This article was first published as “Madras Presidency Outgoing Mails″ in India Post 57 no. 2 whole no. 227 (April - June 2023). India Post is the journal of the India Study Circle for Philately.

In 1793, the East India Company’s (‘EIC’) Board of Directors decided to levy packet/ship postage1 on all letters and packages beyond the weight of two ounces (‘2 oz’); this was communicated to the three Presidencies of Bengal, Madras, and Bombay by a letter dated 5 June 1793.

In my earlier article,2 I wrote about this rule and its implementation in the Bengal Presidency. In this piece, I will cover the postal history of the 2 oz period from the perspective of the Madras Presidency and its post office (‘PO’ hereon). Nothing has been written on this subject so far. One reason could be that Madras didn’t introduce any ship despatch handstamp3 such as the one that Bengal did, the Giles SD1; therefore, letters from Madras from this period wouldn’t have captured the attention of collectors. The other reason may be that letters from this period are scarcer than those from Bengal.

I would like to mention just as no letters from Bengal weighing more than two oz are known, so are none from Madras.

Implementing Order

On 7 December 1793, the said direction of the EIC’s Board (‘2 oz rule’ hereon) was implemented in Madras (Figure 1) by an advertisement published by order of the Governor in Council4 under the hand of Robert Clerk, Secretary to the Government. On 21 January 1794, the scrupulous Postmaster General of the Madras GPO, William Jones, even published a notice giving a list of detained letters weighing more than two oz which wouldn’t be forwarded unless the ‘tax’ was paid.5

Letters from Madras Presidency 1793-95

Almost all letters emanating from the Madras Presidency during this two-year period that I am aware of (counting in single digits) are those from the correspondence of Thomas Fiott de Havilland (‘de Havilland’ hereon) who was then an Ensign with the Madras Army’s Engineer Corps. In a long and distinguished career, he served in India from 1792 to 1822 (save some years in between when he was at home on the island of Guernsey, Great Britain) going on to become the Acting Chief Engineer of Madras Presidency and retiring as a Lieutenant-Colonel in 1825.

Letter #1

Figure 2 shows one such letter in its entirety. It comprises 57 numbered sides and was written by de Havilland over a period of more than eight months: starting 25 February at Madras and closing 7 October 1794 at Trichinopoly!

There are many interesting historical aspects to this letter; however, I will concern myself only with postal history. In his postscript, de Havilland writes:

My Letter is so long that I must make two parcels of it, as it weighs more than two ounces; if I were to make only one it would cost me 10 Sh: if in two it is only a few pence. The first will be No. 1st and the last No. 2d.

The postscript makes it clear that de Havilland (and surely the public as well) was aware the 2 oz rule and the need to keep his letters under than weight to avoid the onerous costs.

This letter must have weighed more than two and less than or equal to three oz and would have been chargeable with Rupees (Rs) 4. At the then exchange rate of 1 M(adras) Rupee (Rs) equalling 2s3d (see the November-December 1794 letter discussed later), Rs 4 works out to 9s (and not 10s, perhaps a mistake on de Havilland’s part).

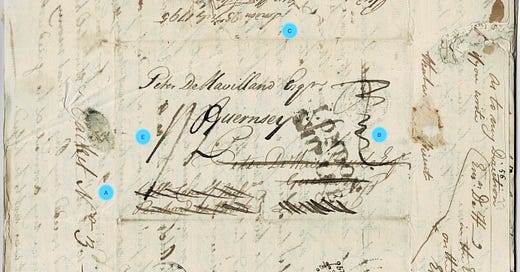

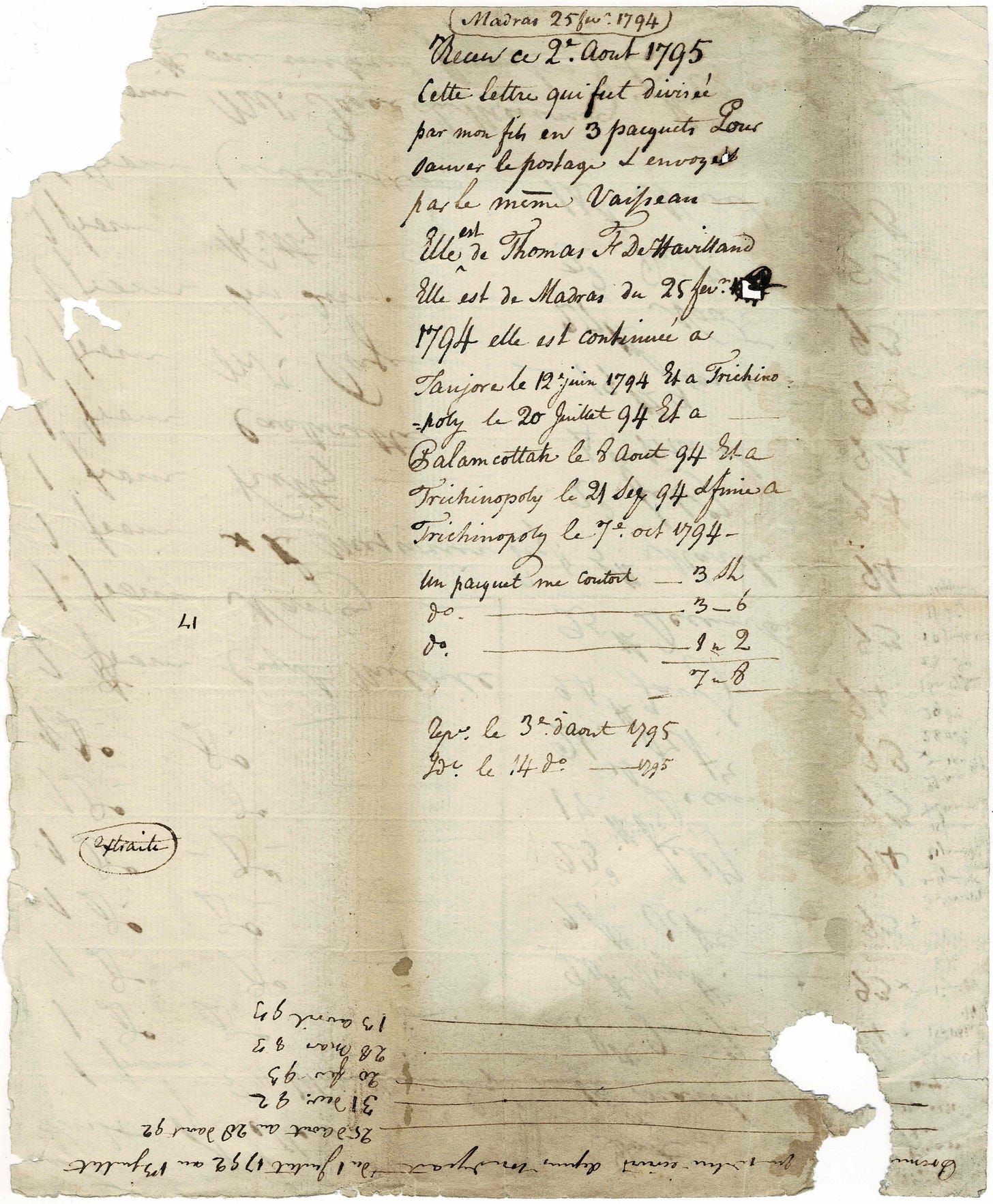

In the end, de Havilland had to make three packets of his long letter; on the left side panel, one can see the words ‘Packet No. 3’. Further, when the recipient, his father Peter de Havilland, received the letter, he wrote and enclosed a small note in French which when translated reads (Figure 3):

This letter was arranged by my son in 3 packets to save postage and send by the same ship It is from Thomas F de Havilland It is from Madras on 25 feby. 1794 It was continued at Tanjore on the 12 June 1794 and at Trichinopoly on the 20th July 94 and at Palamcottah on the 8th August 94 and at Trichinopoly on the 21 Sept. 94 and finished at Trichinopoly on the 7th Oct. 1794 One packet cost me-------3 sh. Do-----------------------3-6 Do-----------------------1-2 —— 7-8 —— Received the 3rd August 1795 Answered the 14th do. 1795

The three letters were sewn together on receipt. Unfortunately, the wrappers of the first two letters, which were charged 3s and 3s6d, were discarded during the process; only the one of the third, which was charged 1s2d, was saved.

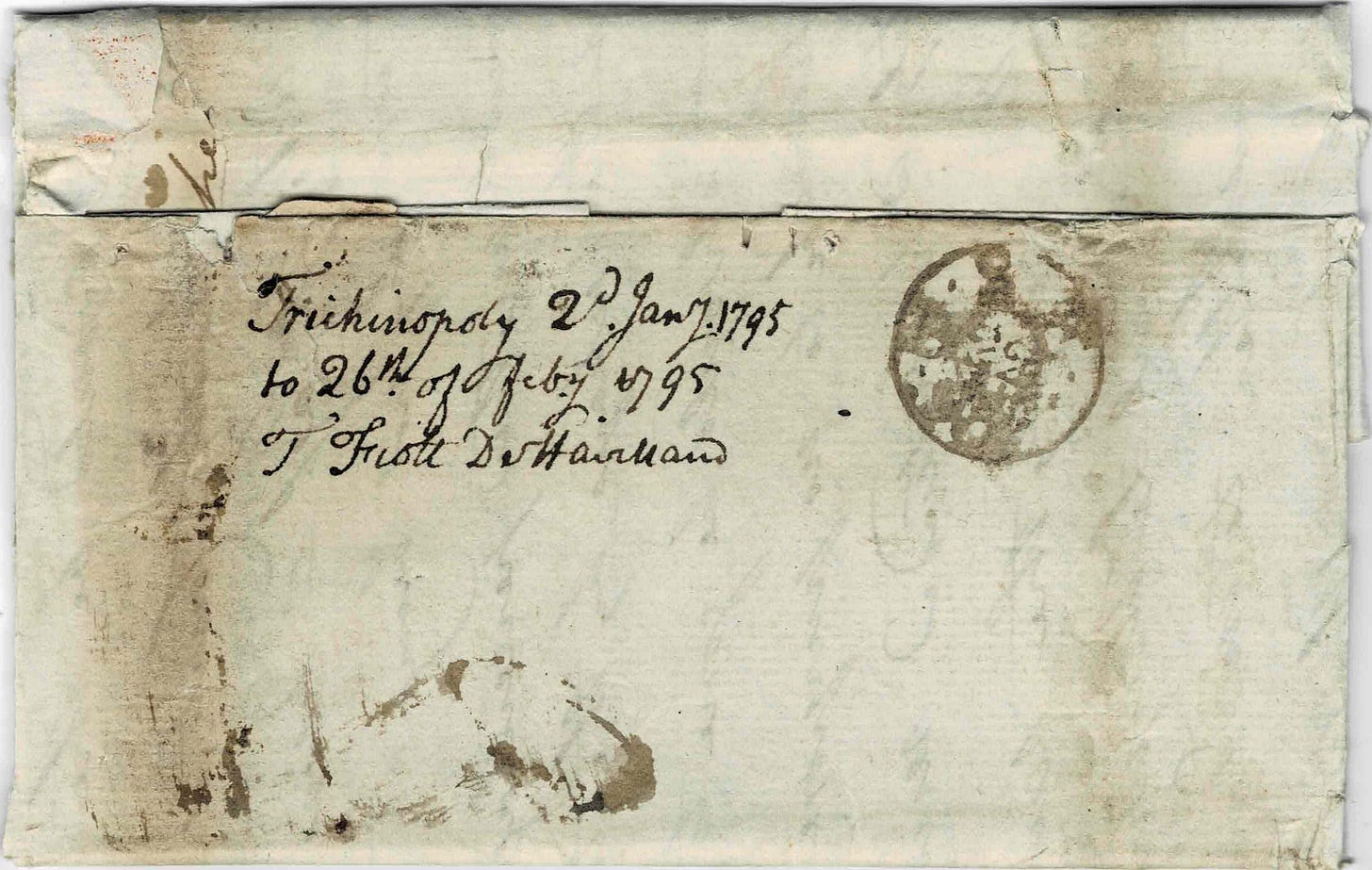

Letter #2

In another letter (Figure 4) written on various dates between 2 January and 26 February 1795, de Havilland writes:

Inclosed I send Nancy a few lines, which makes this come to about 2 Ounces. I must therefore conclude & dispatch it as soon as possible.

Once again, one notices that de Havilland was conscious of the need to keep his letters under 2 oz.

Agents/Friends at Madras

The Bengal Presidency order dated 4 December 1793 issued by E. Hay, Secretary to the government, mentioned that the Honourable Court of Directors had “directed that a Person belonging to the Secretary’s Office, being a Covenanted Servant,” be “appointed to carry the new regulations into execution.” Consequently, Bengal appointed one Mr. Richard Ahmuty, “by whom alone Letters or Packages, to be transmitted in future to Europe in the Government Packets” would be received.

Further, the order mentioned that writers situated “at a distance from Calcutta should instruct their Agents or Friends at the Presidency to cause their letters to be delivered to Mr. Richard Ahmuty, instead of sending them, as has frequently happened, under cover to the Secretary, or the Gentlemen in his Office, for transmission by the Packets”. In order words, such writers had to send their letters under cover to their Agents or Friends at Calcutta and not directly to Ahmuty.

The direction of the Court of Directors applied to all Presidencies. It is quite likely that the Madras government too would have appointed an authorised person through whom all outgoing letters had to pass before they could be put aboard the EIC ships. And it is also probable that writers from outstation locations would have had to send their letters to their agents or friends at Madras so that the latter could deliver them to such authorised person.

Unfortunately, the relevant Madras government order hasn’t been found. However, de Havilland confirms this arrangement in one other letter dated 28 November to 28 December 1794.6

But what is still a greater Hardship is that unless you have a person to inclose them to at Madras you cannot write Home for they will take no Letter for Europe unless they are forwarded to a friend at Madras.

In this context, the word ‘inclose’ means enclosing letter(s) inside another cover; in postal history parlance, this practice is referred to sending letters ‘under cover’.

De Havilland’s ‘friend’ or rather, forwarding agent, was the merchant and financier, John Hunter.7 In yet another letter dated 24 March 1795, de Havilland writes:

I enclosed my last Despatches on the 26th Ultimo, & sent them to Madras for the last fleet of Indiamen which sail on the 6th instt. But am not certain whether they have been forwarded to you as Mr. Hunter has not written me since.

Carriage to Madras: via the PO or privately?

In the aforesaid November-December 1794 letter, de Havilland talks about the 2 oz rule as well as inland rates of postage.8

…the letters we send to Europe are charged very differently. – When you put them at the office if they weigh 2 Ounces (under that only one fanm.) you pay 4 Rupees (9 sh:) if 3 ounces, 9 Rupees &c. in proportion of the Square of the Number of ounces so that if a Letter weighed 1 Lb. you must pay 16 times 16 Rupees which is 28 £Stg. 16 sh: - Besides this, there is the Postage from whatever station you are, also Madras, which is the same Rate as any other Letter, 1 fanm. p. 100 M. for a single Letter 2 fans. for a double & so forth. –

(Madras Currency: 80 cash = 1 fanam and 12 fanams = 1 Madras Rupee. British Currency: 12 pence (d) = 1 shilling (s) and 20 shillings = 1 Pound (£ or stg.)

Since de Havilland mentions inland postage rates to Madras, it appears that he was, more likely than not, using the post office to send his letter(s) under cover to Madras, and not a servant or friend.9 And if was indeed doing so, he would have also been paying the inland postage on such covers from Trichinopoly to Madras. The distance between the two stations was between 200 and 300 miles10 and hence the postage, at the rate of 1 fanam per 100 miles, was 3 fanams single. Single was defined as letters weighing up to 2½ Rupees, double as those weighing 2½ to 3½ Rupees, treble 3½ to 4½ Rupees, and so on.11

This combination of (a) sending letter(s) under cover and (b) the likelihood of paying inland postage on such covers implies that one wouldn’t find any town handstamps (which were anyway hardly applied during this early period) or manuscript postage marks on the enclosed letters; any such would have been on the covers themselves which would have been discarded by the agent on receipt.

End of the 2 oz Rule

In 1795, “on account of the Inconvenience” which individuals had sustained, the EIC Board decided to abolish the 2 oz rule. Their letter of 6 May 1795 was published as an order dated 5 September 1795 under the hand of J. Webbe, Secretary to the Madras government (Figure 5).

Acknowledgements

Max Smith and Martin Hosselmann for their valuable inputs. Feedback is always welcome; my email id is abbh [at] hotmail.com.

Max Smith calls this levy the ‘Company’s packet rate’. One reason for not calling it ‘ship postage’ is that it was imposed by London and not by the respective Presidency’s government. On the other hand, the term ‘ship postage’ is also arguably right since the EIC ships were not ‘packets’ in the sense generally understood by postal historians i.e. vessels contracted by the government to carry mails on a regular basis.

Bhuwalka, Abhishek. “India’s First Ship Despatch Handstamp.” India Post 57 no. 1 whole number 226 (January-March 2023): 53-56.

In fact, Madras didn’t introduce a ship dispatch handstamp until 1815!

Then Sir Charles Oakeley (1751-1826) who was Governor of Madras from 1790-94.

A copy of this can be seen in my aforementioned article.

Transcripts of many of the early de Havilland letters are available on the India Study Circle’s website under ‘The Carter Papers’.

John Hunter worked at the Carnatic Bank before he started his own financing company on 4 June 1792. By 1798 he was joined by George Hay. The firm was dissolved in 1817 on the death of Hunter.

This paragraph helps us know the then prevailing exchange rate which was 1 Rs equalling 2s3d.

There are a couple of arguments that one can make against the private carriage of de Havilland letters to Madras. First, Trichinopoly was a reasonably big town and would have had a postal establishment for ensuring regular communications with Madras. Second, consider the period. It would take many days of travel to reach Madras and sending a servant with letters would have been many times more expensive than the PO. Further, it would be some coincidence if de Havilland managed to find friends going to Madras around the same time as the EIC’s ships came calling.

The Madras Almanac of 1800 gives the distance between the two towns as 207 miles. However, a cover from July 1788 from Trichinopoly exists with the manuscript postage marking ‘pt. pd. 4f’ or postage paid 4 fanams. This was either because the distance was then assessed as 300-400 miles (blame it on Tipoo Sultan for making the postal route circuitous?) or a yet unknown outgoing ship postage rate of one fanam.

These weigh scales, modelled initially on those prevailing in Bengal, were in force from 1 June 1786 to (likely) 31 December 1798.