The Bibliophile of Vancouver and Sarasota: William Hagan

Philatelic Literature storyteller and collector and writer

This article was first published as “The Bibliophile of Vancouver and Sarasota: William Hagan” Philatelic Literature Review 70 no. 4 (Fourth Quarter 2021).

“Perhaps you can forward the below email to Abhishek Bhuwalka as I can’t make his email work.”

So read the first words that I ever received from William Hagan.

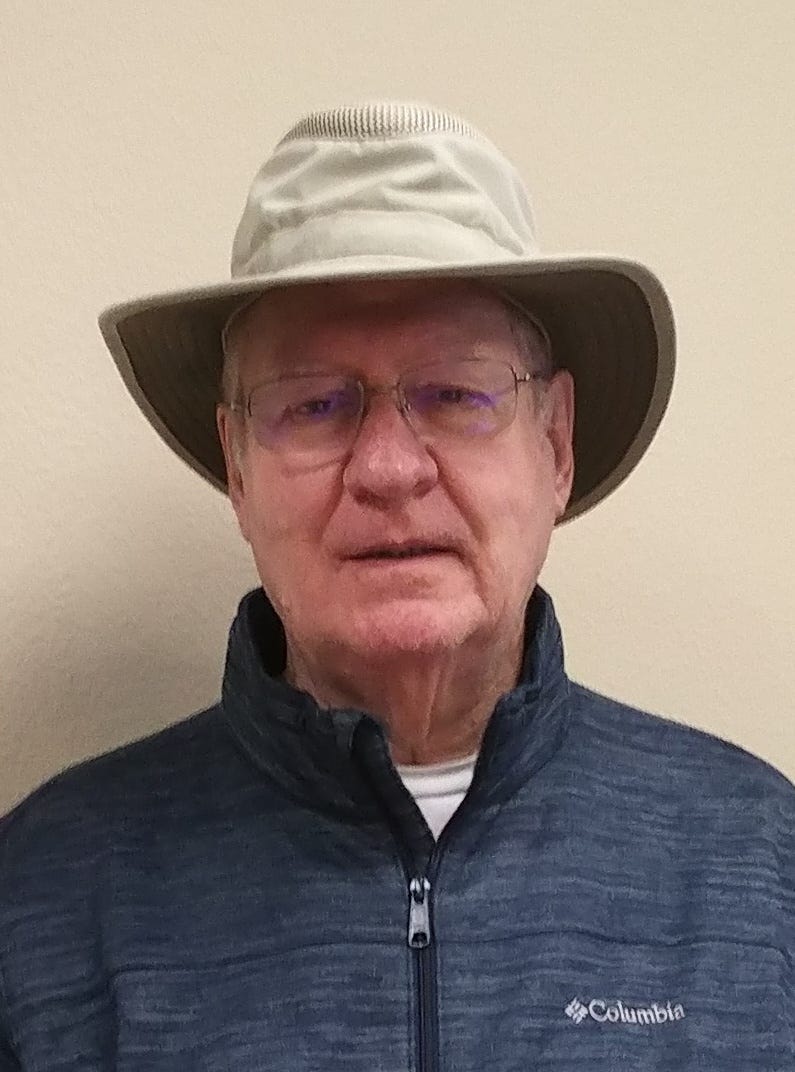

In June 2018, in response to my article on Harry Hayes and the index to his auctions, Hagan (Figure 1) wrote me an email with his thoughts; it was forwarded to me by the editorial staff of the Philatelic Literature Review (PLR). Since then, we have corresponded many times; mostly he starts with offering his congratulations on my latest article or interview, and then goes on with elucidating on philatelic literature as well recollecting adventures from his collecting days. Hagan is a storehouse of philatelic anecdotes, most of which cannot be published!

Hagan has been away from philatelic literature for some time now. If one considers that his library was sold in 2000, it has been two decades; if one regards that he stopped collected literature in 1987-88, in the aftermath of a personal tragedy, it has been more than three. But as a similar saying goes, “You cannot take philately and philatelic literature out of the man (or woman)!” While some of his recollections are, understandably, foggy, Hagan’s love and appreciation for the hobby in general and for books in particular is unmistakably strong. His unorthodox thoughts on what constitutes philatelic literature, his forceful insistence on its importance, and his revealing some unusual places where it can be found are essential reading for every collector of stamps and/or postal history.

My first article in the PLR of Q3 2017 was about filling in Hagan’s description of the various editions of Alexander J. Sefi’s masterwork An Introduction to Advanced Philately from 36 years earlier. Further, the “eureka” for my recent interviews published in this journal came from Hagan’s similar work in the 1970s and 80s. Hence, I owe some part of my philatelic journalism to Hagan and my sincere thanks go out to him.

Hello Bill. I am so glad that I am interviewing you in the philatelic bibliophile series. It has been years, almost two decades, since the philatelic community has heard from you. What have you been doing in this time?

Traveling (Figure 2). We traveled for an entire year in 2002, and for four years straight between 2007 and 2010. We have also made many shorter trips. We have seen the world, often home staying. Other times we have stayed in apartments living in the community. Shopping where they shop, eating where they eat, living where they live, having library cards, going to wedding receptions, attending various religious ceremonies, and so on. We have spent five months in Paris, three months in London and Rome, and one month in virtually every major city in Europe. Also, three months in Turkey and Australia, two months in New Zealand, and six months in various Asian cities. And three months in your wonderful country of India, including one month in your wonderful city of Mumbai. We had a one-hour train ride into the once-named Victoria Train Station1 in Mumbai, hanging out the car doors for comfort! Some trips required starting toward the door two stops before your destination or you would never crowd your way out before the train left.

For all our travels on trains and buses, and in all our apartments and home stays, we never saw another American. They travel in American groups, stay in American hotels, eat where Americans eat, and spend a few hours seeing various sights before going on to the next stop. We would meet them at various sights and they were always amazed that four hours wasn't enough to see a major city like Paris.

Starting from the very beginning, please tell me about yourself.

My full name is William John Hagan and I was born in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan on November 3, 1940. This makes me a ‘Uper’ (or Yooper). You have great status among locals if you are one. But if you move there even at one day old, you can never be Uper! At six months my family moved to East Lansing where I grew up across the street from Michigan State University. I finished high school, spent three years in the Army, and returned to Michigan State where I received a BA and a masters in Instructional Media.

My work life involved publications and style guide management, advertising, consulting, and proposal writing until I retired early. My wife, Dorothy, has a PhD in Human Nutrition. She has held a number of important positions in business and academia.

How did you get interested in philately and philatelic literature? Did you have a stamp collection as a kid or later?

My love for libraries started when I was just a kid. I used to read entire sections. Later I learned book binding as a hobby. I would bind all sorts of theses, periodicals and older volumes earning one hour of free use and materials for my own library. I began to see that there were different editions, learnt what constitutes a complete volume or periodical year, saw the enormous range of many academic subjects, and so on. I was later able to transfer my interest in books to philatelic literature.

Between 1949 and 1952, I pedaled papers for four years making the princely sum of $23 a week (I saved enough to pay for my college education by the time I was 12). One day on my route, I saw a collector mounting the U.S. 1932 presidential series. I always remember that single incident. However, I didn't start collecting until I reached my early thirties.

My original interest was in the U.S., but I talked my wife into collecting. Each auction we went to, she spent our entire budget on Australian stamps! So, I switched to them. The Australian catalogs were basic in the early 1970s.2 I started to search for more definitive references, and I guess that's how my interest in philatelic literature began.

We still have the Australian collection. It's not much but has some interesting airmail covers. Perhaps I will get around to appraising the collection one day.

In response to editor Charles J. Peterson’s request in the Philatelic Literature Review’s Q4 1975 issue for contribution to a new column on philatelic literature price trends, you stepped up to the plate. Why? Had you done any philatelic journalism before then?

As best I can remember, the idea for the "Prices Realized" column came from a reader. I don’t remember why I decided to answer Peterson's editorial. I had a few articles in Linn's, and that's it.

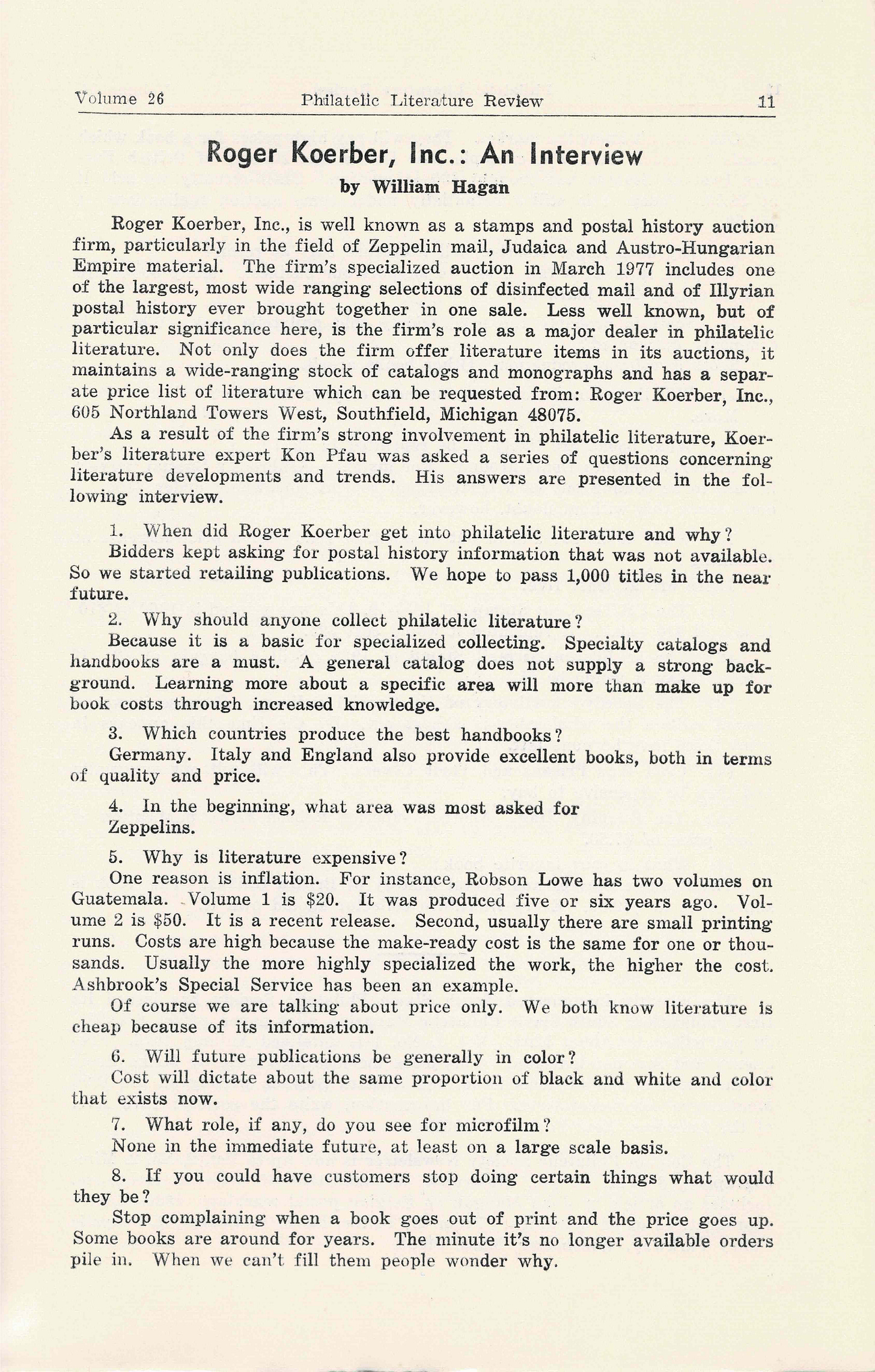

Your column, “Philatelic Literature Price Trends” (Figure 3), saw the light of day in the PLR’s Q3 1976 issue and continued for more than a decade until Q1 1987. It was unusual when an issue did not contain your name. Tell us some of your thoughts about writing that column?

My work schedule then was demanding, and required a great deal of mental effort. That left me tired and with little time. I had to “panic out” many columns.

The hardest part writing the column was getting auction catalogs and prices realized, if any. Most literature dealers have microscopic margins selling literature, so the cost of mailing a catalog to a writer was something they were loath to do. At one time Harry Hayes stopped sending me catalogs as I was not a paid subscriber. He relented, however, when I notified him that I could not afford to pay for the many auctions that I covered else I would have to stop the column. Hayes was good about this; many foreign dealers were not.

How did you manage to make a supposedly dull subject into something so engaging and entertaining?

I am often the "life-of-the-party," knowing endless stories to entertain others. I used this character trait to transfer these tales into my columns. One problem with this practice was the enormous mistake I made, in one column, where I erroneously claimed a lot of literature lots didn't sell when it did. I received a stiff letter from the dealer. I apologized in a following column although the dealer changed their PR a few auctions later to eliminate the mistake I made. Though the editor wrote saying he should have caught it, I always regretted that. I tried to be especially vigilant in future columns.

I also think that the “predictive text” on prices brought about reader interest as much as the subject itself. Some literature, like some stamps, either commonly appears or does not appear for twenty years. It’s something of a gamble to let desirable material pass by. Most advise “BUY IT.” And I did this as well, although if a flood of the items subsequently appeared, the original buyer would have paid too much.

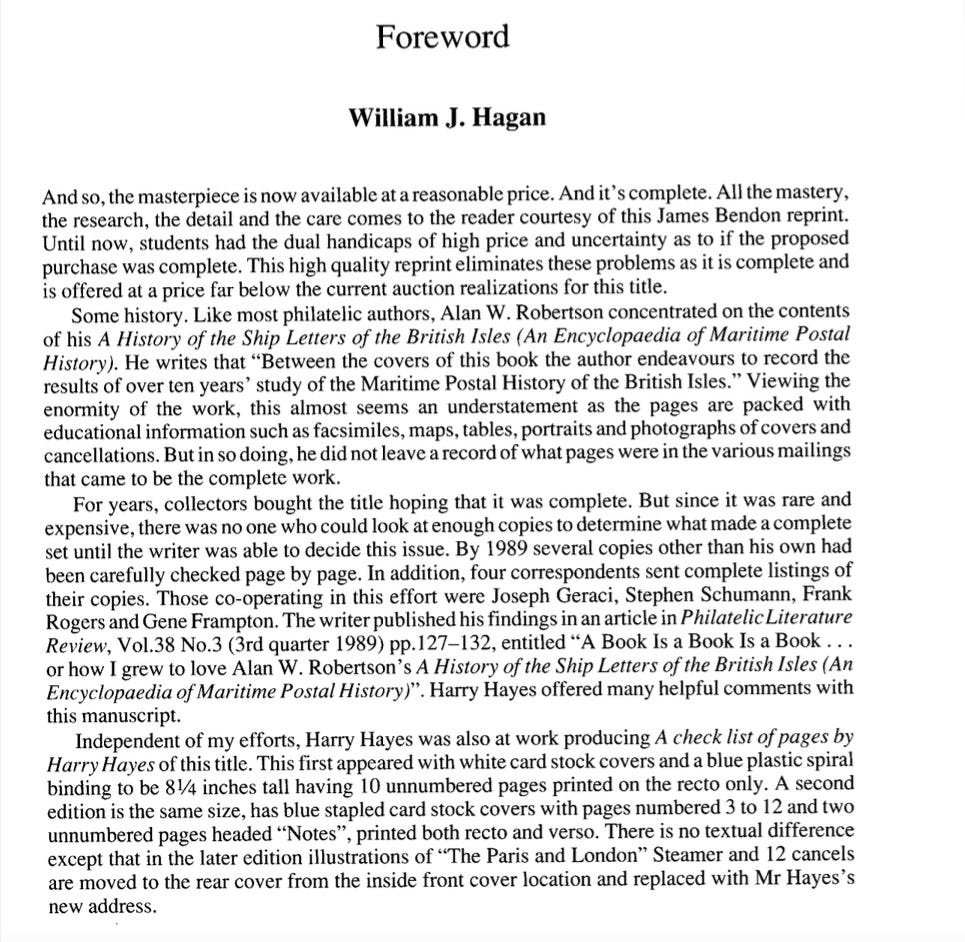

Apart from the price trends column, you also used to interview (Figure 4) notable personalities in the PLR. I confess that your interviews inspired me to start my own series a few years back. How did you hit upon this idea?

Every passionate collector has strong opinions about what a journal should contain. I did too. I think most notable personalities jumped at the opportunity to put in "their two cents."

When you were regular in your writings, two of the very best – Charles Peterson and Bill Welch – were the PLR’s editors. Share some of your experiences with working with them.

Writers should be so lucky to have an editor like Bill Welch. He offered suggestions, corrected some of my spellings, and was just the kind of cheerleader a busy person as myself needed. I had little contact with Peterson though. Both editors were busy professionals and I appreciated that they, for the most part, printed what I wrote.

You have some strong thoughts on the importance of philatelic literature. Please elucidate.

I often heard people say the only thing they are interested in literature is the information. Nothing could be more wrong.

Examine any area of philately and you'll find a 100% correlation between the strength of the area and the literature about it. A strong society journal, specialized group(s), dealers, periodicals, auctions, and state and local group publications will see that area thrive. Take away most or all of these and the area dies.

Literature goes a long way toward determining how someone collects. Walk into a collector’s home and see 10 or 15 large albums and a few monthly periodicals and catalogs, and I can assure you that their material will see an auction description as follows: "Accumulation of 10 or 15 albums with so many stamps (125,000, for example), make offer."

Many collectors think a current stamp catalog and a popular journal is all they need to form a scholarly collection. It will never happen. Instead, you will get a "space filler" collection not unlike every other collection in the area. They are surprised when their "collection" is of no interest. And, why should it be? Virtually every day a collector shows up at a dealer with the same kind of collection. Endless low values, inexpensively produced covers, and several volumes. Evaluating these collections takes about 30 seconds. Paging through the first few pages, you know what the rest of the album will be. The collector is astonished. They, or their surviving spouse, have been told it’s worth thousands. They leave confused and angry. You don’t need to ask how large their philatelic library was. You know.

On the other hand, see a home with a few albums, but a wide range of handbooks, periodicals, memberships of specialized societies (one knowledgeable collector used to say, "I make money with every handbook, journal, and specialized society I belong to"), correspondence (letter files are another vastly important reference not often offered; if you have a chance to buy one, do it), perhaps color, perforation, and cancel studies, and there will be value. Often, this latter collection will far exceed the "accumulation." I have been president of a large, strong local, a statewide, and an international philatelic society (West Suburban Stamp Club, The Oregon Stamp Society, and Society of Australasian Specialists or Oceania). Without exception, the finest collections and the most informed collectors had the largest and widest philatelic libraries. So philatelic literature often determines a collection's value.

Philatelic literature teaches geography and history. You learn the world as it existed, changed and exists today.

Philatelic literature stimulates the imagination, broadens your intellect and gives you a never-ending treasure of knowledge.

Philatelic literature gives you goal(s) which are ever-moving to your delight. Start down one avenue and find ten others open. Look in those and each offers another selection.

Philatelic literature offers companionship. You marry it and it becomes an inspiration for your life, making days more worthwhile.

Philatelic literature assures you of a longer and healthier life. Ask any health professional and they will tell you intellectually active people live longer, healthier lives.

Philatelic literature forms life-long friendships. A fraternity forms with you and others who have your passion. I think this is one of most satisfying aspects when I was active.

Don't reduce philatelic literature to "it's information only." It offers you the world and unlimited options. Take advantage of them.

You also have an interesting take on what constitutes “philatelic literature” and some unusual places to hunt for those. Please elaborate on this.

In the early 1900s the English book dealers gave up trying to define what a book was! Have you ever seen a good description of what constitutes philatelic literature? It’s really undefinable. I remember one philatelist talking to me, saying he and a second person were thinking of doing a bibliography of philatelic literature. I responded that it would take 100 full-time editors working 100 years to cover the subject in its broadest definition, whatever that is. Of course, it would be very dated when finished!

First, at an international or national show, read the large gold/gold exhibits and you'll note almost all consist of original research. There is no handbook or periodical article alone that has the same research. Often these exhibits, combined with other similar material, will become name sales. Many bemoan that these exhibits are "check book philately." There is some merit to this, as "completeness" is a major consideration in awarding medals. The last few items are often beyond most collectors' means. But I've seen local shows where an inexpensive stamp is shown as a single, plate block, sheet, color study, errors, and endless covers with postal rates. These are wonderful studies that cost little. Hence, exhibits are surely philatelic literature.

One day, go to the post office headquarters in Washington, D.C., and take one elevator to floor 10 and then a second one to floor 11 where the Postmasters General’s library is. The library is good sized and is one-half case laws as regards the post office. Years ago, there were over 10,000 technical reports on all aspects of stamp production. These have restricted access and I am not sure if anyone has ever looked at them. Think of the answers on paper, glue, perforations, etc. that could be answered. Certainly, this last is highly relevant to any literature listing, but I don't think either have ever been listed. Do they go back to 1900, or before? I don't know. I never had time to investigate. One of its patrons, however, was Henry Beecher. Readers of The American Philatelist from time ago will recall his postal history letters to the editor. I helped empty his apartment of philatelic material and another scholar used it plus his own knowledge to produce postal rate books.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, The New York Public Library received 2,300 foreign journals (if I remember correctly) not received by the Library of Congress. I once spent three weeks there and I produced a 1,000-page bibliography of their philatelic holdings (of which I printed a few copies). At that time, they had two 800-volume-printed bibliographies in the reading room which stopped several years (I remember 1971) before the date I was there. Many cards listed a foreign publication, such as Brazil post office annual reports, and gave a start date. Information about the run was held in another enormous card catalog back somewhere. You had to hire an accredited researcher at $30 an hour to go back and give you details as to how many there were. The same was true for periodicals. I don't think the material has ever been completely described. Certainly, foreign post office annual reports and journal runs would be philatelic literature.

The U.S. Civil War has seen millions of titles. One common area is journals and letters written by thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands, of soldiers. Many contain references to some mail topic such as mail routes. Is this philatelic literature?

I was at the Truman President Library and learned they burned the envelopes that held correspondence. I tried to get them to save these for a postal historian to examine. I doubt any presidential library saves envelopes. Certainly, they would at least have had information on the postmaster general in that administration. Is this philatelic literature?

Think of all the government publications of all the governments in existence since … (pick a date). Would you include stampless covers or early postal routes before there were post offices? Is cuneiform postal communication?

Near Philadelphia is an enormous estate with a 10-story building with priceless early Americana. They have a library with a large post card collection. I once saw one in D.C. with some 30,000 postcards of U.S. Post Office buildings. Is this literature?

There are countless histories of U.S. and foreign military units, often held by the units themselves. There is postal information in most of them. More philatelic literature?

Every state has a state historical society. How many have philatelic information?

There are some 3,000 counties in the U.S. Some of their governments, as Chicago, are in large buildings. They surely have postal information. Others are in a single room with none.

You have written about the whole “complete” business in the past.3 Why don’t you tell us more about this?

This comes back to people buying literature for the information. But what information are they buying?

Fournier's material was bought by, I think, the British Dealers Association.4 Perhaps they bought the Sperati forgeries, but the buyer is unimportant. What matters is that each forged stamp existed in different quantities and sometimes in sheets. When the albums were made up, the lowest number got one of every example. Soon, however, the number of complete examples began to diminish. To my knowledge there is no existing record of which book got what. In an attempt to remedy this situation, George Van den Berg, who dealt as Lowell Ragatz, bought over 15 copies, taking out those issues missing from his master set. Did he eventually have one of every example? I doubt anyone knows. He published a green bound softcover book of his master copy.5 If you are going to buy a Fournier you must have this master copy to see just how complete your proposed copy is!

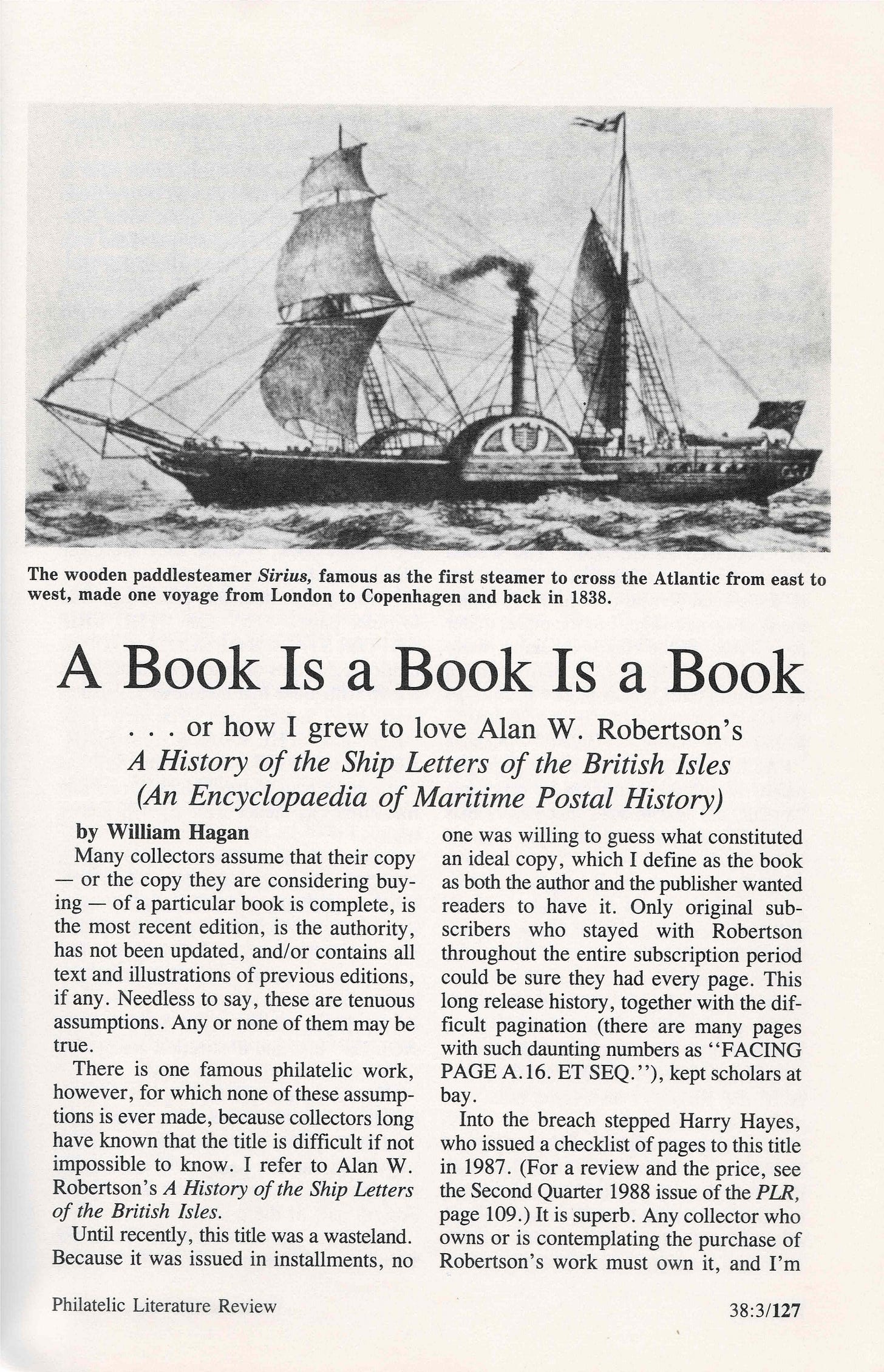

Another example is Robertson’s Maritime Postal History of the British Isles (Figure 5).6 Robertson sent the book out in a series of supplements. You had to subscribe over a period, which was of considerable length. Many let their subscriptions lapse. But not only did you have to get all the mailings, you had to get all the additions. These came in the form of mysterious page numbers. For example, you have the initial page number B.48 with the heading “Early Ships of the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company.” When Robertson had to share more information, he sent across a page numbered B.48/A (and B.48/B on its rear); this had to be inserted after page B.48 and before B.49. Then B.48/C and B.48/D and B.48E and B.48.F. Not to mention B.48/B1 (and B.48/B2), which had to be inserted facing B.48/B! His numbering was bewildering and a mystery to most. Now you buy the work. What did you buy? There is a book, put out by (as I recall) a Malta dealer7 that reproduces the complete book. I know this as I wrote the foreword (Figure 6). Unless you have the reproduced complete book, you don't know whether your copy, and hence the information you have, is complete or not.8

Periodicals are notorious for missing or misnumbering their issues. What constitutes a complete run? Many have supplements, indexes, and what not. How about the Prince Edward Island plates in volume 2 of The London Philatelist?9 As I remember there are six. Are they in the "complete" group that you bought?

In the early 1990s, after you had stopped your price trends column, you wrote a few articles especially on your road trips to various libraries such as the Library of Congress, the New York Public Library, and the library of the Collectors Club. You have already answered the “why.” Now to the “what?” What did you learn there?

Apart from the libraries you mention, I have been to countless postal museums, libraries, and historical societies along with the U.S. Archives. I have also spent time at the Chicago Public Library doing research on the postal articles in The Chicago Defender. Other visits have included the library in the U.S. Post Office and parts of the Smithsonian before much of its material was moved to the now-National Postal Museum. I have been to places such as the Dupont Home, going through their post card collection. Abroad, I have visited countless foreign libraries including the British Library and have seen a large number of national postal exhibits. I have loved every minute of these visits.

First, everything may not be on the computer. Many researchers take for granted that the computer lists everything. Often not true. For instance, The Free Library of Philadelphia Library put their philatelic books on a computer. Administration demanded entries end at a certain date. I was there and a librarian showed the various philatelic literature cards that she wasn’t able to enter.10

Further, some holdings never get listed. The Library of Congress received thousands of Spanish plays for safekeeping during the Spanish revolution. A friend knew they were still sitting in the boxes untouched. This was decades ago so maybe they are now included in some listing, returned, or still sitting there.

Finally, and unfortunately, going to major library almost always means you must go to a metropolitan area. And, you must stay there to accomplish anything. That can get expensive.

What are your thoughts on libraries?

Many modern librarians are dispirited by the loss of the book to the electronic age. Many libraries are little more than a number of terminals for users to use Google or some other database. Of course, the reference librarian is hardly used, or may not exist, as "everything" is on the net. This is a gross error, as a librarian, familiar with that part of the library, can tell you what's there and what's not. Especially in the U.S. Archives or the Library of Congress, finding the right librarian can save countless hours. The Archives will "pull" and have on a cart the material you ask for on the day you arrive. The Library of Congress used to let researchers have a wire cage in the stacks where they could have a coffee maker, computer, desk, light and carts for weeks, or even months, I suppose.

Hopefully this virus disaster will end one day. When it does, going to any library, such as the APRL, should be scheduled months in advance. Don't just show up. Librarians have meetings, vacations, and a workload. Also be specific. I collect a certain stamp, area, postal history subject and want information in this area. Can I examine the forgery collection in my area of interest? Can I make copies? Photographs? What would you suggest I examine in my subject area? I can say that every librarian I have ever dealt with has knocked themselves out to be helpful.

Following from an earlier question, a lot of archival material of past greats are in philatelic libraries. You mentioned to me once that you saw Stanley Ashbrook’s files at The Philatelic Foundation in New York City. Could you elaborate more on this?

Private correspondence among philatelists represents perhaps the greatest source of information that’s ignored. Ashbrook,11 who was the early U.S. material expert, bowed to no one but Carroll Chase, another expert in U.S. classics. Ashbrook kept scrapbooks about two feet by 18 inches. On each page he taped his letter and then taped the replies slightly offset under his letter. Many of the letters contained inflammatory remarks which would produce a legal action today. I volunteered to photograph each page and publish it. The caveat was that I could not afford to stay in the city and needed to take them home. “No” was the answer. There were some 40 books which I assume are still there. Some Ashbrook questions would probably be answered if this material became available.12

You mentioned to me once that whenever you would write to George Turner (Figure 7)13 mentioning that you had seen a rare item, Turner would reply saying it was not rare at all; the reason being that Turner would have tens, sometimes hundreds of that item! What relationship did you have with Turner?

A short story first. Decades ago, we were in D.C. for a week, tried to get a hold of Turner and failed. A few days later, (I don't remember the circumstances anymore), we moved. Turner called every hotel and hospital in D.C. looking for me so he could show me his library. But I had seen it. His home was only a short distance from The Library of Congress. One day I went from there to his house, a long narrow structure, and got a tour.

Like virtually all literature collectors but Stanley Bierman and some others, Turner wrote little about literature. He would often write to me heaping criticisms on my column. I remember one particular letter where he claimed a book that I said was rare was common. He had 150 copies or some such number. Well, that's why it was rare! I never wrote back saying, "George, it's a rare book because you have 80 or 90 percent of the printed copies.” He would purchase unsold stocks and they would sit. One such book he sold me from around 1915, at the very inexpensive publication price, was noted as remainder stock.

Turner also belonged to an enormous number of philatelic societies. He had boxes of journals from small societies still in their shipping containers. He spent decades promoting his library as the world's best. When Koerber bought the remainder14 and put it up for auction, it was already well known.

You co-wrote the George T. Turner Philatelic Library (1981) auction catalog along with Don Pfau.15 Did the auctioneer, Roger Koerber,16 approach you? (Figures 8 and 9)

I don't remember how I became involved in the sale.17 I wrote the early material using the Crawford Catalog and other works such as The Journal of the Philatelic Literature Society.

Tell us more.

I lived an hour away and would take home boxes of material to lot in the evenings. Then I would also drive to Koerber's office on the weekends where Don and I worked long hours.

Turner's Library was packed into boxes in no apparent order. You would find a run of journals from, say, Vols. 7 to 11. Was there Vols. 1-6 and or Vols. 11 onwards in other boxes? Sometimes there was and other times not. This meant that each lot of journals would take a long time to describe. For instance, The Turner Sale had The Metropolitan Philatelist as lot 1151. It was a large format paper that must have had hundreds of issues in boxes that stood over six feet high! A describer, doing research as I did for this sale, might get 40 lots done in a day. Maybe! To count and try to confirm if all the numbers were there for this periodical would have consumed a day, or more! No dealer can afford to put such a lot in his catalog. You might use the words "believed complete,” which I should have done here. This lot did $575 plus a fortune to ship.

There was tremendous pressure exerted by Koerber to end lotting and put the sale on, as money was short. He approached me once and said something to the effect of, “You must make Don end this lotting as he can’t do it himself.” But Don was determined to make this a great sale and ignored this pressure for several weeks. Finally, Roger simply put a date by which all lotting was to be done. That meant that a lot of the material remained unlotted, perhaps 150 large boxes.

Turner once bragged that he belonged to something like over 300 societies, specialty groups, and the like.18 There were boxes with their mailings, most issues unopened, divided by cardboard. I have always wondered what treasures these would have held had we the time to open and go through these mailings? It was not to be.

You have an interesting story about your purchase of the Fournier album. Please share.

Roger paid me “so much per hour” in credit for the sale. For this service I was given a $5,000 credit (as I recall). I expected to buy several nice handbooks and the lot of The Philatelic Journal of India.

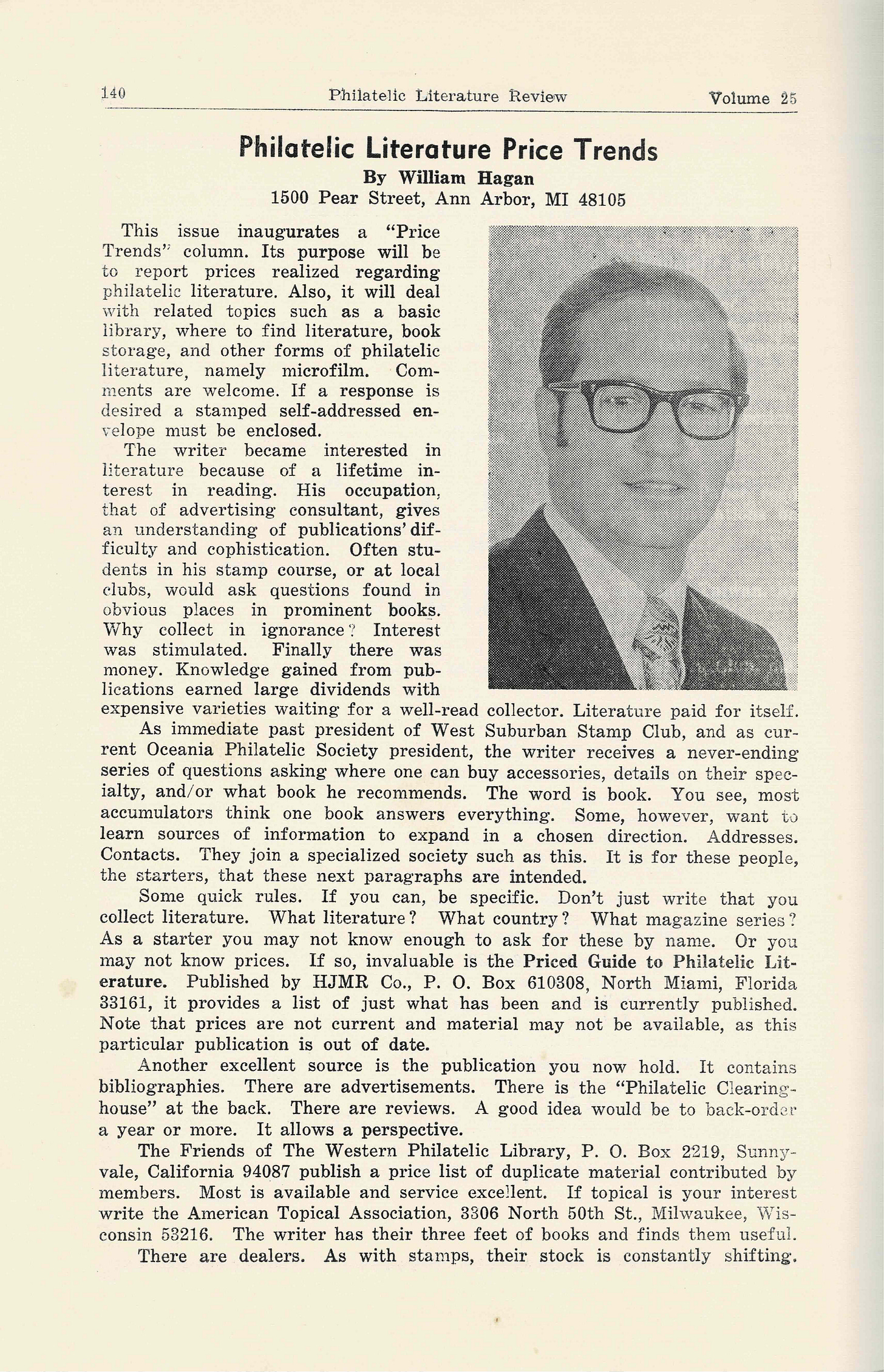

But the spirited bidding stunned everyone. Turner's decades-long self-promotion had brought out bidders as never before. The room had 30 individuals, some being agents representing many clients (Figure 10). Prices reached stratospheric heights over and over. Each session lasted hours longer than expected. I remember one dealer (also an auction agent), Louis K. Robbins, had several bids. After the floor would stop, he would announce his second highest bid which was much higher than even that on the floor. The Turner sale was a revolution. I can confidently state no sale before or after has been even a shadow of this auction.19

Now back to the Fournier.20 I bid and bid and lost and lost! Like everyone else in the room, I could not believe these high prices would continue, but they did. The Fournier was one of the last lots that I was interested in; I had to buy it or lose the $5,000 credit that I had. So, when it came up as lot 3044, I bought it for $6,000. It was a bad buy since the Swiss and other key material was missing. I knew this. If I had been able to forecast the record prices for everything, I might have simply paid the high price for some of the earlier lots.

The Philatelic Journal of India (PJI) lot was a couple of identical runs of the first 12 years. I love that journal but I may be biased. Hence, I was happy to learn that you too have had a very high opinion of it. Why? Further there was a bidding war for it in the Turner sale, wasn’t there? Estimated at $450, the lot realized $2,100.

I think it’s the rarest and best early journal, surpassing even The London Philatelist in quality. The Crawford has it starting at about the same time as the latter.21 Searching all my previous literature sale catalogs I couldn't find a single long run of the journal.

The Turner Sale had the early volumes. There was a “buy bid” on this from India. Lou Robbins wanted the lot and kept bidding. Finally, he said, “Do you have a buy bid?” Well, you aren’t supposed to let anyone know who and what a bid is and so Roger was stuck. Standing in the back of the room I signaled what to me was outrageous bid of $2,000! Lou promptly bid $2,100 and lot 1290 sold at one advance of my bid.

Why did it sell for that? If you were the buyer, it’s possible that articles from the early period may have had information priceless to your collecting interest. Or when something rare comes up that you need, you have to pay the price or maybe never see the material again.

Apart from the Turner sale, did you write the descriptions of any other auction catalogs?

I co-wrote the descriptions in the Herbert J. Bloch Philatelic Library which was auctioned by Koerber in 1985. Unlike the Turner sale, this one didn’t contain material from other vendors. I also did some lotting of Roger's very large library, which was sold by Charles Firby in 1988; but his widow wouldn’t let me take lots home and so my involvement was limited.

Apart from Koerber and Turner, you would have interacted with many colorful and not-so-colorful characters in philately. The 1980s was a really buzzing time, a golden period for philatelic literature, was it not? Could you relate some anecdotes from this period?

You find some collectors whose collection fills the house. I was in one such giant house where the couple lived in a six-by-twelve-foot basement concrete room. The rest of the house was inaccessible! It was owned by Richard Cabeen.22 He had been a stamp columnist appearing in a Chicago newspaper. The house and its contents were left to the Collectors Club of Chicago. The couple had passed several years before and club members still had not been able to get into some parts of the house!

Many will mistake a person's appearance as a sign of their wealth. Wrong! I visited a Collector's Club (in Dallas if I remember right) and was invited to a member's home. It was a modest, maybe 1,200 square-foot, structure. Entering the living room, the TV antenna consisted of two wires hammered into the ceiling. I didn't expect much. For hours this person brought out rare Hawaiian material and Oklahoma Territorial Covers, and showed me handbooks showing the largest example of a rare U.S. stamp. Then he would open an album say, "here it is." He casually mentioned in passing that he could make at least $10,000,000 in one day from dealers who wanted parts of his material! This was probably 40 years ago.

I taught a class in stamp collecting for an adult education class just once. This single occasion brought many calls to appraise stamps. I remember one person particularly. She had over one hundred covers with clear cancellations from the late 1840s in Ann Arbor, Michigan. She cut out the stamps, leaving just a small paper margin. I wanted to weep.

Who are some of the dumbest buyers? People with high educational qualifications! Over and over, you see them spend enormous amounts on material that is junk. They think success and wealth in one area will translate into another. One MD came in with over 50 sets of C13-5, the "Zeps." Even the most cursory look at most auction catalogs will show them for sale, often in plate blocks, blocks, of single sets. Who wants 50 sets? No one! It would take years and years to sell them. Another doctor stopped at our house, proud to show at least 75 early and very expensive U.S. singles. They had pin holes, missing corners, hinge marks…in short, they were space fillers, perhaps worth five percent of catalog value. He had paid full catalog! He stormed out of the house after I suggested that he negotiate a significant reduction. Later I ran across his wife. She informed me he had bought a fortune in coils, all of which were misidentified, making them a fraction of what he had paid.

Unlike many collectors, you have a soft spot for dealers! Why?

Most collectors think they are more intelligent than dealers. Well, they aren't. Ignoring them because you don't want to pay them a small profit is a mistake. Get to know and trust reputable dealers and you will not regret it.

Few collectors will try to put themselves in a dealer's position. Offering your material for sale, if you do so, meets the hard world of a dealer's reality. I knew dealers who in those days wouldn’t lot a book (or stamp or cover) unless it would bring $50. This amount was needed to cover (catalog) printing and mailing costs. As also labor; to write a lot takes about as much time for a $5 item as for a $500 one. It’s no surprise that dealers want as many high-value lots as possible. No such lots and you get a "collection" description, if that, described elsewhere.

To put an economic goal on literature handbooks, especially rare handbooks, and some periodicals will be required to interest a dealer. A scholar's library, on the other hand, sees great value in lesser items, such as correspondence, supporting materials, clipping files, and even inexpensive literature. These will sell "in the context" of this large scholarly collection.

If I were a dictator, I would have large statues of some philatelic literature dealers put in front of the APRL!

A couple of years back when I sent you a draft of one of my articles on the Williams brothers’ Fundamentals of Philately and how it was never “completed” as it was intended to be, you turned the observation on its head by talking about contributors whose articles were never published because of long series.

Unnoticed, but fundamental, is the loss of contributors whose articles are "page-limited" out in a long series. The PLR, for example, produced several long bibliographies that eliminated any chance for other authors to publish. Existing authors simply give up. In short, there is a cost to producing a long work no matter what its value. Laudatory remarks drown out these thoughts.

In a perfect world there would be the resources to print all worthwhile articles.

You wrote to me once that you did not believe that it was so much the post office as it was the railroads that helped create the “American identity.” Why do you believe so?

It’s a myth, perpetuated especially by doctoral theses, that the post office created an American identity by making mail available to all parts of the United States. Baloney! Read the percentages of first-class mail for the 1800s and you see no year had over seven percent first class mail. In addition, few could read, and with high first-class rates, few used the post office. It was the railroad that played a major part in creating the identity. In fact, every small population wanted a railroad so it could expand. Try and find a reference where people were clamoring for a post office.

Up until RFD (rural free delivery), the railroad and the post office were almost the same. In short, and as noted by a Postmaster General, the post office was the railroad. Where it went the post office was added. It grew rarely anywhere by itself. Look at the late 1800s Post Office Annual Reports and they are about 80 percent railroad data.

Apart from the railroad and explorers, what made America’s expansion possible (the so-called "manifest destiny") were the wars in Europe. Remember that Napoleon kept Europe in turmoil from 1803 until 1815. France had a population of about 29 million which was many times that of other countries; so, he fielded an endless number of armies. He attacked virtually everyone in this period and kept them busy and away from America. Further he also sold Louisiana to the U.S. and considered it a steal.

Unfortunately, once myths are established, they are almost impossible to correct.

You mentioned to me that you used to work some 16 hours a day and hence you could manage to retire in your late 40s. Could you elaborate on that? How did you manage to find time to write your philatelic literature columns in this period?

For some time, I worked in any area that required 80 plus hours a week. There were 25-hour days, 39-hour weekends, months of 18-hour days all under immense pressure. Pay was substantial. I relocated to the west coast and did some consulting and a service manual. Our life, however, was rotten with racing around Saturday to shop, get dry cleaning, service the car, etc. We had no kids and had saved from when we got married so I just stopped working at 48. I’ve never regretted it.

You retired from work in 1988 and you had stopped writing your column the previous year. Was there any connection between the two?

It was the result of a personal tragedy. My mother died after a long horrible illness from brain cancer after two years. During that time, I lived in Michigan to help with her care while my wife lived in Oregon. We saw each other only once every two months or so. She had just started there and had no time off, while my busy work schedule kept me in Michigan. When I finally got to Oregon, I was psychologically exhausted to the point it took me a year to recover. And I found retirement gave me time to do all the things we had jammed into Saturday when we both worked.

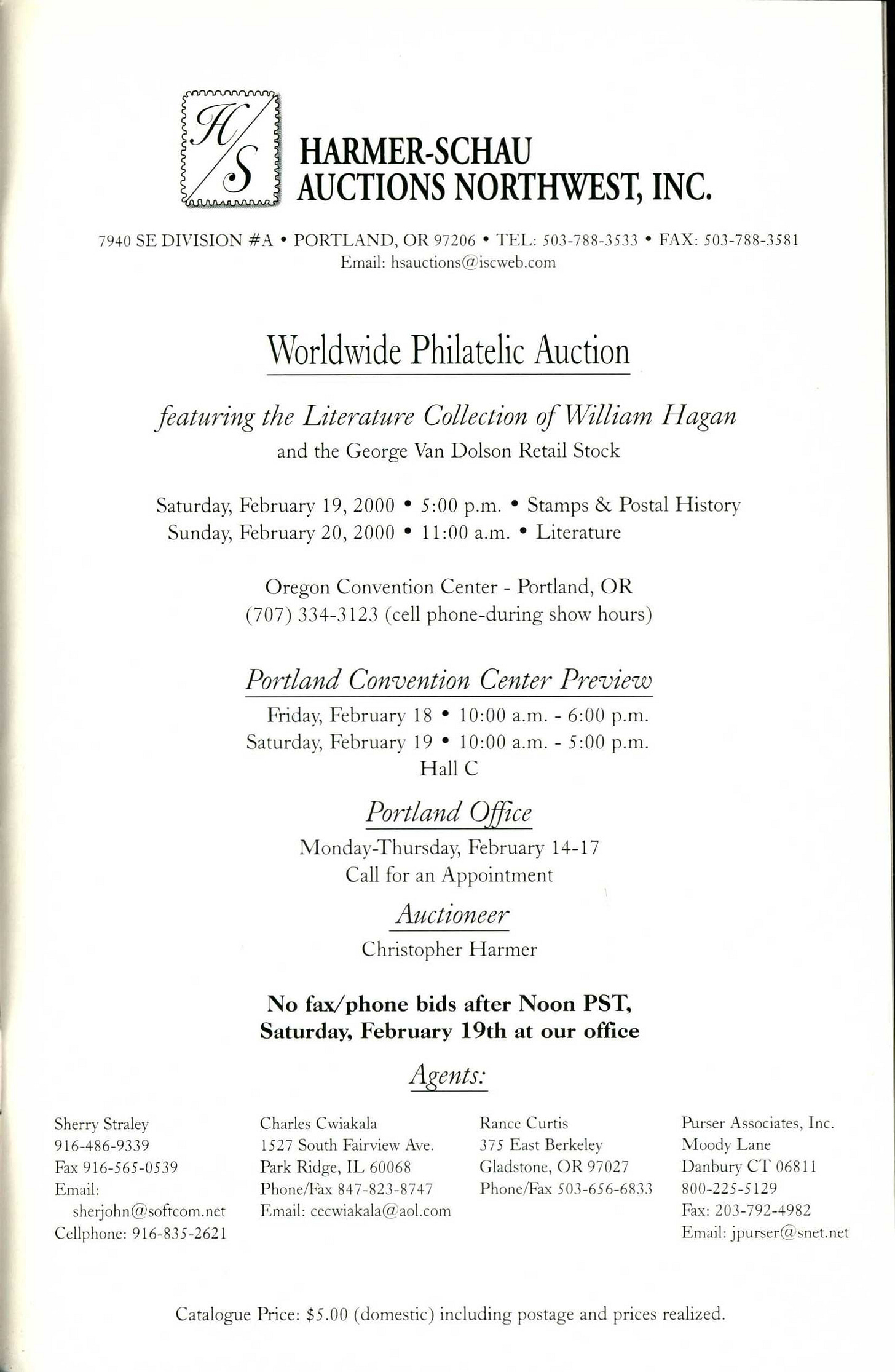

You told me that you sold your library in 2000.23 I had not known about it and nor have I seen the auction catalog. Could you give more details? Why did you sell them at a young (for philatelists) age of just 60 or so?

The APS had a show in Portland, Oregon, where I lived at the time. My library had tremendous bulk – it was in a room of 605 square feet – and I had wondered how I would get it to an auction house. The show was right across town so moving the material there was easy.

Bidding at the auction (Figure 11) was spotty, but then again, no literature auction, and few other auctions, would match the frenzy of the Turner Sale. Prices realized more than $51,000. I sold some items by private treaty; my best recollection is that the total eventually reached $65,000.

If you invest a large sum in any collectible, you hope to at least recoup your expenditures. I did this with my library, which sold for more than I spent by a considerable amount. Add the fun, education, and nice people I met, it was like playing rounds of golf, or any pleasurable activity, for free.

Which were some of your favorite literature titles?

While I sold my library, I kept one book and one catalog. The book was the "Crawford.” As a philatelic literature collector, I consider it the most scholarly single volume ever done. The catalog is of the 1981 Turner sale.

What about stamp boxes? Apart from philatelic literature, you used to collect those, right?

We have a modest collection of about 250 items. A few cost more than $1,000 and one cost several thousand. We went to Sacramento to a show and saw the American Philatelic Society collection. It was rather modest but it surprised me that they had even one.

The home of this area is England, where several collectors have over 2,000. We once attended a London Sotheby's auction that had four Faberge stamp boxes that sold for about $22,000 each some years ago. When these were offered, Sotheby employees materialized to man at least 10 phones. There were also enamel stamps on other stamp boxes. We were finishing a year of travel and simply didn't have the money to bid. I would think $250,000 would be a conservative estimate on the former and $125,000 on the latter should they come up for auction today.

The Queen of England has one in her Buckingham Palace Museum. It appeared to be made of a single agate stone that had been cut diagonally. It was rare material. It would be priceless if it ever came to market. (Figure 12)

The boxes are made of virtually any material you can think of. There have been some sales, but I haven't followed these for several years.

You live in Vancouver, Washington, during the summers and Sarasota, Florida, during the winters. Apart from the travel, how do you keep yourself occupied?

For the past many years, I’ve bought over 1,000 kids’ books at sales and garage sales and given them away free to churches, relatives, many youngsters, neighborhood kids, even some physical therapy workers where I have health care. Recently, I gave some books to a kid in the hospital elevator. I gave another large bunch to a preschool and sent nine large boxes to a Sarasota church. I’ve written over 1,000 letters to kids using Aesop Fables and other examples. I send haikus, various slogans, and real estate examples to kids whose parents are in that business and on and on. I make envelopes out of wall paper books and have over 300 different weight pens. Every paragraph is a different color. And, I use calligraphy on envelope covers.

Acknowledgments. Thanks are due to Bill Hagan for this interview despite not being in the best of health. Further, I would like to acknowledge Chris King RDP, Chairman of The Royal Philatelic Society’s Philatelic Collections Committee and Scott Tiffney, Librarian of the APRL for helping me with photographs. Any feedback or comments are welcome and may be sent to my email id abbh@hotmail.com.

Built between 1878 and 1887, Victoria Terminus is a historic train station and a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Mumbai. Initially named after Queen Victoria, it has been renamed as Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus.

Contrast to the situation currently, when Australia arguably produces the best stamp catalog series in the world - The Australian Commonwealth Specialists’ Catalogue - edited by Dr. Geoffrey Kellow RDP and published by Brusden-White Publishing of New South Wales.

Hagan, William. “Just What Do They Mean by ‘Complete’?” Philatelic Literature Review 38, no. 1, whole no. 142 (1st Quarter 1989): 9-11.

François Fournier (1846-1917) was a stamp forger based in Geneva. His stock of forgeries was bought by L’Union Philatélique de Genève (Philatelic Union of Geneva) who, in 1928, produced 480 albums containing his works.

Ragatz, Lowell. The Fournier Album of Philatelic Forgeries: A Photographic Composite for Reference Purposes (Worthington, Ohio: Janet van den Berg, 1970). Janet van den Berg was George’s wife.

See the most interesting article - Hagan, William. “A Book Is a Book Is a Book…or how I grew to love Alan W. Robertson’s A History of the Ship Letters of the British Isles (An Encyclopaedia of Maritime Postal History.” Philatelic Literature Review 38, no. 3, whole no. 144 (3rd Quarter 1989): 127-137.

James Bendon (1937- ) of Limassol, Cyprus, reprinted the complete work in 1993. This reprint was in two volumes and was 80% of the size of the original. Bendon is best known for his works on UPU specimen stamps and for publishing some important titles of philatelic literature between 1988-2006. He moved to London a few years back.

As Hagan mentions in his 1989 article referred to above, another way to check if a copy is complete or not is to refer to a checklist produced by Harry Hayes. See Hayes, Harry. A History of The Ship Letters of the British Isles (An Encyclopaedia of Maritime Postal History) by Alan W. Robertson: A Check List of Pages. (York: The Author, 1987).

These plates illustrate J. A. Tilleard’s article, Prince Edward Island Stamps, and were published in the January, March, and April 1893 issues of The London Philatelist.

In the early part of this millennium, Hagan supplied Brian Birch a photocopy of the catalog cards from the library relating to philatelic bibliography. They had not been included in the library’s computer owing to a shortage of time. Since they include many important and rare books, including numbered editions, Birch had the cards typed up and included in his The Philatelic Bibliophiles Companion.

Stanley B. Ashbrook (1882-1958) was one of the foremost experts of early U.S. stamps and postal history. Between 1951-57, he published his iconic – Special Service – which was published in parts for subscribers. See Hagan, William. “In Search of the Special Service,” Philatelic Literature Review 45, no. 4, whole no. 177 (4th Quarter 1997): 256-259 along with letters to editors that the article provoked in later issues. This work is now digitized and available on Richard Frajola’s website: rfrajola.com/AshbrookSS/ashbrook.htm.

After his death in 1958, Ashbrook’s archives were acquired by The Philatelic Foundation. In 2017, Ashbrook’s scrapbooks, slides, and index cards were digitized and made available by the Foundation on its website: philatelicfoundation.org. A news report appears here: linns.com/news/us-stamps-postal-history/2017/may/philatelic-foundation-serves-up-free-digitized-ashbrook-files.html.

George Townsend Turner, Jr. (1906-1979) was a multifaceted philatelic personality. One of philatelic literature’s greats, he was an expert in U.S. Internal Revenue stamps, very active in organized philately, curator of the National Stamp Collection, Smithsonian Institution 1958-62, and so on. At the time of his death, his library was the largest in private hands and had the most comprehensive collection of U.S. philatelic publications. His name has cropped up in my earlier interviews, especially the one with Leonard H. Hartmann published in the Q4 2020 issue of The Philatelic Literature Review.

Turner willed his library to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington but wanted them to take only books that they did not already have. So, they took his card file, over 3,000 books and related material, and 80 percent of the journals. These form the core of today’s Smithsonian National Postal Museum library. Roger Koerber is believed to have bought the remainder for some $45-50,000. This contained 12 tons of material and filled two trucks, each 22 feet each. Further, Turner gifted the American Philatelic Society his collection of its memorabilia and publications, spanning the entire history of the society. He gave Herbert A. Trenchard a quantity of auction catalogs, including every example in his library not already in Trenchard’s; in early 2021, Trenchard’s own collection of about 125,000 items was donated to the American Philatelic Research Library. See Trenchard, Herbert A. “The George T. Turner Philatelic Library.” Philatelic Literature Review 30, no. 3 (3rd Quarter 1981): 180-188 for more details.

Donald J. Pfau (1945-1985) worked with Roger Koerber for 11 years before his death. He was the co-describer of two of the great philatelic literature sales - the George T. Turner library in 1981 and the Herbert J. Bloch library in 1985; he wrote the preface for both. According to Hagan, Pfau’s dream was to become a literature dealer one day; unfortunately, he died less than two weeks short of 40. Most of Pfau’s library was sold by Koerber on June 20-21, 1986 and remainders on December 12-13, 1986 (lot 2688).

Roger A. Koerber (1934-1988) was a stamp and literature dealer and auctioneer. He started collecting stamps as a 15-year-old while recuperating from a heart artery transplant (he had a congenital heart defect), the world’s ninth recipient! He advertised himself as a professional philatelist since 1950. He was the founder of Roger Koerber, Inc. as well as Postilion Publications Philatelic Research Library, which made reprints of out-of-print philatelic literature. In later years, Koerber faced financial difficulties and left many consignors in the lurch. While the Turner sale helped Koerber make great returns, it was a temporary respite (see also Birch’s works which have more information provided to him by Hagan). Koerber had a personal library of his own (which included material from the Turner library) which, along with his retail stock, was sold by Charles G. Firby on August 29-30, 1988.

In his foreword to the Turner auction catalog, Koerber mentions that it was Don Pfau who suggested to use the services of Hagan in writing up the sale. Hagan’s deep knowledge of classic philatelic literature was well known because of his regular column on literature prices in the PLR. Hagan spent some 330 hours writing up most of the incunabula section, the Scott price lists and catalogs, Melville books, and many of the older books and periodicals.

In his aforementioned 1981 article, Trenchard thought that Turner belonged to 400 societies and specialist groups.

The sale realized over $250,000 with the Turner portion alone accounting for $172,000. See Hagan William. “The Turner Sale.” Philatelic Literature Review, Philatelic Literature Price Trends 30, no. 2 (2nd Quarter 1981): 99-102 and the prices realized to the sale for coverage of the auction. While the sale’s name was after Turner, Hagan estimates that Turner’s material comprised only 45% of the sale. Another 45% was Koerber’s retail stock and the balance of other consigners, including duplicates from Stanley Bierman.

Hagan confirms that this is the same incomplete Fournier album that Hartmann talks about in his interview to me which was published in the Q4 2020 issue of The Philatelic Literature Review. Purchased for $6,000, the album (no. 132 of 480) realized $3,100 in Hagan’s own auction in 2000.

The London Philatelist predates Philatelic Journal of India by 5 years. The first issue of the LP is dated January 1892 while that of PJI is January 1897.

Richard McPherren Cabeen (1887-1969) was a prolific writer and collector of early United States stamps, specializing in the United States 1851-1857 3¢ issues. The “Cabeen House” was owned by Richard and his wife, Blema B. Cabeen. It was bequeathed to the Collectors Club of Chicago in 1967. More information including photos be found on the Club’s website: collectorsclubchicago.org.

On February 19-20, 2000, Harmer-Schau Auctions Northwest, Inc. held the APS AmeriStamp Expo Auction featuring the literature collection of Hagan. For a report on this auction see Burega, Paul. “Literature Auction Prices Strong.” Let’s Look at Literature. Philatelic Literature Review 49, no. 2, whole no. 187 (2nd Quarter 2000): 76-80.