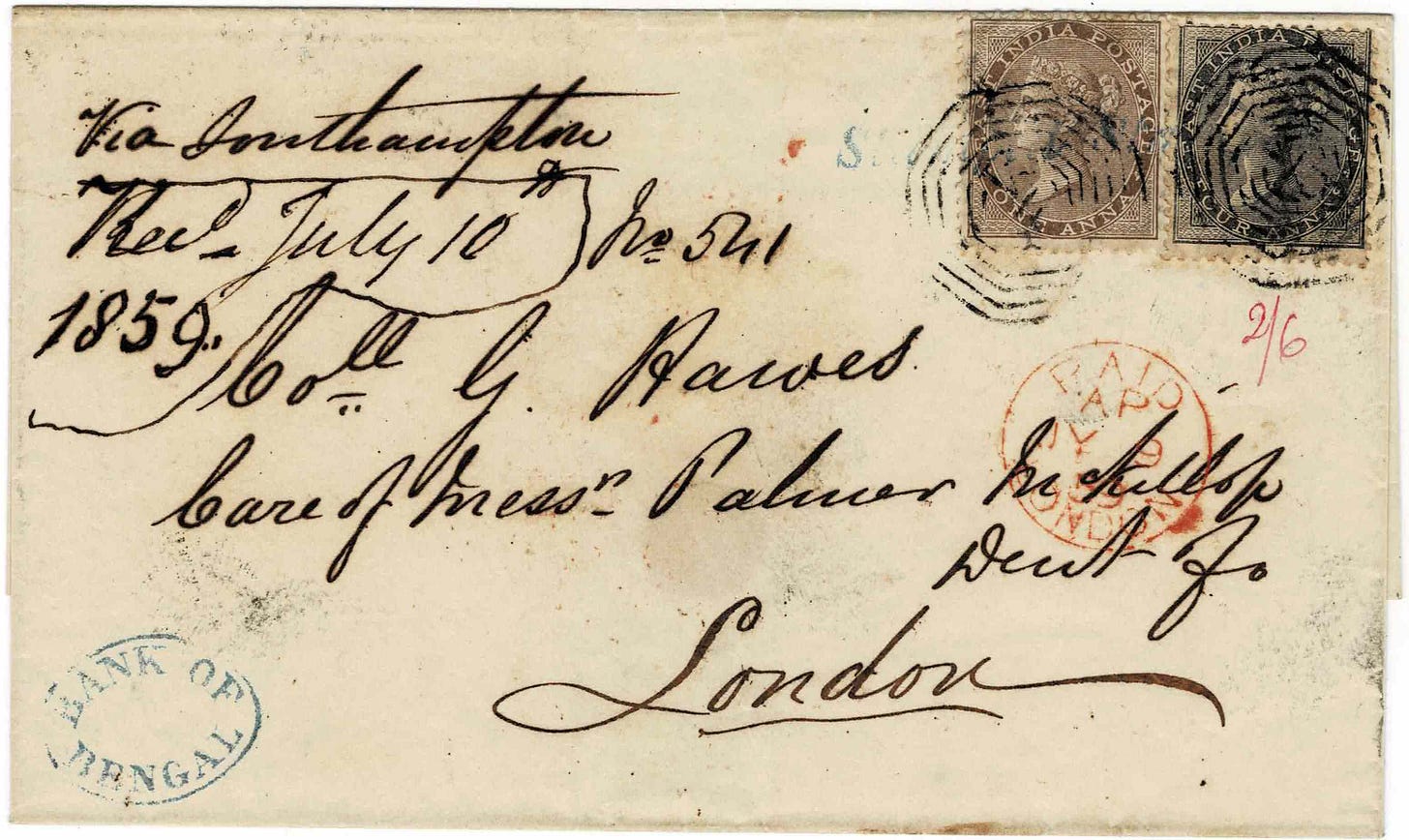

Figure 3 shows an ‘After Packet’ (AP) letter18 sent from Calcutta to Kedgeree via the first AP on 18 May and prepaid 5 annas for the route via Southampton viz. 4 annas (or 6 pence) steam postage for letters weighing up to ½ oz and 1 anna AP fee (equal to the inland rate) for letters weighing between ¼ and ½ tola.

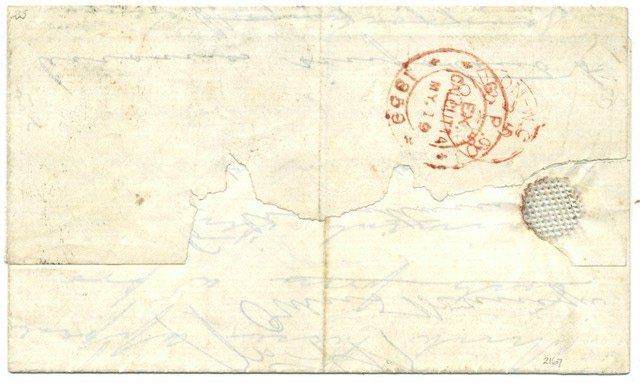

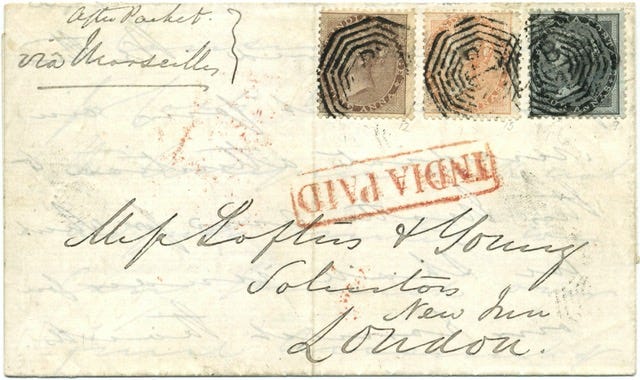

Figure 4 depicts another AP letter sent from Calcutta via the second AP on 19 May stamped 7a for the route via Marseilles i.e. 4a (or 6d) steam postage plus 2a (or 3d) French transit for letters weighing up to ¼ oz and 1a AP fee for letters weighing between ¼ and ½ tola. This cover is also featured in Smith and Johnson.19

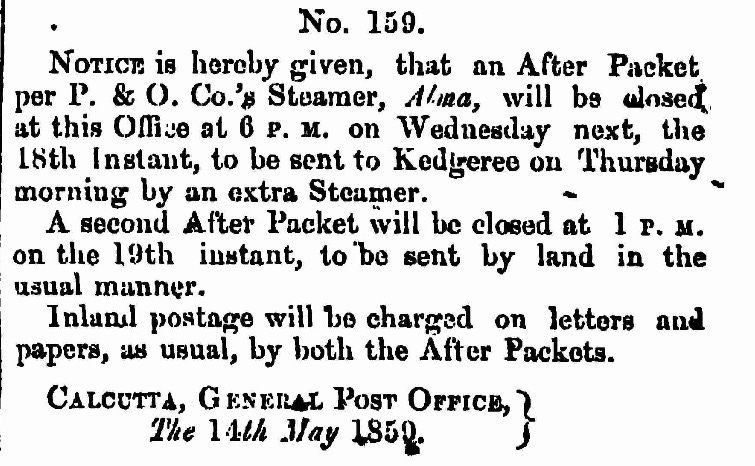

A Calcutta GPO postal notice dated 14 May announcing the said APs is presented as Figure 5; note that acceptance of normal mails had closed on 17 May. It is unusual for two APs to have been made up for one sailing. Further, while dispatch of such packets to Kedgeree on steam tugs likely went on into the 1860s, postal notices after mid-1859 do not usually specify whether the route taken was via water or land.20

Finally, Figure 6 shows a letter from Madras to Cognac, France sent bearing and charged postage due of 16 decimes for letters weighing between 7.5 and 15 gm.21 It was put on board the Alma when she was at Madras on 24 May. It reached Cognac via Marseilles and Bordeaux on 5 July.

Acknowledgements: I thank Max Smith and Martin Hosselmann for permitting use of covers from their collections. I would also like to acknowledge Andrew Cheung who helped me with a couple of articles, including one of his own, on the wreck. Comments or feedback are welcome and may be sent to my email id: abbh [at] hotmail.com.

Pera comes from the old Greek name for the place, Peran en Sykais, literally "the Fig Field on the Other Side."

A few towns in Canada and New Zealand as well as a bridge in Paris were also named after this battle!

It is some coincidence that a ship with the same name Alma, 1187 tons, wrecked just a few days later on 5 June 1859 at the mouth of the River Hooghly. She belonged to M/s John & Thomas Sinclair of Belfast and was on her way from Calcutta to Mauritius with a cargo of rice. Unfortunately, the Captain and his wife and child, the first officer, the pilot, some passengers and their servants, and 14 of the crew drowned.

Henry was later elected Chairman of the newly formed Bombay Municipal Corporation in 1873. He died when thrown from his carriage in 1877. A road in the Colaba area of South Bombay is named after him.

Fate was kind to Davies (1825-1898) as well; he was later one of the founders of the Exchange Telegraph Company and a director in many prosperous companies.

Sir John Bowring (1792-1872) was an English political economist, traveller, writer, literary translator, polyglot, and the fourth Governor of Hong Kong. After a year of scandal and intrigue and weak from arsenic poisoning, he had just left the latter office in May 1859 and was travelling back home; the wreck compounded his misery!

Most of the information in this section has been culled and summarised from news reports, including passenger letters, carried by contemporary newspapers.

Much of the information in this section is taken from Kirk, R. “The Mediterranean Sea Post Office.” In The British Sea Post Offices in the East. Vol. 4. 4 vols. British Maritime Postal History, edited by Edward B. Proud, 9-130. Heathfield, East Sussex: Proud-Bailey Co. Ltd., 2003.

The usual sorting procedure at this time was clarified in a letter from the London GPO to the Postmasters of Gibraltar, Malta, and Southampton dated 5 March 1859: “The Mail Officer and the sorter assisting him, will leave Alexandria by the packet proceeding to Marseilles and will sort the correspondence by that route before the packet reaches Malta. Delivering the Mails for France and England into the charge of the Commander, they will disembark at Malta and await the Packet for Southampton. The correspondence by the route of Southampton will be sorted during the voyage from Malta to that port.”

In India, C. K. Dove, the Post-Master General of Bengal issued a postal notice no. 1694 dated 21 June 1859 mentioning, “The Public are informed, that in consequence of the War which has broken out, the Austrian Packets hitherto plying between Alexandria and Trieste has been withdrawn, and letters, &c. to the United Kingdom or the Continent of Europe cannot be forwarded viá Trieste until further orders, and no Mail for the Austrian Post Office at Alexandria will be made up in future.” The war was short and another post notice dated 19 October 1859 clarified “…that the line of Austrian Packets between Alexandria and Trieste having been re-established, letters can again be forwarded…”

Hopkins, A. E. A History of Wreck Covers Originating at Sea, on Land and in the Air. 3rd ed. London: Robson Lowe Ltd., 1967.

Kirk, R. The P&O Lines to the Far East. Vol. 2. 4 vols. British Maritime Postal History. Heathfield, East Sussex: Proud-Bailey Co. Ltd., 1982 (pp. 47).

It is interesting that when the P&O Ava wrecked in February 1858, she was carrying a spare shaft for the Alma which had broken hers while on route from Calcutta to Suez in December 1857.

Scamp, Lee C. Far East Mail Ship Itineraries: British, India, French, American, and Japanese Mail Ship Schedules 1840-1880. Vol. I. II vols. The Author, 1997 (pp. 257) and Scamp, Lee C. “Saved from the Wreck of the “Alma” (etc).” Hong Kong Philatelic Society Journal no. 2 (1998).

Kirk, R. Australian Mails via Suez 1852 to 1926. Beckenham, Kent: The Postal History Society, 1989 (pp. 60).

Hoggarth, Norman, and Robin Gwynn. Maritime Disaster Mail: A Study of Mail Salvaged from Maritime Disasters, as Casualties of War, Collisions, Fires, Shipwrecks and Stranding. Bristol, Great Britain: Stuart Rossiter Trust Fund, 2004 (pp. 34).

Cheung A. M. T. “Saved from the Wreck of the P&O Alma – A Previously Unrecorded Letter to Sweden.” Hong Kong Study Circle Journal no 386 (July 2018).

An ‘After Packet’ consists of letters accepted from the public, on payment of an additional fee, after the expiry of the time limit for normal mails. While the ship on which the letters are to be sent may have left Calcutta, it would not have been put to sea given the distance of more than 80 miles. Such letters could be sent to Kedgeree, either by water or by land, so that it could still be put on board as the ship passed the mouth of the Hooghly river.

Smith, Max, and Robert Johnson. Express Mail, After Packets, and Late Fees in India Before 1870. Wheathampstead, Herts, UK: Stuart Rossiter Trust, 2007 (pp. 128)

Smith and Johnson, Express Mail, pp 127-128.

It is one of the joys of postal history to figure out how the postage due number was worked out! In this case, the due for single weight letters (single weight being 7.5 gm in France and ½ oz in GB) was the aggregate of: (i) 4 decimes (or 4d) owed by France to GB under the 1857 Anglo-French Postal Convention, (ii) 2 decimes French internal postage, and (iii) 2 decimes French penalty on delivery of unpaid letters, making a total of 8 decimes (or 80 centimes). This being a double weight letter entailed a postage due of 16 decimes (or 1 franc and 60 centimes). See Bohn, Jeffrey C. Franco-British Accountancy Markings on Mails from the Indian Ocean 1843-1875. Indian Ocean Study Circle, 1990.