This article was first published as “The Bibliophile of London: David Beech” Philatelic Literature Review 71 no. 3 (Third Quarter 2022).

It has been edited and revised for publication online with two extra Q&As not originally published (on the first Crawford Festival and the Stuart Rossiter Trust) and many external links as well as links to my articles and new images.

It would be hard for anyone involved in serious philately not to know David R. Beech. I would like to think of him as one of the handful of academic and scholar philatelists around, a philatelist of philatelists, a philatelist par excellence.

Starting by becoming the secretary of his school stamp club at the age of 12, Beech has donned many hats over the years; chief of which was being the curator of the British Library (BL) Philatelic Collections for three decades from 1983 to 2013. For his services to philately, he was invested as a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) in 2012 (Figure 1). In 2013 he was the recipient of the Smithsonian Institution Philatelic Achievement Award for outstanding lifetime accomplishments in the field of philately. After his retirement from BL, he has been busy in philatelic journalism, research, and organization.

Readers of his works (and this interview) will note the precise and economic style of Beech, which says a lot about the person. It’s my pleasure to be interviewing him in the ‘bibliophile’ series.

Hello, David. Your interview has appeared at least twice in the pages of The Philatelic Literature Review.1 While I am extremely pleased that you have acquiesced for this interview, I will try to ensure my questions do not overlap those interviews. So, starting off, could you tell us more about yourself?

My full name is David Richard Beech and I was born on 1st February 1954. My parents, who married in 1950, were Frank Richard Beech and Eileen Elizabeth Beech (nee Harley). I have one younger brother and one younger sister. I was educated in Wilmington and Dartford in Kent.

You are the cousin of John Holman (Figure 2), editor of Gibbons Stamp Monthly 1985-1988 and British Philatelic Bulletin 1988 -2010. He was four years older. Did you get into stamp collecting because of him?

My cousin John Richard Holman (1950-2017) was the eldest of two sons of John and Florance Holman (nee Beech). Florance and my father were sister and brother. As you correctly guess John was a great influence being four years older. It was he who interested me in philately where we collaborated and collected similar subjects; mainly Great Britain local or private posts. John’s outstanding collection of these and other material from Great Britain and Ireland was donated to the British Library Philatelic Collections in 2019 by his brother Richard Holman.

You joined the London auction house of H.R. Harmer in 1970, when you were just 16. How did that come about?

I was the organizer of my school stamp club from the age of 12. I arranged a visit (probably in 1968) to the Mount Pleasant mail sorting office in central London which included going to see the Post Office underground railway (Mail Rail as it is known today) then still in full operation. In 1970 when I was 16 years old, I organized a public stamp exhibition at my school marking International Education Year. My interest was such that when a vacancy for a philatelic trainee occurred in the Expert Department of the London auction house H.R. Harmer Limited, I applied and got the job; in the first instance I was paid just £9 a week, but one was paid in philatelic knowledge too.

Tell us about your time at Harmers? By then, Cyril Harmer must have been running the firm.

Harmers was at this time still in the ownership of the Harmer family. Henry Revell Harmer RDP (1869-1966) had retired some years before and it was his son Cyril Henry Carrington Harmer RDP (1903-1986) who was the chairman. Mr. Cyril, as he was known to the staff, had joined his father in the business in 1921. After an initial period of about two years, I became an auction lot describer, which I would say is the best philatelic training and experience anyone could have, especially at the world’s leading auction house at the time. I still regard this experience as equivalent to a university degree in philately. Apart from lot descriptions one’s duties included meeting vendors and looking at collections potentially for sale or valuation. This was an education in dealing with people and sometimes managing their expectations!

My love of philatelic literature was gained when I became responsible for the H.R. Harmer reference library and the reference collection mainly of forgeries, reprints, etc. One was to meet many of the world’s leading collectors and dealers over the years including, during my first month with the firm, (and during the international philatelic exhibition Philympia held in London in 1970), the renowned American dealer Ezra Danolds Cole (1902-1992) of New Jersey.

I left H.R. Harmer Limited, at my bidding in 1979. By then the company had been renamed, for reasons I do not understand, Harmers of London Stamp Auctioneers Limited. By this time Cyril Harmer had retired and his younger brother Bernard Bertram Durkin Harmer (1914-2011) had taken over

I have remained friends with Bernard’s two sons Keith and Christopher and hope to have time to write a history of the Harmer family in philately.

What interests did you pursue in the intervening four years between Harmers and the British Library?

Before I joined the British Library in 1983, I was with Argyll Etkin Limited from whom I learnt a lot.

The great adventure of this period was that I was able to volunteer as the Controller of Exhibits for the London 1980 international philatelic exhibition, which was held on the first floor of the vast Earls Court exhibition center. The show had 4,500 frames of exhibits plus the literature class.

This was a more than a challenging experience which lasted over three months at a time before computers, the mobile phone, or emails, and with the complication of customs requirements for exhibits on entry and leaving the UK. In addition, security and transportation of exhibits, many of which were airfreighted (especially from eastern Europe where many commissioners did not attend in person), tested one’s management skills, not to mention endurance. Most days were of ten hours dedicated work usually seven days a week – exhausting but great fun, I learnt a lot and made many friends at home and abroad.

Your first book was the 1977 Falkland Islands the “Travis” Franks and Covers.2 How did this book get written?

The Travis book, which I wrote with my colleague Andrew Norris, was the result of a major find that I made in what was otherwise a rather ordinary small collection. The lady owner of the collection had brought it to Harmers’ New Bond Street office on May 10, 1977 for a formal valuation (for insurance purposes). This was to take place a few days later, and as such it was not inspected closely on receipt.

In the words we used in the book,

A few days later in the Expert Department, David Beech who was examining the collection was stunned to discover among some loose covers a superb example of the very rare black “Frank” of the Falkland Islands impressed on a most attractive wrapper” dated 1871. Colleagues gathered round following my shouts of delight and before long a cover with the black “Frank” was found as well as other significant covers from and to the Falkland Islands. The covers were addressed to George Traves (1844-1912) the Postmaster from 1873 to 1878, or to members of his family, in the Falklands or to Tetney Lincolnshire, UK.

It was one of the most memorable and exciting days of my life. The subsequent sale of this material took place on 1st December 1977 and realized sufficient funds for the lady owner to cover much of the purchase price of a new home.

How did you transition to taking up the role of curator at the British Library (BL) Philatelic Collections? (Figure 3)

Looking back to the time I joined the British Library in 1983 I now fully realize that the curatorial role was one which suited me very much; I took to it like a duck to water. It offered a unique opportunity to study, offer interoperation, context, and communicate with philatelists about philately and BL’s collections of philatelic material and philatelic literature on a worldwide basis. In later years colleagues were prone to describe me as a “Curator’s Curator”. In fact, we should go back to the time of my first visit to see the Tapling Collection on exhibition which must have been when I was about 12 years old; I came away thinking that the job of looking after it would be an ideal career. So, the one job in the world which was my ideal I got to do for thirty years.

The Curator and Head of the Philatelic Collections in 1983 was Robin “Bob” F Schoolley-West (1937-2012) (Figure 4). Bob was something of a pioneer in the greater understanding of philatelic conservation and the British Library jointly with the American Philatelic Society published the book, The Care and Preservation of Philatelic Materials, in 1989.

A junior curator, Ms. Helena Whiteside, mainly managed the extensive UPU Collection which took up nearly all of her time given the large number of new stamps being issued worldwide. Following her departure to another department within the British Library, John N. Davies (1935-) a fine philatelist and curator joined us in 1986 to manage the UPU Collection and the Crown Agents Philatelic and Security Printing Archive. Following John’s retirement in 1993, Rodney V.M. Vousden was appointed and following him the current lead curator, Paul Skinner (1959-), was recruited in 2004.

I became the principal curator and Head of the Philatelic Collections on the retirement of Bob Schoolley-West in 1991.

Having visited the British Library once, I can say it is one of the greatest treasure houses of the printed work in the world. Most people know the library for housing the Tapling and Crawford collections. Please tell us more about these two collections.

The Tapling Collection of postage stamps and postal stationery was formed by Thomas Keay Tapling MP (1855-1891) and bequeathed to the Nation. It is a world collection and is the only major collection formed in the 19th Century which is still intact. It needed rearrangement following many acquisitions by Tapling which included much of the significant collection formed by the brothers Gustave Caillebotte (1848-1894) and Martial Caillebotte (1853-1910) which was acquired in the last years of Tapling’s life.

This task was undertaken by the first curator Edward (later Sir Edward) Denny Bacon KCVO, RDP (1860-1938) between 1892 and 1899 with the assistance of Miss Jane Hamilton (1874-1957) (later Mrs. Herbert M. Ellis). The Collection remains in the same form today, so well was it completed. The postage stamps are on about 4,500 pages and it contains most of the great philatelic rarities of the first 50 years of issues from 1840 as well as numerous shades. It is mainly unused and is missing little of the basic stamps. It is truly a world reference collection, an indication of the state of knowledge and of philatelic fashion at the time.

The Crawford Library of philatelic literature was formed by James Ludovic Lindasy, 26th Earl of Crawford (1847-1913) and was bequeathed to the nation. It is about 95 percent complete of all known philatelic literature from the first separate item published in 1861 to about 1912-13. It includes the philatelic libraries of John Kerr Tiffany (1842–1897) of St Louis, United States and Judge Heinrich Fraenkel (1853–1907) of Berlin, Germany. Its catalogue was compiled to a high standard by Edward Denny Bacon for Lord Crawford and published in 1911.3

I have described the Earl’s library and its history in an article “The Crawford Library of Philatelic Literature at the British Library and for the World in Digital Form” which appeared as a supplement to The London Philatelist of March 2016 (Figure 5).4

The British Library’s Philatelic Collections is not just the two mentioned collections, is it? You have written a book on this called A Guide to Philatelic Research at the British Library published in 2019.5 What can you tell us about the other philatelic material in the BL?

The BL’s philatelic collections are 76 in number, received as donations, bequests, or transfers from British government departments or agencies between 1892 and 2019. These are both major collections and archives as well as smaller specialized collections; approximately 8,000,000 items in total. My guide that you mention gives some essential details about them and how they may be seen and used for research. These collections are the world’s largest philatelic holding for exhibition and study. They cover probably all countries that have issued postage stamps, postal stationery, revenue stamps, telegraph stamps, etc. The collections from British Government departments or agencies are Archives of Public Record (protected) status. I could go on for pages here – so best get the guide!

In your time at the BL, you were involved in conserving the Crawford Library. It was in “a bit of a mess then.” Why was the conservation needed and what were your experiences around it?

The work to preserve and make better available the circa 4,500-volume Crawford Library was a 30-year project (thus taking all of my years at BL) and which still continues today. It was, as you say, bit of conservation mess, when I first set eyes on it in 1983, for responsibility for the BL’s printed book collections was mainly organized by language and as it contains volumes in many languages, responsibility was unclear. I took the view that I would take the responsibility for it within the Philatelic Collections department.

Much of the library is printed on wood pulp paper so common from the mid-19th Century onwards. Such paper is usually acidic causing it to turn brown and in time crumble. The conservation treatment necessary is to deacidify the paper and, if necessary, laminate and rebind. In addition, such volumes were invariably microfilmed. The Tiffany volumes were bound in poor quality leather and almost all have been rebound in blue buckram.

You wrote the Preface to the revised edition of the Crawford Catalogue that was published in 1991. What are your recollections about this reprint?

The Crawford Library Conservation Project started in 1985 and by 1990 much of the “in danger” volumes had been conserved. It was then time to look to make the Crawford Library more easily available for research and scholarship. With the centenary of the Tapling bequest in mind in 1991 we began to look at publishing a revised edition of Bacon’s 1911 original work with its 1926 Supplement and 1938 Addenda. In collaboration with Dr Arthur H Groten of The Printer’s Stone Limited of Fishkill, New York, USA, Catalogue of the Crawford Library of Philatelic Literature at the British Library was published with the Preface you mention and the British Library shelfmarks added. It was launched at a reception given for the centenary of the Tapling bequest on October 2, 1991.

Many (but not all) of the books in the Crawford Library can now be accessed through the Global Philatelic Library. This is a boon to many philatelists like me and helps in the democratization of knowledge. What was your role in this?

I was the instigator of the Crawford Library Conservation Project, and The Crawford Library Digitisation Project. The latter was still underway at the time of my retirement at the end of March 2013 and the very considerable work on behalf of BL in taking that project forward with our partners the British Philatelic Trust (who provided the bulk of the Project’s funding) and The Royal Philatelic Society London (RPSL) with its Global Philatelic Library (who provided infrastructure and the migration of images and some metadata, etc.), was undertaken by my successor curator, Paul Skinner.

Something in the region of 600,000 pages of text (or about 50 percent of the total) have been released so far. The constraints are that many of the volumes are still in copyright, and that they were not microfilmed during the Conservation Project from which digital images were made. When the microfilming was being undertaken, we had little idea of how the then future internet would transform the availability of information. Much work needs to be undertaken to complete the task despite it being the largest philatelic digitization project undertaken anywhere to date.

In the preface to his 1926 Supplement to the Crawford Catalogue, Bacon says, “The "Catalogue" and "Supplement" now give a full description of every work contained in the library down to the dates to which the lists were carried: i.e., to the end of 1908 for PART I (books) and to the end of 1906 for PART II (journals)…It is a source of much regret to me, that owing to the Great War and the difficulty of obtaining descriptions of publications issued abroad during that period, I have found it impossible to continue the catalogue to the present year. I must, consequently, leave to others the compilation of a list of the philatelic literature that has appeared since the dates at which the two parts of the catalogue terminate.”

Now, Lord Crawford continued collecting until 1913 and the British Museum would have added some titles subsequently. Have these uncatalogued works also been catalogued and/or digitized?

Your point is a good one, the answer to which is complicated. As Bacon suggests, the advent of the Great War in 1914 was a major disruption to the management of the Crawford Library. It should be remembered that the original title of the 1911 Crawford Catalogue was Bibliotheca Lindesiana Vol. VII A Bibliography of The Writings General, Special and Periodical forming the Literature of Philately. Thus, it is firstly a bibliography of everything that is reported to have existed and secondly a catalogue of the Earl’s philatelic library. Bacon, who you quote, is referring to some extent to his work for the function of the book as a bibliography.

I do not know of anything added to the Crawford Library after 1913; such would have been added to the library’s general printed book collection. Where a journal was in progress and was still being published in 1907 new numbers were still added to the run; only the details of volume/year, dates, etc. have not been added to the Catalogue. While Bacon continued to be involved with the Crawford Library after the Earl’s death in 1913 much of his time was taken up with his new duties as Curator of the Royal Philatelic Collection for King George V (1865-1936) from that same year 1913.

It is worth mentioning that philatelic literature was always acquired by the BL anyway and it is not restricted to being in the Crawford Library. For example, I have written about and listed the stamp albums in the printed book collection for The Philatelic Literature Review in 2005.6

You point out correctly that more work needs to be carried out here for full understanding and clarification.

This is a pointed question. The BL has so many different departments ranging from the arts to business to history to law to social sciences. What would you say is the pecking order of the Philatelic Collections group? For example, when you joined there were three curators and now there are only two.

I feel that it is always a mistake to attempt to compare libraries or departments within a library. It is not a competition as to who holds the most books, or the oldest books, nor the rarest books, etc. Such considerations are unhelpful and are usually made in ignorance of key factors. Every subject area or object type is valued within BL. Many collections have just one or two curators and the dynamics of access and management are often very much different from department to department.

You refer to the staff numbers reducing from three to two curators. This occurred as we made a policy decision not to continue mounting the UPU Collection which was little used for its modern issues. Curatorial time could be better spent on other work of value to researchers.

I place the onus much on the special or select community served by any such department or collection area and therefore how seriously it is taken by a governing board or management. I never refer to philately as a hobby, I prefer to use the word “subject”. Perhaps readers should refer to my A Guide to Philatelic Research at the British Library which includes, as Appendix 1, the third version of my “Philatelic Research – A Basic Guide”.7

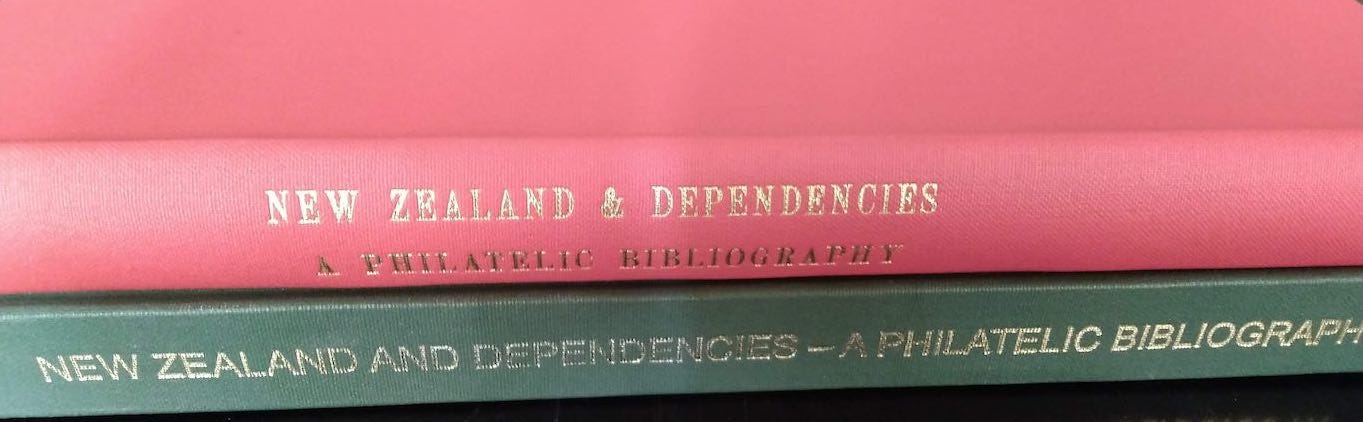

In 2004, you co-authored the book New Zealand and Dependencies – A Philatelic Bibliography with Allan P. Berry and Robin M. Startup. What was the genesis of this work?

The bibliography came about when my good friend Allan Philip Berry (1937-2010), a great collector of New Zealand philately and its philatelic literature, not to mention being a sometime editor of The Kiwi, the journal of The New Zealand Society of Great Britain, decided that he would like a catalogue of his library. Allan and I had become friends during the time that we were organizers of the independent autumn national exhibition, the British Philatelic Exhibition, held in London in the 1970s. As I had been at the BL for some years by then, I agreed to assist him in the task. Given that Allan possessed a lot of material, we decided to extend the task in 1988 to be a bibliography of all New Zealand philately with the prospect of its publication. We had little difficulty in persuading Robin McGill Startup RDP (1933-2012) to join us in the endeavor.

The book has an interesting story in that another edition of just 16 was published by the British Philatelic Trust the earlier year. Would you like to go on record on that?

The original intention was for the British Philatelic Trust to be the publisher. It mismanaged the project and let production costs – for which it alone had control – get out of hand. This resulted in the trustees deciding to produce the first edition dated 2003 – not formally published – in a limited edition of just 16 (numbered) copies and bound in red buckram.

To the three authors, having put many years work into the project (in my and Allan Berry’s case some sixteen years each, for Robin Startup much longer) this was unacceptable. This resulted in a second edition dated 2004 (improved and expanded from the first edition) being published in Thames, New Zealand by Allan P Berry & David R Beech. This second edition (bound in green buckram) was reset to avoid any question of typographical copyright belonging to the British Philatelic Trust (Figure 6).

Would you call yourself a bibliophile? If yes, tell us more about your library.

I would refer to myself as a bibliophile and I do collect a limited amount of philatelic literature. But with both BL and RPSL in London, access to texts and volumes is a comparatively easy matter. You do not have to have a library to be a bibliophile. Perhaps the most valued item in my library is a complete set of The London Philatelist.

I have been greatly privileged to have known and worked with Dr Robin Alston OBE (1933-2011) who was a brilliant and passionate senior curator at BL and Editor-in-Chief of the union catalogue the Eighteenth Century Short Title Catalogue of printed books predominantly the hand-printed text in English before 1801. Robin took time to introduce me to bibliography, classic and modern librarianship, often by taking me into the book stacks to look at BLs extensive collection of incunabula (books printed before 1501), or of the old Royal Library (transferred by King George II in 1757), or that of King George III (the Kings Library). This rare experience has been invaluable in understanding something of the printed book, its paper, its meaning, its importance, its construction, its binding, its use, its cataloguing, and its care.

Do you collect stamps or postal history? Have you exhibited them?

Not now and so I do not exhibit. My interest is in philatelic knowledge of all kinds and areas, its understanding and context in history be it political, economic, or social.

Many bibliophiles rue the fact that the general collector of stamps and/or postal history does not give enough importance to philatelic literature; much to their own detriment. On the other hand, collectors would rather spend the limited resources (money but also time) at their disposal on their collection. How can we get collectors more interested in literature?

What you are describing is the difference between a stamp collector and a philatelist. One collects with minimal need for literature and the philatelist collects (but not necessarily; rather like me) but studies the philately and its historical background etc. which does require literature. The subject of philately can be just what you want it to be. I suppose that the answer to your question is that one should always encourage a stamp collector to become a philatelist with success depending on intellect, time, and pecuniary considerations.

You were the President of RPSL (Figure 7) between 2003 and 2005. How did you get involved with the Society? Tell us more about your time as a member and later President?

I became a member of The Royal Philatelic Society London in 1983 and was elected a Fellow in 1990. I joined the Council in 1993 and was elected a Vice-President in 1999 becoming President from 2003 to 2005.

It was a time of careful change and we had established a Management Committee to deal with matters that required a discussion more urgently than the regular Council meeting permitted; as Vice President I was the first Chairman of that committee.

It was also established that, given a reducing number of people in philately, the Society would seek to increase the number of members to 2,000 from about 1,400. This would much aid its economics given the cost saving and efficiency given by computerization. Further the society would have a good future, if numbers continued to reduce around the world in general, to have at least 2,000 members. I drove this policy and the Council readily agreed that if the number of serious philatelists worldwide reduced to say 10,000, the Society would prosper if we had 2,000 to 5,000 of them as members. The adoption, or continuation, of serving serious philately at high standard for everything we do means that membership is strong and growing. In modern terms this identifies our ‘brand’ area within philately.

I have served on a number of Committees of the Society including those of Fellowship, Crawford Medal, Tapling Medal, Museum and Archives, Library, Finance, and Publications.

During my term as President, we made permanent the previously occasional practice of holding a reception after meetings of Fellows and Members. This transformed the feel of Society meetings and added much to their friendliness. I travelled to Sydney, Australia in 2005 for the Pacific Explorer exhibition where a lunch was held for all members of the various Royal philatelic Societies around the world (Canada, Cape Town, New Zealand, Victoria, and Zimbabwe); all except the last was represented. Perhaps the event of lasting importance during my term was the decision in 2004 by Fellows and Members to admit to membership all interested in philately and not to exclude professionals.

As is usual four years after my Presidency, I left the Council but returned to become the Hon Librarian from 2014 to 2015 before passing on that baton to Ben David Palmer (1976-).

In June 2022, on the occasion of the first annual Crawford Festival organized by the RPSL, you not only gave the keynote address but also brought out a 40-page book – A Bibliography of the Philatelic Writings, Digital and Sound Recordings of David R Beech from 1970 to Date. Tell us more about both.

It was a great privilege to give the keynote presentation '“Crawford in Context: the place of the 26th Earl of Crawford in Philatelic History” on June 28, 2022, during the first Crawford Festival. This came about because I was responsible for the Crawford Library during my years as curator at the British Library when I made a special study of the most notable 26th Earl in this and his wider philatelic and academic context.

The two-day event was not available to remote participants at the time, but it was recorded, and I understand that the RPSL, the Festival’s organizers, will be making it available in due course (link to the video above; poor audio though).

My new monograph, a self-bibliography, was compiled over some years to record my written, sound, and digital recorded work, mainly because, after some fifty years, I have a need from time to time, to find what I said some years before. The occasion of the first Crawford Festival seemed a good time to publish.

You were a trustee of the Stuart Rossiter Trust which has published some important books on philately and postal history, especially on subjects of the British Commonwealth. From 2000 until 2006, the Trust published eight volumes of the Rossiter Postal History Journal containing long-form articles on matters of postal history interest. Why was this discontinued? Secondly in late 2018, the Trust published its first online book – The Sub-Office Postmarks of Sheffield by Frank Walton; this led to some heated discussions in the pages of The London Philatelist in 2019 on the future of publishing and whether digital-only was the way to go. Could you summarize your current views on this subject?

I first met Percival Stuart Bryce Rossiter (1923-1982) in the early 1970s. He was a passionate philatelist and postal historian and an outstanding editor of The London Philatelist. He was a true gentleman; his early death was a great loss.

I became a Trustee of the Stuart Rossiter Trust (SRT) in 2002 (to 2010) at the invitation of the then Trustees and became its chairman. The good work of the Trust had long interested me as well funded publishers of monographs about postal history subjects. It had, and still has, a wide interpretation of postal history in a modern sense; that is that it sees the subject as a part of wider history and so potentially appealing to a wider audience.

The publication of the Rossiter Postal History Journal from 2000 to 2006 was an attempt to make available texts shorter than a full monograph but worthy of appearing in print. Unfortunately, it proved difficult to market and so came to an end.

While I was not involved in the on-line publication of the late Frank Walton’s, The Sub-Office Postmarks of Sheffield, it was a notable endeavor and a success. One of the major issues with any philatelic publishing is: how many do we print and be able to sell? This got round that question and made possible a second edition following much feedback. The question that followed in the pages of The London Philatelist in 2019 centered on the long-term survival of the work. Fortunately, the British Library collects UK and Ireland digital publications (legal deposit copies) for permanent retention and availability.

To me one of the most pleasing grants that SRT made during my time as chairman was to The History Press Ltd. for the book Fleeing from the Fuhrer by Charmian Brinson and the late William Kaczynski. It has now been published in three languages. William, who became a good friend, and I enjoyed promoting its sales to a wider audience than the philatelic one.

Are/were you involved in organized philately in other ways?

Over the years I have been involved with many organizations (Committees, Councils etc.) and these have included: the British Philatelic Federation, the Association of British Philatelic Societies, the British Philatelic Exhibition, the London 1980 international philatelic exhibition, the Philatelic Writers Society, the National Philatelic Society, and most recently the W4 Philatelic Research Group.

Apart from the RPSL, you seem to have a special relationship with the American Philatelic Research Library. In 2001, you visited the place where the philatelic center now stands before it was even bought over by the APRL; it was a matchbox factory! On October 28, 2016, during the Grand Opening of the library, you were called upon to give the Dinner Keynote (see link above).8 Tell us more about your relationship with the APS/APRL over the years.

It is not at all surprising given my curator post at BL that I would enjoy special relations with APRL. Relationships are about people and so regular contact, by means of the then new email system, with the APRL librarian Virginia L “Gini” Horn (1951-2022)9 (Figure 8) was normal. She was in post from 1984 to 2010. We were in contact quite frequently and discussed matters of policy, conservation, books new and old, cataloguing, research, librarianship, and bibliography etc. and assisted each other with some of the more challenging enquires - not to mention philatelic gossip!

The APRL is an outstanding library for several reasons. One: is that it has a large collection of books and periodicals covering any philatelic subject, perhaps the world’s largest. Two: it is mainly an open access library which permits users to come and look at the shelves. Three: it is that its staff are knowledgeable about philately, about how the library works and most helpful. Four: is that library space is ideal and this I could see when I saw it empty and undeveloped in 2001 in company with Gini Horn and Bob Lamb (Figure 9).

I have been most pleased to make occasional contributions to The Philatelic Literature Review for it is well edited, maintains high standards and is an outstanding periodical for literature and many aspects of research and scholarship. It is a journal of record.

On the subject of libraries, what are your thoughts on their future? What should philatelic libraries do to pivot themselves into the coming decades?

More of the same, taking advantage of digital opportunities and co-operating with other libraries worldwide. Philately is international so some big thinking is a good approach.

So, would you say you are fairly satisfied with the current state of existing philatelic libraries?

One can always do better, but with a mainly hard-working volunteer work force (usually most dedicated) and limited financial resources one must be careful with any comment. Setting these considerations to one side, I would say that not enough is put into the understanding of conservation and the conservation (mainly binding and paper conservation etc.) itself. Storage space and cataloguing are major factors, and this leads us back to finance – so perhaps another challenge is to find funds.10

What areas of philately are your currently working on?

These days, apart from my Past President role at the RPSL which is to take a statesmanship approach to issues and to offer help and advice, and aiding BL’s philatelic collections by being available for consolation and to give advice and occasionally undertaking some tasks. In addition, I am a member of the Advisory Council of the British Library Collections Trust.

I largely limit myself to research projects and currently the main ones include Mauritius: 1847 "Post Office" issue printing plates; The H.R. Harmer auction houses; Shanahan's Stamp Auctions Limited; Kenya, Uganda and Tanganyika: 1954-59 issue; British philatelic history; Hejaz: 1916 issue and its literature.

Two interviews appeared in quick succession in 2001 and 2002; the subject matter of these were specific to the philatelic collections of the British Library and the libraries of the Royal Philatelic Society London and the American Philatelic Research Library. See Farmer, Bonny. “A Royal Visit. An Interview with David Beech.” Philatelic Literature Review 50 no. 3 whole no. 192 (3rd Quarter 2001): 195-199 and Anon. “The British Library Philatelic Collections. An Interview with David Beech, Curator and Head of the Philatelic Collections.” Philatelic Literature Review 51 no. 1 whole no. 194 (1st Quarter 2002): 12-14.

Norris, Andrew, and David Beech. Falkland Islands The “Travis” Franks and Covers, London: Harmers of London Stamp Auctioneers Limited, 1977

This catalog is well known as the “Crawford Catalogue”. A formal bibliographic description would be: (Bacon, Sir Edward Denny). Bibliotheca Lindesiana Vol VII: A Bibliography of the Writings General Special and Periodical Forming the Literature of Philately. Aberdeen: University Press, 1911.

This work and well as the 1991 revised edition of the Crawford catalogue can be freely downloaded from the Global Philatelic Library website. See globalphilateliclibrary.org/bl_crawford/crawford_about.html.

Beech, David R. A Guide to Philatelic Research at the British Library. London: The Author, 2019

Beech, David R, “Stamp Albums in the Printed Book Collections of the British Library.” Philatelic Literature Review, 54 no. 1 (1st Quarter 2005): 16-24

The Basic Guide is freely available on the RPSL website. See rpsl.org.uk/Portals/0/RPSL/Beech_David_Philatelic_Research_2019.pdf.

Beech’s witty yet thoughtful keynote can be seen on the American Philatelic Society’s YouTube channel: youtube.com/AmericasStampClub and specifically here: youtube.com/watch?v=hXXsnmxq3iY. A synopsis of it can be read in Anon. “Respected Curator Praises Library, Urges Digitization for the Future.” Philatelic Literature Review 65 no. 4 whole no. 253 (4th Quarter 2016): 264-266.

I was personally shocked to know that APRL’s greatest librarian of 25 years, “Gini” Horn is no more. The pages of the PLR will show that she was as good a philatelic literature bibliographer as any. I had hoped to do an interview with her. She died 21 February 2022 at Providence Place Senior Living in Chambersburg, PA, US. An obituary was published as “In Memory of Gini Horn” Philatelic Literature Review 71 no. 1 whole no. 274 (1st Quarter 2022): 15-16. Online obituaries appear here: stamps.org/news/c/news/cat/aps-news/post/in-memorium-gini-horn and here: fcfreepresspa.com/virginia-l-gini-horn-obituary-19512022.

In his keynote, Beech says that the conservation, microfilming, and digitization of the Crawford Library cost £3 million and that getting this sum out of the British government was a “tough act”!