This article was first published as “Cecil Rose and his Skullduggeries” Philatelic Literature Review 72 no. 1 whole no. 278 (First Quarter 2023).

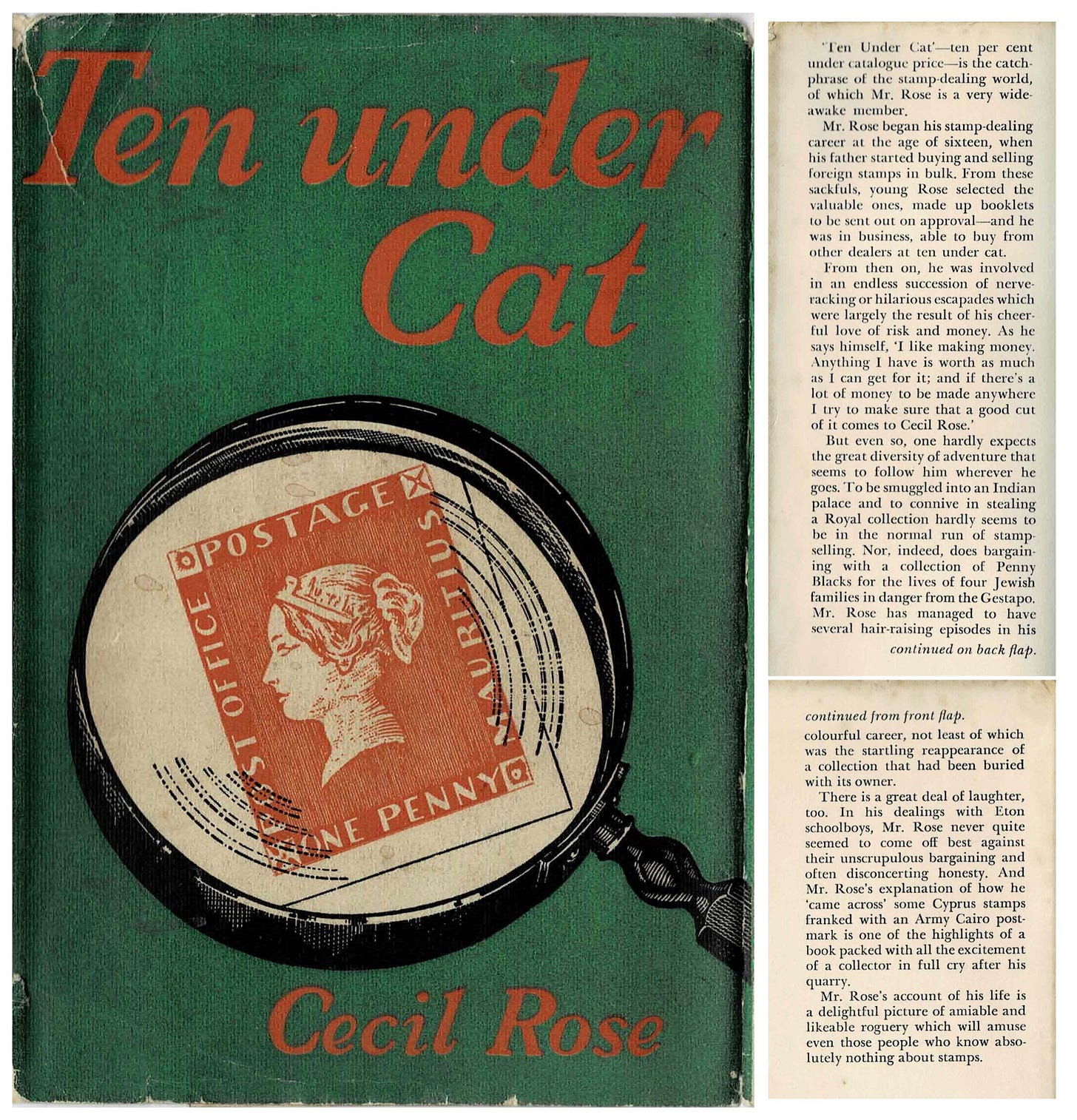

A few months back, I bought a book titled Ten under Cat (Figure 1) by one Cecil Rose (Figure 2). I had never heard of its author and had little idea of its contents, apart from the fact that it was the memoirs of a stamp dealer; I love such books! It turned out to be a quick read and I finished its 160 or so small format pages within a few hours.

First, a bibliography of the book:

Rose, Cecil, and Edward Lanchbery. Ten under Cat: Reminiscences of a Stamp-Dealer. London: Cassell & Company Ltd, 1958

159 + (1) pp, numbered in Roman numerals till v, then a blank page, and then 7-159. Hard Bound in Dark Green Cloth with gilt lettering on spine. DJ. Price 10/6 on dust jacket front panel.

Lanchbery seems to be the ghost writer as the title page says, “…by Cecil Rose as told to Edward Lanchbery.”

So, how does the book get its name? At one page, Rose says that when he started dealing in stamps, he “…bought as one of the trade on discount terms. ‘Ten under Cat’–ten per cent under catalogue price–the phrase rolled glibly off my tongue.” On another, he tells a buyer, “I’m charging you ten percent under catalogue price. Honestly you won’t do better. I swear it.”

To any serious stamp collector, such (and other) statements sound incredulous, many of his facts and specially his numbers, which often went into many tens of thousands of pounds (the value of one pound then equates to about 25 today), sound fictitious. To top it all, Rose relates some dubious transactions with great relish; if some of them indeed took place, why should he publish them and risk getting into trouble?

So, I went online to read more about the man. And I realized that Rose was a much more colorful character than the average stamp dealer! And trouble did eventually catch up with him.

Early Years

Cecil Rose was born c. 1903/1904.1 From his book, we learn that his grandparents had fled the Continent and settled in England. Rose’s mother ran a large house of 13 in the (then) village of Salford near Manchester, Rose had three brothers and seven sisters. Rose’s father was a jeweler but was “too religious to be a good businessman.” He had no shop or office but worked from home, buying, polishing, cutting, setting stones, and reselling them privately. He later started trading in stamps in bulk.

Rose’s ‘eureka’ moment was when he was 16 and wanted a bicycle. His only wealth was in stamps (which he had bought for full catalogue). He took to a dealer enough stamps of a catalogue value to cover the cost of the cycle. And learnt the lesson that he wouldn’t get more than a fifth of the catalogue for the two or three stamps that the dealer was interested in.

Violá, Rose set about preparing approval sheets and selling stamps at catalogue (though one wonders which collectors pay full catalogue?) In 1926, the family moved south to be close to major stamp hubs of Europe. After operating for five years from home at Finchley, his father and he opened a shop in Oxford Street in London.

Unfortunately, Rose’s father passed away just a year later. Still young, in the following years, Rose learnt the trade the hard way. He was often the target of “petty frauds and big-time confidence tricksters.” Nevertheless, slowly business grew, and he became known as ‘Rosie’ to collectors and dealers.

The advent of World War II made his deposit his best stock at the bank, close his shop, and enlist in the army. He went to the Middle East as a warrant officer in the Field Security Force. When there, he admits that he franked some high-value Cyprus stamps with the Middle East Field Post office Cairo number and later sold them as freaks for good money.

High Street, Eton

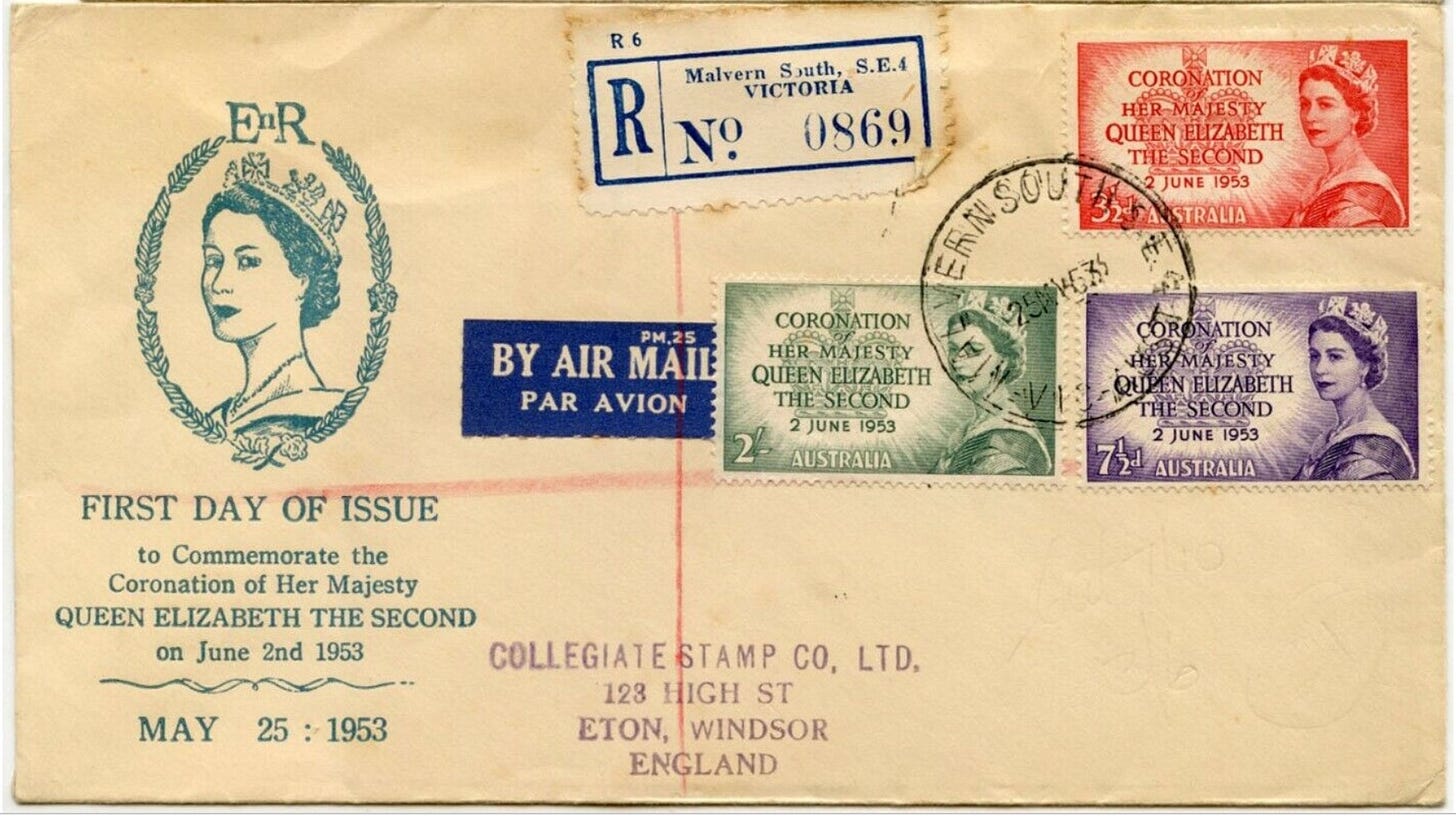

After the war, Rose returned to his stamp business. His Oxford Street premises had suffered in the blitz. After operating from his house at Windsor for a while, he got to know about a shop in High Street, Eton, Windsor from a solicitor friend. A South African, who was returning to his country, held the lease. Rose bought the lease and towards the end of 1945 opened his stop shop.

Rose gave a talk on stamps to the Eton College Philatelic Society and soon his shop became the Society’s headquarters. Due to its proximity to the College (just about half-a-mile), his shop became popular with his wife, Mina, helping him out. So popular that, over the following decade, he claimed he had an average of four hundred College boys on his list of regular customers (Figure 3).

In his book, Rose devotes a good-humored chapter to his dealings with Eton school boys. They were either looking for a bargain or trying to pull his leg by making him search for non-existent stamps or spoil his dealings with adult collectors by making comments on Rose’s unfair prices.

The Bucket Shop

Collegiate Stamp Co. Ltd. (Collegiate) was incorporated in April 1950 with the objective of taking over Rose’s stamp business which it did for £10,000 (the amount was credited to Rose’s loan account in the company). Its original premises was in Rose’s High Street shop (Figure 4). The reason for the word ‘Collegiate’ in the company’s name is obvious.

Collegiate doesn’t seem to have prospered much apparently since Eton College boys were much too knowledgeable and smart! During his trial, the prosecuting mentioned that the Eton shop was bringing in only £20 a week but Rose had “ideas of becoming Britain’s No. 1 stamp broker.”

Soon thereafter, Rose started his monkey business. He opened a shop in the Strand at London, the mecca of stamp dealing, where “the net was cast wider with the object of enticing bigger fish into it.”

Apparently, Rose started sending circulars / prospectuses to rich collectors asking them to let him handle their stamp deals. His idea was to deal in stamps similar to how stockbrokers dealt in shares. His circulars read: “Do you want a tax-free investment with guaranteed capital appreciation? If so, we can give it to you.” He gave investors an undertaking to buy back stamps at an agreed increased value with a few months.

He listed the Duke of Kent and Prince William of Gloucester (a story about the latter at his Eton Street shop appears in his book) as amongst his clients. Likely so that he could entice the high and mighty to part with their money. Apparently, he could be so persuasive as to “charm birds out of trees.” Among those seduced were a peer’s two sons (Hugh Waldorf Astor and John Astor, second and third sons of Lord John Jacob Astor, 1st Baron of Hever), a vice-admiral (Sir Charles Hughes Hallett), and other wealthy men and women, all of whom put money in Collegiate.

Initially, when Rose was paying back investors, it wasn’t from profits but from other people’s money – à la Ponzi scheme. This wasn’t, of course, sustainable. Later, when investors asked for their money and profits, he gave evasive replies. The scheme went on for about six to seven years until, on January 13, 1958, a creditor’s petition was allowed by a court which ordered the commencement of winding up of Collegiate; by July 1958, the company was wound up. The statement of affairs showed a loss of £178,047 but it was thought that the loss could well be in the region of £250,000.2

It is interesting to note that Ten Under Cat was published sometime in the beginning of January 19583 just as Rose’s schemes were unraveling. I speculate that Rose could see his company and himself on the brink and he needed some positive publicity; a witty short book of his memoirs with fantastic, intriguing, incorrigible stories of his life and stamp dealings would be perfect. And a possible continuance of his shenanigans; after all the last chapter of the book has the title ‘Making Money out of Stamps’ where he presents his thoughts on the subject, likely aiming at the gullible public.

For obvious reasons, Rose ‘forgets’ to mention his skullduggeries with respect the 1957 Scout Jubilee Jamboree. This episode raises temperatures to this day, especially amongst Boy Scouts.4

Scout Jubilee Jamboree and Rose’s Skullduggery

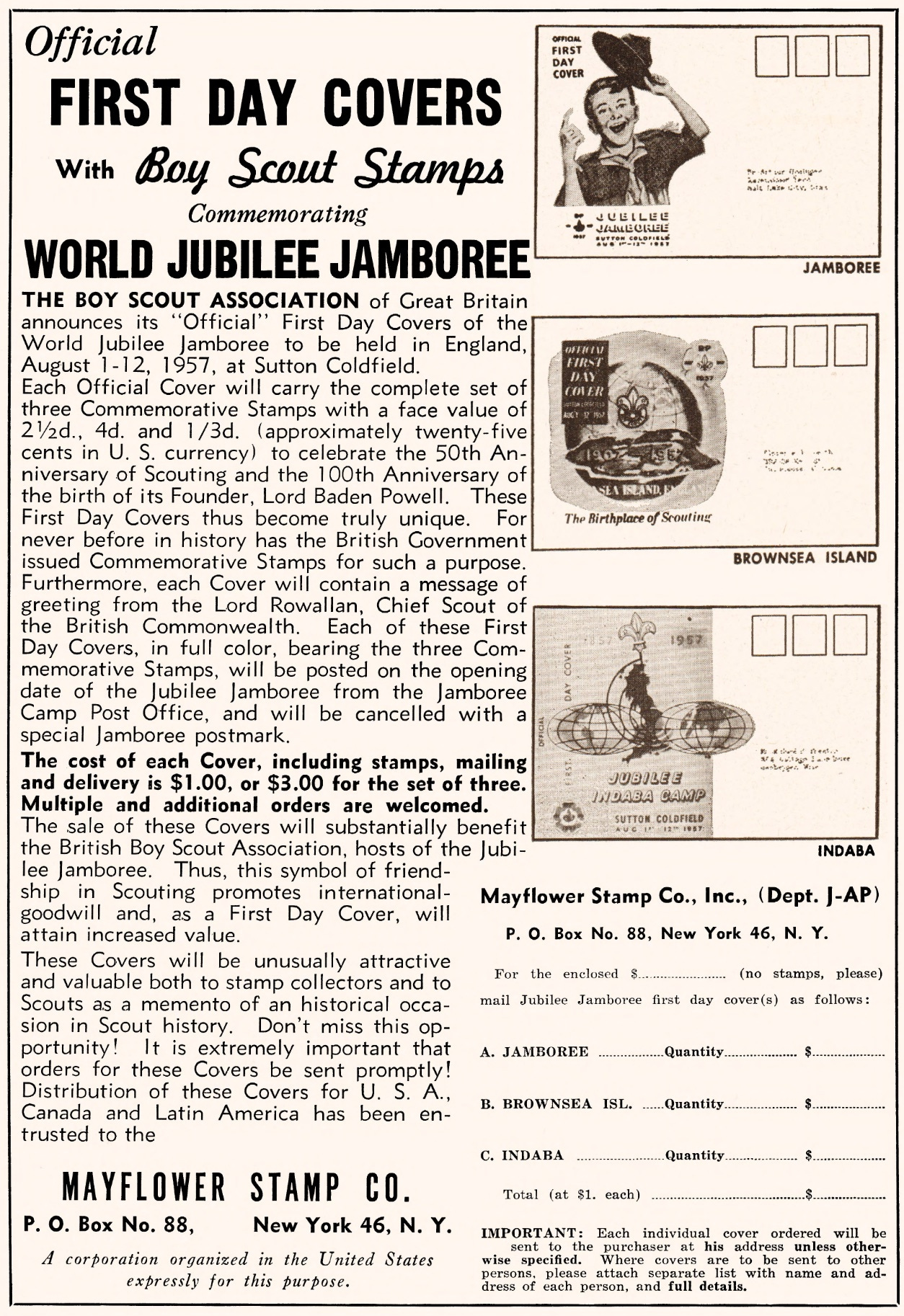

After hectic lobbying by the Boy Scouts Association (BSA), it was announced in mid-1956 that the Post Office would be issuing a set to commemorate the Jubilee Jamboree of the Boy Scouts at Sutton Coldfield,5 in values of 2½ d, 4d, and 1s 3d, for a total face value of 1s 9½ d. They were issued on August 1, 1957 (Figure 5).

Rose apparently wrote to the BSA proposing that he would supply souvenir first day covers (FDCs) bearing these three stamps for 6s 6d6 each (the initial proposed price was 6s), a premium of more than 250% on the face value of the stamps. Further, he estimated that six million covers would be sold (the number was reduced to two million by January 1957). A considerable profit was to be made and hence Rose promised to hand over a minimum of £50,0007 to the Boy Scouts Association.

On September 6, 1956, the BSA made arrangements that the Mayflower Stamp Co. Ltd. (Mayflower) be the sole distribution agent of (official) FDCs for the Jubilee Jamboree. Mayflower has been specifically created for this purpose. Rose was one of the five directors, the managing director in fact, while the other four were “names which would add distinction to any board.” To bring about legitimacy to the venture, Rose had cleverly invited respected gentlemen to the board, one of whom was the Marquess of Donegall to become the chairman of this company. The Marquees was told that Mayfair was a party charitable, partly profit-making concern; the peer was even induced to invest £500 in the company!

There was disquiet in the post office regards this arrangement. On November 3, 1956, the Assistant PMG discussed the proposals regarding the Mayflower arrangement with Sir John Wilson, Keeper of the Royal Philatelic Collection (Figure 6). Sir John had strong opinions about releasing stamps outside the Post Office before the issue date so that Mayflower could affix them on covers.8 He also viewed involvement with the Mayflower with great concern. The Director General was concerned that the Post Office could come under strong criticism from other stamp dealers by giving preferential treatment to one company. He felt the Post Office would have to make it quite clear that any person or dealer could obtain a FDC without having to buy it from Mayflower.9 The PMG advised a certain amount of caution regarding the Post Office’s dealings with the company, pointing out that Rose released a figure to the national press that his company was expecting to sell three million FDCs for the Queen’s Coronation in 1953, whereas the actual figure was 6,700 covers. And now he was now estimating a sale of six million Boy Scouts covers.

Notwithstanding the apprehensions, the project moved forward. Mayflower produced official first day covers in 12 designs, four of which some were used for the Jamboree, on such themes as (a) Jubilee Jamboree (gathering of scouts), (b) Jubilee Rover Moot (gathering of Rover scouts), (c) Jubilee Indaba Camp (gathering of scout leaders), and (d) Brownsea Island (the first scout camp). The covers were cancelled with the special postmark slogan ‘Jubilee Jamboree - Sutton Coldfield’ and posted from the Jamboree Camp Post Office (see https://www.gbstamprolls.com/queen-elizabeth-ii/boy-scout-jamboree) for images).

Mayflower advertised the offering of the first three designs (a, b, and c) widely, both via flyers as well as advertisements in the press (Figure 7). The former, circulated amongst scouting groups and others, mentioned that the cancellations applied to the covers would make them “unique” and that should cause them to “increase in value from the date of posting” (never mind the price which was more than three times the face value of the stamps!) Rose, via Collegiate, was believed to have collected more than £40,000.

It was later revealed that only 60,63210 covers were produced, a fraction of the original estimate. The high price of each FDC would have been one of the main reasons for the poor demand especially from the Boy Scouts who could hardly be expected to have such royal sums on them. Rose, via Mayflower, paid the Boy Scouts’ Association £95711 and pocked the rest.12

Arrest and Charges

Just before midday on April 29, 1960, Rose was arrested at his office in Gray’s Inn Road, London. The arrest was on a warrant granted to the Board of Trade, who preferred 16 charges (which increased to 20 by the time his trial ended) against Rose under the Prevention of Fraud (Investments) Act, 1939, the Larceny Act, 1916, and the Companies Act, 1948.

Rose was taken to the Cannon Row Police Station. When asked by the Scotland Yard’s Fraud Squad if he had anything to say, Rose mentioned that the charges were untrue. In the afternoon, he appeared at the Bow Street Magistrate’s Court. He was remanded on bail in his own recognizance of £1,000 and a surety of £1,000.

The first of 16 charges alleged that on or about July 27, 1954, at the National Liberal Club, Rose induced John Astor (Figure 8) to enter into an agreement regarding the purchase of 3,000 sets of British Crown Colonies Victory stamps issue by falsely stating that the number of the issue was limited, that he could purchase and control the whole issue, and that the stamps would increase in value in short time. Two further charges alleged the fraudulent conversion from Astor of 1,511 sets of stamps including Crown Colonies, Northern Rhodesian, Southern Rhodesian, and Nyasaland issues between 1954 and 1958.

Another two charges alleged that Rose induced High Waldorf Astor to enter into an agreement to buy five sets of Tristan Da Cunha stamps by recklessly making a forecast that they had great investment possibilities and over 150 sets of Burma military administration stamps by predicting that they would double or treble in value. Another charge alleged the fraudulent conversion of £315 worth of St. Helena stamps from Waldorf Astor.

Four more charges involved alleged agreements or fraudulent conversion of stamps belonging to Sophie Germaine Gasner. A further charge alleged the fraudulent conversion of £600 worth of Jubilee Jamboree stamps from Vice-Admiral Sir (Cecil) Charles Hughes-Hallett (Figure 9) in London three years ago.

There were other charges of fraudulent conversion of stamps belonging to Alan Allen and Honor Riddell.

Rose was also charged with three offenses under the Companies Act of being concerned in the management of Collegiate and Mayflower when he was still bankrupt, and with failing to keep proper books of account for Collegiate before its winding up.

Initial Hearings

On June 9, 1960, opening the case for the prosecution at Bow Street, Sebag Shaw, counsel for the Board of Trade, accused Rose of operating his business “with the object of filching large sums of money from people whom he persuaded to buy stamps, not in the ordinary way of stamp collecting but as an investing. He said that the accused was “conducting a bucket shop, except that his stock-in-trade was not securities in the ordinary way but stamps.” He said, “The pots are kept boiling and the investors are kept happy until such time as they begin to wonder if they will ever see their money.”

At the end of Shaw’s opening address, Mr. Gerald B. Owen, representing Rose, said, “Defendant has said all along there has been no fraud whatsoever on any of these charges.”

On the first two days as well as on subsequent hearings, witnesses reveled the shenanigans of Rose. Appearing as the first witness, the Hon. John Astor said that he agreed to buy stamps on Rose’s false assurance that he could purchase and control the whole issue, which he claimed was limited in supply. But apart from receiving £900 he never saw the balance of his money.

The Hon. Hugh Astor, who was also the Deputy Chairman of The Times Publishing Co. Ltd., said that he paid £217 10s for some Burma stamps, being assured that in three months they should be worth double. However, he never received any money from either Rose’s company or from the man himself.

One John Arnold testified that he made Rose’s acquaintance when he walked into his Eton shop in 1954 to make a simple purchase. By September, he had invested £2,200. Over time he joined Collegiate as a part-time salesman and later assisted at the firm’s Strand shop. In November 1954, Arnold was made a director of Collegiate, but he never attended a board meeting or took part in the company’s business. Over three years and before he left the company in 1958, he handed over nearly £24,000 to the company including by borrowing money from his bank by providing as collateral rent from property he held. He got, in return 5,000 shares in a stamp company; those shares were now worthless.

Yet another conned, Vice Admiral Hughes-Hallett said that in the beginning of 1957 he invested £600 in some Boy Scout stamps having received an assurance that he would get back a minimum of £850. Rose had told him that he would make a probable profit of 200 percent from handling the Jubilee Jamboree FDCs. When his solicitors wrote to Rose, he received payments for £100, £50, £25, and £10 (note the sums declining with time likely as money ran out), the last coming in a few weeks earlier.

Another witness, Major Martin Gubbins, company director of Trevor Wood, Ascot, said that in 1956 he had two successful transactions with Rose. Later Rose told him of his Mayflower venture which the major thought he might make a killing in. He invested £500 and his two sisters £250 each. Apart from a cheque for £25 received 12 months prior, he has received nothing except “further promises.”

Mr. Ronald Gardner, acting for one Mr. H. Sawbridge, said he had paid Rose £8,000 for buying stamps. Of this, only £2,000 was repaid and in October 1956, Gardner had threatened proceedings. In November 1957, Sawbridge received a cheque for £6,911 which was postdated to March 1958. This wasn’t accepted as it was dated so far ahead and since then no more money was forthcoming.

The Marquess of Donegall, appearing as a witness, said that he accepted an invitation from Rose to become the chairman of Mayflower but that he has nothing to do with its day-to-day administration. While £50,000 was promised to the Boy Scouts Association, the Marquess said he believed some installments were paid but the reminder wasn’t made since the money was not there.

Other witnesses included Arthur Robin Hill who said he lost £9,000 and Sophie Gassner who invested £2,600 but recovered only £1,000.

Trial and Sentencing

Rose was committed to trial at Old Bailey on 20 charges. He pleaded ‘not guilty’ to all of them. On November 28, 1960, the trial opened and lasted three weeks. The Queen’s Counsel, Neville Faulks, brought out all the trickeries of Rose out in the open. He clarified the three types of frauds of Rose. The ‘investment fraud’ was getting people to buy stamps as investments by making reckless statements and promising false promises concerning the extent to which stamps would likely increase in value within a short time. The ‘fraudulent conversion’ was the practice of inviting the public to invest in stamps which Rose would retain and sell at a profit at the opportune time. This was the fraud most people fell for. The third type of fraud concerned the Boy Scouts Jamboree wherein Rose collected £40,000 but failed to return most of it.

The jury took four and half hours to find him guilty on 12 counts involving fraudulent conversions, false pretenses, and carrying on business when an undischarged bankrupt. He was found not guilty on eight charges of recklessly making misleading or deceptive forecast and of fraudulent conversion.

On December 19, 1960, Judge Aarvold sentenced him to six years’ jail and barred him from management of any company for five years after the end of his sentence. He told Rose,

There was a fraud of which you were well aware when you committed it….It was varied in its design and prolonged in its operation…It involved obtaining the trust of your victims and then avoiding discovery by falsehoods, evasions and false promises….It is obvious to anyone that you are a man in whom it is extremely dangerous to place any trust or reliance.

Further, with reference to the Boy Scouts Jamboree, he said,

…you did not hesitate to use the fair name of the Boy Scout’s Association to further your frauds.

Epilogue

Philatelic rascals and ruffians of all sorts have been recorded since the beginnings of stamp collecting in the 1860s. Rose was not the first, and certainly not the last, who tried to scan and defraud the unsuspecting. So long as (even supposedly sophisticated and shrewd) people get carried away by greed and too-good-to-be-true schemes, conmen such as Rose will be around to dip their hands into their pockets.

After the trial, one does not hear of Rose. He seems to have vanished into obscurity. If anyone has any further information, please get in touch with the editor or me.

Acknowledgements: I thank Scott Tiffney, librarian of the APRL, for help me with the scans of the philatelic articles cited below. Feedback is always welcome; my email address is abbh@hotmail.com.

References

“Boy Scout Jamboree,” GB Stamp Rolls, accessed January 10, 2023, https://www.gbstamprolls.com/queen-elizabeth-ii/boy-scout-jamboree

“Current Comment: Private Jamboree.” Stamp Collecting. November 30, 1956.

“Philatelic Fortune for Scouts.” Bristol Evening Post. March 11, 1957.

“£50,000 for Boy Scouts from Stamps.” Torbay Express and South Devon Echo. March 15, 1957.

“£95,000 loss on Scout Jamboree.” Belfast Telegraph. July 17, 1958.

“Stamp Man on 16 Charges.” News Chronicle. April 30, 1960.

“Stamp Dealer ‘Rosey’ of Eton Accused.” Daily Herald. April 30, 1960.

“Cecil Rose Arrested and Remanded.” Stamp Collecting. May 6, 1960.

“Cecil Rose on Fraud Charges.” The Philatelic Trader and Stationer. May 13, 1960.

“Court Told of ‘Bucket-Shop by Stamp Dealer’. Express & Echo. June 9, 1960.

“‘Bucket Shop’ in Stamps, Court Told.” The Birmingham Post. June 10, 1960.

“Stamp Deals like Bucket Shop, Court Told.” News Chronicle. June 10, 1960.

“Accused Stamp Dealer: More Evidence.” The Birmingham Post. June 11, 1960.

“Cecil Rose “Ran Bucket Shop”. Stamp Collecting. June 17, 1960.

“Lord Donegall a Witness in Stamps Case.” Belfast Telegraph. September 15, 1960.

“Marquess a Witness in Stamps Case.” Express & Echo. September 15, 1960.

“Torquay Witness on Deal in Stamps.” Herald Express. September 15, 1960.

“‘Stamp Dealer could Charm Birds out of Trees’ Q.C.” The Daily Mail. November 29, 1960.

“Six Years for Rosey of Eton.” Daily Herald. December 20, 1960.

“6 Years for Rosey of Eton.” Daily Mirror. December 20, 1960.

“Rise and Fall of Cecil Rose.” The Philatelic Trader. December 9, 1960.

“Six Years Gaol Sentence for Rosie the Charmer.” The Philatelic Trader. January 6, 1961.

[Nodder, Wilf.] “A Rose by any Other Name Smells…” The Journal of the Scout Stamps Collectors Club. 5 no. 1 (January 1961): 33

Page, Derrick. “The 1957 World Scout Jubilee Jamboree,” The Postal Museum, accessed January 10, 2023, https://www.postalmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Stamp-History-1957-Scout-Jamboree.pdf.

Thomas, Gilbert. “Round the Shelves.” The Birmingham Post & Gazette. January 28, 1958.

Walker, Colin. “1957 Jubilee Jamboree ‘Official’ First Day Covers: A Tale of ‘Skulduggery’” Scout and Guide Stamps Club Bulletin. 63 no. 1 whole no. 353 (Spring 2019):

At the time of his trial in 1960, newspapers reported his age at either 56 or 57. I haven’t been able to find the exact date of his birth; or death, for that matter.

This equates to more than £6 million in today’s numbers.

Reviews of the book were published in the popular press late January 1958. Since the copyright page of the book mentions the year of publication as 1958, this implies that the book came out in the beginning of January 1958.

The reader is directed to articles by Page and Walker and the website of GB Stamp Rolls for further information on the stamps and FDCs of the Jubilee Jamboree.

A Scout Jamboree, Scoutersʼ Indaba (meeting) and Rover Moot was held from 1-12 August 1958 in Sutton Park, a natural park of 2,400 acres, in Sutton Coldfield, Warwickshire. The Jamboree marked dual milestones as it was both the 50th anniversary of the Scouting movement since its inception Brownsea Island and the 100th anniversary of the birth of Scouting's founder Robert Baden-Powell. About 33,000 Scouts from 90 countries camped for 12 days.

More than £8 in today’s money; a significant sum for one FDC. These official FDCs are available on eBay for a few pounds / dollars to this day.

This is a huge sum; about £1.3 million in today’s equivalent.

In a meeting dated October 24, 1956, between the BSC, Mayflower, and the Assistant PMG, Mayflower requested that the three stamps be given to them in advance so that they could affix them on the 6 million covers. The post office was very averse to the idea since it was impossible to guarantee that, of the 18 million stamps, none went astray. Finally, stamp affixing machines made by Vacuumatic Ltd. was purchased for this purpose.

The Post Office sold FDCs for 2s each, but orders needed to be for no fewer than 60 covers. This meant that the only buyers would be dealers. The covers had to be provided by the customer bearing their full postal address and had to be of one of three specified sizes. Many ‘unofficial’ FDCs were thus created.

Page (1992) quotes the Stanley Gibbons Specialised Catalogue which states that 60,632 covers were ‘serviced’. Does this number apply only to the Mayflower FDCs or to both the Mayflower and the Post Office ones?

This number was revealed during Rose’s trial. Nodder (1961), however, mentioned the amount as £700.

In July 1958, the provisional account of the Jamboree showed a net loss of £96,500; it is not known whether this loss included the amounts not received from Mayflower. The loss could have been lower had Mayflower paid the BSA the minimum amount of £50,000 it has earlier guaranteed.