This article was first published as “India Officers’ Letters, 1868-69″ in India Post 55 no. 1 whole no. 218 (January - March 2021). India Post is the journal of the India Study Circle for Philately.

I intended to add an appendix covering letters from the fascinating Abyssinian Expedition of 1867-68. However, the appendix started rivaling the main piece in size and stature! Therefore, it will be presented as a standalone article in the near future.

Sometime in 2010, I chanced upon a few Officers’ letters on Stanley Gibbons’ online shop. The description of those covers mentioned that there existed a concessionary rate of 6a8p via Marseilles instead of the normal rate of 8a8p (annas is abbreviated ‘a’ and pies ‘p’; the currency was 12 pies = 1 anna and 16 annas = 1 Rupee; also 1a = 1.5d) and that it was valid for a very short while from 1 April 1868 to 31 December 1869. Being the greenhorn that I was, I wondered how Stanley Gibbons knew these dates so precisely! More importantly, these short-lived letters intrigued me.

Even after having collected them for some time now, I did not know how interesting they could be until I started looking into them for preparing an online ‘short’ presentation for the 8th India Study Circle Zoom meeting on 15 August 2020. This article is a result of those researches.

Background

Privileged1 postage rates have been often given to soldiers and officers of the military forces from time to time. In Great Britain, soldiers and seamen as well as non-commissioned officers were first given access to a concessional rate of postage of 1d per single letter2 in 1795.3 This privilege was extended to the same category of persons employed by the East India Company in 1815.4 Officers i.e., commissioned and warrant officers, enjoyed such privileges, though at a rate higher than the 1d one, during the Crimean War and they were abolished once the war ended in 1856.5 However, seamen and soldiers including those in the service of the East India Company continued to enjoy the 1d rate.6 This article aims to cover the privileged rates applicable to officers (but not soldiers) for sending and receiving mails from and to Great Britain.

The very next year, it was decided that, with effect from 1 June 1857 (Figure 1)7

…on every letter not exceeding half an ounce in weight, posted in or addressed to any part of the United Kingdom, and sent from or to any Commissioned Officer (whether in the Navy or the Royal Marines), or any Warrant Officer, Midshipman, or Master's Mate, employed in any of Her Majesty's ships or vessels on any foreign or colonial station, and transmitted by the post between any place in the United Kingdom and any such ships or vessels, direct or through any colony or foreign country, there shall be charged and taken, in lieu of any rates of postage now payable by law on such letters, an uniform British rate of six pence.

On second glance, this was not really a concession as it was made out to be since steam postage from and to the Great Britain and most of its colonies was already at 6d. Further, this facility was available to officers “serving on board any of Her Majesty’s Ships on a Foreign or Colonial Station”.8 However, to secure this privilege, such letters were to be sent in bags made up on board the ship and only British stamps could be used for prepayment of such letters.9 Hence Martin & Blair (pg. 19)10 point out that even if the mails were sent from an Indian port, they cannot be construed to be ‘Indian’. Most curiously, this privilege was not extended to officers associated with the army. This had to wait for a decade.

Introduction of Officers’ Rates

In 1867, the British authorities decided to introduce privilege rates for the army’s officers (Figure 2) serving ‘in any of Her Majesty’s colonies’ with effect from 1 January 1868 whereby:

…on every letter not exceeding half an ounce in weight, posted in or addressed to any part of the United Kingdom, and sent to or by any commissioned officer in the army whilst actually employed in Her Majesty's service, in any of Her Majesty's colonies, and transmitted by the post between any place in the United Kingdom and any such colony direct or through any Other colony, or any foreign country, there shall be charged and taken in lieu of any rates of postage now payable by law on such letters, an uniform rate of postage (British and colonial combined) of sixpence.

Given the British Treasury Warrant and its publication in The Gazette of India, the Indian post office had to ensure that they were in line with these instructions.11 Accordingly, the India Office in London informed the Indian government of this direction on 8 November 1867 and the same was notified on 30 December 1867.12

Rules Applicable to ‘Indian’ Officers’ Letters

Since these reduced postage rates were a privilege, the attendant privilege came with certain terms and conditions.

Eligible Classes

At first only commissioned officers in the army actually employed in Her Majesty's service were entitled to this facility; military officers in civil employ13 as well as officers on leave could not. Commissioned officers could be serving in a regiment, corps, or detachment or could belong to a department within the army. A few months later, in May 1868,14 the British government added superintending and first-class schoolmasters15 to list. This was duly notified by the Indian post office on 5 August; the notification included warrant officers.16

Country

Officers’ Letters could only be addressed to or received from Great Britain at the concessionary rates.

Superscription

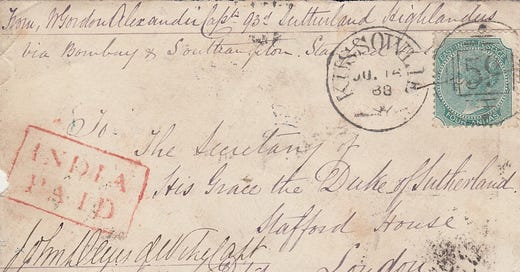

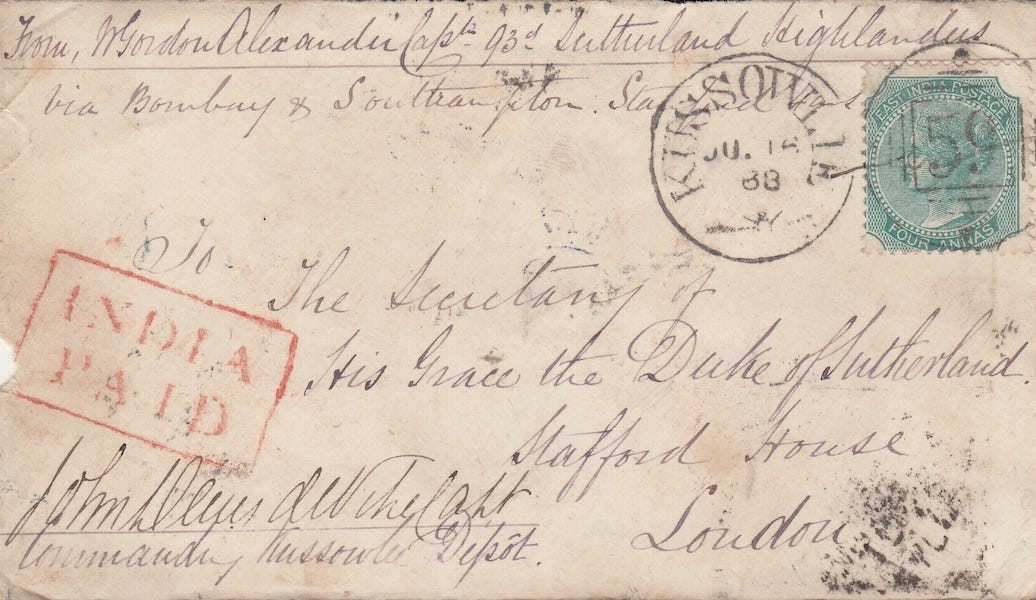

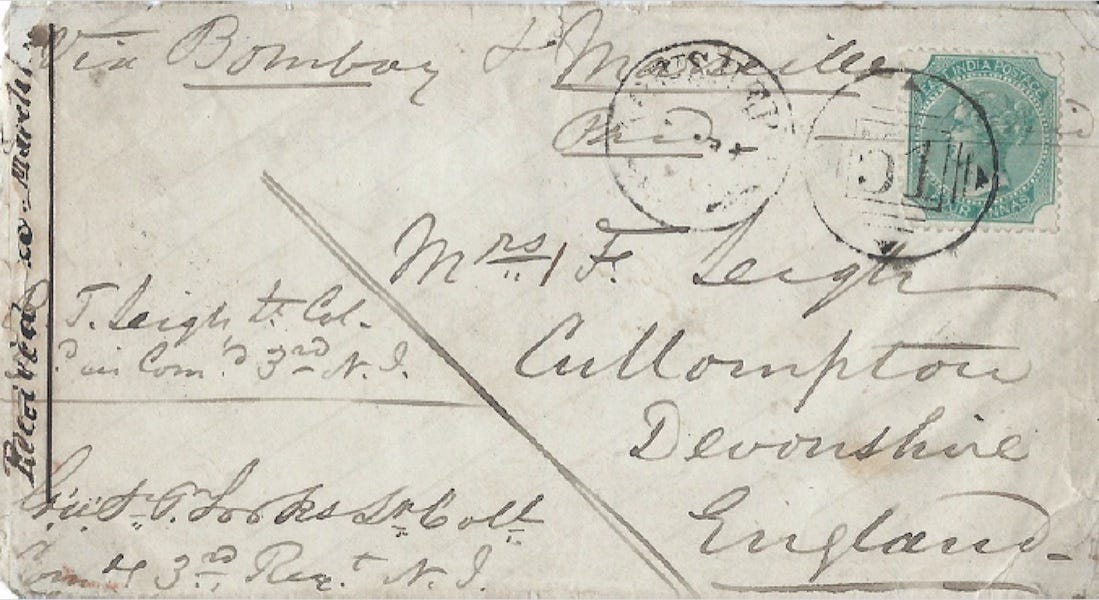

For letters posted in India, the letter needed to be: (Figure 3)

Signed by the Officer sending the letter

Signed by the Commanding Officer of the Regiment, Corps, or Detachment in which the sender was serving, or the local head of the Department to which he belonged, and the name of such Regiment, etc.

Of course, the route through which the sender wished to send the letter (via Southampton or Marseilles) would also need to be superscripted as in the normal case for all overland letters

In case the letter was being sent by a Commanding Officer or Head of a Department, it was later recommended that he sign it twice – once as the sender and once again (cross-ways) as the Commanding Officer, “…so as to leave nothing to conjecture.” (Figure 4)17

Similarly, for letters received in India, the letter needed to be:

Addressed to the Eligible Officer

As superscription, bear the rank of the addressee and his regiment, corps, or detachment

French Packets from Calcutta and Madras

Letters sent by French packets were not entitled to any privilege rates.18 Apart from the P&O, French steamers called at Calcutta and Madras (but not Bombay) and could carry Indian mail via the overland route; sometimes they could get letters to their addresses quicker. This is not to be confused with the ‘Via Marseilles route’ which could be taken by either British or French packets.

Rates Applicable to Officers’ Letters

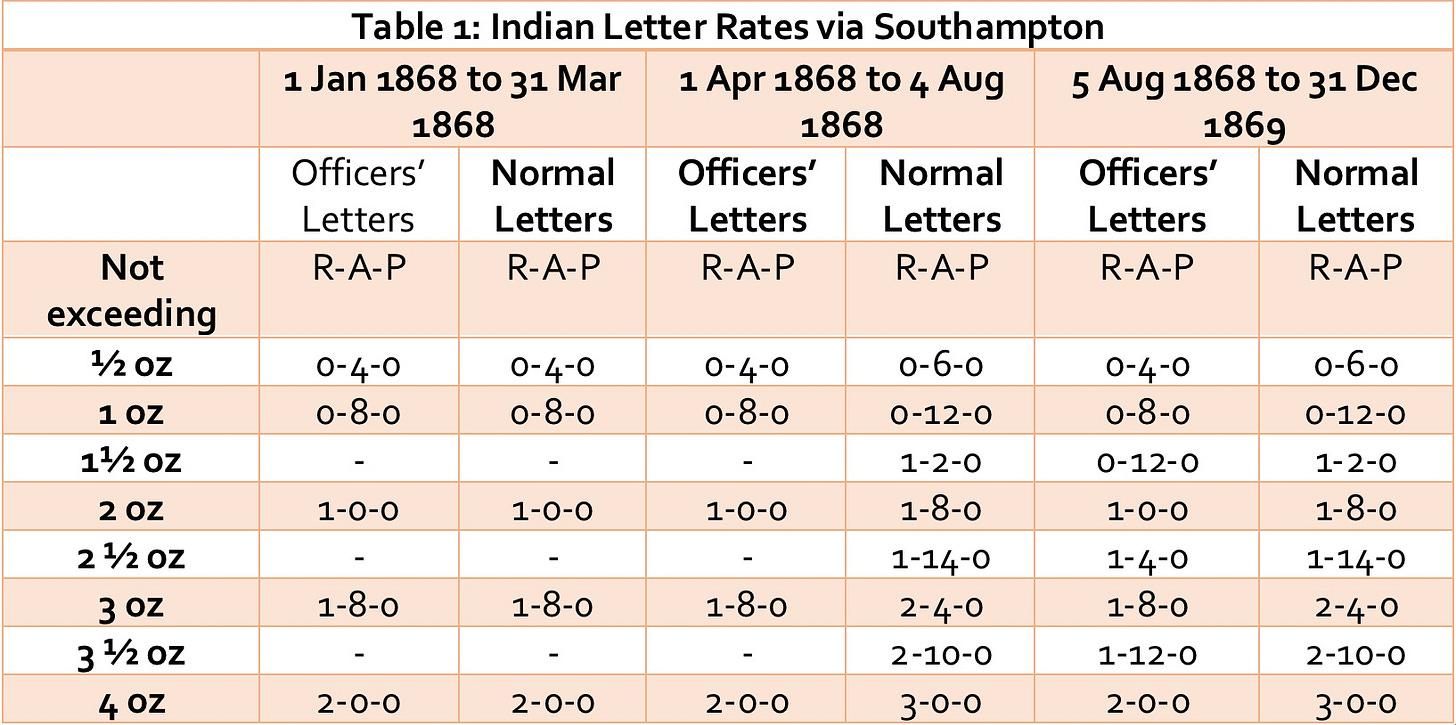

The privilege rates applicable to Officers’ Letters have been tabulated (Tables 1 and 2; also see Figures 5 and 6) along with, for the sake of comparison, the rates available to the general public. It should be noted that letters weighing beyond ½ oz are almost impossible to find.

First, a few general notes would be in order.

Increase in Steam Postage Rates from 1 April 1868

As the consequence of a new packet contract negotiated with the Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Company in late 1867, steam postage rates were supposed to increase from 4a (=6d) to 6a (=9d) with effect from 1 March 1868. However due to delay in receiving the information from London, the Indian post office notified the new dates to be effective 1 April and requested the London post office not to levy fines on letters prepaid at the old rate previous to the latter date.19

Weight Scale

Since 1 June 1863, rates via Marseilles, from/to India to/from Great Britain were on the ½ oz scale rather than the ¼ oz one.

Now, some notes with respect to the concessionary rates.

Start Date of the Privilege Rate

Martin & Blair (pg. 20) mention that the date of commencement of this rate in India is not known and that covers a month or six weeks earlier to 1 January 1868 may be expected; further their Table 2 of postage rates mentions a start date of 27 September 1867 i.e., the date of the Treasury Warrant. Given that the British Treasury Warrant clearly mentions the start date of the facility as 1 January, any date of the concessionary rate usage from India before January 1868 is impossible.

Privilege Rates via Marseilles between January and March 1868

Paragraph 4 of the 27 September 1867 Treasury Warrant stated:

All letters which shall be sent by the post under the regulations of this Warrant shall be subject, in addition to the rates hereby fixed, to the payment of any foreign postage which shall be chargeable thereon

The ‘foreign postage’ in the ‘Via Marseilles’ route was French transit of 2a8p (=4d) per ½ oz. The total theoretical rate hence works out to 6a8p (=10d) per ½ oz.

However, Table 2 of Martin & Blair (pg. 44) has Officers’ rates via Marseilles to be identical to those via Southampton. This is substantiated with some covers seen.

In the absence of any documentation on this subject, one can only speculate that it may have been a combination of two issues that allowed this anomaly. First, both the local and the Bombay foreign post offices may have inadvertently missed the fact that foreign postage was payable in addition to the 4a rate. Secondly, as we have seen, new postage rates could not be implemented by the Indian PO from 1 March and they had suggested to the London PO not to fine underpaid letters from India arriving in UK in March; this may have caused the two letters that I have seen (Figure 7)20 (both arriving that month) to escape postage due markings at the British end.

It may be added here that Jane and Michael Moubray21 are of the opinion:

It seems that the Indian Post Office was prepared to subsidise the latter route (i.e., the Marseilles one), for letters have been seen from India to England addressed via Marseilles and stamped at 4a (=6d)

This is unlikely. As we shall see later (see Note 33), the Indian post office likely did not bear the subsidy and that it was entirely borne by the British post office.

Insufficient Postage on Officers’ Letters

In case of unpaid or insufficient postage, the addressee was charged the deficiency plus a fine of 6d (=4a). (Figure 8) At the time of the introduction of the privileged rate, the fine on Officers’ letters were the same as for the public; however, with effect from 1 April 1868 the fine for the latter was increased to 9d (=6a) while that for Officers’ remained at 6d.

Weight Progression

While the Treasury Warrant dated 27 September 1867 has the weight progression at 1 oz beyond the first oz for all letters to and from East Indies, Australia, and New Zealand (places not named enjoyed a ½ oz scale), the British Postmaster General modified it to ½ oz later; these changes were reflected by the Indian post office in its notice dated 5 August 1868. This is the reason why we see a different set of rates from 1 April 1868 to 4 August 1868 and then from 5 August 1868 to 31 December 1869 in Table 1 and 2 above.

Officers’ Letters with Additional Rates

Very few Officers’ letters exist with additional rates. They are summarised in this section.

Officers’ Registered Letters

Officers’ Letters could be registered and an additional 4a, the same as applicable for the public, needed to be paid. (Figure 9)

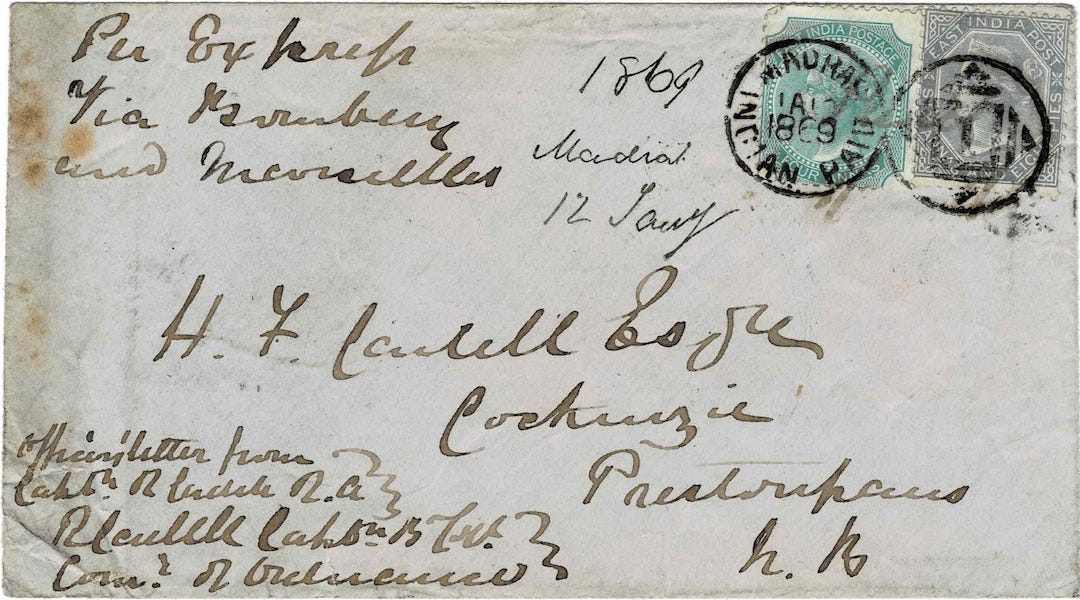

Officers’ Express Letters

The express fee from Calcutta or Madras to Bombay to catch the overland steamer was 4a. This was payable over and above the privilege rate. Given that expresses ran from only Calcutta or Madras22 and given that many officers were serving in far-flung areas, such letters would be some small fraction of all Officers’ letters. (Figure 10)

Officers’ Late Fee Letters

At this this time, late fees of (usually) 8a were payable on all letters posted after the cut-off time over and above the Officers’ rate. (Figure 11)

Withdrawal of the Privilege Rates

In August 1869, (Figure 12)23 the British government decided to withdraw the privileged rates enjoyed by not just army officers but also naval officers. With effect from 1 January 1870, officers could only send letters at the same rates as was applicable to letters sent by the general public. Just as in 1867, the India Office at London informed the Government of India of this decision,24 and the Indian Officers’ rates were withdrawn. (Figure 13)25

The reasons behind the withdrawal were not clearly disclosed. A close reading of the general press as well as some post office documents provide clues.

Abuse of the Privilege

The Times of India26 was of the opinion that the chief reason for the decision was the abuse of the privilege by officers (not just army officers surely but also naval ones) who had resorted to inconsiderate and unfair franking.27 In a letter from H. M. Post Master General’s office to The Under Secretary of State for India,28 the writer alludes to this when he says:

…and, adverting to the difficulties which have attended the arrangement, in the attempt to confine it to those persons for whom alone it was intended, their Lordships have come to a decision that it is not expedient to continue such privileges after the termination of the present year.

Increased Postage Rates for the Public

Another contributing factor may have been the increase in postage rates to/from India for the general public the previous year. The increase had resulted in great objections both in Great Britain and India including by Chambers of Commerce and the general public. The issue had also reached the halls of Parliament where one member wondered:29

…on what principle this privilege was granted…to many commercial and professional men postage was as much a burden as it was to officers of the army and navy.30

Postage Burden on the Colony

Finally, in an answer to a question posed in Parliament to the Secretary to the Treasury, the reason given was:31

…it became necessary for Her Majesty’s Government to look at the matter in relation to the contracts for the packet service, and to the fact that the postage charge very often fell upon the foreign dependencies where the officers were serving. It seemed, therefore, a matter of doubtful expediency that the Government should of their own motion grant a special exemption to their own subjects which fell upon the foreign dependencies.

While this may have been the case in other colonies, it is doubtful if the Indian post office bore the cost of the privileged rate of 2a (=3d).32

In Conclusion

The formation of the General Postal Union (later the Universal Postal Union) in 1874 resulted in a reduction in postage rates amongst the participating countries. Further the great increase in mail volumes over the next quarter century led to the commencement of the Imperial Penny Postage System with effect from 25 December 1898. While Officers’ rates had been abolished three decades earlier, concessionary soldiers and seamen rates of 1d became unnecessary thereafter.

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Max Smith, Martin Hosselmann, Paul Allen, Colin Tabeart, and John Copeland for their valuable inputs as also sharing images of documents, news reports, and covers in their collection. Any feedback can be sent to my email id: abbh@hotmail.com.

The words privileged and concessionary will be used interchangeably in this article.

With effect from 10 January 1840, a ‘single letter’ was later defined to mean one weighing ½ oz or less. Vide Treasury Warrant dated 27 December 1839 published as Supplement to The London Gazette of Friday the 27th of December on 28 December 1839.

Postage Act 1795 (35 George III c.53 dated 5 May 1795).

Postage Act 1815 (55 George III c.153 dated 11 July 1815).

Treasury Warrant dated 11 September 1856 published in The London Gazette of 16 September 1856.

British General Post Office Notice dated 13 September 1856.

Treasury Warrant dated 16 May 1857 published in The London Gazette of 19 May 1857.

British General Post Office Notice dated 8 September 1857.

British Postal Guide dated 1 July 1868.

Martin, D. R., and Colonel Neil Blair. Overseas Letter Postage from India 1854-1876. London: Robson Lowe Ltd., 1975.

Later, in a letter dated 26 May 1869 addressed to the Officiating Secretary in the Financial Department of the Government of India urging for the abolition of this facility, the Director General of Post Office of India, A. M. Monteath, argued that, “these treasury Warrants although professing to lay down the law for the levy of postage in certain cases in India have no legal force in India, except in so far as their provisions are adopted and promulgated by the Governor General in Council under Section 21 of the of the Indian Post Office Act.” To support its view the Indian post office had also received a confirming opinion dated 13 January 1869 from the Advocate General, T. H. Cowie. Published in Proceedings of the Financial Department, November 1869.

Logically a notice by the Indian post office should have been issued on the subject but it is not traceable; it is quite likely that it was never issued.

Clarified as a measure of caution in Indian government’s Financial Department notification dated 30 December 1867 published in The Gazette of India of 4 January 1868. An Indian post office notification dated 5 August 1868 states that all military officers serving under the orders of the civil administration, for example belonging to the survey, public works, education, telegraph, post office, police, jail, as well as secretaries to the government, cantonment, magistrates, commissioners and deputy Commissioners, civil surgeons, and chaplains (but not Presbyterian chaplains attached to some Highland Regiments in India), and not under the orders of the Commander-in-Chief, are regarded as being in civil employ.

Treasury Warrant dated 1 May 1868 published in The London Gazette of 8 May 1868.

On the other hand, vide the aforementioned Treasury Warrant of May 1868, schoolmistresses in the army, whether at home or abroad, could send and receive letters not weighing above ½ oz for only 1d! Clearly, there must have existed disparities in pay scales between schoolmasters and schoolmistresses that a much lower rate (the same as soldiers and seamen) were applicable to the latter.

Notification dated 5 August 1868 issued by A. M. Monteath, Director General of the Indian Post Office.

Notification dated 12 January 1869 amending the 5 August 1868 notification. This rule, or rather “recommendation” was not enforced as one sees letters written by Commanding Officers not so precisely endorsed.

Introduced in the notification dated 5 August 1868.

The Indian post office received instructions from H. M. Post Master General on 2 March 1868 and a notification was issued on the same date. The initial print of the notification in The Gazette of India of 14 March 1868 mentions in the footnote, “Adverting to the lateness of the receipt of intimation of the charges notified above with effect from the 1st March, it has been suggested to the London Post Office, that no fine should be levied on Letters prepaid at the old rates which may be sent from India by the Bombay Mail of the 7th March.” However, the footnotes of the same notification published in The Gazette of India of 21 March 1868 changes the effective date to 1st April.

One of the letters is illustrated here and the other is illustrated on page 53 of Martin & Blair (now in the Martin Hosselmann’s collection).

Moubray, Jane, and Michael Moubray. British Letter Mail to Overseas Destinations 1840 to UPU. 2nd ed. London: Royal Philatelic Society, 2017.

There is some evidence that expresses could be booked from other places along the Calcutta-Bombay or Madras-Bombay route like Allahabad or Bangalore. See Smith, Max, and Robert Johnson. Express Mail, After Packets, and Late Fees in India Before 1870. Wheathampstead, Herts, UK: Stuart Rossiter Trust, 2007.

Treasury Warrant dated 17 August 1869 published in The Edinburgh Gazette of 24 August 1869.

Letter No. 87 dated 16 September 1869 from The Secretary of State for India to The Government of India. Published in Proceedings of the Financial Department, November 1869

This withdrawal must have been met with glee by the Indian post office. They were never in favour of this arrangement since it led to a lot of hardships at the post offices at Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay in making up the letter mails. Further, in the opinion of the Director General, the privilege was “to a large extent held in contempt” and the trouble faced by officers in getting the letters countersigned by their commanding officers or head of the department outweighed the two-anna benefit. Letter dated 26 May 1869 from The Director General of the Post Office of India to The Officiating Secretary to the Government of India, Financial Department.

The Times of India dated 20 December 1869.

Earlier in late-1868, H. M. Post Master General had disallowed officers’ from affixing their names to their wife’s letters! Post Office of India notification dated 30 November 1868 quoting a H. M. Post Master General ruling of 7 October 1868.

Letter dated 31 August 1869 from Frank Ives Soudamore of H. M. Post Office to The Under Secretary of State for India.

House of Commons proceedings of 7 July 1868; the member in question raising these questions being Robert Wigram Crawford.

Whether officers were burdened with high postage rates would be a matter of debate. According to Dr Gajendra Singh of the University of Essex, in the 1860s, a middle-ranking European officer such as a colonel would earn Rs. 1,478, a lieutenant-colonel Rs. 1,032 and a major Rs. 929 per month. Meanwhile Indian officers earned between 5-10% of their European counterparts and a Sepoy earned just Rs. 7, which was often lower than the cost of subsistence. See https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Were-Army-pay-and-perks-better-under-the-British/articleshow/47952190.cms (accessed on 15 Aug 2020).

House of Commons proceedings of 23 May 1870.

In the letter dated 26 May 1869 referred to above, the Director General, apart from requesting for the abolition of the officers’ rates, also requests for a reduction in the postage between India and Great Britain by 1d. He says, “I am aware that in a previous correspondence a larger reduction was proposed, and that the proposal was negatived by Her Majesty’s Government, but I think that if India is willing to give up the privileged rates on the letters of military officers, the question of making a small immediate reduction of the general rate may fairly be revived.” This indicates that the concession of 2a (=3d) was being borne not by the Indian post office but by the British one.