The Crusading Ribeiro of Indian Philatelist

India's first philatelic journal and its mercurial editor

This article was first published as "The Crusading Ribeiro of Indian Philatelist: Rival Indian Philatelists Step into the Ring." Philatelic Literature Review 71 no. 2 Whole no. 275 (Second Quarter 2022).

A short summary was published on the APS website on 5 July 2022: https://stamps.org/news/c/news/cat/library-resources/post/the-crusading-ribeiro-of-indian-philatelist

A slightly revised version appeared in Indian Philatelist - The Indian Philatelist: Philatelic Monthly Published in the Interest of Collectors and Dealers. Vol. I / 1894 - Vol. II / 1896. This is a reprint of the journal and is edited and published by Wolfgang Maassen (2025).

In the Western world, philately took a pivotal turn in the early 1860s when it moved from being the pastime of schoolboys and eccentric adults to a hobby of a more serious nature. The equivalent inflationary period for Indian philately came about some three decades later, in the 1890s. In a short matter of time, the tribe of collectors saw a rapid increase and some of the pioneering philatelists came together to form the earliest philatelic societies. Dealers proliferated and showcased their wares in the philatelic press; the more enterprising ones reached out to collectors directly through their regular price lists. The publishing and journalistic scene became vibrant, and the earliest philatelic books and magazines were issued.

In its earliest decades, Indian philately was pretty much centered around the great cities of Bombay and Calcutta. While Calcutta was the capital of British India, Bombay was fast progressing to become its economic hub (a title it holds to this day). Located on the western and eastern coasts respectively and separated by 1,200 miles of land, the two cities jostled on a lot of issues; those philatelic would not be left behind!

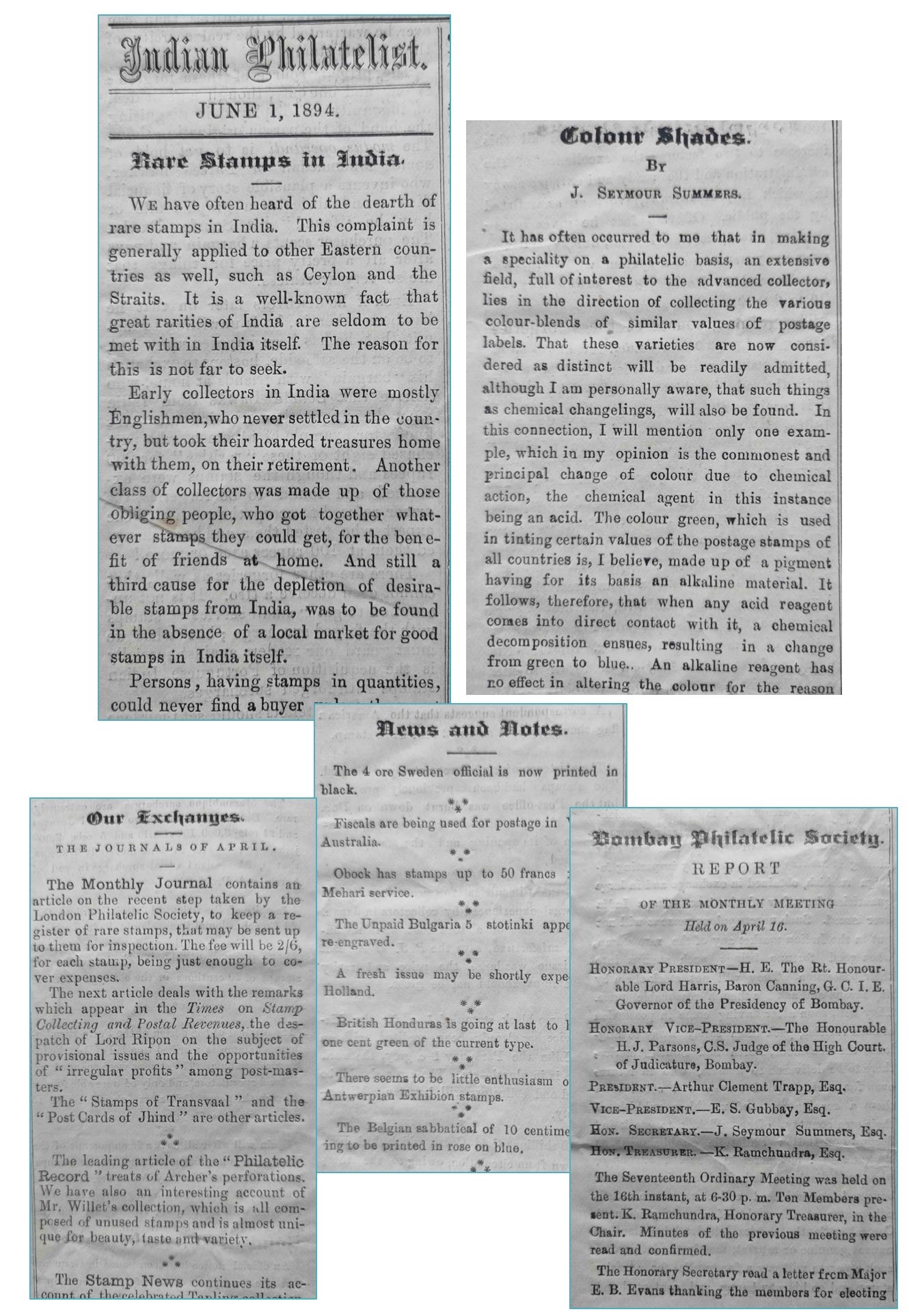

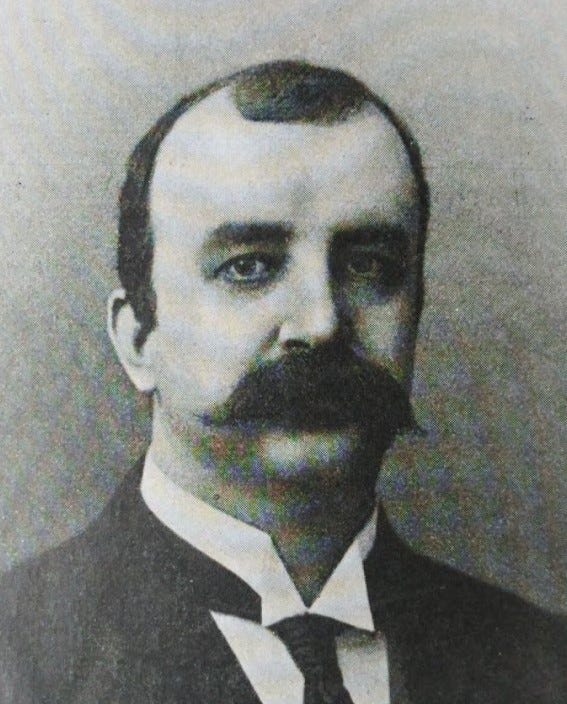

The accolade of being the first journal falls on the Bombay-based Indian Philatelist (IP).1 Given that Indian philately was dominated by the Britishers, it is a matter of surprise that IP was conceived, managed, and edited by a Catholic of Indo-Portuguese descent, Julio Ribeiro (Figure 1). Starting off in a small way, the journal peaked in its first year; unfortunately, it closed before it could reach the age of two. This was in keeping with philatelic magazines the world over; hundreds of journals sprouted only to die within a year or two, or after an issue or two. However, before it fizzled, enough paper had been set to type to give future historians more than a glimpse of the prevailing Indian philatelic scene.

Julio Ribeiro, IP editor

Unfortunately, we don’t know as much about IP’s first editor as we should. Born on February 16, 1867, Ribeiro received a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1888 when he passed first class; he was awarded the Ellis Scholarship and the Duke of Edinburgh Fellowship.2 Subsequently he became the first Catholic to receive a Master of Arts degree from the University of Mumbai; something he must have been proud of, given that it suffixed his name on IP’s masthead. He was mainly a collector of and expert in the stamps of Portuguese India. He may have collected some other Indian states and British India as well.3 Apart from IP, he edited a Portuguese language magazine called Bulletim Indiano.

Was Ribeiro a dealer? It is quite likely than he was not.4 However, his brother, Hector Ribeiro, ran Bombay Philatelic Company,5 a stamp firm of some repute.

Initial Days of IP

The first number of IP (Figure 2) is dated May 1, 1894, and is an eight-page paper. The introductory editorial clarifies its raison d’etre:

We make no apology for the present paper. It may be that the philatelic brotherhood is not large in India, but it is a growing one. If only opportunities are given them, Indian philatelists will make their importance felt…

On what IP proposed to cover (Figure 3), it said:

Our beginnings are necessarily small. We shall have usually an original article of philatelic interest, a chronicle of new issues, a brief review of important articles from the philatelic press of the world and short, scrappy notes and views.

(In short, the format of IP was quite similar to that of leading British and American magazines of the time.)

From a commercial perspective, it appealed to advertisers saying they now had a chance to buy space in a philatelic journal rather than take “recourse to lay papers, in search for a chance philatelist, among a crowd of readers who care not a jot for the wares one advertises.”6

Finally, the masthead of the paper read, “Philatelic Monthly published in the interest of Collectors and Dealers” and “Conducted by Julio Ribeiro, M.A.’ However, there is no address mentioned, which is strange. In the second issue, the address for communications is mentioned: ‘Dadar, Bombay, India.’ Dadar is a fairly large area in Central Bombay and, at the time, was far (some seven miles) from the philatelic hub in the Fort area of South Bombay.

The adjoined Table 1 gives a short bibliography of IP. Note that advertisement pages are in parentheses. From Vol. 1 No. 6, ad pages began to be numbered with Roman numerals.

Reception

The first issue of IP seems to have been well received. In its second issue, Ribeiro sounded excited:

The eagerness with which the “Indian Philatelist” was received by the public and their generous support has proved a great source of encouragement to us. Improvements can still take place and will be introduced gradually. The pre¬sent number has been increased to 16 pages.

(Ribeiro’s “16 pages” was 12 pages of reading matter and four pages of advertisements).

The international press, from America to England to Australia, were generous as well. The Philatelic Record, perhaps the best journal of that time, reviewed IP in its August 1894 issue:

We have now received the third number of the Indian Philatelist, and we cannot but congratulate the Editor and the contributors to its pages on the matter that has every month been provided for its readers.

The Philatelic Review of Reviews (presented gratis to all readers of the Philatelic Journal of Great Britain) of June 11, 1894, was of the opinion:

We cannot find a more exact address for our new and promising contemporary. The post-mark on the wrapper is Dadar. The first number appeared in May and contains eight pages of reading matter. The paper on which it is printed leaves some-thing to be desired, but we cannot expect everything all at once…

Advertisers in IP

One way to judge the quality and popularity of a magazine or newspaper is to browse through its advertisements; sellers do not put in their money in dud publications. In that, IP seems to have done something right since it managed to attract advertisements from India and abroad (Figure 4).

Some of the names seen are, from England: Stanley Gibbons, Ltd., Theodor Buhl & Co., Butler Bros. of Oxford, Alfred Smith & Son of Bath, and Thos. Rodpath & Co. From America: C.H. Mekeel Stamp & Publishing Co., R. F. Albrecht & Co., and Scott Stamp & Coin Co., Ltd. And from Europe: A. Weisz of Budapest and Roland Meister from Germany.

Apart from quarter to full page ads, there were classifieds as well. Of course, Ribeiro’s brother’s Bombay Philatelic Company and the editor’s own Bombay Stamp Exchange had a place in every issue.

As can be seen from the table, the number of pages of advertisements reached its peak towards the end of the first year before declining precipitously in the second, reflecting falling standards of the magazine itself.

Spat with Philatelic World

Depending on one’s perspective, Ribeiro comes across as either principled or rebellious. To a philatelic historian though, the fact that the pages of the country’s first magazine can be so interesting and entertaining is a matter of delight.

The first evidence that Ribeiro wielded a sharp pen comes from a column that he publishes under the pseudonym ‘Wenzel’ in the fourth issue, August 1894. We do not know who Wenzel was; perhaps the nom de plume of Ribeiro himself.

Wenzel made his first appearance in the second issue of June 1894 (Figure 5) wherein he congratulated the editor (!) for having the courage and fortitude in venturing upon such an undertaking. He went on to bemoan the state of Indian philately while pouring scorn on local dealers. In the fifth issue of September 1894, he cast a favorable light on the Bombay Philatelic Society (BPS) and its workings. He wrote a few more columns but none as scathing as the August one.

What ruffled Wenzel’s feathers was a not-so-flattering review of IP (Figure 6) in the July 1894 issue of India’s second journal The Philatelic World (PW). While the first 13 issues of PW were published by the young Calcutta dealer, B. Gordon Jones (Figure 7), he edited the first two only. Jones may seem harsh on a fledgling contemporary but his comments on its language and grammar are spot on.

Obviously, the rebel was not going to take this affront lying down. Wenzel charged Jones of being upset that a Bombay upstart had beaten his endeavor by two months. He inquired:

Surely there is room in the country for two such publications and if such be the case, it is but right to inquire why should the new born infant be gifted with such a short temper? What fairy god-mother presided at its birth?

Raising the Bombay-Calcutta rivalry card, he railed against what he felt was Jones’ rabidity towards his city’s philatelic scene:

There is no doubt that the Bengalee7 Philatelic Philosopher will find that he cannot enlist either the indulgence of an enlightened public or their support, if his publication is to be devoted to attacks on persons who are considerably known in philatelic circles on this side of India.

He then personally attacked Jones, the dealer, saying:

It does not require a very strong sight or a powerful magnifying glass to discern what this pretender is aiming at. Compare his offers for July, 1894, as given in the inside of the back cover and note the great rarities of India this well-stocked “Know-all, has for disposal.” (sic; the quotes are placed incorrectly). With one exception, there is hardly any rare stamp of India catalogued therein.

Reacting to criticism about its language, Wenzel defended the editor and criticized Jones:

Is he possessed of a certain amount of courtesy as due from one editor to another, when both elect to espouse the same cause and work for it. Is he so perfect in everything apportioning to philately and the English language thrown in, so as to pose as an infallible grammarian? Is he aware of the existence of such a person as represented by a printer’s devil?

(Unfortunately, the printer’s devil continued to plague IP in the future.)

Finally, against the insinuation that Bombay was the hub of forgers, Wenzel retorted:

By the by, does it not strike you that the shoe has pinched? Let the world-wise authority take a ramble through Lall and Bow Bazaar, and the labyrinths of lanes off Bentinck Street and go and satisfy himself of the respectability, scrupulousness and knowledge of stamps of the many so called dealers and then speak of Bombay as the lurking place of such. Alas! that a man should live in a glass house and attempt to throw stones!

Ribeiro/Wenzel obviously took one review too much to heart. We see this trait in him, again and again, that when he is pushed, he reacts with great hostility and does not mind making it personal.

The editorial of PW passed to C.F. Larmour (Figure 8) from the September 1894 issue. This seems to have placated Ribeiro/Wenzel. In IP’s November 1894 issue, Wenzel praised Larmour as a person with “intimate knowledge of stamps” and waved the white flag:

We are very pleased to note the change effected in the editorial chair of our Calcutta contemporary and regret that inadvertently we have been lead [sic] to do an injustice to a gentleman for whom we entertain a great respect and high esteem. Also that owing to circumstances, over which we have no control, the short comings of one person should have been visited upon another.

N.H. Mama, dealer and forger

Ribeiro’s adversary was the Parsee8 dealer, N. H. Mama who, Ribeiro consistently claimed in IP, was a forger. There may have been other reasons for the unpleasantness between them.

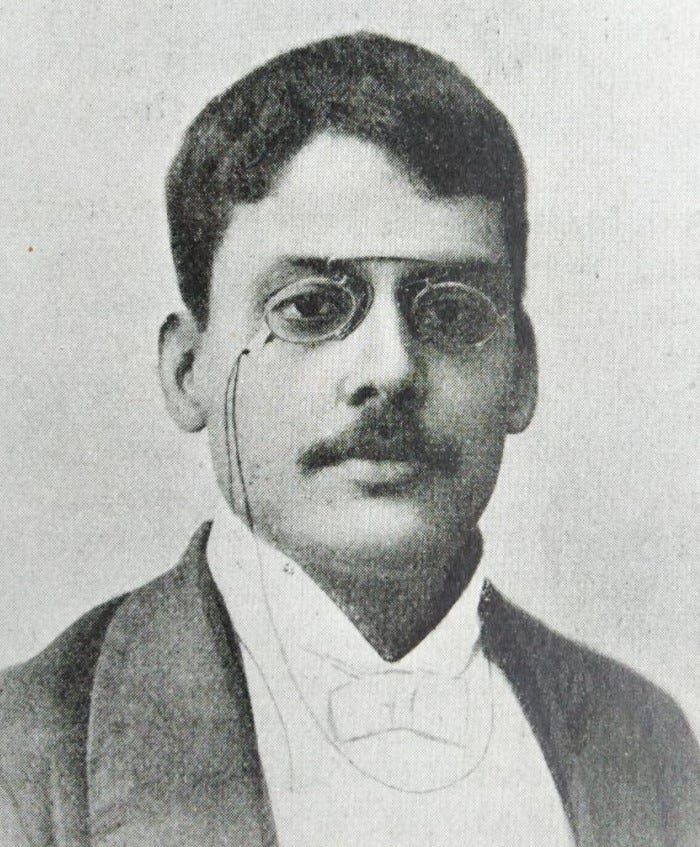

BPS (Figure 9) was formed when seven gentleman (and one visitor) met at the Presidency Surgeon’s office at Bombay on August 29, 1892. One of the founding seven was Julio Ribeiro. He was appointed the vice president at this meeting. However, he objected to the office bearers being appointed permanently, and said that it would be better to have the office bearers as they now stood only as a temporary measure till the next ordinary meeting. His objections, very likely, came from Mr. N.H. Mama being appointed the treasurer.

In its first ordinary meeting on October 3, 1892, voting for office bearers for the ensuing year took place; neither Ribeiro nor Mama were elected for a post, though Ribeiro made it onto the committee. In retrospect, Ribeiro sacrificed the post of vice president but managed to keep Mama away from the important post of treasurer. Unfortunately, as he would soon learn, Ribeiro could not keep a check on Mama’s influence on the society.

In a special meeting of the committee of BPS held a few days later on October 10, 1892, Ribeiro drew the committee’s attention to an article in The Philatelic Journal of America dated September 1892 about Afghan forgeries and Mama. Another meeting was quickly called nine days later, and Mama given a chance to respond. The sub-committee was convinced by Mama’s explanations that the forgeries were top grade and that he should not be blamed if he could not detect them before offering them for sale.

This must have surely disappointed Ribeiro.

Two years later, however, Ribeiro had the power of the pen. In the second issue of IP, in the column on forged Scinde Dawks,9 he said, “The primary source of these forgeries is one and one only…”

In his third issue, in a column aptly named “Black List”, Ribeiro came out in the open:

It may be to the interest of uor (sic) readers to learn that Mr. N. H. Mama, who flooded the market with a special issue of Cabul10 stamps, has entered his schedule in the Insolvency Court. During the transition period, he is trading under the name and style of the Great Philatelic Co. Those who were promised a refund for the Cabul forgeries and other bogus stamps will probably get nothing, as the stock of stamps which he represented as his assets realized only about ten rupees at Auction.

Stanley Gibbons Monthly Journal of August 31, 1894, reproduced this and confirmed Ribeiro’s assertion:

We can fully bear out the statement that this man has been selling forgeries, as we quite recently examined a collection of nearly 9000 stamps, formed by a gentleman residing in Persia; we picked out several score of Afghan, Jhind, Gwalior, and other stamps as bad, all of which had come from Mama.

September 1894 saw the start of a new magazine from Bombay called Indian Postage Stamp News (IPSN) (Figure 10). While the publisher/editor was shown to be one P. A. Sakloth, Ribeiro claimed in the November issue of IP that Mama was behind it. Apparently, Mama got into publishing to defend himself against attacks from the likes of Ribeiro and to promote himself.11 Ribeiro warned his readers,

We would like to know the genuiness [sic] of the advertisements and interviews, before advising intending subscribers to place their subscriptions.

Over the years, Ribeiro seemed to get the impression that the BPS would not do anything to curb Mama, his activities, and his influence on the society and its members. Things came to a head in the first few months of 1895.

Spat with Bombay Philatelic Society

While Ribeiro surely had an allergy for Mama, his relationship with BPS in general seemed to be cordial until 1895. In the first issue of IP of May 1894, Ribeiro reproduced a paper on ‘Unpaid Postal Impressions of Mauritius’, read before BPS by its secretary, J. Seymour Summers. The following issue carried a report of the 17th ordinary meeting of BPS. The report is interesting in that Ribeiro mentions the start of IP and that he would be willing to give a copy of the journal free to each member of the society and also carry the reports of the society free, provided the society reduced the annual membership fees from 12 rupees to 5 rupees.

One possible reason for Ribeiro’s request may have been his desire for more members to join the society but it was idiosyncratic to link the two. Nevertheless, the “question was postponed for final settlement to the next meeting, when it was hoped Mr. Ribeiro would be present and would urge good reasons in support of his proposition.” In the next meeting Ribeiro seemed to have backtracked and proposed that as soon as the society’s membership reached 30, the fees should be cut in half to 6 rupees.

Following a successful philatelic exhibition of The Philatelic Society of Bengal, BPS decided to hold one as well. The first signs of a true rift were now visible as Ribeiro complained in the February 1, 1895, issue, “It is sure to be a failure, as few of the members of the Bombay Philatelic Society have been invited to in send their exhibits and only two days were allowed, in which to prepare them.”

In the April 1895 issue, reporting on the exhibition, the knives were truly out.

Our local society is a curious anomaly. Avowedly started for the benefit of philately, it has done nothing to develop the science in the course of its three years’ existence. First, dealers were admitted and Mr. N.H. Mama was the treasurer. Then they were excluded and some of the bad cargo had to go.12 An exchange branch was started, which converted every member into an authorized vendor of stamps – until that absurdity was also knocked on the head. Then came projects innumerable – a reference list of Portuguese India, a philatelic exhibition of rarities, an auction sale, a Magazine and so on, until these perpetual projectors ware shamed into action and under the able direction of the Treasurer matured a hastily adopted scheme. Its practical results are transmitted to posterity in a pamphlet, which is destined to cover the Society with anything but glory. We had some difficulty in securing this monument of philatelic knowledge of the managing committee of the Bombay Philatelic Society. The Secretary seemed to know very little about it. At last a copy was got from the Treasurer and it was a revelation.

Dr. C. F. Paco’s ‘unchronicled’ rarities of Portuguese India figure on the opening pages of this marvellous work. This ‘specialist’ seems to have a curious idea about the meaning of ‘unchronicled’ rarities. Mr. A. J. Agabeg has gone one better than his colleague, the Doctor. He exhibits a lot of stamps from a dealer’s stock and the selection has been made without any discernment. A member of the Committee might have known better. Another exhibitor has follow¬ed in the steps of this gentleman, but not to that extent.

As a whole, the show was very poor and though the non-collecting public may have concurred in the extraordinary ideas entertained by some of the exhibitors regarding the value of their exhibits, philatelists must have formed a juster (sic) estimate of the whole affair….all the members of the Society who care for its good name and still hope to convert it into an instrument of usefulness must regret the hole-and-corner arrangement, which resulted in this exhibition of ignorance and incompetence. Aping is not imitating.

In a column in the May 1895 issue titled, “The Bombay Society Again”, Ribeiro writes:

How not to do it, will fairly characterize the actions of the local Philatelic Society. The latest move of the Committee is the resuscitation of the exchange rules and the exchange section. In this model exchange society, if a member wants to exchange his duplicates, he cannot do it. He must either buy or sell them. The restrictions on the pricing of stamps are simply childish.13 The whole manoeuvre [sic] will merely benefit the few shady dealers, who are in friendly terms with the Committee and who cannot sell their goods in a legitimate way. The so-called exchange rules were expunged for a good cause14…The philatelic experts will of course have an opportunity of sanctioning the genuineness of spurious stamps, and the members will continue to sell their bad duplicates, under the thin guise of exchanging them.

It is obvious that Ribeiro is throwing everything at Mama. In the June 1895 issue, Ribeiro sounds anguished, part of which betrays his helplessness.

It is significant that the Bombay Philatelic Society has found a champion of its doings in the person of Mr. N.H. Mama, the gentleman whose connection with forged Scinde Daks and bogus Cubuls is well-known. It is well-known that Mr. Mama is the sole owner of the Great Philatelic Co., and it is painful to see members of the local Society parading themselves in the company of such dead beats.

What (or Who) is “Truth”?

To needle BPS, the May 1895 issue (the first issue of Volume II), reproduces a report carried by PW in its April issue on the Bombay exhibition. Of course, PW did not have much good to say about the exhibition, hoping that “India’s premier (sarcasm!) Philatelic Society will do itself more justice in its next exhibition.”

Ribeiro must have felt vindicated by this review. Nothing else explains why extracts from a rival would find a place in his journal.

Ribeiro is not yet finished with his crusades. In the June 1895 issue, a letter from ‘Truth’ was published (Figure 11); like ‘Wenzel’, this was probably another pseudonym used by Ribeiro to give the impression that there are others out there who shared his distaste of the way BPS was functioning.

Truth commended the editor for the stand taken against BPS. He then went on to criticize the society’s “Philatelic Golden Gang, whose objects are to give a name and a standing to people who would otherwise find no status in the philatelic world.” He regretted that BPS failed to respond to the criticism of the exhibition and laid the charge that most of its members are dealers. He claimed that “member after member has left the Society in sheer disgust at the pretense of work.” Finally, Truth alluded to the good name that BPS had in English philatelic circles (through the writings of Marcellus P. Castle15 and Stanley Gibbons16) when he concluded:

It is doing a public service after this to divulge these facts, that respectable members may choose better associates and that outsiders may know exactly the credit that ought to be attached to the reports of great progress which are exported to Europe, simply because they find no credit here.

The Court Martial

BPS was quick to strike back. At its general meeting held on August 8, 1895, a resolution was unanimously passed requesting the council to take notice of the Truth article (BPS seemed to be aware that it was no letter but rather an article written by the editor) which made “some very injurious imputations” against BPS. Just two days later, the council met and decided that Ribeiro, as editor, must be held responsible for articles appearing in IP and that he be called up, as member of BPS, to explain. It further said that a meeting of the council would be held on August 19, at which the question of permitting Ribeiro to remain a member of the Society would be considered.

In a letter dated August 10, the Hon. Secretary, Summers, informed Ribeiro of the charges and asked him to either respond to them before the 19th or appear before the council on that day. On August 15, Ribeiro wrote back saying that as a member of the society, he was not in any way responsible to the society for anything that may appear in IP. Dripping in sarcasm, he said, “I cannot extend my congratulations to the form of notice that the Council of the Society have resolved to take of the matter.” He further asked,

You speak of a charge, but you do not define it… Your Council evidently are going to constitute themselves into a tribunal for the purpose of judging me. It is very kind of them to do so, but I must decline to be a party to such a ridiculous assumption or to any travesty of justice.

Interestingly, Ribeiro signed this letter as “Founding Member, Bombay Philatelic Society,” perhaps trying to remind the society of his long-standing relationship with it.

Perhaps wanting a compromise, the council gave Ribeiro another chance to answer the charge and postponed the matter to August 27. Ribeiro declined to play ball again. The whole sordid drama came to an end when the council decided to strike his name off the roll of members with effect from August 28.

The whole saga of BPS, Ribeiro, Mama, and others make it apparent that no one party can claim to be the arbiter of truth. BPS comes out as bereft of good strong leadership; consider the numerous times its rules were changed in response to lobbying from one quarter or other. Further, in supporting Mama, a notorious forger, certain council members of BPS were certainly in the wrong.

And despite his protestation to the contrary, Ribeiro does not come out smelling good either. One can charge him for vitriolic personal attacks when criticized, for indulging in settling petty scores rather than trying to carry people along, for rebellion when not called for – in short for being quite immature and negative in his approach and for having a perennial chip on his shoulder.

Final Days of IP

Ribeiro does not mention the society in IP again. Meanwhile, its last few issues see a sharp fall in standards. Ribeiro seems to have expended his energies in his numerous quarrels and no longer seems to have the enthusiasm required to run the journal; it has been pretty much a solo effort.

Apart from reprints from contemporaries and advertisements, IP no longer had much to offer. The April 1896 issue was the last to come out; there is no indication in that issue that the journal was shutting down for good.

Larmour, then editor of PW, announced in the October 16, 1896, issue:

We regret to learn that our Bombay Contemporary, the Indian Philatelist, has collapsed.

Another reason for the journal shutting down may have to do with Ribeiro’s own life drawing to a close. He died on February 23, 1897, aged just a week over 30. In the February 16, 1897, issue of PW,17 Wilmot Corfield (Figure 12), the editor, paid his tributes:

I am deeply grieved to hear of the death, in Bombay, of Mr. Julio Ribeiro, who was the editor of the Indian Philatelist. He was a keen Philatelist, and a clever writer. This sad news came to me just as I was closing these notes.

Postscript: Bombay’s philatelic decline

With Mama’s Indian Postage Stamp News having shut down with the last issue coming out in September 1895, BPS decided to start a magazine of its own titled The Quarterly Philatelic Circular (QC) (Figure 13) under the editorship of its Hon. Secretary, Summers. The editorial of the first issue, January 1896, spoke of the need for an official organ of the Society and to “chronicle the excellet (sic; the editorial devils troubling IP hits the new magazine!) services which it has, during its brief but useful career, rendered to philatelic science.” It hit out against existing publications which were “too much under the conduct of persons who, either professedly or indirectly, deal in stamps.” Unfortunately, the pages of QC show that it had a pretty uneventful and unexciting 1896 and it folded after four issues.

The year 1896 saw the BPS in terminal decline. Bombay lost its status as the philatelic capital of Indian philately to Calcutta, its great rival, where exciting stuff was taking place. Early 1897 brought the birth of The Philatelic Society of India and its brilliant journal, The Philatelic Journal of India. The next quarter century belonged to Calcutta until a new breed of Bombay philatelists appeared in the 1920s who revived the city’s glorious days.

Indian Philatelist became The Indian Philatelist from Vol. II No. 1 issue of May 25, 1895.

The Times of India. “University Intelligence: The Second B.A. Examination.” December 21, 1888: 5.

A report of the meeting of the Bombay Philatelic Society held on July 23, 1894, says that Ribeiro showed several forgeries of the small service India, surcharged Gwaliors, and a pair of unused India 1854 four anna stamp.

The pages of IP carry the regular advertisements of one Bombay Stamp Exchange. While the word ‘Exchange’ in the title of Bombay Stamp Exchange hits at a more innocuous activity, the entity’s advertisements in IP make it clear that it was indeed a dealer in stamps of India and its native states as well as that of the whole world. (The bibliophile may be happy to note that the Bombay Stamp Exchange sold philatelic books, catalogues, and albums as well!). Now this entity’s address is always shown as just ‘Dadar’. This area of Bombay, far from the philatelic scene, is the same one as that where IP is published from. It is hence reasonable to suspect that Riberio may, in fact, have been its owner. However, we need to consider two aspects: (a) dealers were not allowed to be members of the Bombay Philatelic Society and that some had resigned when this rule came about; Riberio did not (b) when Ribeiro’s relationship with the city’s philatelic establishment was nose-diving and he was under much scrutiny, no such charge was laid at his door by the other side.

The Bombay Philatelic Company was founded in 1889 and celebrated its centenary in 1989. The Indian operations looks to have now closed. In 1947, its proprietor, Mr. J. F. Droucette Dias, left India to go to the UK and shortly thereafter emigrated to the US; his brother took over the Bombay business. Dias’ son, Brian Dias, runs Bombay Philatelic, Inc. from New Jersey and deals in new issues. See bombaystamps.com.

As quoted in the IP. The first and last two to four pages of each issue were advertisements. The cost of advertising was the following: For a single insertion, one page Rupees (Rs) 12, half a page Rs. 7, quarter page Rs. 5, and one-eight of a page Rs. 3-8. The currency was 16 annas = 1 Rupee. Rs. 3-8 was therefore 3 rupees and 8 annas.

Bengalee or Bengali i.e. someone of or from Bengal, the state in which Calcutta is located.

Parsee or Parsi is a member of a group of followers in India of the Iranian prophet Zoroaster (or Zarathustra). The Parsis, whose name means “Persians,” are descended from Persian Zoroastrians who emigrated to India in possibly the 8th century, to avoid religious persecution by Muslims. There are less than 60,000 Parsis in India today and most of them live in and around Bombay. Notwithstanding their small numbers, the community has always wielded a disproportionate economic influence.

Issued in 1852, the white, blue, and white Scinde Dawks (SG nos. S1, S2, and S3) were used only in the Scinde province of India.

That is, the stamps of Afghanistan.

Sample the editorial from the third issue of IPSN dated 25 November 1894. It lauds Mr. N.H. Mama “towards enlarging philately in India” and that “his disinterested devotion is sufficiently well known to call for any further eulogy and comment.” The previous issue cheekily asks who ‘Wenzel’ is. A few months later, during the Ribeiro-BPS spat, IPSN sides with the latter. Unfortunately for Indian philately, the magazine closes with Vol. II No. 1 of September 25, 1895 being its last issue.

In its fourth ordinary meeting on December 19, 1892, the Society decided that dealers should not be admitted as members. N. H. Mama and N. D. Bottiwalla, a respected Bombay dealer, resigned shortly thereafter.

The exchange rules passed in the April 6, 1895, committee meeting of the Society were: (a) Cash be paid for stamps at the time of their removal from sheets (b) 5 percent of the price be credited to the Society’s funds, (c) Basis of exchange shall be Stanley Gibbons’ latest catalog, and (d) Mr. Alex. J. Agabeg be appointed the Exchange Secretary.

Ribeiro had proposed the cancellation of the then-existing exchange rules of the society. The motion was passed in the October 24, 1894, regular monthly meeting (twenty-sixth) of BPS.

In the winter of 1892/93, Castle took a tour of the East. He visited Bombay and met members of BPS on December 8, 1892. He was mighty impressed and wrote in The London Philatelist of January 1893 that BPS was flourishing and judging by the interest taken therein by its members, he anticipated a promising future.

Gibbons visited Bombay in March 1893 and was, like M. P. Castle, highly taken in by a city “teeming with philatelists, stamp collectors, and stamp dealers.” Recording his experiences in the April 29, 1893, issue of Stanley Gibbons Stamp Monthly, he declared that Bombay took first rank in India as the chief (philatelic) city, although Calcutta was nominally the capital. He also attended a meeting of BPS on March 20 and wrote that BPS appeared be prospering exceedingly, and doing much good to the general body of collectors resident in the city.

While Ribeiro died on February 23, the news was carried in the February 16 issue of The Philatelic World. This may be because this issue, Vol. III No. 7 & 8 Whole No. 31, came out later then the 16th. It was already made into a double number and in the editorial, Corfield says, “We are late this month, but we trust, better late than never.”

So much info on early Indian Philately trade and societies....well documented.

Thanks for this Abhishek ji