British Crutched Cross on Indian 'King’s Post' Letters, 1816-19

The British PO demands its pound of flesh

This article was first published as “British Crutched Cross on Indian ‘King’s Post’ Letters, 1816-19”, India Post 58 no. 4 whole number 223 (October - December 2024): 155-167. India Post is the journal of the India Study Circle for Philately.

The ‘crutched cross’ (Figure 1) handstamp of London was introduced in 18171 to cancel postally applied errors on letters.

This article proposes to discuss letters which travelled between India and Great Britain (GB) during the period when the Postage Act of 1815 (55 Geo 3 c. 153 dated 11 July 1815; also known as the ‘India Packet Letter Act’ or ‘King’s Post Act’) was in force and why some of them have this crutched cross applied on them. While the first two reasons are simple enough, it is while discussing the third one that one realises how fascinating postal history can be. I have included extensive endnotes with the objective of making the article as self-contained as possible.

Application of ‘BOMBAY PACKET-LETTER’ on Ship Letters

Unlike their Calcutta and Madras counterparts, Bombay GPO never got around to making a ship letter handstamp locally.2 Hence, in their judgement they thought it fit to apply the oval ‘BOMBAY PACKET-LETTER’ (Giles SD2) even on letters carried by ships not designated as packets i.e. private ships.

Ship Letter Postage Collected in India

News of the passage of the 1815 Act reached India only in March 1816 when the first designated packets and ships docked ashore. The Act had its peculiarities, and it was not always correctly understood by His Majesty’s Deputy Post Masters General at the three presidency towns. The latter were actually Post Masters General of the Presidency Post Offices who had been designated as deputies by His Majesty’s Postmaster General for the main purpose of accounting for and collection of revenues.3

For instance, under the terms of the 1815 Act, sea postage (or King’s postage) on letters sent from India on designated packets could be collected either in India or in GB, at the option of the sender. But sea postage on letters sent by ships not designated as packets were not supposed to be collected in India. Initially, the three Presidency General Post Offices (GPO) at Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay, interpreted the relevant clauses incorrectly4 and allowed prepayment until about April 1817 (possibly June 1817 in the case of Bombay) when they received a letter of admonishment from London!5

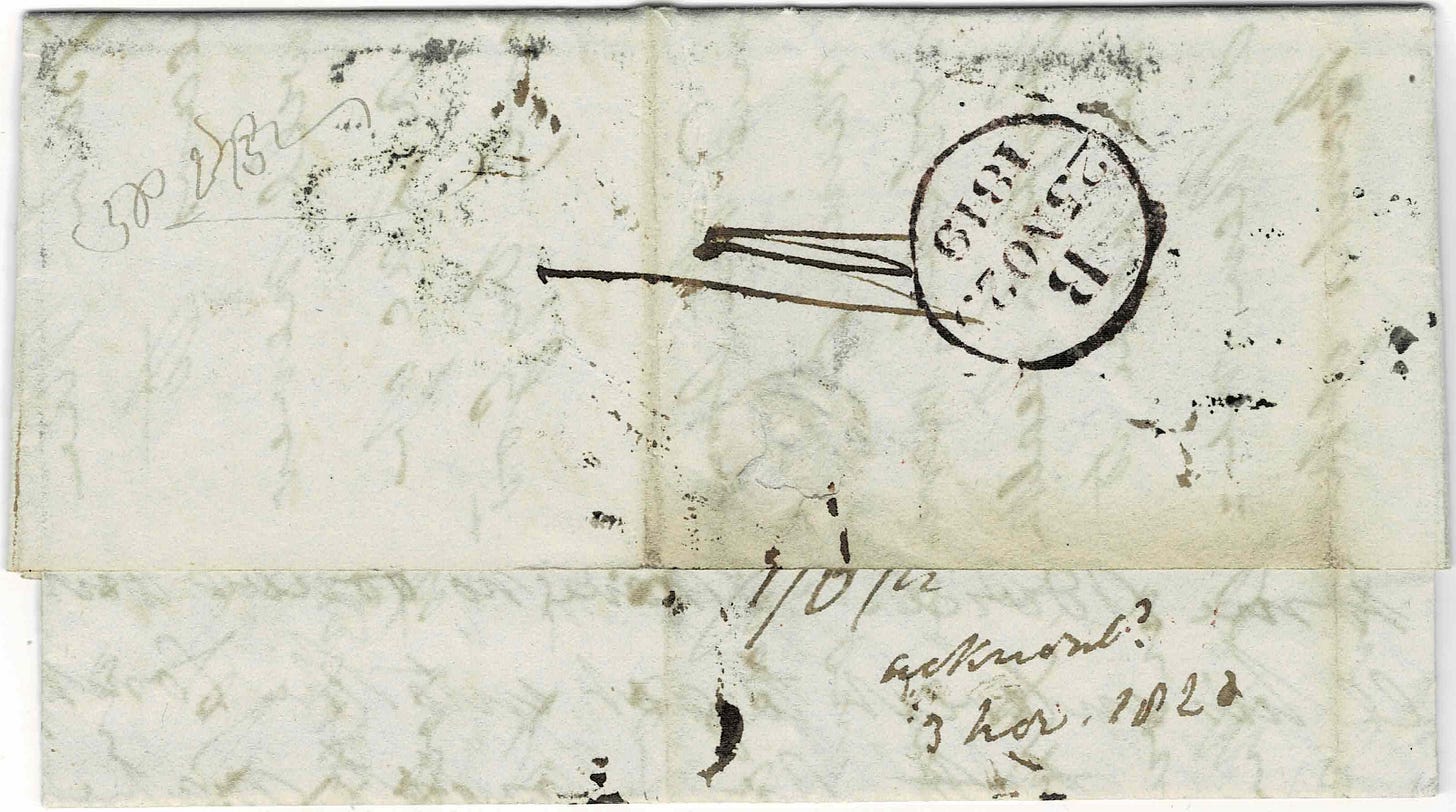

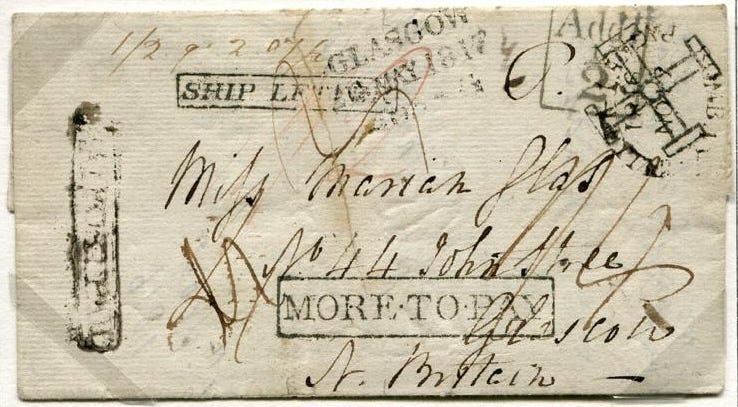

Consider the letter shown as Figure 2. Written on 16 November 1816 at Poona, the letter prepaid the inland postage to Bombay (not shown on the letter) as well as, incorrectly, the ship letter postage of 1s2d6 or 2 quarters 7½ reis in Bombay currency (see manuscript ‘1/2 . q. 2. 07 ½’ on top as also the ‘BBAY POST PAID’ handstamp).7 This rate applied since the letter was being carried by Orpheus, a private ship.

On arrival in GB, the London GPO noticed that Bombay GPO had applied an oval ‘BOMBAY PACKET-LETTER’ on a ship letter and considered it to be erroneous. So, it cancelled the mark with a crutched cross. It also applied a rectangular ‘SHIP LETTER’ stamp. Total ship postage due was assessed as 1s4d, which gave credit of 1s2d already paid at Bombay.

Ship Letter Postage Not Collected in India

A letter from ‘Camp Nandoora’ to Edinburgh datelined 12 November 1816 is illustrated as Figure 3. Unlike the letter before, ship postage on this was not collected in advance as evidenced by the ‘B.BAY SHIP PGE. NOT PAID’ stamp. Even though it was a letter sent by a private ship, Bombay GPO applied the ‘BOMBAY PACKET-LETTER’ on it. On arrival, once again, London GPO cancelled the mark with a crutched cross.

Abolition of the 1815 Act in GB but not in India

The India Packet Letter Act of 1815 was superseded by the Postage Act of 1819 (59 Geo 3 c. 111 dated 12 July 1819; also known as the ‘India Letter Act’). News of this took many months to reach India. Until then, the Presidency GPOs continued to apply the rules of the 1815 Act, along with its associated rates and handstamps.

Letters arriving in Britain after 12 July 1819 were not in accordance with the new Act. So, for instance, any packet postage paid in India would be disregarded and recipients made to pay the new lower 4d ‘India Letter’ rate (for letters weighing up to 3 oz). Further, handstamps applied apropos the old Act were cancelled by the crutched cross.

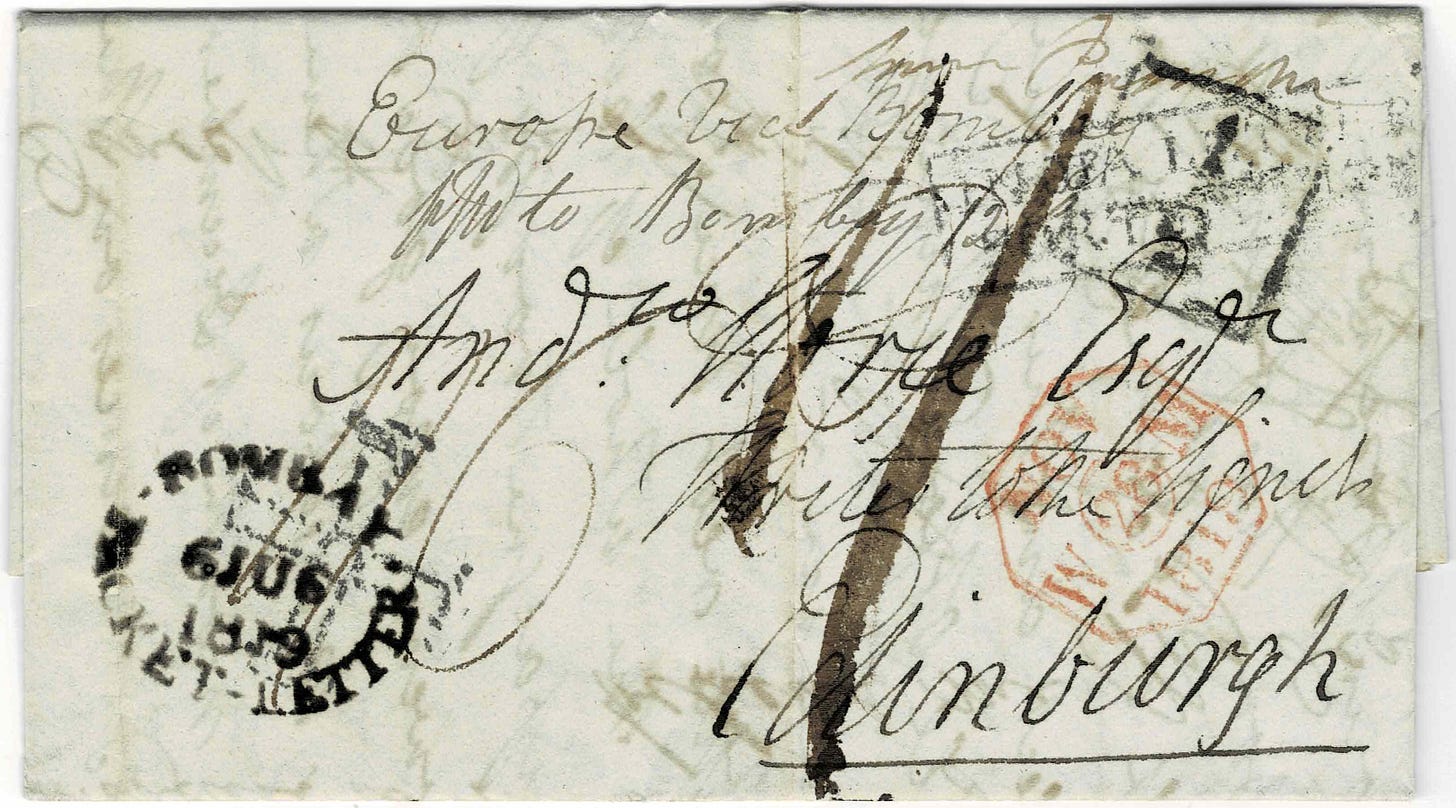

One such example is shown as Figure 4. Written from Hussingabad on 11 May 1819, the letter prepaid 12a for the inland postage to Bombay (see ‘ppd to Bombay 12 as’ third line from top) but did not prepay the packet rate. It was sent to Bombay where it received the ‘BOMBAY PACKET-LETTER’ (Giles SD2) dated 6 June 1819.

On arrival at the London GPO on 25 November 1819, the said mark was cancelled by a crutched cross since the old act’s rules no longer applied. Under the terms of the 1819 Act, postage due of 1s6d i.e. inland postage from Portsmouth to London to Edinburgh of 1s2d single plus incoming ‘India Letter’ rate of 4d per 3 oz was calculated and marked on the letter. Apart from this, the recipient would have also had to pay ½d Scottish Additional Half Penny Tax.

(The contents of the letter are most interesting as it talks about the Third Anglo-Maratha War of 1817-19, which was winding up. “One of the strongest forts in India Asseerghur, has just fallen…Apah the Ex Rajah of Nagpore has found means to conceal himself. I dare say he will never be able to collect another army, a Lac of rupees are still offered him yearly by Govt if he will come in…”)

Another letter, but from Bengal Presidency, is illustrated as Figure 5. For the same reasons as the letter in Figure 4, the double circular ‘CALCUTTA POST NOT PAID’ handstamp was cancelled by a crutched cross; but for some reason, the oval ‘CALCUTTA PACKET LETTER’ mark was not.

Converting Ship Letters into Packet Letters

Since the 1790s, the British Treasury made various efforts to squeeze as much revenue as it could from the Post Office to pay for the government’s ever-increasing expenses especially on account of its never-ending wars. Aiding it was a man with “a perfect craze for high rates of postage”,8 Francis Freeling (Figure 6), the indefatigable Secretary of the Post Office from 1797 until his death in 1836.

The abolition of the East India Company’s monopoly on India trade in 1813 made Indian mails fair game. First came the much-derided ‘obnoxious’ Postage Act of 1814 (54 Geo 3 c. 169 dated 10 October 1814; also known as the ‘Withdrawn Ship Letter Act’). After protests by merchants and amid deteriorating relations with the Company, the 1815 Act was brought in as its replacement just a few months later. It was not much better.9

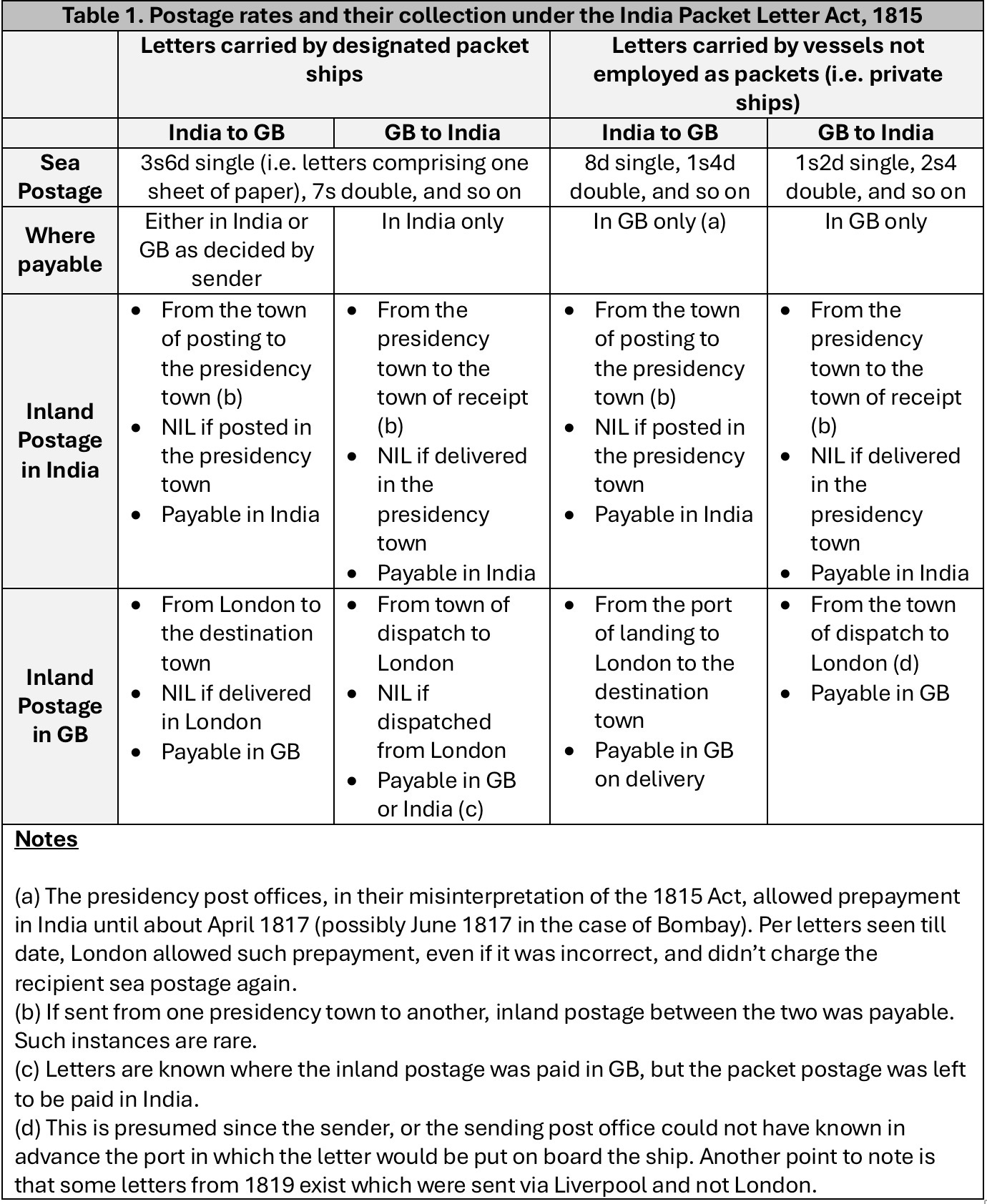

Before we proceed, it may be instructive to tabulate the various charges levied on letters under the 1815 act.

The charges for packet and ship letters were, no doubt, high. What was galling was that the Post Office did not employ regular packets as they did to the Americas or the Mediterranean. Rather, they piggy-backed on either the Royal Navy’s war vessels10 or the Company’s Indiamen11 for sending their so-called packet as well as ship letters. And on many occasions, even private trading ships.12 In this way they saved on the cost of hiring ships specifically for carrying packets; this would have cost anywhere between £1,000-2,000 per trip and would have eaten into the Post Office’s revenues.13

As can be noted from the table, it served the British Post Office well if more letters were carried by packets rather than by private ships since they cost correspondents triple or more: 3s6d packet sea postage vs 1s2d ship sea postage (if sent from GB) / 8d ship postage (if sent from India).

The Post Office had initially hoped that “the Company would permit all their regular & extra Ships to be considered as Packets, like King’s Ships taking Packet Mails, and not Ship Letters Bags.” But, for whatever reasons, the Company decided to alter the arrangement. The Post Office lamented:14

The alteration goes to this - If two or more of the Company’s Ships sail together, one will take a Packet Mail with letters at a rate of Postage of 3/6d each. The other a bag of Ship Letters at a rate of postage of 1/2d each. The ships are equally well found - sail in company - perhaps arrive at the same time - and possibly that with the Ship Letter Bag first - Clamours will be excited, why there should be so great a difference in the Rates of Postage; and it cannot be a satisfactory answer, that one Ship carried a Ship Letter Bag, and the other a Packet Mail - both are under the same Seal of Office and the conveyance equally as good by the other as by the other.

As rightly feared, the public were smart and would not send letters by packets when they could very well send ship letters which cost much less and would reach their destination at more or less the same time.15 In 1818 the Deputy Post Master General at Calcutta wrote to the British Post Office:16

Permit me now to make some Remarks on the Inability of rather Disadvantage of making Packet Mails from India to England, at least from this part of India.

The European Inhabitants of Bengal unanimously object to them, and all the letters that come from far and near are accompanied by Instructions that they are not be sent in a Packet Mail - a reference to all such Packets as have been sent to you from hence will convince you, and they can never prove any Advantage to Government…

In short, the Post Office wanted more revenues but the public would not acquiesce! So, about a couple of years after the 1815 Act had come into effect, the British GPO started resorting to ‘converting’ the designations of ships carrying ship letters to packets, which exasperated Indian correspondents to no end. What follows are some examples.

HCS Marquis of Wellington

A letter dated 8 April 1817 sent by Francis Freeling to the HM Majesty’s Deputy Post Master General at Madras said:

The Packet-Mails are to be encouraged, and the Ship-Letter Mails sent in intervals of Packets, or when in fact it cannot be refused, that is, when the writers mark their letters for particular ships, not intended by you for Packet Mails.

However, the Indian Post Office could not do so since the Court of Directors of the Company had laid down rules for sending mails. Basically, if two or more Indiamen were scheduled to depart from any of the presidency towns, the Deputy Post Master General at that place would ask the Board of Trade to select amongst them at least one as the King’s Packet and the other(s) as non-packets.

Consider the case of letters carried by HCS Marquis of Wellington. In a letter dated 6 January 1818 addressed to the Secretary to the Board of Trade, E.R. Sullivan, His Majesty’s Deputy Post-Master General at Madras, wrote:

I have the honor to request that you will have the goodness, in compliance with the orders from the Hon. the Court of Directors under date 8th May 1816, to select one of the two Indiamen, mentioned in the margin, as a King’s Packet, and authorize the Commander of the other to carry a Ship-Letter Mail for England.

The two ships mentioned in the margin were Marquis of Wellington and Princess Charlotte of Wales.

Having received an answer quickly, Sullivan put out a postal notice dated 7 January 1818 which was published in the Madras Government Gazette of 8 January 1818. It read:

Notice is hereby given, that “a Packet Letter-Mail” will be forwarded to England on the H.C.S. the Princess Charlotte of Wales, - and that a “Ship-Letter Mail” will be transmitted on the H.C.S. ship Marquis of Wellington.

More than a year later, the Madras Courier published a letter to the editor in its 16 March 1819 issue. This letter, dated 15 March 1819, was written by a correspondent under the pseudonym ‘Veritas’ (literally meaning ‘the truth’!) ‘Veritas’ complained:

The Hon. Company’s ship Marquis of Wellington was dispatched from Madras in the month of January 1818, and an advertisement was issued by his Majesty’s Deputy Post-Master General at Madras, declaring the Marquis of Wellington to be a “Ship Letter-mail.” And under this faith, numerous letters were dispatched from the Madras Presidency; but on the arrival in Lombard Street of the letters forwarded by the Marquis of Wellington, the Madras stamp “Ship-Letter” was annulled by a Post-office cross, and the letters stamped de novo, “India Packet-Letter,” and charged with a postage of three shillings and six-pence each.

(The General Post Office was then located at Lombard Street)

The letter goes on to say that a representation was made to Francis Freeling, who replied:

The ship-letter stamp must have been put on the letter through some error at Madras, the Deputy Post-Master General of Calcutta having dispatched the Marquis of Wellington as a regular packet from India, pursuant to the discretion allowed him; and therefore all letters by that ship were liable to the packet-postage.

‘Veritas’ then went on to ask some rhetorical questions. Was the Secretary legally authorised to annual an act of his Deputy, who by official advertisement, invited the public to send letters by a private ship? Was it within the remit of the Post-Master General in England to alter the denomination of letters received as ship letters at Madras to packet letters in England?

While printing the letter, the editor of the Madras Courier sympathised with the writer and slammed the “tricks practiced in the Post-Office of Lombard Street, in regard to Indian correspondence.” He said that he would forward copies of the letter to the Lords the Post-Masters General, and to the Bengal and English editors.

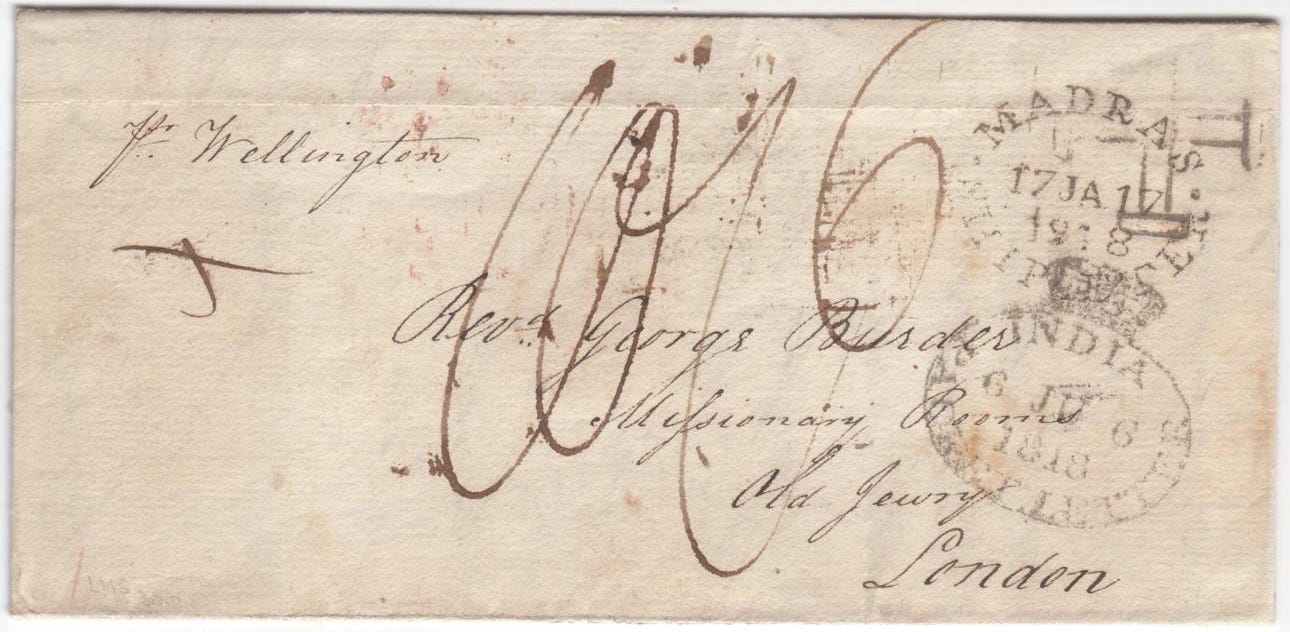

Figure 7 illustrates a letter from Madras carried by the said HCS Marquis of Wellington. Since this ship was advertised as carrying ship letters, the oval ‘MADRAS SHIP LETTER’ mark dated 17 January 1818 was correctly applied. But when the 586 letters carried by this Indiaman arrived at GB in June 1818, the London GPO, seemingly on a whim, changed the ship’s designation to a packet.

The Madras Ship Letter stamp was therefore cancelled by a crutched cross and an oval ‘INDIA PACKET LETTER’ marked. Since this was a triple letter, postage due of 10s6d (or three times 3s6d) was collected from the recipient. No inland postage was levied since the delivery was in London.

If the letter were a ship letter, postage due would have been only 2s (three times 8d) plus inland postage from the port at which the letter was offloaded.

HCS Rose

A similar advertisement to the one above was issued by Sullivan a few days later on 12 January 1818; it was printed in the Government Gazette of 15 January.

Notice is hereby given, that a “Packet Letter Mail” will be forwarded to England on the H.C. ship Minerva; and that a “Ship Letter Mail” will be transmitted on the H.C. ship Rose.

The selection of which ship carried packet mails, and which carried ship letters was, as usual, made by the Board of Trade.

Like in the case of Wellington, when the 970 letters carried by HCS Rose reached London, their Ship Letter marks were cancelled by a crutched cross since the London GPO determined them to be packet letters. Figure 8 shows one example. Total postage for this single letter was calculated as 4s7d i.e. packet postage of 3s6d plus inland postage from London to Edinburgh of 1s1d. If the letter were treated as a ship letter, postage would have been much lower at 1s2d plus inland postage from the port of landing to London to Edinburgh.

Private Ship Ajax

Letters travelling in the opposite direction i.e. from GB to India on the free trader Ajax were subject to the same kind of perversion.

Another correspondent, ‘A Subscriber’, possibly ‘Veritas’ himself, writing to the editor of Madras Courier on 21 March 1819, said:

A public notice was issued at the General Post Office in London, on the 14th July 1818, stating, “that the Ship-Letter Office would dispatch letters for Madras under the regulations of the Acts of Parliament, by the Ajax free trader, to sail about the 20th July 1818.” On the 7th August, the public notice was altered, and the said ship Ajax, “a Ship-Letter Mail,” was converted into a “Packet Mail,” and the letters that had been previously received and stamped “India Ship Letter,” at the rate of 1s.2d. per single letter, were re-stamped with the appellation of “India Packet Letter,” and the rate of postage altered from 1s.2d. to 3s6.

‘A Subscriber’ wondered if changing the denomination of the ship conveyance as well as the rate of postage was legal? He thought if not illegal, it was at least a breach of faith. The editor of the Courier agreed that “it was clearly illegal and a breach of faith with the public, to receive letters for the Ajax as “Ship Letters,” and afterwards re-stamp and new charge them.”

Figure 9 illustrates a letter carried by the Ajax. Initially considered to be a ship letter and stamped with the ‘INDIA SHIP LETTER’ dated 18 July? 1818, the Ajax was, seemingly arbitrarily, re-designated as a packet. The Ship Letter mark was cancelled by a crutched cross and a ‘INDIA PACKET LETTER’ dated 13 August 1818 applied. Postage to be collected in India was changed from the 1s2d to 3s6d. No inland postage was due since the letter was posted in London.

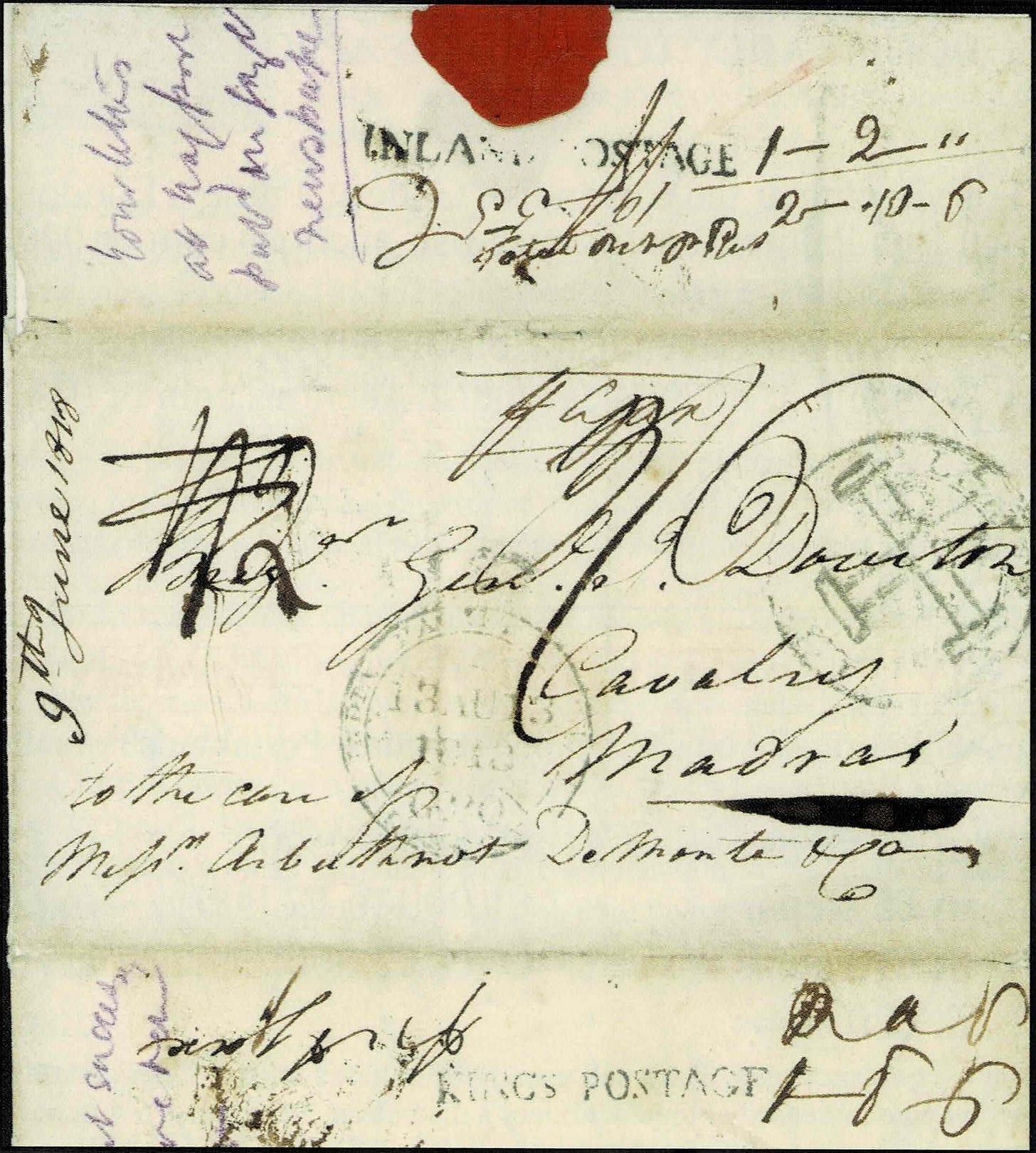

When the letter arrived at Madras GPO, two separate handstamps ‘KING’S POSTAGE’ and ‘INLAND POSTAGE’ were applied on it (Giles SR1).

Against the former, ‘Rap / 1-8-6’ for 1r8a6p (equivalent of 3s6d) was noted. Remember that Madras Post Office had changed its currency from fanams and cash to annas and pies with effect from early 1818. Nevertheless, a manuscript ‘19f55c’ for 19 fanams 55 cash (again equivalent to 3s6d) can also be seen.

Against the latter, ‘‘1-2-,,’’ i.e. 1r2a was mentioned, which was the inland postage of 1r2a from Madras to somewhere in the heart of the country (between 800 and 900 miles per 1799 Madras presidency rates).

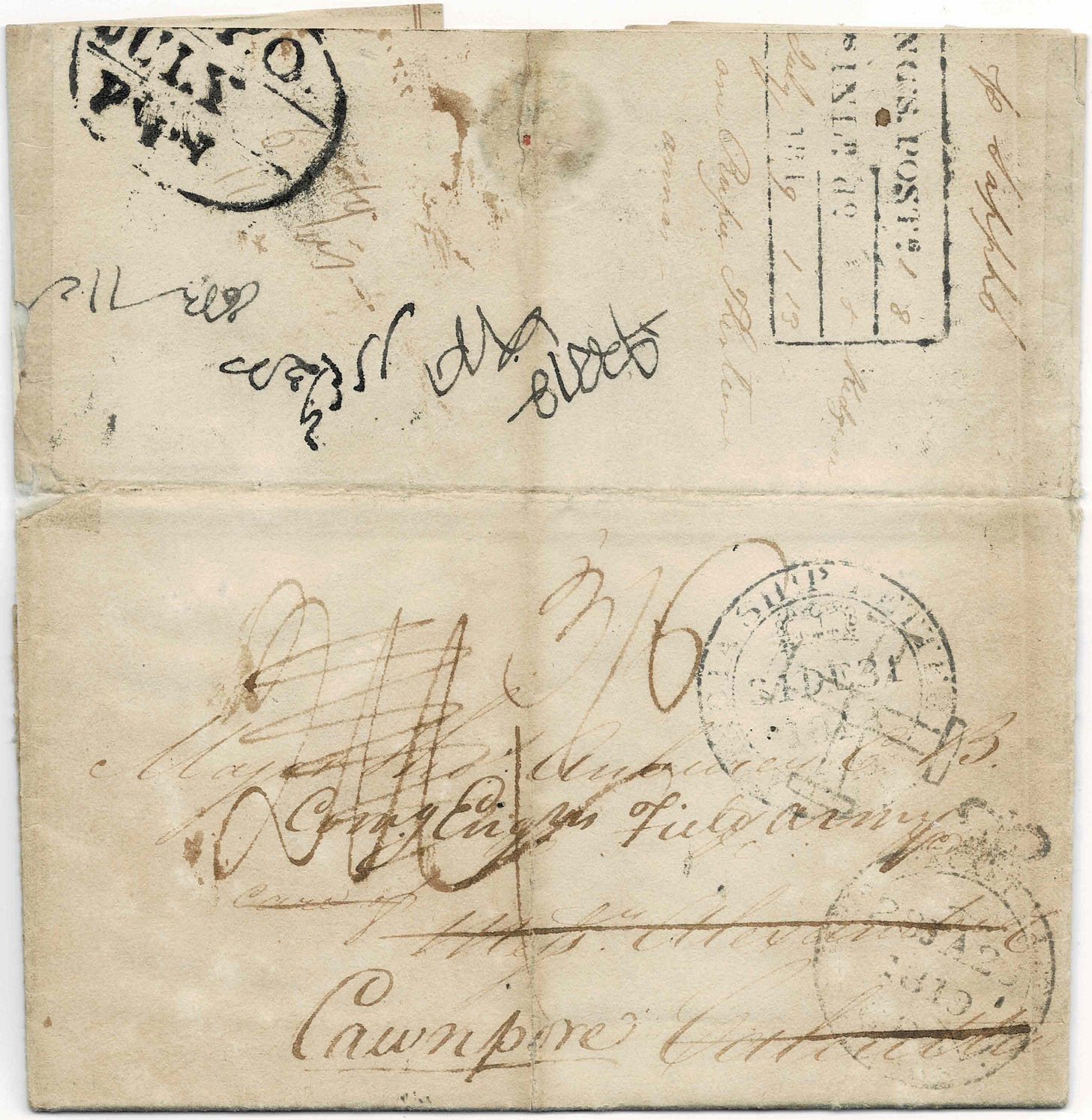

Private Ship Sappho

A letter carried by the Sappho (see top flap right ‘p Sappho’) from GB to Calcutta was subject to the same treatment as the Ajax (Figure 10). It was first considered as double ship letter as evidenced by the ‘INDIA SHIP LETTER’ dated 31 December 1818 and postage due of 2s4d. Almost a month later, on 28 January 1819, the Ship Letter mark was cancelled by a crutched cross and the rate struck off. The ‘INDIA PACKET LETTER’ applied and strangely, the letter was now assessed as a single and 3s6d noted.

Revenues or Schedules?

In the four cases discussed, two incoming and two outgoing, ship letters were converted into packet letters by the London GPO. With reference to the two incoming letters, it is hard to give the benefit of doubt to the British Post Office; it seems plain that they played mischief. While their appointed HM Deputy Post Master General at Madras designated certain ships as carrying ship letters, the London GPO ignored him and decided to rake in some more money.

On the other hand, with respect to the two outgoing letters to India, an argument can be put forth that the change was incidental. If the sailings of the Ajax and Sappho resulted in extra revenues for the Post Office, it was just a happy coincidence and not due to malice.

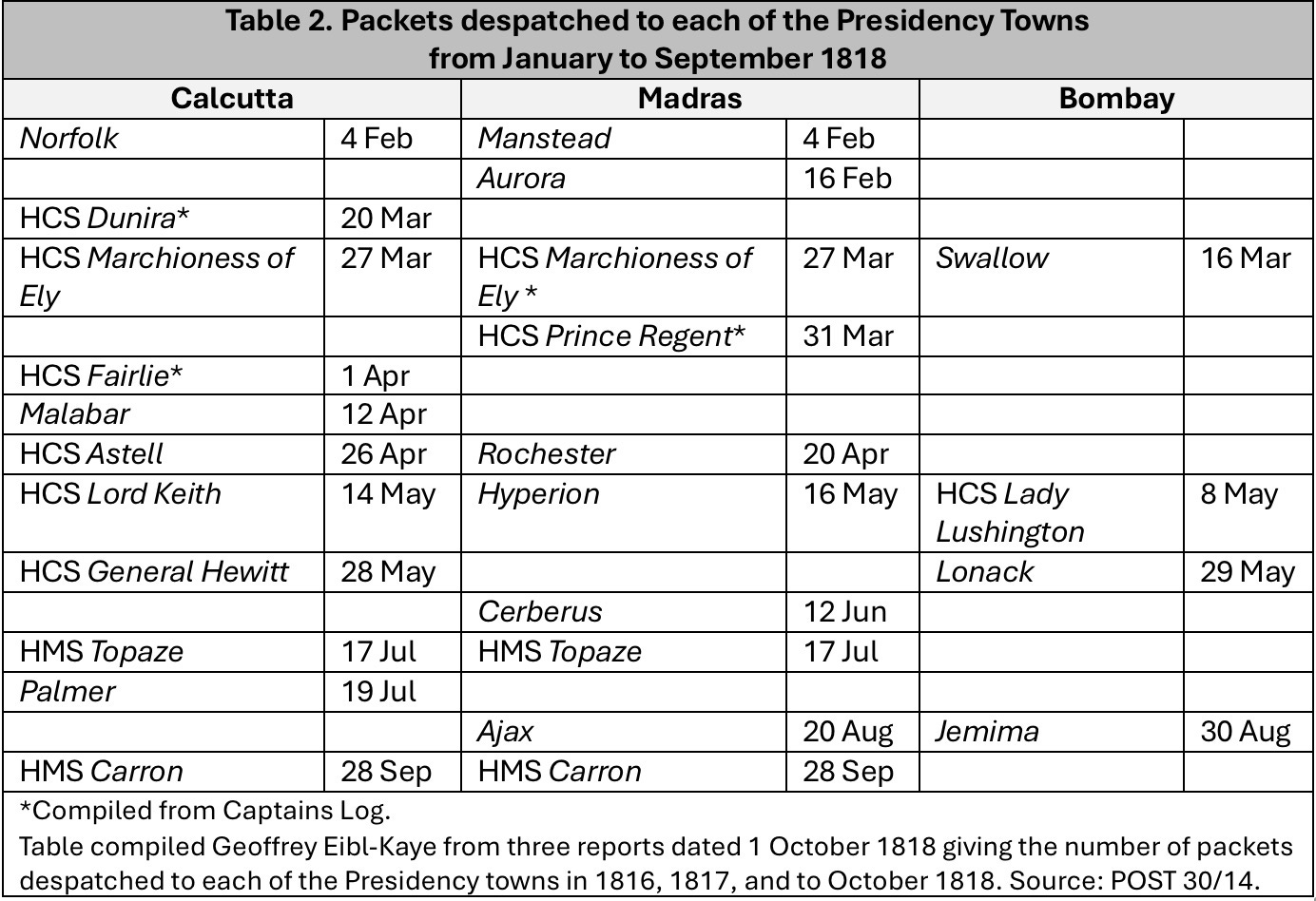

The argument is this. The British Post Office tried to send one packet mail to the two principal presidency towns i.e. Calcutta and Madras every month; lesser to Bombay since there was much less “Commercial Intercourse” and “fewer opportunities to engage Vessels as Packets”.17 A list of packets sent to each of the Presidency Towns in the nine months of 1818 is shown in Table 2. The last packet dispatched to Madras before the Ajax was HMS Topaze on 17 July 1818. While HMS Carron was to have sailed in August directly for Bengal (and letters for Madras sent overland from Calcutta), it was detained by the government and finally sailed only on 28 September. In short, reasons to do with scheduling i.e. the necessity of sending a packet out in August 1818 and none save the private ship Ajax being available, could have behind the change in the Ajax’s designation.

A similar reason could have been behind the Sappho becoming a packet ship. The last packet sent to Calcutta was probably sent in November,18 and there was a need to send another out in January 1819.

However, given the track record of the British Post Office ever since the 1814 Act, one cannot consider this ‘scheduling’ rationale without a pinch of salt. After all, there were months (for instance, March, May, June, and December 1816; November 1817; January 1818) when no packets were dispatched to Madras. In addition, there was nothing in the Act which compelled the Post Office to send out one every month.19

As time went by, the Post Office’s and specifically Freeling’s enthusiasm for operating packets to and from India diminished substantially.20 The public and press had anyway loathed the arrangement since its introduction. The 1815 Act was superseded by a more reasonable Postage Act which was passed by Parliament in July 1819.

Acknowledgements: Geoffrey Eibl-Kaye for graciously sharing his research done at the Post Office Archives and India Office Records at the British Library; limitations of distance and cost would have made it impossible for me to do so. And for his feedback to my draft. Max Smith and Martin Hosselmann for their valuable comments as usual.

References

(A Clerk). “To the Editor of the Asiatic Journal.” The Asiatic Journal for March, 1820 IX (March 1820): 217-227

Eibl-Kaye, Geoffrey. “The India Mails 1814 to 1819 (Part 1). Negotiations between the Post Office and the East India Company.” The London Philatelist 113 whole no. 1314 (April 2004): 78-93

———. “The India Mails 1814 to 1819 (Part 2). Administration of the Packet Service and its Demise” The London Philatelist 113 whole no. 1315 (May 2004): 113-124

Giles, Hammond. “The “King’s Post”, 1815-1819.” India Post 12 no. 1 whole no. 55 (January-March 1978): 15-18

Giles, D. Hammond. 1989. Catalogue of the Handstruck Postage Stamps of India. London: Christie’s Robson Lowe.

Jay, Barrie. 2005. The British County Catalogue of Postal History Volume 3 - London. 2nd ed. Vol. 3. 5 vols. London: London Postal History Group.

Joyce, Herbert. A History of the Post Office from its Establishment down to 1836. London: Richard Bentley & Son, 1893.

Smith, Max. “The Development of the Post in Bombay. Part 4: The Overland Post.” India Post 29 no. X whole no. 125 (1996): 82-87

———. “The ‘Obnoxious Ship Letter Act of 1814.” India Post 50 no. 4 whole no. 201 (October-December 2016): 143-160

Jay (2005, p.172) gives the crutched cross in black a catalogue number ‘L1330’ and mentions the years of usage as 1817-23. The crutched cross in red is recorded as ‘L1330a’ and usage between 1826 and 1840. Jay, in partnership with Martin Willcocks, another famed British philatelist, brought out the five-volume ‘The British County Catalogue of Postal History’. Volumes 1 & 2 (as a single book) and volume 3 (which covers London) saw second editions in 1996 and 2005 respectively.

While Calcutta and Madras did apply ship letter stamps, they made them locally. Calcutta used the octagonal ‘KING’S. SEA / POSTE. PAID. / CALCUTTA’ (Giles SD5), initially for a few months in black and then in red. The mark is very different from the oval ‘CALCUTTA PACKET LETTER’ (Giles SD7) handstamp sent out from GB. It makes one believe that the former was manufactured locally.

Madras used an oval ‘MADRAS SHIP LETER’ (Giles SD6, note one ‘T’ missing) from 1816 to 1819 and then a corrected ‘MADRAS / SHIP LETTER’ (Giles SD7) from May 1819 to early 1820. While both do look very similar to the oval ‘MADRAS PACKET LETTER’ (Giles SD5), the error in the handstamp used for about three years is evidence that it was not manufactured in and sent from GB.

The clincher is a letter dated 17 June 1817 from London Post Office to the Madras Deputy Post Master General stating: “My letter of the 26th October last explicitly told you, that under the new Act you had no operation to perform with Ship Letters for England, although there is no objection to your causing such as you collect to be properly packed and addressed to this Office; therefore there is no necessity to send you out a stamp for Madras Ship Letters.” (The Asiatic Journal, March 1820, p.219).

Clause XVIII of the 1815 Act read: “…That it shall and may be lawful to and for the Postmaster General in his Discretion, to establish Post Offices, and appoint Deputy Postmasters and other Officers, for the due Execution of this Act, in the United Kingdom, and in any of the Presidencies of the said United Company…and that all such Persons so to be appointed shall give Security to the Satisfaction of the Postmaster General or his Agents for the due Discharge of their respective Duties, and accounting for and paying unto the Treasurers of the said United Company, at their respective Presidencies, on account of the Revenue of the Post Office, all Sums which they shall respectively receive for the Port of Letters and Packets, or in any other manner whatsoever…”

The ‘United Company’ being talked about is the ‘United Company of Merchants of England trading to The East Indies’, in short the East India Company.

Clause XVI of the Act said: “…That for the Port and Conveyance of all and every the Letters and Packets that shall be carried or conveyed by Vessels not employed as Packets from The Cape of Good Hope, The Mauritius and The East Indies, to Great Britain, there shall be charged and payable a Sea Postage of Eight pence for each Single Letter, and so in Proportion for Packets.”

On the other hand, clause XLV stated: “…That the Rates of Postage hereinbefore mentioned for the Conveyance of Letters and Packets by the said Packet Boats, Ships or Vessels from any Port in Great Britain, to any in The East Indies, shall be received by the Deputies of the Postmaster General, upon their Delivery in India, and that the Rates of Postage for the Conveyance of Letters from any Port or Place in The East Indies to Great Britain shall be received at the Option of the Parties sending the same, or upon their Delivery in Great Britain or Ireland, by the Deputies of the Postmaster General in India upon forwarding the same.”

So the former implies that postage on ship letters will be charged in GB while the latter makes it optional. Hence, one really cannot blame the Indian Post Offices for interpreting the act with respect to payment of ship postage in the way they did.

This letter of Francis Freeling is dated 28 October 1816 and would have been sent to Presidency Post Offices once London GPO noticed the prepayment of ship letter postage on the first letters sent out from India under the terms of the 1815 act. Consequently, Madras GPO issued a notice dated 15 April 1817 mentioning that ship letter postage of 8d single could not be prepaid. A similar notice issued by Calcutta GPO has not been seen but Giles (1978, p.16) thought that it too would have been dated sometime in April. And the earliest notice issued by Bombay GPO that has been found is dated 20 June 1817.

Calcutta and Madras allowed prepayment of ship letters at 8d single whereas, basis evidence of this letter, Bombay charged 1s2d single. In fact, the 1s2d rate was for ship letters from GB to India and not the other way around.

Giles (1978, p.16) believed that only the Bombay Post Office interpreted the 1815 Act correctly and did not allow prepayment on ship letters in India. He was correct in most matters of Indian postal history; but in this instance he was not. A postal notice issued by Bombay GPO on 30 April 1816 said, among other things: “It is optional for persons sending Letters and Newspapers from India to England, whether by Regular Packets or by Private Ships, to pay the Sea or King’s Postage on them here.” Further evidence that Bombay allowed prepayment of ship postage is supplied by this (and other similar) letters. In short, all three Presidency Post Offices allowed prepayment until about April 1817.

Joyce (1893) devotes an entire chapter to Francis Freeling and his influence on the Post Office. He slams the institution’s “heavy and capricious charges, its high-handed proceedings, its disregard of the public requirements, its prosecutions, its constant indictment of roads which it largely used and yet contributed nothing to maintain, and, above all, the fact that its administration was virtually in the hands of one man, and that man not the nominal head, who could be reached by constitutional means…”

The single best introduction to the 1814 Act and the postal history associated with it is Max Smith’s 2016 article in India Post. Eibl-Kaye’s 2004 two-part Tapling Award winning article in The London Philatelist on the 1814 and the 1815 Acts gives detailed and fascinating information on the happenings behind the scene.

The advantage to the British Post Office in using the navy’s war vessels was that mails could be conveyed without expense. However, the disadvantages were that the navy’s ships left port at their convenience and not that of correspondents, that they did not necessarily touch at all the ports required by the Post Office, and that they did not always remain for a certain time at the ports with the object of bringing mails back home (Memorandum dated 17 February 1816 from Francis Freeling, Secretary to the Post Office, to the Postmaster General; POST 30/14, where POST refers to Post Office Archives and 30/14 to the shelf marks to records in the archives).

The first few mails to India were sent by Royal Navy and private ships. In March 1816, the British Post Office reached an agreement with the East India Company wherein the latter’s Indiamen would carry letters from and to GB.

Clause VI of the Indian Packet Letter Act of 1815 stated: “Provided always, and be it further enacted, That it shall and may be lawful for the Postmaster General, whenever the Ships of the said United Company, or any Private Ships, are employed as Packets, to pay the said United Company, and the Owners of any such Private Ships, for the Freight or Conveyance of any such Mails of Letters, such reasonable Sum, and in such manner, as shall be authorized and directed by the Lords of the Treasury, or any Three of them.”

However, the East India Company magnanimously declined to avail themselves of this “reasonable sum” and allowed letters to be carried on their ships free of charge. The Post Office only needed to pay a small gratuity to the commanders of these Indiamen (Letter dated 22 March 1816 from James Cobb, Secretary to the East India Company, to Stephen Rumbold Lushington, Secretary to the Treasury; Post Office Archives 30/14 and 1/27 p.213 and Letter dated 18 October 1816 from Francis Freeling, Secretary to the Post Office, to Stephen Rumbold Lushington, Secretary to the Treasury; POST 30/14).

As per the above-mentioned letter of 18 October 1816, the Post Office paid the owners of private vessels about £100-150 for each mail.

“There is great difficulty in obtaining any Tenders of private Ships for this purpose - The sum of £500 given to the first was small beyond any expectation - the only other tenders received by us have been £1,000, £1,050 - and in one case £2,000” (Memorandum dated 17 February 1816 from Francis Freeling, Secretary to the Post Office, to the Postmaster General; POST 30/14).

Letter dated 7 January 1817 from the Post Office to the Chancellor of the Exchequer; POST 30/14.

For example, when the first mails on the Company’s ships were dispatched from Calcutta, HCS Prince Regent was designated as a packet and HCS Phoenix as a private ship. The packet mails contained 1,605 letters of which about 700 were Soldiers’ and Seamen’s at 1d each and the postage amounted to £318-0-10. On the other hand, the ship letter mails contained 793 letters, very nearly the same as the packet mails excluding Soldiers’ and Seamen’s, but the postage totalled just £43-6-0 (Letter dated 6 May 1817 from Francis Freeling, Secretary to the Post Office, to the Postmaster General; POST 30/14 XVIII).

Mentioned in a note dated 4 November 1818 drawn up by the Post Office (POST 30/14).

Memo dated 21 November 1817 by Francis Freeling (POST 30/14).

A Post Office memo from mid-November 1818 mentioned that the last packet for Calcutta sailed on 21 October and there was one in the Downs ready to sail (Memo on Indian Packets dated 19 November 1818; POST 30/14). Further, perusing contemporary newspapers, I have not found any mention of any packet having sailed to Calcutta in December 1818. Note that the Company’s ships left Britain for India only during the season, which generally ran from about January to June.

Clause VII of the 1815 Act read: “…a Mail shall be made up and dispatched to India once in every Month, as far as may be found practicable, either by the Vessels to be established and hired by the Postmaster General under the Authority of this Act, or by a Ship of War, or a Ship in the Service of the East India Company, or by a Ship employed in the Private Trade to and from India.”

In a letter dated 19 November 1818 sent to the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Nicholas Vansittart, Francis Freeling transmitted for the former’s perusal “the East India Papers”. He says that “they set forth the manner in which the Act has been Executed - they show the difficulties of executing it, the inconsistencies of part of the Act, & prejudices entertained, particularly in India, against the whole.” He also mentions: “I hear from good authority that certainly some attempt will be made early in Parliament to get the Act repealed.”