This article was first published as “Wreck of the ship Albion, 1817″ in India Post 58 no. 1 whole no. 230 (2024). India Post is the journal of the India Study Circle for Philately.

One of the early Indian ship wrecks from which letters have survived is that of the free trader Albion which was wrecked in January 1817.

Built by J. Scott & Co. at Fort Gloster (or Gloucester), Calcutta1 (underlined in Figure 1) for J. Hunter, Albion measured 818 tons,2 and was launched on 12 November 1814. On 13 January 1817, when under the command of Captain J. R. Oliver, she was wrecked off Foul Point about eight miles from Trincomalee harbour.

Leading up to the Wreck

The Albion left Calcutta on 10 November 1816 bound for Great Britain (Madras Courier dated 12 December 1816). She was detained at Saugor Island (underlined in Figure 1) at the mouth of the River Hooghly for longer than expected for taking in cargo and she finally left that place on 26 December (Madras Courier dated 7 January 1817). Arriving at Madras on 4 January 1817, she took on further packets from that place (Figure 2). She left on the 10th intending to dock at both Trincomalee and Colombo to take in “about one hundred time expired Men of His Majesty’s Regiment on Ceylon.”

Reports published in the Madras Courier (dated 4 February 1817) give information on what transpired. The Albion experienced rainy and squally weather with a heavy sea after she left the Madras roads. This caused the ship to plunge deeply and make a great deal of water. On the 12th at day break, they saw Pigeon Island, and it was intended to land some part of the cargo to lighten the ship. The same night, a sudden squall struck the ship and carried away her fore-top-mast, which rendered it necessary to stand into the Bay for soundings and she came to an anchor in 8 fathoms. The night throughout was squally, which kept the people constantly at the pumps. On the 13th noon, sail was made upon her and an endeavour made to get into the harbour, but after many tacks, &c. the ship again struck so heavily, and held the ground fore and aft so strong, that it was found necessary to cut away the main and misen masts. To save her was impossible. The most prompt measures were adopted for the preservation of the passengers, which was considerably assisted and improved by the exertions of the Officers of His Majesty’s ships lying in Trincomalee harbour. While no lives were lost, the cargo and baggage went to the bottom (Figure 3). The packets were preserved and taken to Madras quite likely on HMS Magicienne.

Letter(s) from the Wreck

The Government Gazette of 6 February 1817 carried a notice dated 31 January 1817 issued by the Post Master General of the Madras GPO, Mr. E. R. Sullivan (note that Sullivan had also been appointed as His Majesty’s Deputy Post Master General under the terms of the India Packet Letter Act of 1815 and used either of the designations while signing post office notices).

Notice is hereby given, that the Packet for England, which was forwarded on the Ship Albion, has been returned to this Office (having being saved from the wreck of that Ship), together with the Packet which was intended for the Java.

The Letters, (generally speaking) are from the damp, &c. not in a state to be again forwarded to England – Any Person therefore may have Letters returned to them on specifying their address, in writing, to the Post Master General.

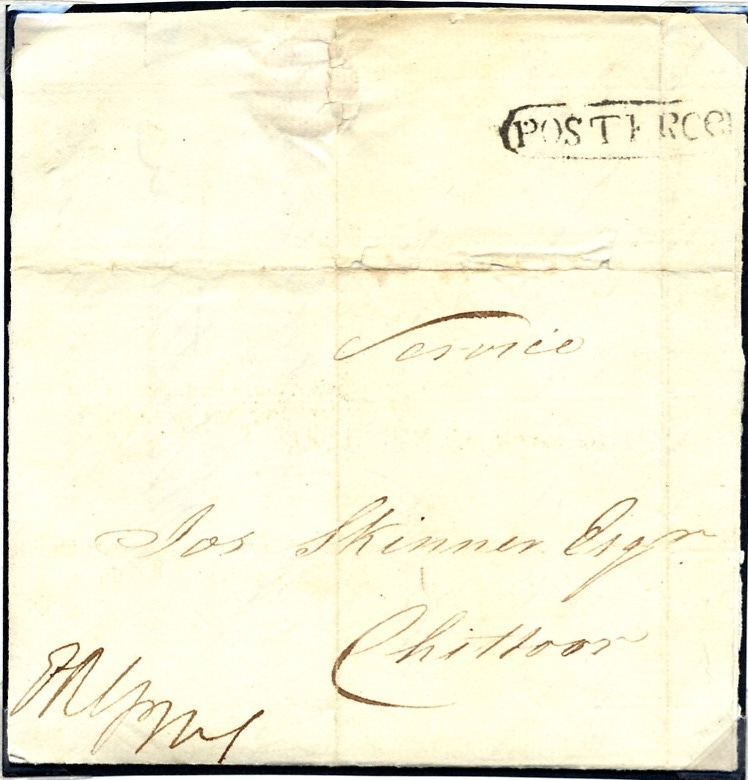

For instance, in his letter dated 3 February 1817, one Jos Skinner of Chittoor (on behalf of Major Thomas de Havilland) applied to the post office for three letters to be returned. These were enclosed in a letter sent by Sullivan to Skinner on 12 February 1817 (Figure 4).

Not everyone would have collected their letters with such alacrity. Therefore, in the Government Gazette of 13 March, Sullivan published a long list of letters saved from the wreck and yet remaining unclaimed at the GPO; an extract appears in Figure 5.

What happened to letters which were put on board the Albion at Calcutta? Were they returned to the Calcutta GPO? Or were they destroyed by the Madras postal authorities since the cost of sending them back would have been too high?

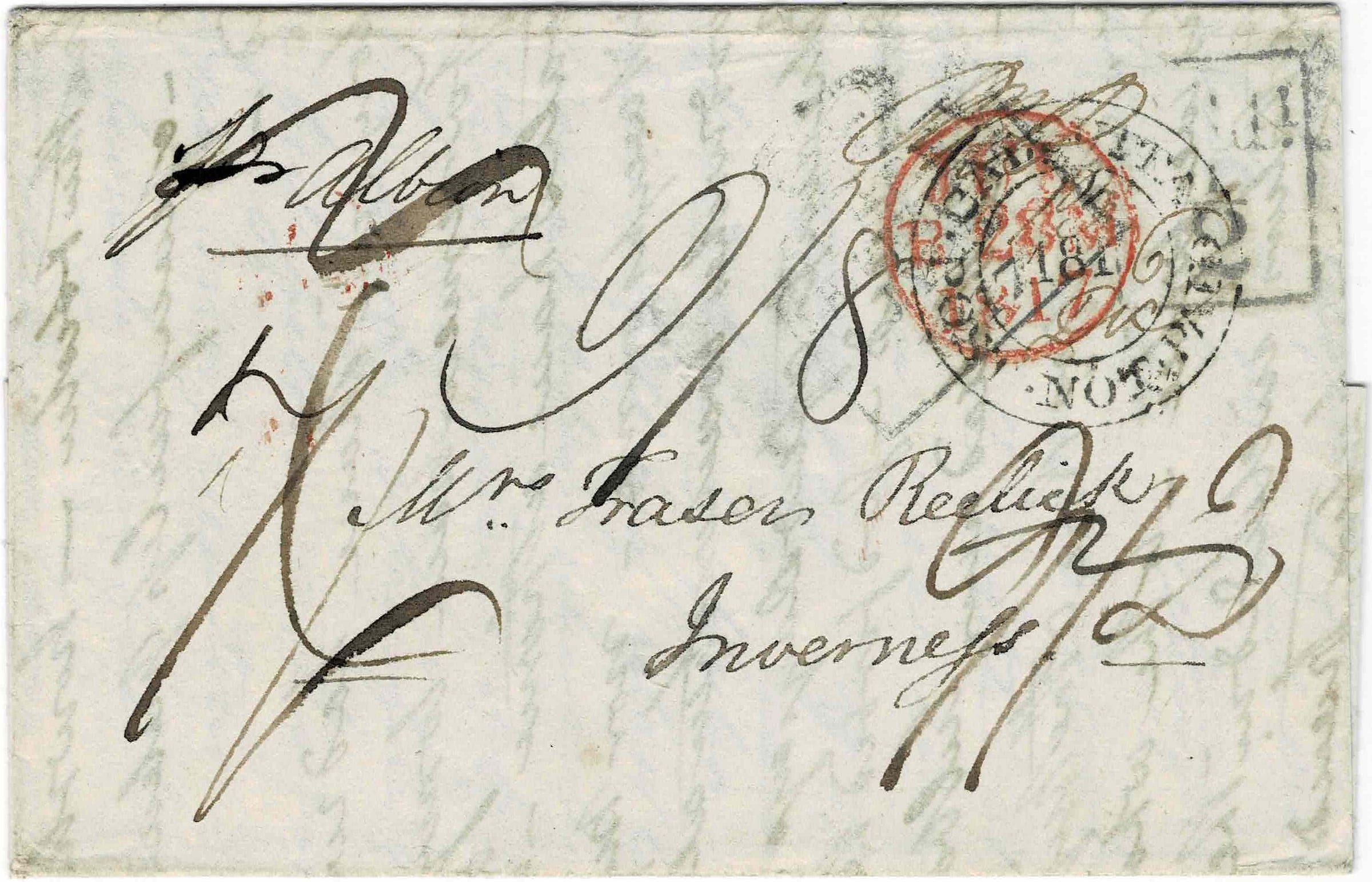

Evidence from one letter (Figure 6) posted at Calcutta on 13 December 1816 indicates that at least some of them, perhaps the ones in good condition, were forwarded to GB.

There are a number of interesting points to note with respect to this letter:

It was sent during the so-called ‘King’s Post’ period i.e. when the India Packet Letter Act 1815 (55 Geo 3 c.153, 11th July 1815) was in operation. It was considered as a Ship Letter at Calcutta as the CALCUTTA PACKET LETTER (Giles SD7) mark is absent. Further, as evidenced by the CALCUTTA / {13} / 181{6} / {Dec} / POST NOT PAID (Giles SD6) handstamp, sea postage to Great Britain (GB) wasn’t paid by the sender and was supposed to be collected from the recipient.

It’s most likely an ‘After Packet’ letter. The Albion had left Calcutta on 10 November and this letter, posted more than a month later, would have been sent as an After Packet to catch her before she sailed out to sea. There are no manuscript rate marks on the letter evidencing collection of any After Packet rate; however, it’s probable that 5a being the inland rate to Kedgeree (underlined in Figure 1) was collected.3

The postage due of 9/8 i.e. 9s8d indicates it was treated by the London GPO not as a ship letter but as a packet letter (since it was a double letter, twice the 3s6d packet rate plus 1s4d inland postage for the distance from London to Inverness via Edinburgh). This could have been because it was brought to GB in a ship (HCS Batavia) considered by the British postal authorities to be a packet and not a private ship.

Finally, the faint and unrecorded handstamp {Crown} / FREE / SHIP LETTER / JY 25 / 1817 can be seen under the red circular Edinburgh datestamp. Usually FREE stamps were applied in GB on letters sent to the East India Company’s chairman or board of directors, which isn’t the case here. Hence, this stamp’s application in London on a letter to someone not connected with the Company is strange; perhaps an error?

Not the wrecked Albion

‘Albion’ is an archaic name of Britain. For this reason, there were a number of ships around that time, private as well as those of the East India Company,4 which were named so. Forget postal historians of today, even people of those days were liable to get confused! (Figure 7)

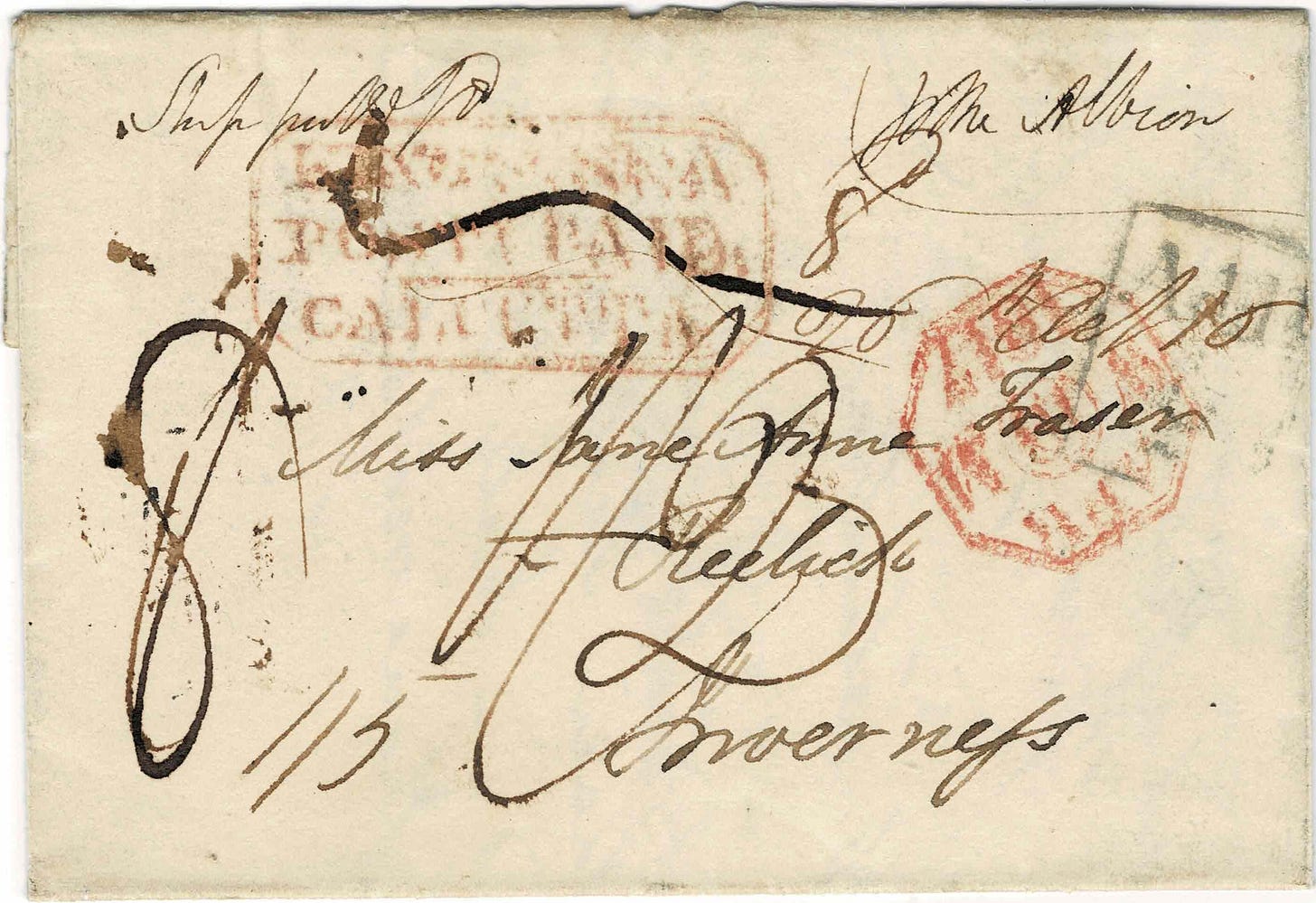

Illustrated in Figure 8 is a letter from the same Fraser correspondence. Posted on 26 October 1816 (see manuscript ‘26th Oct 16’), it’s endorsed ‘p(er) the Albion’. This is not the Albion which was wrecked but a different one. Weighing 488 tons, she was built by George Hillhouse & Sone, Bristol for R. Kidd & Co. and launched in 1813. Her masters had obtained a license to sail to India from the East India Company and she was then commanded by Captain W. Fischer.

Again, this letter was sent during the ‘King’s Post’ period. Unlike the previous letter, this single letter prepaid 8d (or 4a9p in Bengal currency) sea postage for letters carried by private ships; see manuscript ‘Ship postge pd’ top left and ‘8d’ to the right of the red KING’S. SEA / POSTE. PAID. / CALCUTTA (Giles SD5). Due to an incorrect reading of the 1815 Act, the Calcutta GPO erroneously allowed prepayment of postage on letters carried by private ships (“vessels not employed as regular Packets”) until about mid to late April 1817.5 As per the Act, which is admittedly not well-drafted, such letters couldn’t be prepaid in India.6

Consequently, the London post office could charge sea postage again on delivery. In this case though, London seems to have allowed the sea postage prepayment in India7 and only marked inland postage due of 1s5d (distance from Deal to London to Inverness) plus ½d Scottish Additional Half Penny tax.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Max Smith and Martin Hosselmann for their inputs. To Terry Hare-Walker for sharing the image of the cover illustrated, which I first saw in a Zoom presentation he gave in October 2020 on ‘Madras Presidency Internal Mail before 1838’. Feedback and suggestions are welcome; please send them to my email address: abbh [at] hotmail.com.

References

Deshmukh, Cynthia. “The Rise and Decline of the Bombay Ship-Building Industry.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 47 no. 1 (1986): 543-547

Eibl-Kaye, Geoffrey. “The India Mails 1814 to 1819 (Part I). Negotiations between the Post Office and the East India Company.” The London Philatelist 113 whole no. 1314 (April 2004):78-93

Farrington, Anthony. Catalogue of East India Company Ships’ Journals and Logs 1600-1834. London: The British Library, 1999

Giles, Hammond. “The “King’s Post”, 1815-1819.” India Post 12 no. 1 whole no. 55 (January-March 1978): 15-18

Giles, D. Hammond. Catalogue of the Handstruck Postage Stamps of India. London: Christie’s Robson Lowe, 1989

Hackman, Rowan. Ships of the East India Company. Gravesend, Kent: World Ship Society, 2001

Phipps, John. A Collection of Papers, relative to Ship Building in India […]. Calcutta: The Author, 1840

Robertson, Alan W. A History of the Ship Letters of the British Isles (An Encyclopaedia of Maritime Postal History). III vols. Pinner: The Author, 1955-1964

Smith, Max, and Robert Johnson. Express Mail, After Packets, and Late Fees in India Before 1870. Wheathampstead, Herts, UK: Stuart Rossiter Trust, 2007

Tabeart, Colin. Robertson Revisited: A Study of the Maritime Postal Markings of the British Isles Based on the Work of Alan W Robertson. Limassol, Cyprus: James Bendon Ltd., 1997

Calcutta’s heydays in shipbuilding was in the period 1781-1821. In those four decades, some 272 ships measuring 122,713 tons were built in the various shipyards on the Hooghly of which 85% were built between 1801-1821 (Phipps 1840, p. xii-xiii). A terminal decline began thereafter both in Calcutta and Bombay; however, the Bombay shipyards did build some iron and steam vessels between 1829 and 1857 including the famous Hugh Lindsay. Much of the decimation of the Indian ship building industry can be attributed to British policies aimed at supporting their own shipping industry (Deshmukh 1986, p. 544-547).

Albion’s builder measurement (bm) was reckoned at 790 tons as per Phipps (1840, p.117) and 817.80/94 tons as per Hackman (2001, p.249).

After Packets were made at the post office as early as the 1780s. For example, a report in the Calcutta Gazette of 17 January 1788 states: “We understand the packet of the Thetis was closed on Tuesday last, and that an after packet will be dispatched this day; after receiving which on board, she will immediately proceed on her voyage for England.” Unfortunately, early post office regulations governing them have not yet been seen; the earliest which (implicitly) talks about the After Packet rate is from 30 October 1822 (Smith and Johnson, p. 110). However, letters dating to September 1816 exist with a manuscript ‘5’ on them probably denoting the After Packet rate i.e. inland postage of 5a from Calcutta to Kedgeree on single letters weighing one sicca.

Farrington (1999, p. 11-13) records four ships named Albion which made voyages from GB to India between 1762 and 1826.

A postal notice issued by the Madras GPO on 15 April 1817 said that as per orders from the London GPO dated 28 October 1816, letters by private ships would have to be sent unpaid thence. A similar notice from the Calcutta GPO has not been found but would have surely been issued and dated sometime in April 1817. Meanwhile, the Bombay authorities had read the 1815 Act correctly from the very beginning and wouldn’t accept prepayment on private ship letters (Giles 1978).

Clause XVI of the Act said: “And be it further enacted, That for the Port and Conveyance of all and every the Letters and Packets that shall be carried or conveyed by Vessels not employed as Packets from The Cape of Good Hope, The Mauritius and The East Indies, to Great Britain, there shall be charged and payable a Sea Postage of Eight pence for each Single Letter, and so in Proportion for Packets.” On the other hand, clause XLV stated: “…and that the Rates of Postage for the Conveyance of Letters from any Port or Place in The East Indies to Great Britain shall be received at the Option of the Parties sending the same, or upon their Delivery in Great Britain or Ireland, by the Deputies of the Postmaster General in India upon forwarding the same.” So the former implies that postage on ship letters will be charged in GB while the latter makes it optional.

In fact, evidence from existing letters show that London frequently (always?) allowed the prepayment made in India and didn’t charge the recipient again.