The Abyssinian Expedition of 1867-68: Letters to France

Over-stamping and confusing future postal historians

This article was was originally published as “The Abyssinia Expedition of 1867-68: Letters to France” in The London Philatelist 133 whole no. 1516 (June 2024): 251-263 and with the same title in India Post 58 no. 3 whole no. 232 (2024): 104-113. It is a co-publication between The Royal Philatelic Society’s The London Philatelist and the India Study Circle for Philately’s India Post.

The Abyssinian Expedition, lasting from late 1867 to June 1868, was a short military campaign of the Victorian era lasting just a few months. It is perhaps not as well-known today as many others mainly because there was little actual fighting and hence few casualties (just two dead on the British side but about 700-800 on the Abyssinian); it is an unfortunate truth that campaigns with lots of battles and much killing are the ones that remain etched in public memory generations after.

For about 50 years either side of this Expedition, the British Empire’s powers–imperialistic, militaristic as well as economic–were at their zenith, and this expedition, in its audacity and without any regard to costs (£8.6 million),1 could not have been mounted by any other country at that time. Due to the harshness of its terrain and lack of any infrastructure such as ports along the Red Sea or roads on land, Abyssinia was a difficult country to invade. But invaded it was with an Anglo-Indian army of 14,214 men, 26,254 camp followers and 37,143 animals including 44 elephants (Raugh 2004, pp.3-4)! The reason for this was not territorial annexation but the rescue of British (including the British Consul) and European prisoners held captive by an increasingly unstable Emperor Theodore (Tewodros) II. And the restoration of British pride and prestige, of course.

From a postal history perspective, only about 120 postal history items from and to the Expedition are thought to exist in private hands; some have not been seen for decades.2 Almost all are covers and most are missing their contents. In the main, the covers are generally found in ‘average’ to ‘good’ condition; just a few covers can be classified as ‘fine’ or ‘very fine’ in the traditional philatelic sense.

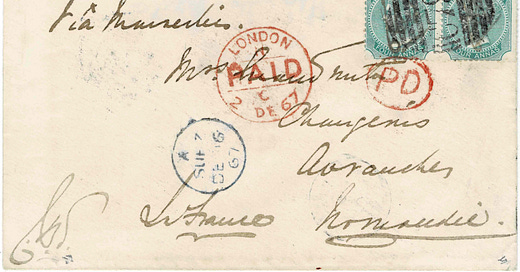

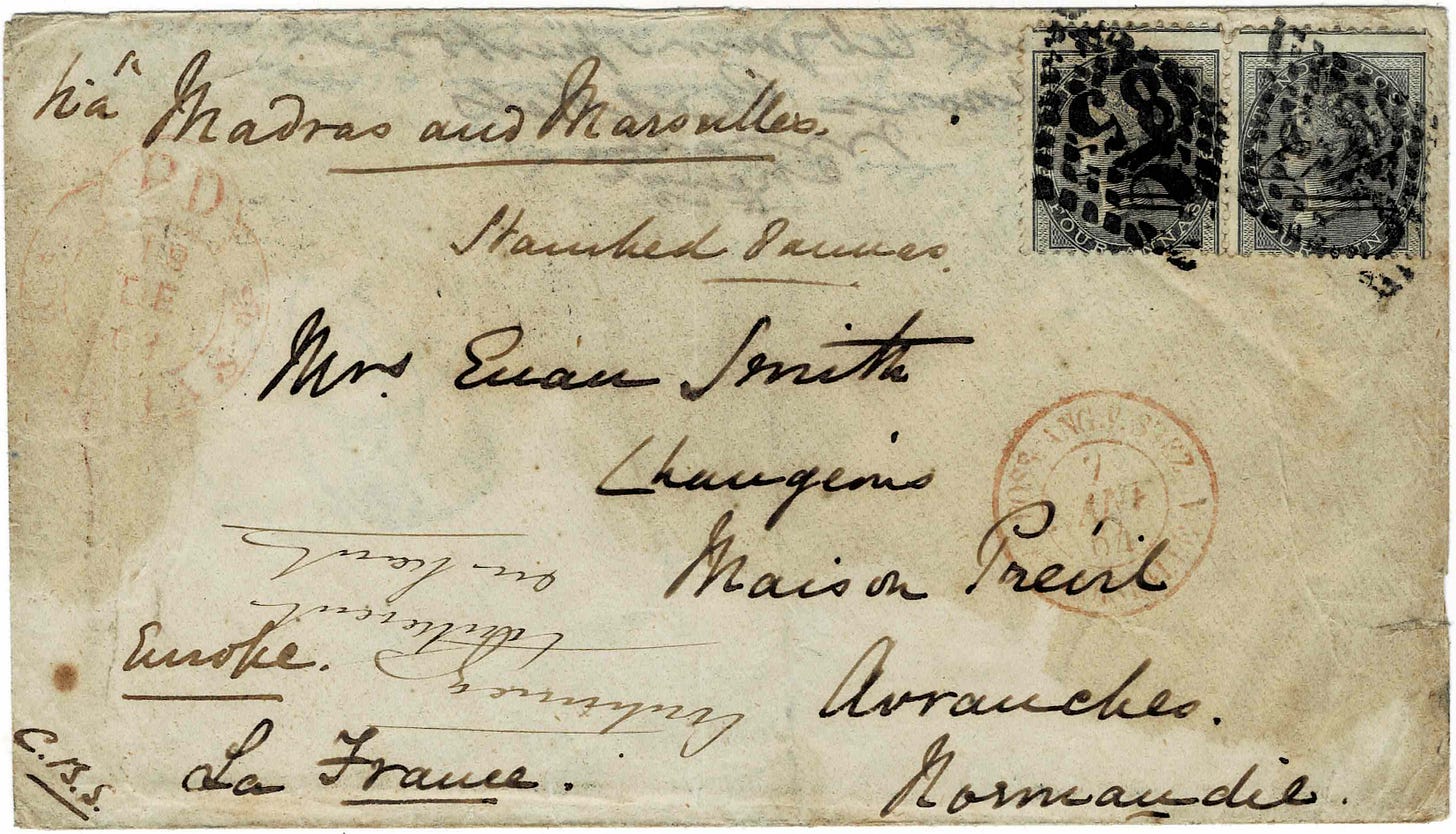

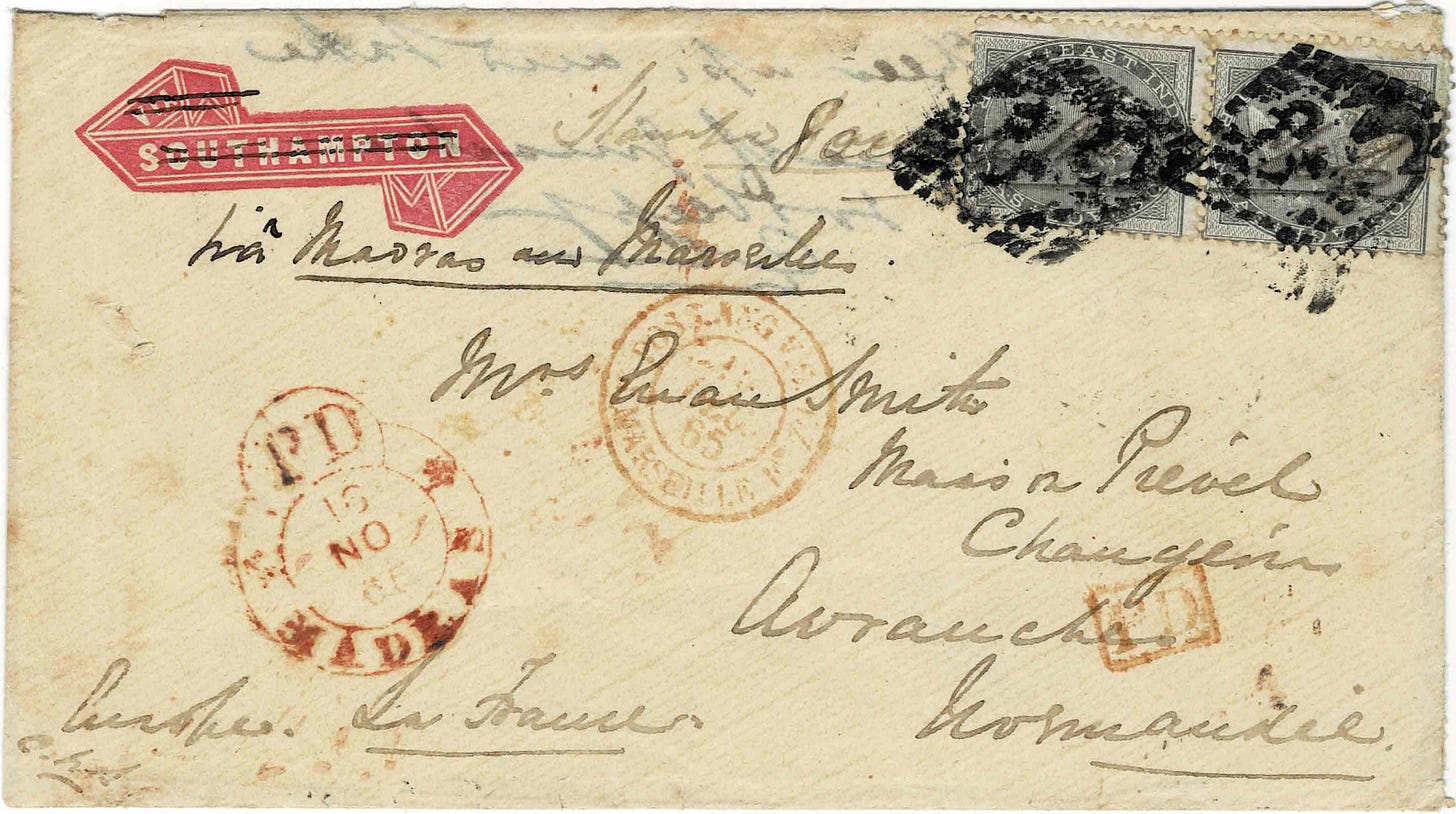

Further, most letters are, quite understandably, to or from either Great Britain or India. Of the six outgoing letters known to France (all illustrated here), five are from the Euan-Smith correspondence.3 All five are franked with stamps totalling 8 annas; this is a rate which never existed and has confused previous researchers (for instance, Sciaky 2003, p.112) into believing that it was the correct usual rate to France.4

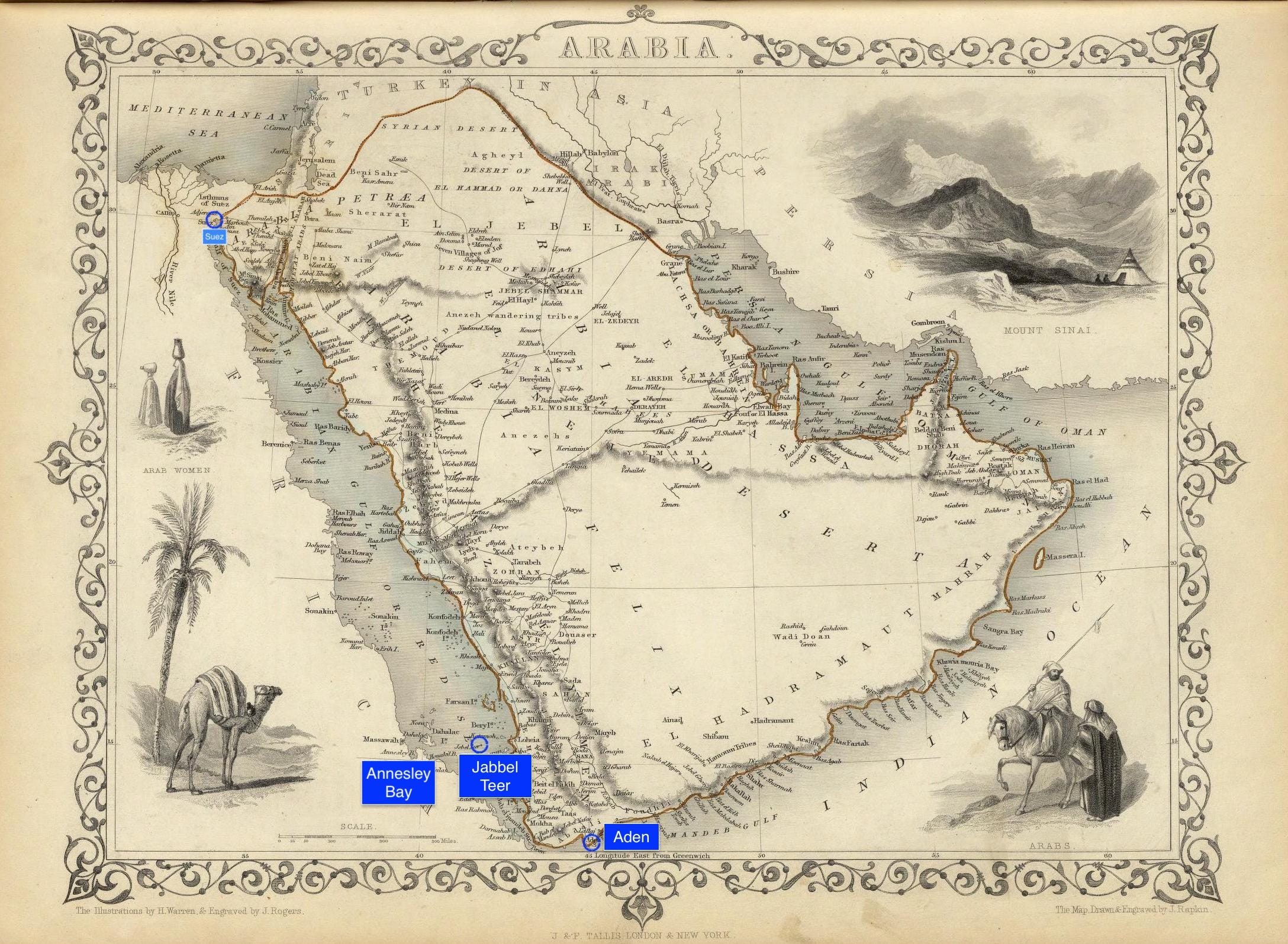

Mr. Smith Goes to Abyssinia5

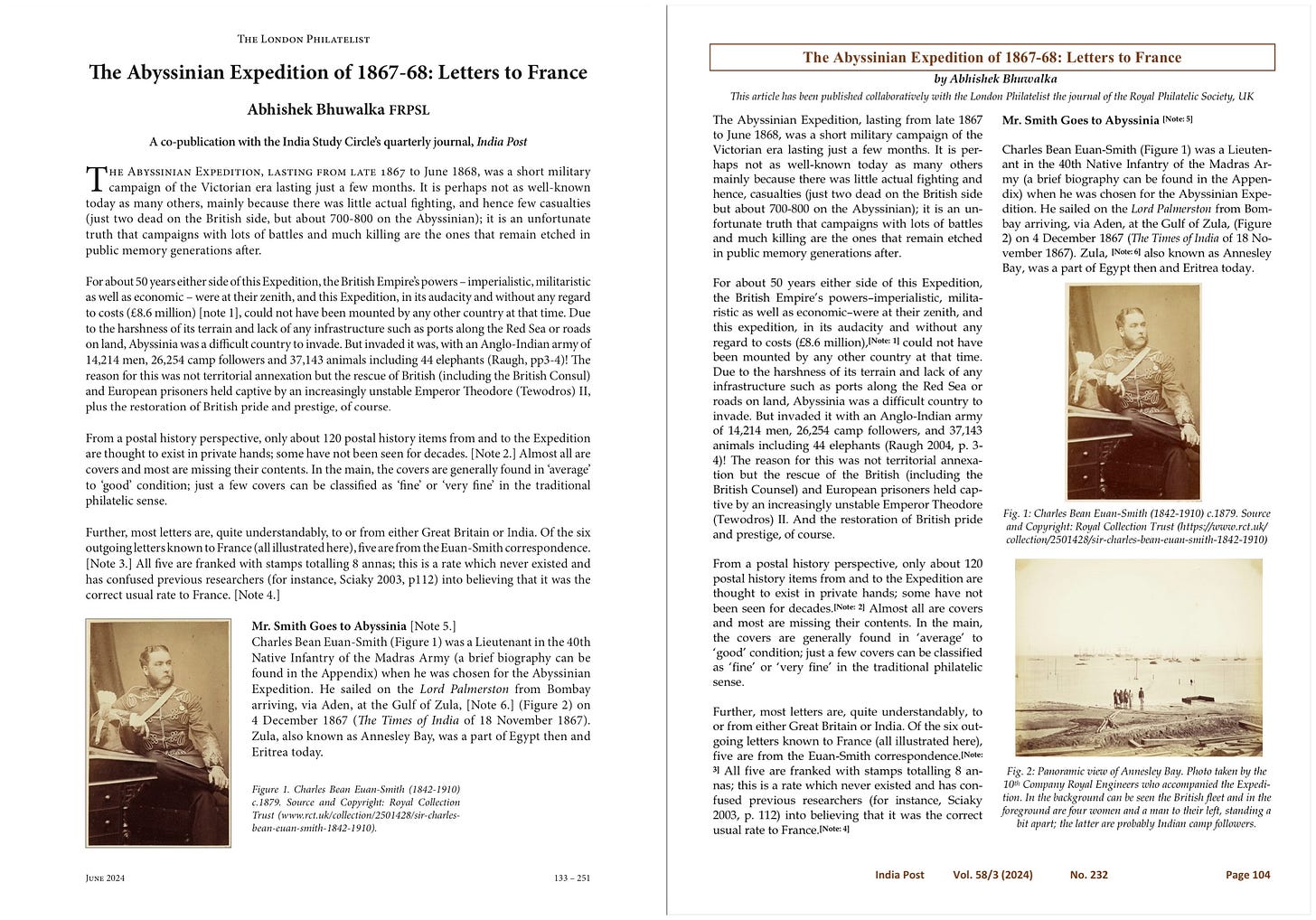

Charles Bean Euan-Smith (Figure 1) was a Lieutenant in the 40th Native Infantry of the Madras Army (a brief biography can be found in the Appendix) when he was chosen for the Abyssinian Expedition. He sailed on the Lord Palmerston from Bombay arriving, via Aden, at the Gulf of Zula,6 (Figure 2) on 4 December 1867 (The Times of India of 18 November 1867). Zula, also known as Annesley Bay, was a part of Egypt then and Eritrea today.

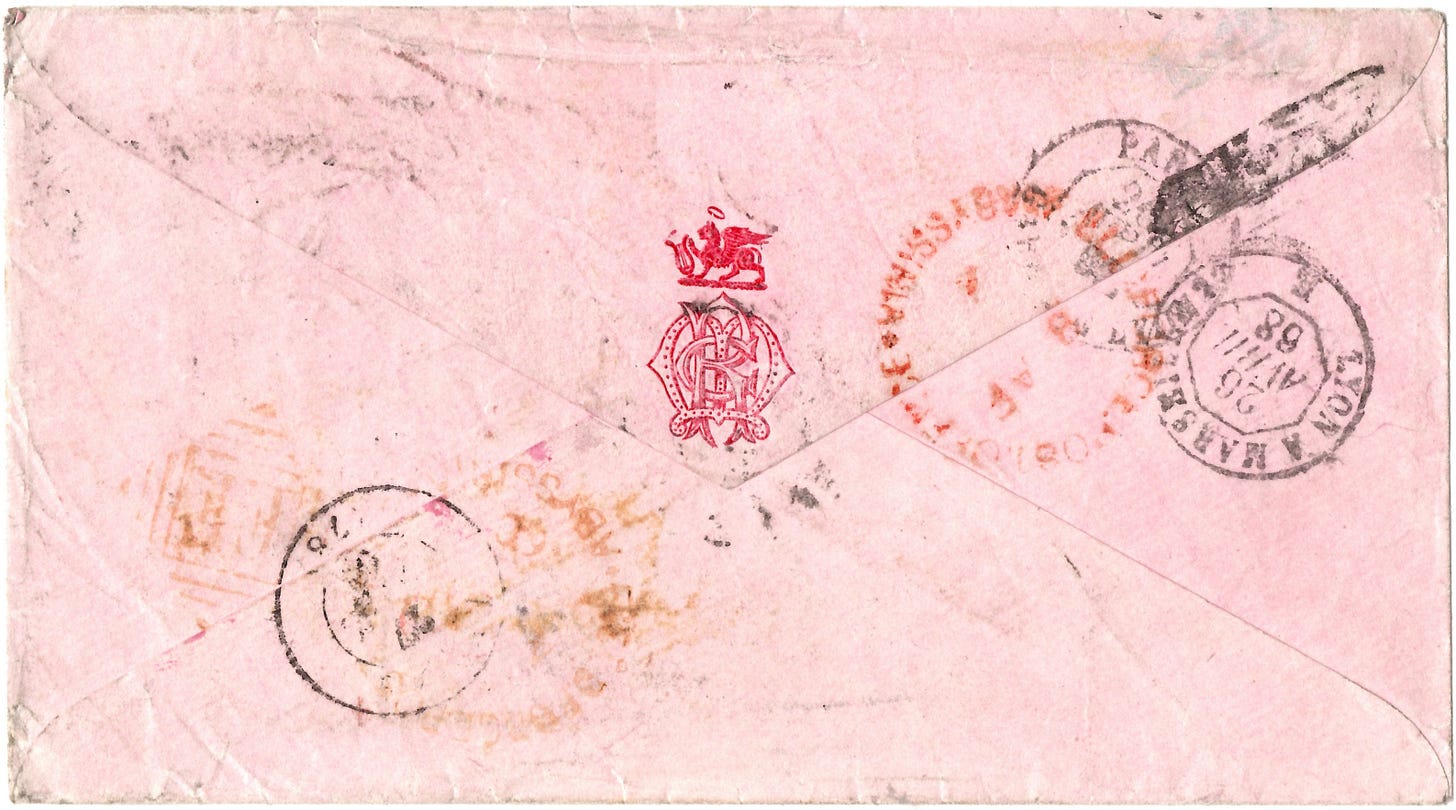

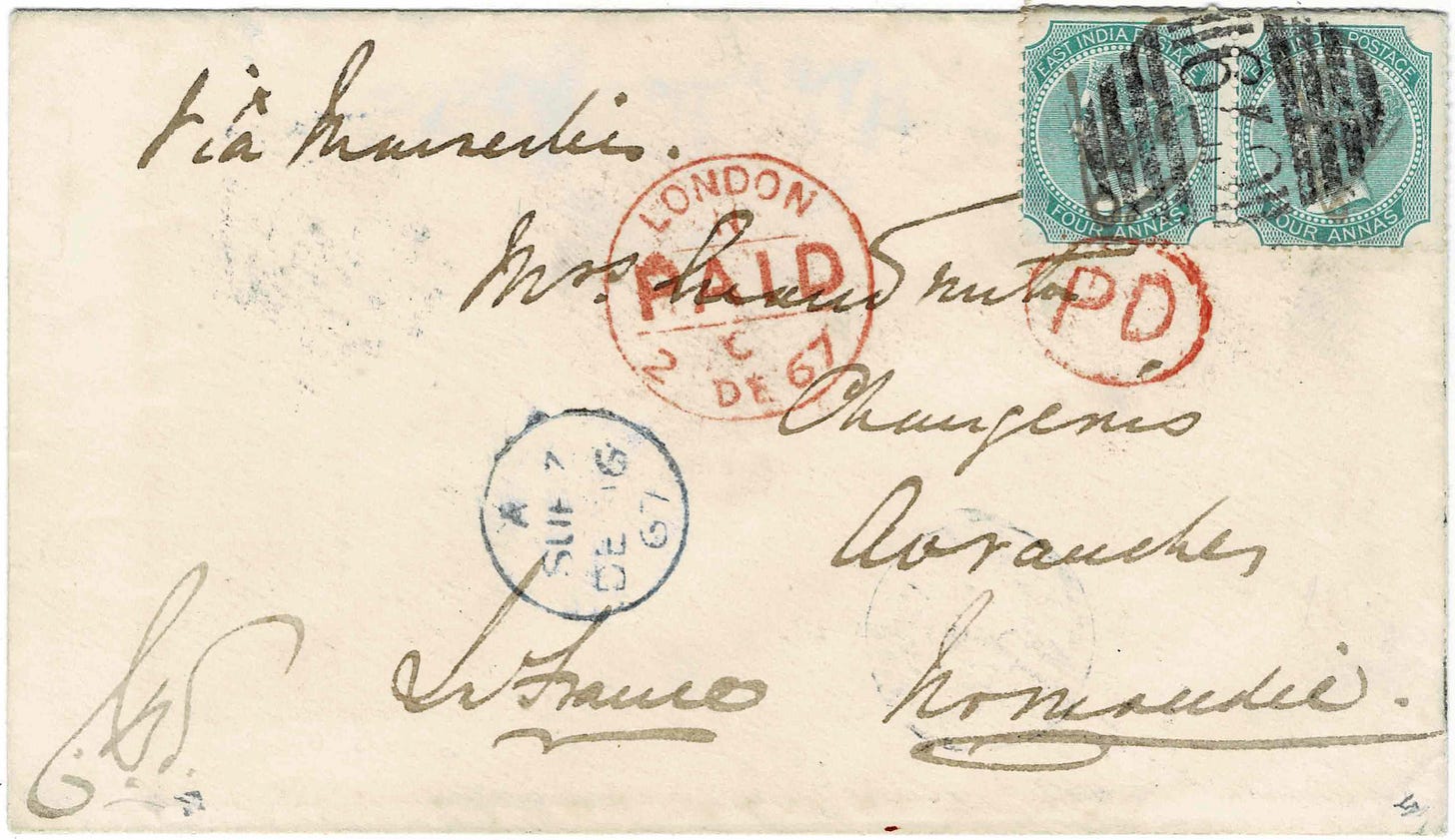

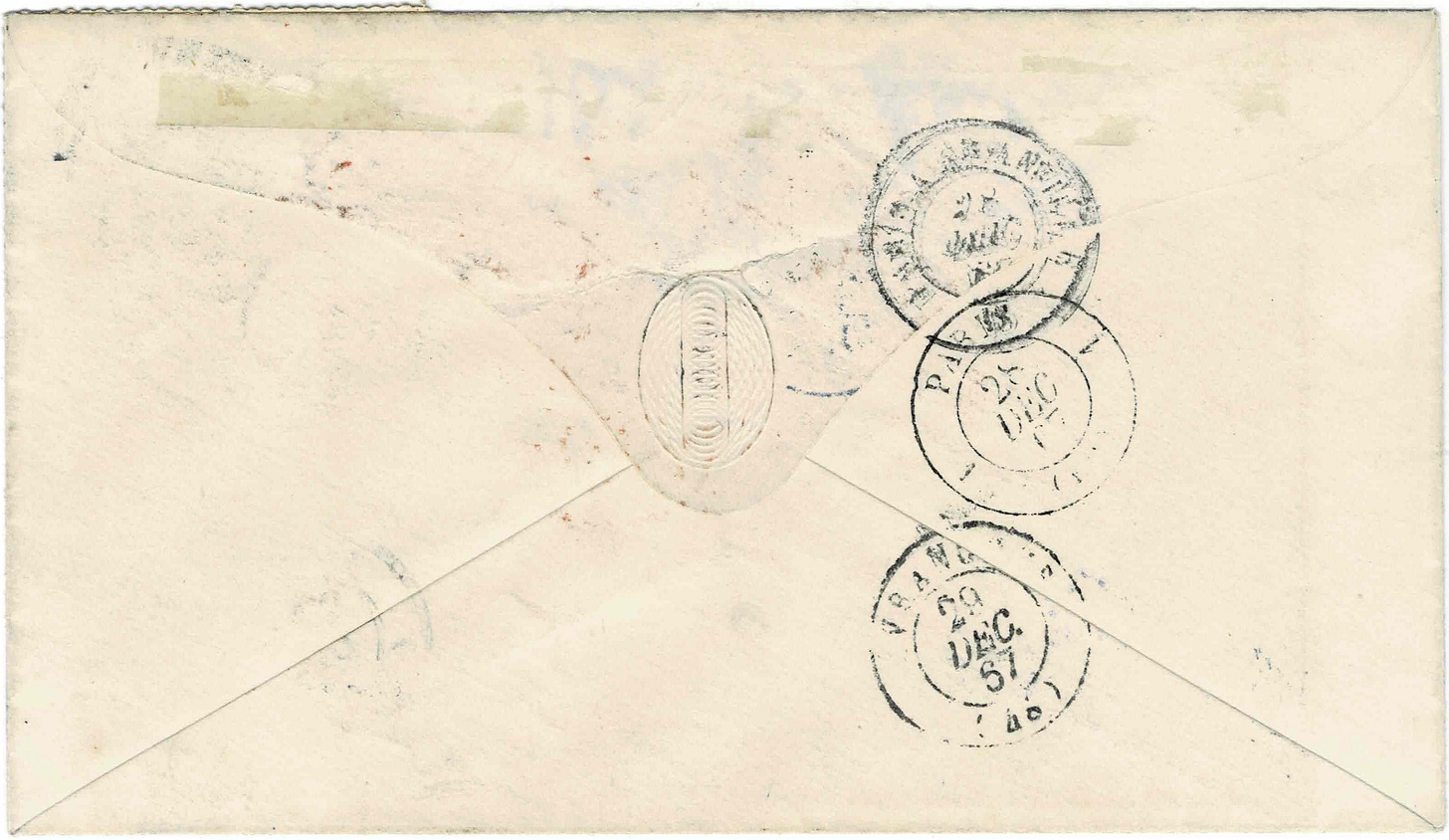

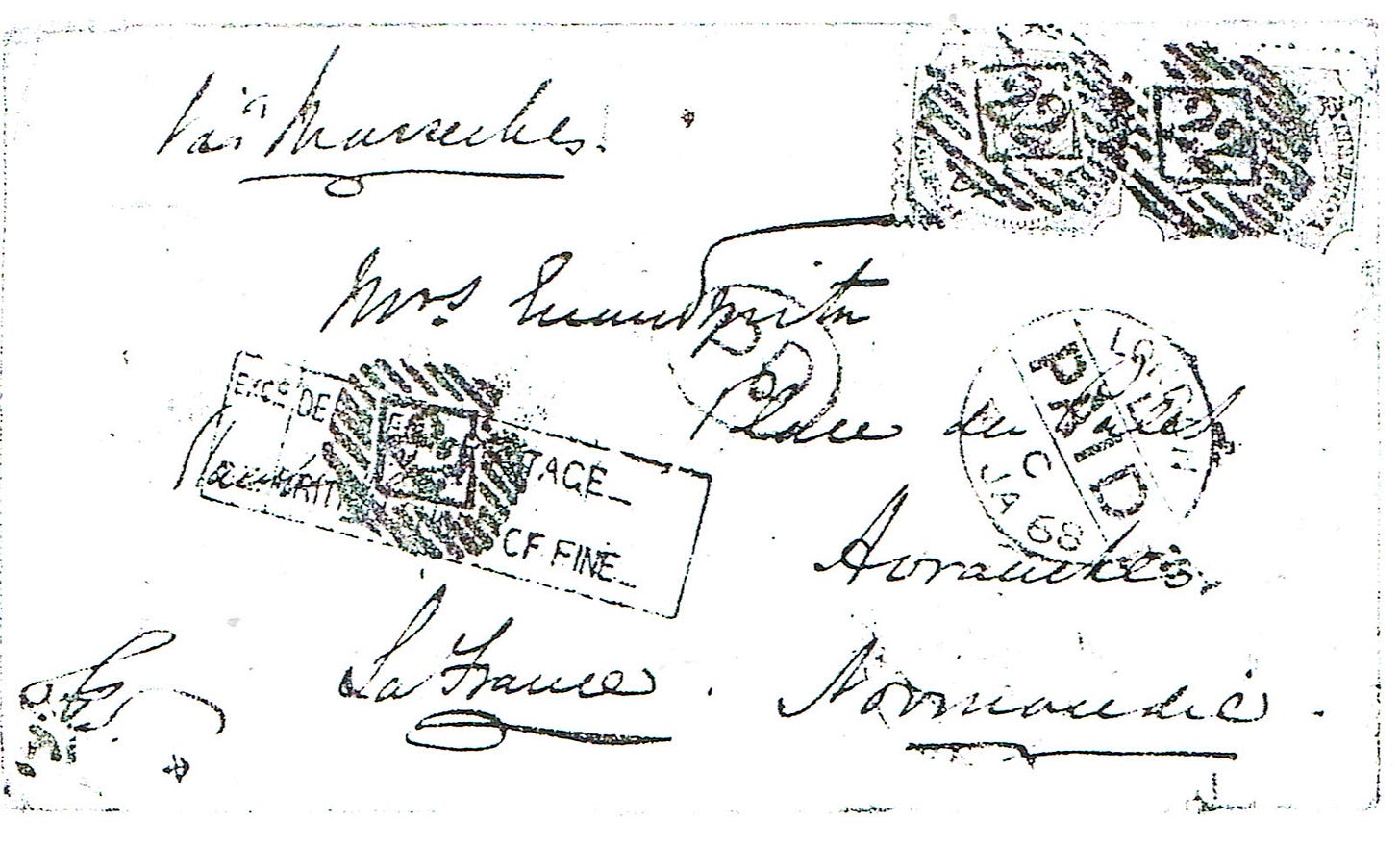

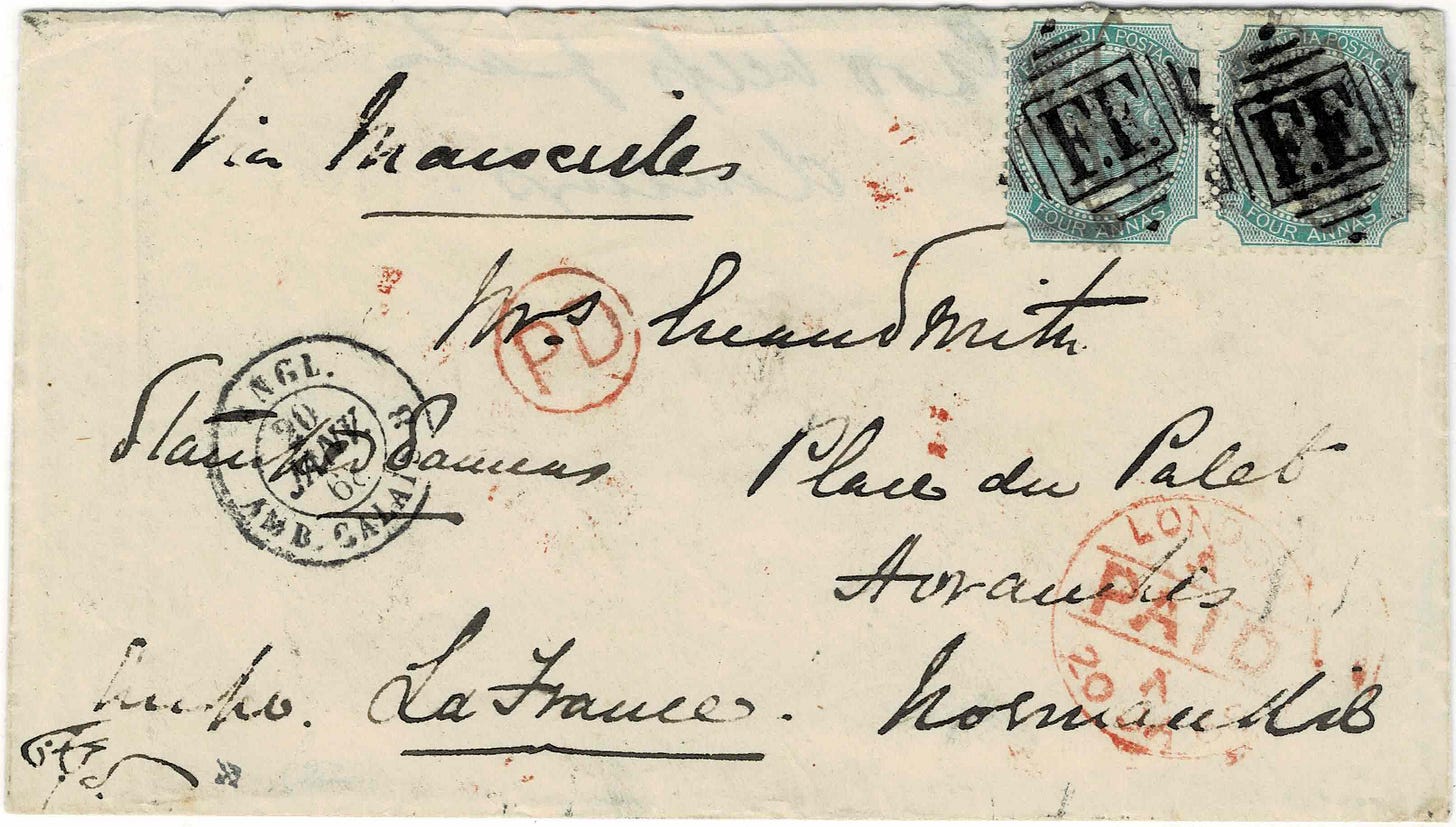

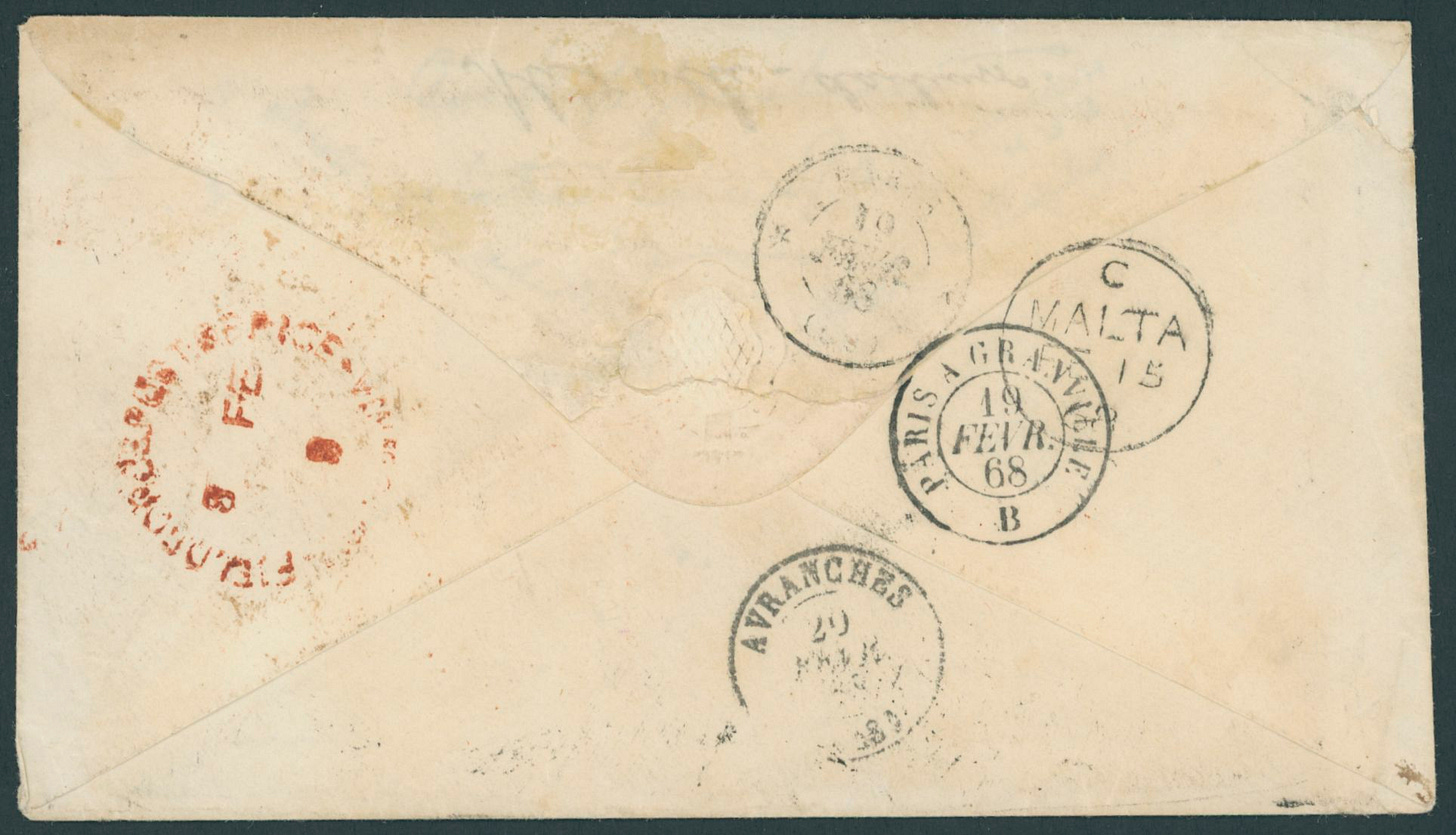

Figure 3 shows the earliest known (and perhaps the prettiest) cover sent from the Expedition by Euan-Smith to his mother, Mrs. Euan-Smith. Note his initials ‘CBS’ bottom left and on the stamps themselves; this was his style! The Abyssinia field force circular datestamp (‘FIELD FORCE POST OFFICE/{Date}/ABYSSINIA’; see Figure 10 for a complete example) and the ‘F.F.’ (Field Force) obliterator (see Figures 8, 9, or 10) reached the place only towards the end of December; hence the stamps were not cancelled at Abyssinia but by the Mediterranean sorters on board P&O steamers.

Going by the Suez datestamp of 16 December, the cover must have posted in the first few days after Euan-Smith reached Zula, i.e. on or after 4 December 1867, so that it could be taken on a despatch boat to intercept the Peninsular & Oriental (P&O) Steam Navigation Company’s packet steamer, cruising from Aden (which place it left 10 December) to Suez, off the volcanic island of Jubbel Teer (today’s Jabal al-Tair) (Figure 4) in the Red Sea.

The interception worked like this: the despatch steamer boat hoisting her ensign at the main by day, or exhibiting three vertical lights at night, and burning a blue light at intervals of 20 or 30 minutes to signal the P&O steamer. However, the despatch steamers often missed the mails and sometimes due to bad weather could not put their bags on board the P&O steamers; or could not receive the bags made up in London or Bombay for the force. When a despatch of the Commander-in-Chief, Sir Robert Napier, ordering the Bengal Cavalry to leave Aden for Abyssinia missed the mail and was detained at Zula for a week, on 6 February 1868 Napier paid put to this arrangement and ordered a weekly service to Suez with and for the English mails and another weekly one to Aden with and for the Bombay mails.7

The Mysterious 8 anna Franking

The cover is stamped 8 annas, which is strange.

The rates applicable on letters from the Expedition, in general, was spelt out in a postal notice issued by A.M. Monteath, Director General of the Post Office of India, dated 16 October 1867 (Figure 5). It said, among other things:8

Letters and other articles posted in Abyssinia for transmission, viâ Aden, by British or French Mail Packets, will be subject to the same conditions and rates of postage as if posted in Aden.

(It is quite likely that when he issued this notice, Monteath did not know the Jubbel Teer arrangement and hence he can be forgiven for thinking that mails from Abyssinia would be sent to either Bombay or Europe via Aden).

The post office at Aden came under the supervision of the post office of Bombay Presidency and stamps of India were used at Aden until 1937. The rates of postage from Aden to France were the same as from mainland India to France.

What was this rate?

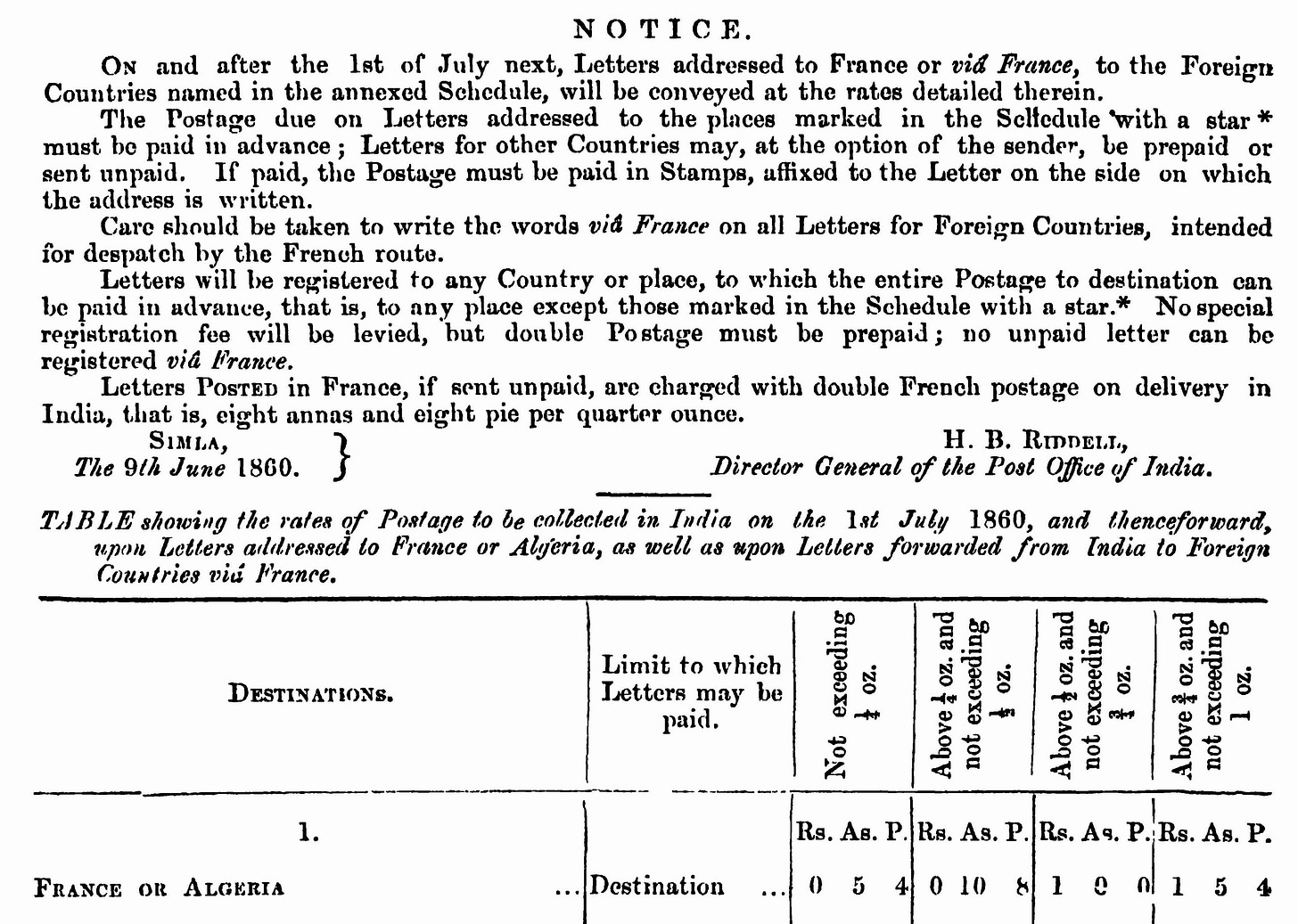

As per a notice (Figure 6) issued by H. B. Riddell, the previous Director General of the Post Office of India, on 9 June 1860, this was 5 annas 4 pies (12 pies = 1 anna) on letters weighing ¼ (quarter) ounce (oz) sent via Marseilles. The rate paid letters to destination and was effective for a fairly long period of time i.e. from 1 July 1860 to when the Marseilles route was abandoned in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian war on 22 October 1870.9

At this time, it is not uncommon to find letters from India overpaid a few pies, generally when stamps of required denominations were not available, especially the 8 pies one. But this cover is overpaid 2 annas 8 pies. Even if the intention was to round off to the nearest anna, the sender should have stamped it a total of 5 annas and not 8.

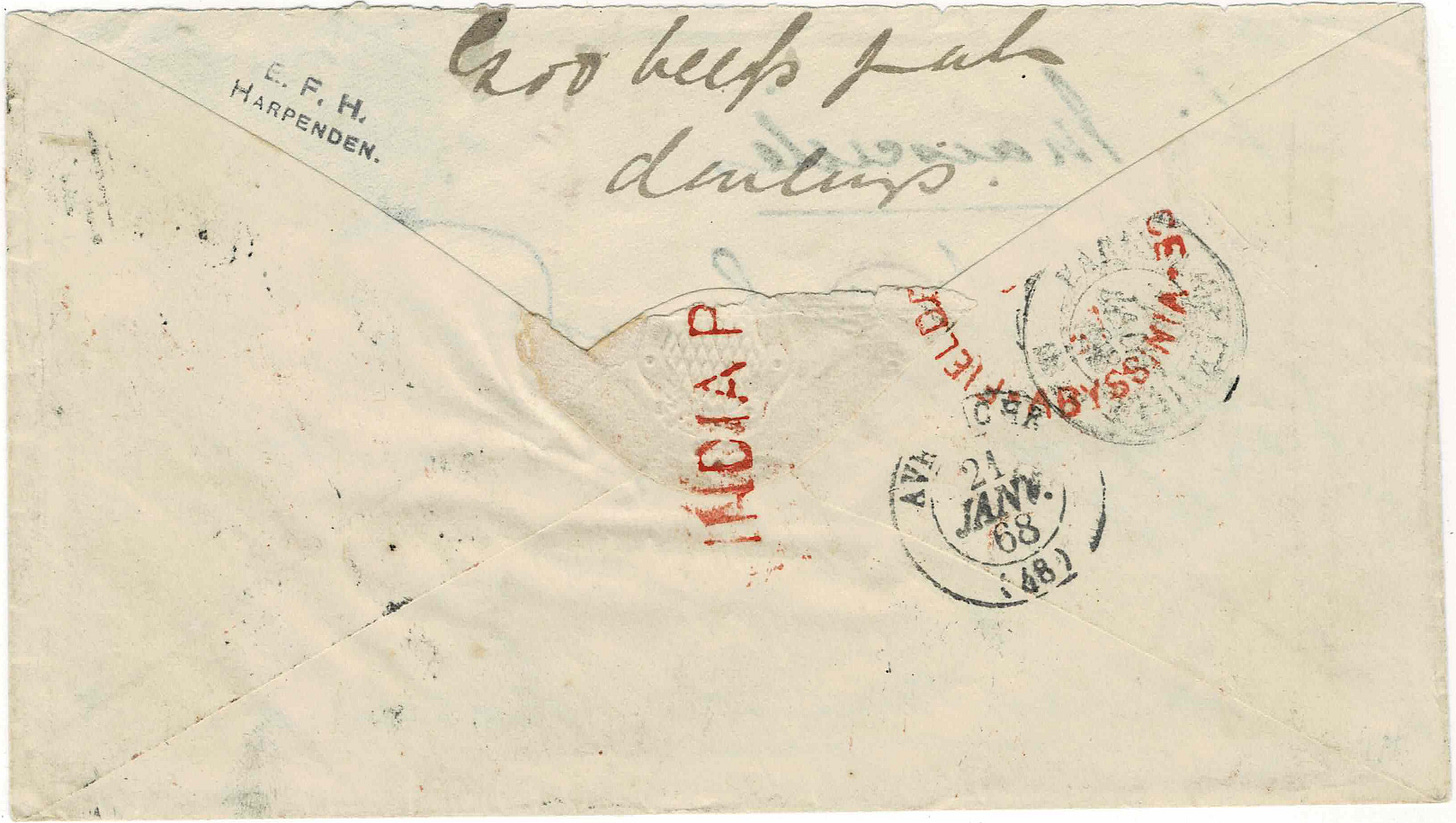

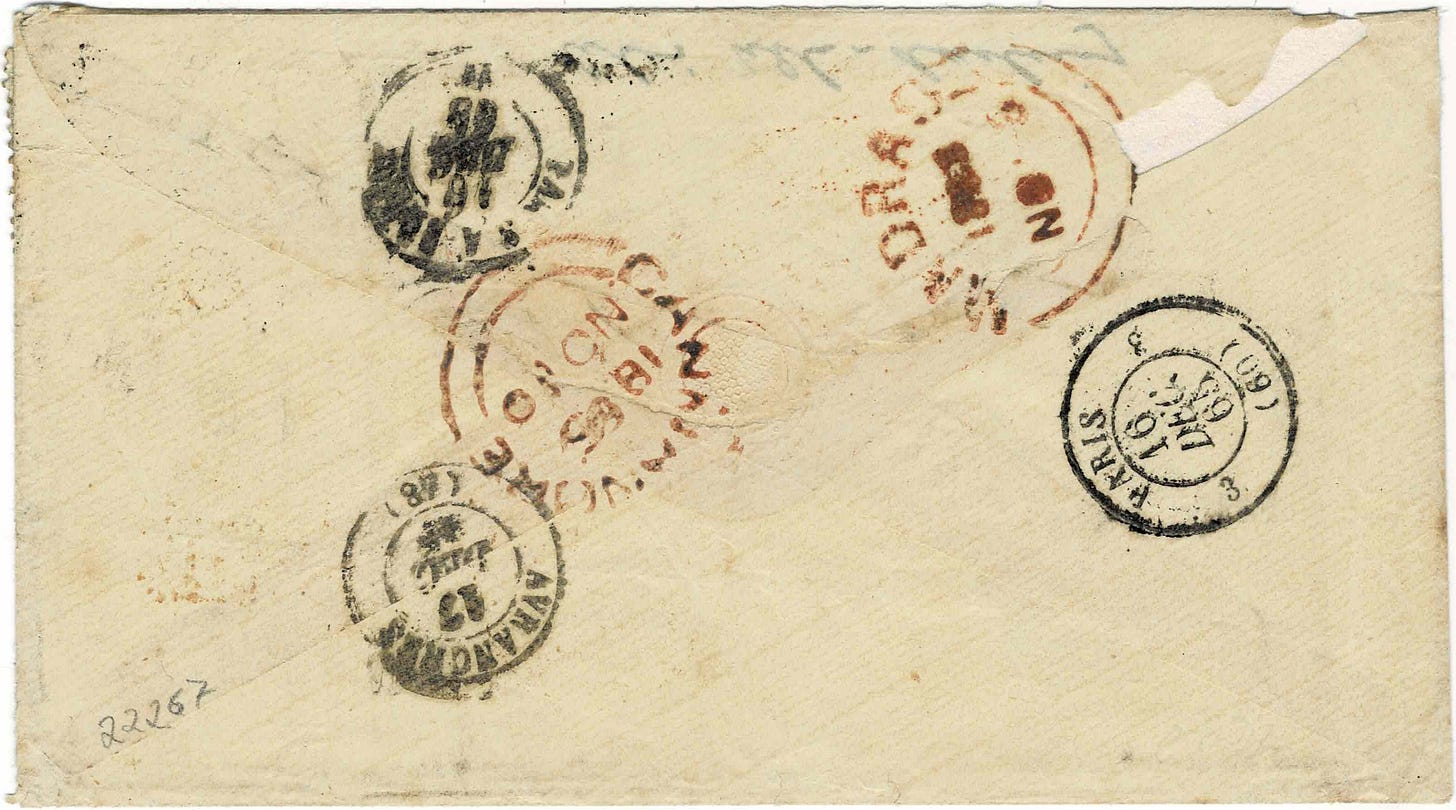

Figures 7, 8, 9, and 10 show further covers from this correspondence. All are stamped 8 annas.

The item in Figure 8 was also considered paid to destination. This is one of two covers from 1867 which shows both the ‘F.F.’ obliterator and the ‘FIELD FORCE POST OFFICE/ABYSSINIA’ datestamp. In addition, it is the earliest with the red ‘INDIA PAID’ (albeit incomplete) handstamp applied in Abyssinia.

The cover in Figure 9 was considered paid only to England. This is the only instance (out of the six) when the ‘GB/40c’ accountancy mark was applied. The ‘GB/40c’ was to let France know that the cover arrived in Britain free of all charges and that only 40 centimes per 30 gm (or 10 centimes or 1 decime or 1d per 7½ gm single) was due to it from France, being British transit charges. On delivery, postage due of 5 decimes (see the French handstamp ‘5’ front centre) or 50 centimes was collected from the recipient being 4 decimes French internal postage plus 1 decime British transit.

So, this begs the point. Why was such a charge not taken for the covers shown in Figures 3, 7 and 8 and which are from an earlier date? Given that only a handful of covers survive, it is difficult to distinguish between ‘standard’ and ‘one-off’ procedures followed at London.

My hypothesis is as follows: On the westward route, almost all covers from the Expedition would have been addressed to places in Great Britain. Hence all mails, irrespective of the address, would be taken to London, at least in the initial months. Even those routed to France via the Marseilles route. When the bags were opened in London, the clerk would have been noticed that the letter pertained to France and required redirection. Since the sender could not be blamed for this kind of convoluted routing with the letter first going to France, onward to GB and then back to France again, no dues were marked at London on covers in Figures 3, 7, and 8. Then, why was the cover in Figure 9 marked as paid only to England and not to destination? Was it because of the lack of the INDIA PAID stamp? Or was it the doing of another clerk who thought differently? I will be interested to hear on this from readers.

The cover in Figure 10 from a month later did not transit London and went directly to France.

The 8 anna Mystery

Why were these covers stamped 8 annas, a rate to France that never existed? The first explanation that would occur in anyone’s mind is that, despite the regulations issued from India, the Expedition post office interpreted and required a different rate to France, perhaps 4 or 8 annas per ¼ oz, instead of the official 5 annas 4 pies. That is, they erred.

But as I have argued elsewhere in the past, postal staff across the world did make mistakes, but they were not common. If postal historians wish to wish away the unexplainable as a ‘error’, it is nothing but taking the easy way out. Further, the postal staff at Abyssinia were drawn from Bombay Presidency and were quite aware of Indian regulations.

There is the other possibility: there being different rules of carriage from Abyssinia to France, and hence different rates. However, I have not found any post office notification which allowed for such a possibility.

The answer struck me when I remembered that lying with me were a couple of unexplained covers from the same correspondence but dating prior to the Expedition.

Old Habits Die Hard!

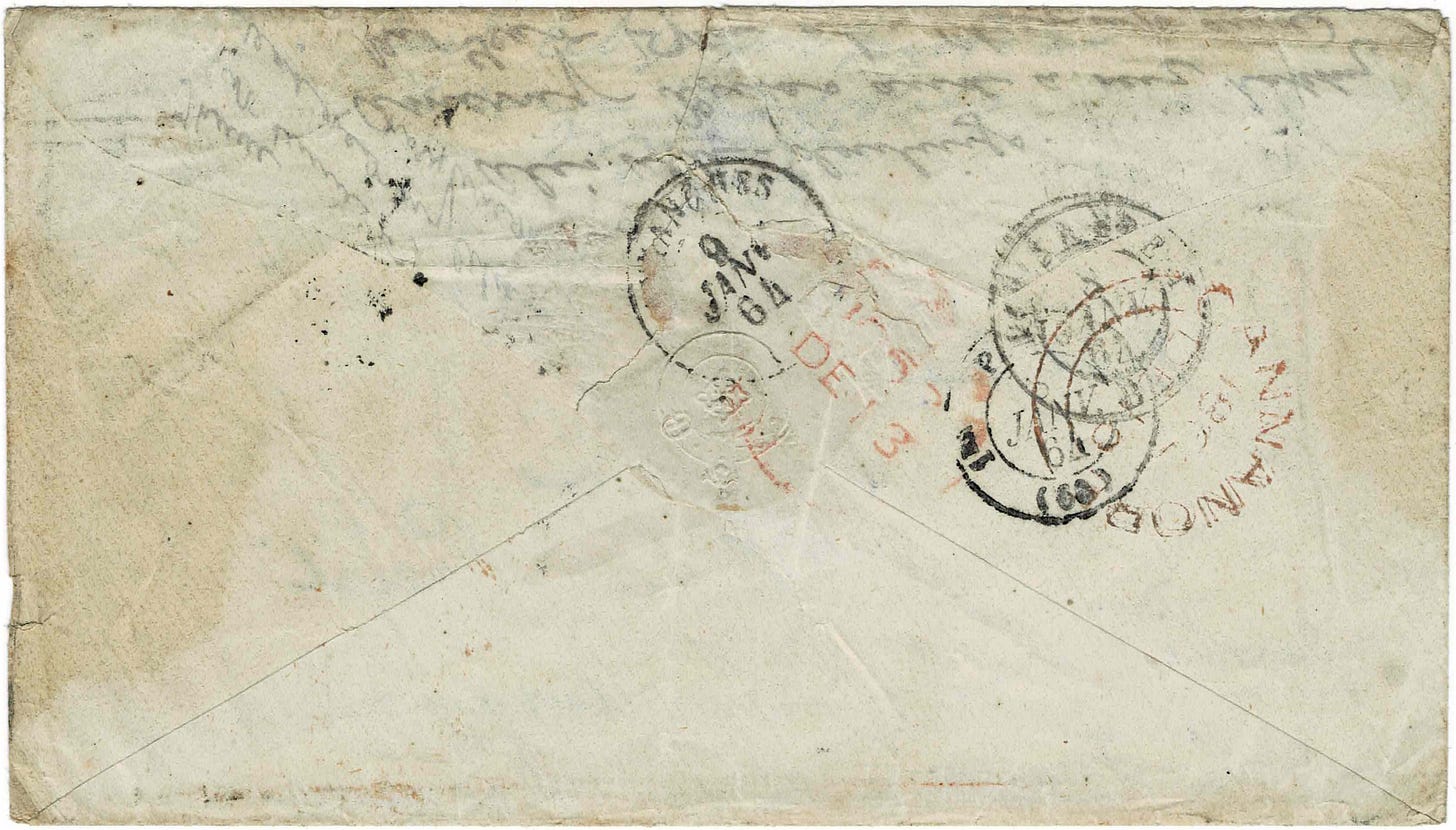

Euan-Smith’s mother, Elisa Bean Euan-Smith, had been living in Avranches in France from sometime in mid-1863 (evidenced basis other existing covers) and Smith presumably wrote to her regularly. Smith was with the 40th Native Infantry of the Madras Army, which was based in Cannanore (now Kannur in the state of Kerala, south-west India) from June 1863 onwards.

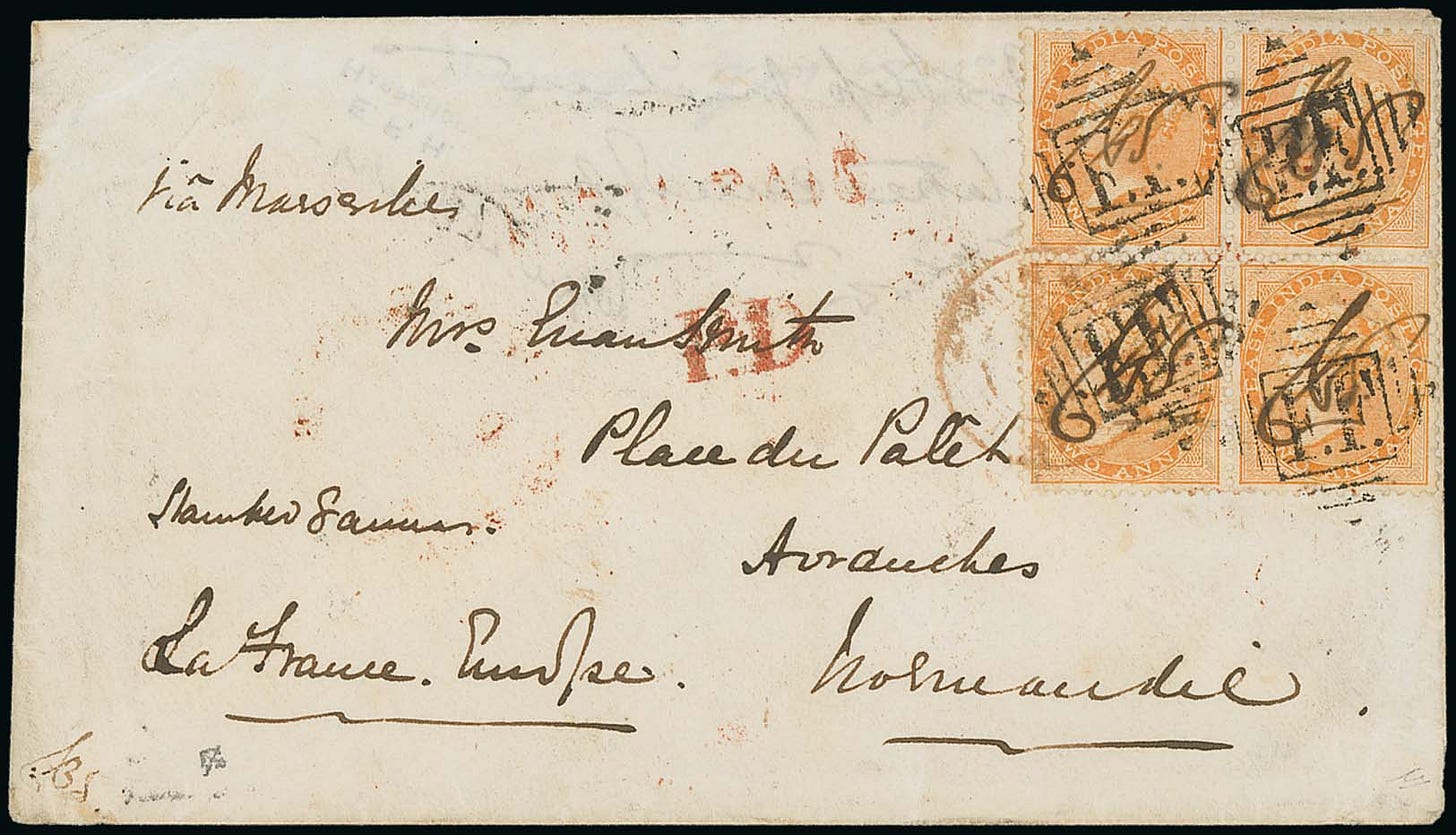

A cover from Cannanore to Avranches datestamped 10 December 1863 is shown as Figure 11. It is franked, what else but 8 annas! This is the first Smith cover that I purchased some years back but was never able to understand why it was overpaid.

Figure 12 shows yet another cover from Cannanore from a couple of years later i.e. 10 November 1865.

There was no question of correspondents not knowing the rates to France from mainland India. I have seldom come across overpaid covers to France in this 10-year period (1860 to 1870) and certainly not overpaid a whopping 50%.

So, the answer to the mystery of 8 annas is kind of anticlimactic. While not a direct proof, the covers from Cannanore provide circumstantial evidence on which a jury would, I believe, hold Euan-Smith guilty of consistently over franking his covers.10 He carried his (bad) habit of sticking extra stamps to Abyssinia.

Why did he do so? My best theory is that he had been paying 8 annas on letters to his mother when she was in Great Britain. It was then the correct rate on mails from India to Britain via Marseilles weighing ¼ to ½ oz.11 And when his mother moved to France in mid-1863, he continued paying the same rate not bothering that the rate to France was lower.

By repeatedly paying extra, Euan-Smith’s covers have certainly puzzled and confounded postal historians over the years and tied them into knots. I hope that this article clears up the confusion surrounding one aspect of the fascinating Abyssinian Expedition and its postal history.

The Sixth Cover

For the sake of completeness, the sixth cover to France is presented as Figure 13. This cover again paid a rate to France which did not exist. The sender probably (and incorrectly) paid double the concessionary Officers’ Letter rate of 6 annas 8 pies via Marseilles for a letter weighing ½ to 1 oz (see note 11 for a discussion on rates). As per rules, Officers’ Letters could be sent to or received from Great Britain only.

Acknowledgements. Luciano Maria for sharing your census of the Expedition and for your thoughts and feedback; I have learnt a lot from you! Akihiko Koiwa for sharing images of the item in Figure 13. Bouquets and brickbats are welcome, especially the latter! Feedback can be sent by email to abbh [at] hotmail.com.

References

Holland, Major Trevenen J., and Hozier, Captain Henry (1870). Record of the Expedition to Abyssinia, Compiled by the Order of the Secretary of State for War, 2 vols, Her Majesty’s War Office, London.

Kaplan, Nachum (1993). “The Napier Expedition, October 1867 – July 1868.” Menelik’s Journal, 9 no. 3, pp. 687-699, [July-September].

———. “The Napier Expedition, October 1867 – July 1868.” Menelik’s Journal, 9 no. 4, pp. 707-711, [October-December].

Kirk, R. (1982). The P&O Lines to the Far East, Vol. 2, Proud-Bailey Co. Ltd., Heathfield, East Sussex, UK.

———. (2003) “The Mediterranean Sea Post Office.” in The British Sea Post Offices in the East., edited by Edward B. Proud, pp.9-130, Proud-Bailey Co. Ltd., Heathfield, East Sussex, UK.

Proud, Edward B. (n.d.) History of the Indian Army Postal Service Volume I 1854-1913. Proud-Bailey Co. Ltd., Heathfield, East Sussex, UK.

Raugh, Harold E., Jr. (2004). The Victorians at War, 1815-1914: An Encyclopaedia of British Military History, ABC-LIO, Inc, Santa Barbara.

Sattin, Gerald (1993). “Abyssinian Expedition, 1868”, India Post, 27, no. 1, whole no. 115, pp.22-23 [January-March].

Sciaky, Roberto (2003). “Postal History of the Napier Expedition.” The London Philatelist, 1306, 173-187 [June].

Wikipedia. “Charles Euan-Smith.” Accessed 29 August 2023. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Euan-Smith

Appendix: Who was Euan-Smith?

Charles Bean Euan-Smith12 (he added Euan to his surname sometime later in life) was the son of Dr Euan McLaurin Smith, of Georgetown, British Guiana and his wife Elisa Bean. Born on 3 September 1842, he was educated privately in England and Belgium. He obtained a commission in the Madras Army as Ensign on 2 March 1859 and became a Lieutenant on 14 April 1861.

Smith served in the 40th Native Infantry of the Madras Army; the 40th were based at Cannanore (more on this place later) from 4 June 1863 until late-1868 or early-1869.13

In the Abyssinian Expedition of 1867-68, Smith was the 'Sub-Assistant Commissaries-General, 1st Class' and was generally responsible for about 500 Madras ‘dhooley bearers’ (porters employed to carry men, especially the wounded, and material). He was part of the ‘advanced force’ and was present at the capture of Magdala, the mountain fortress where the emperor had receded to along with the hostages.

Euan-Smith was promoted as Captain on 30 November 1870. A life of high diplomacy and intense travel followed. He was appointed as secretary to Sir Frederick Goldsmid’s special mission to Persia 1871-72, which was to arbitrate on a border dispute between Persia and Afghanistan. In 1872, he went with Sir Bartle Frere14 as military attaché and private secretary to Zanzibar and assisted in the negotiation of a treaty for the suppression of the slave trade; the treaty was signed in June 1873. He returned to Zanzibar as Counsel-General two years later.

In 1876 he was transferred to the Residency at Hyderabad, which he left for a post as consul at Muscat in August 1879. On 2 March 1879 he was promoted to Major. Shortly after arriving at Muscat, he joined the Second Anglo-Afghan War as chief political officer on the staff of Lieutenant-General Sir Donald Stewart.

Euan-Smith received the beret of Colonel 2 March 1885 and retired 1 March 1889. He was appointed as ‘Her Majesty's Agent and Consul-General’ for Zanzibar in 1887, where he scored some successes. In 1891 he was appointed as ‘Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the Emperor of Morocco’; he tasted failure here and was relieved of his post in 1893. Though appointed to post of ‘Her Majesty's Minister Resident in the Republic of Colombia and also to be Her Majesty's Consul-General in that Republic’ in 1898, he resigned without taking it up.

In his years of service, he was decorated many times. He was awarded the Abyssinian war medal, 1867-68; Companion of the Order of the Star of India in November 1872; Afghanistan war medal, 1878-80; and Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath in November 1890 (Figure 14).

Euan-Smith died on 30 August 1910 of heart failure.

Against an estimate of £2 million, the campaign cost £8.6 million (Raugh 2004, p. 4). Using the website officialdata.org, £8.6 million in 1868 is equivalent to about £1.2 billion in 2023.

Over many years, Luciano Maria of Italy has maintained a record of the Expedition’s postal history and I am thankful to him for having shared his data with me.

At this time, no incoming letter from France to Abyssinia is known to exist.

Further the sixth cover to France, dated April 1868, is franked with two stamps of 6 annas 8 pies i.e. a total of 13 annas 4 pies (Figure 13). Again, this is a strange rate which never existed. The sender probably paid the concessionary ‘officers’ letter’ rate to Great Britain which was 6 annas 8 pies per ½ oz. Note that the concessionary rate on officers’ letters existing 1 January 1868 to 31 December 1869 applied only on letters to and from Great Britain.

The title of this paragraph has been inspired from one of my favourite movies – the 1939 James Stewart starring Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.

Spelt as ‘Zoulla’ in British postal notices of that time and in different ways in different places; I am using ‘Zula’ to be consistent with previous writers. The introduction to M.F.C. Martin’s book English Names for Indian Places: A Coded Index of Indian Post Offices edited by Derek Lang mentions, “Our ancestors in India, when writing eastern place names in western characters, generally got the consonants about right but sprinkled the vowels to taste.” This explains why there are multiple variations in English for the same name.

A report dated 6 February 1868 filed by the correspondent of The Daily News published on 27 February 1868 says “…the whole arrangement been condemned this morning (emphasis the author’s) by Sir R. Napier, who, in consultation with Captain Holland, the indefatigable assistant-quartermaster-general substituted the one service which alone can be efficient-viz., a weekly steamer to Suez with and for the English mails, and to Aden with and for the Bengal mails.” Meanwhile, Proud (Vol. I, p. 41) mentions that the last sailing to Zula took place on 30 January 1868. The next question would be the days on which the weekly steamers sailed from Zula. Holland (1870, Vol. II, p. 153) that mails were sent from Zula every Saturday for Suez, and on every Tuesday for Bombay. On the other hand, The Bombay Gazette of 4 April 1868 carries a report dated 17 March 1868 filed by their own special correspondent which mentions that steamers left Zula for Suez every Friday morning and for Aden every Monday morning and that mails were made up at Zula the previous night. This effectively means that one should not get too bogged down trying to figure dates of sailing from Zula since they can always differ by a day or two.

Paragraph 1 concerns itself with mails from India to the Expedition. The rate charged on such mails was 4 annas i.e. the same as to Aden. The words in paragraph 2 makes it amply clear that it applied to outgoing letters from Abyssinia to anywhere in the world, whether Great Britain or India, or any other place; not just from Abyssinia to India. Why? Well, I have not seen any subsequent postal notice issued by the Indian post office on this subject. Hence, if we are to assume that this particular paragraph only pertained to postage rates between Abyssinia and India, some rhetorical questions will be in order! What gave authority for rates between Abyssinia and elsewhere? Why do we see standard Indian rates such as 6 annas 8 pies or 8 annas 8 pies (rates to Britain via Marseilles) or 4 annas (rates between India and Abyssinia as well as rate to Britain via Southampton) on letters from the Expedition?

To be precise, post 22 October 1870, the rate of 5 annas 4 pies continued for some more years but only if letters were sent by French packets, or (later) via the French post office in Alexandria. However, such usages are scarce.

While I have shown only two covers, many more exist written from various places in South India to Normandie, all stamped 8 annas.

The postage rate on letters from India to Great Britain via Marseilles was 6 annas and 8 annas on letters weighing up to ¼ oz and between ¼ and ½ oz respectively. This rate prevailed between 29 January 1857 and 31 May 1863. The rate was reduced to 6 annas 8 pies per ½ oz from 1 June 1863 until 31 March 1868. And increased to 8 annas 8 pies from 1 April 1868 until the Marseilles route was abandoned on 22 October 1870, on the basis of a telegram received by the Indian post office from HM Post Master General dated 19 October 1870. Further, there existed a concessionary ‘Officers’ Letter’ rate between 1 January 1868 to 31 December 1869. As far as this Expedition is concerted, such letters paid, between 1 April 1868 to the end of the Expedition in June 1868, a rate of 6 annas 8 pies and 4 annas per ½ oz via Marseilles and Southampton respectively, a concession of 2 annas each.

Much of the information in this section has been drawn from Smith obituary in The Army and Navy Gazette of 3 September 1910 and The Railway News of the same date.

The 40th arrived at Saugor on 14 January 1869. Dates from The India Office and Civil Service List of January 1868 and July 1869.

Philatelists will recognize him as the person who in 1852 introduced Asia’s first stamps – the Scinde Dawks – when he was Commissioner of Sind.