The TV series, Shōgun, based on the 1975 novel by James Clavell, has led to renewed interest in Japan, its culture, and its history especially its interaction with the western world. Having devoured it (the last episode came out on 23 April) and coincidentally receiving an interesting item of postal history recently, I thought of combining history, postal history, and social history in one post. Feedback is welcome and can be sent to abbh [at] hotmail.com.

The first westerners to arrive in Japan were António Mota and Francisco Zeimoto in 1543. They were Portuguese traders on board a Chinese merchant junk on way to the Chinese port of Ningbo. After being blown off course, they arrived on Tanegashima, an island in south-west Japan.

Eager to establish trade with the country, the Portuguese established formal traffic through the port of Nagasaki in south-west Japan. Other Europeans soon followed thereafter (one of whom was William Adams, the first Englishman to reach the country in 1600; John Blackthorne, the character in Shōgun is loosely based on him). They brought with them new trade ideas and gun powder weaponry. And Christianity, of course.

In 1603, Tokugawa Ieyasu (Figure 2) (the character, Lord Yoshi Toranaga, is largely based on him) established the third and last shogunate - government of the shogun or hereditary military dictator - headquartered in Edo (now Tokyo). For more than 250 years until late 1867, the Edo shogunate was the most powerful central government Japan had yet seen. It controlled the emperor,1 the daimyo (feudal lords), and the religious establishments, and handled Japanese foreign affairs.

For various reasons, Japanese foreign policy began to turn inwards. Popularly known as sakoku, a series of edicts issued by the shogun between 1633 and 1639, led to Japan entering an extended period of self-isolation. Christianity was banned (there were an estimated 215,000 Japanese Christians by the 1590s), Japanese people were prohibited from making or returning from trips overseas, Europeans were expelled (the Portuguese in 1639), and directives restricted foreign trade with various countries. The Dutch became the only Europeans allowed to remain in Japan, albeit only in Dejima, a small (120m x 75m) artificial island in Nagasaki Bay, where they were kept under close scrutiny.

The isolation was to endure for 200 years until the 1850s. In 1852, Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry was assigned a mission by American President Millard Fillmore to force the opening of Japanese ports to American trade. After some gunboat diplomacy, Perry signed the Treaty of Kanagawa with the Japanese on 31 March 1854 (Figure 3). The treaty opened the ports of Shimoda and Hakodate to American ships and led to the establishment of an American consulate in Shimoda.

Between July and October 1858, Japan signed the Ansei Treaties or the Ansei Five-Power Treaties, the ‘Unequal Treaties’, with five powers: United States, Netherlands, Russia, Great Britain, and France. The treaties opened up more ports to foreigners: Edo, Kobe, Nagasaki, Niigata, and Yokohama (Figure 4).

Attracted by potential trade opportunities, merchants from various European countries landed in Japan. One such was the Prussian Louis Kniffler who arrived in Nagasaki in January 1859.

The Letter

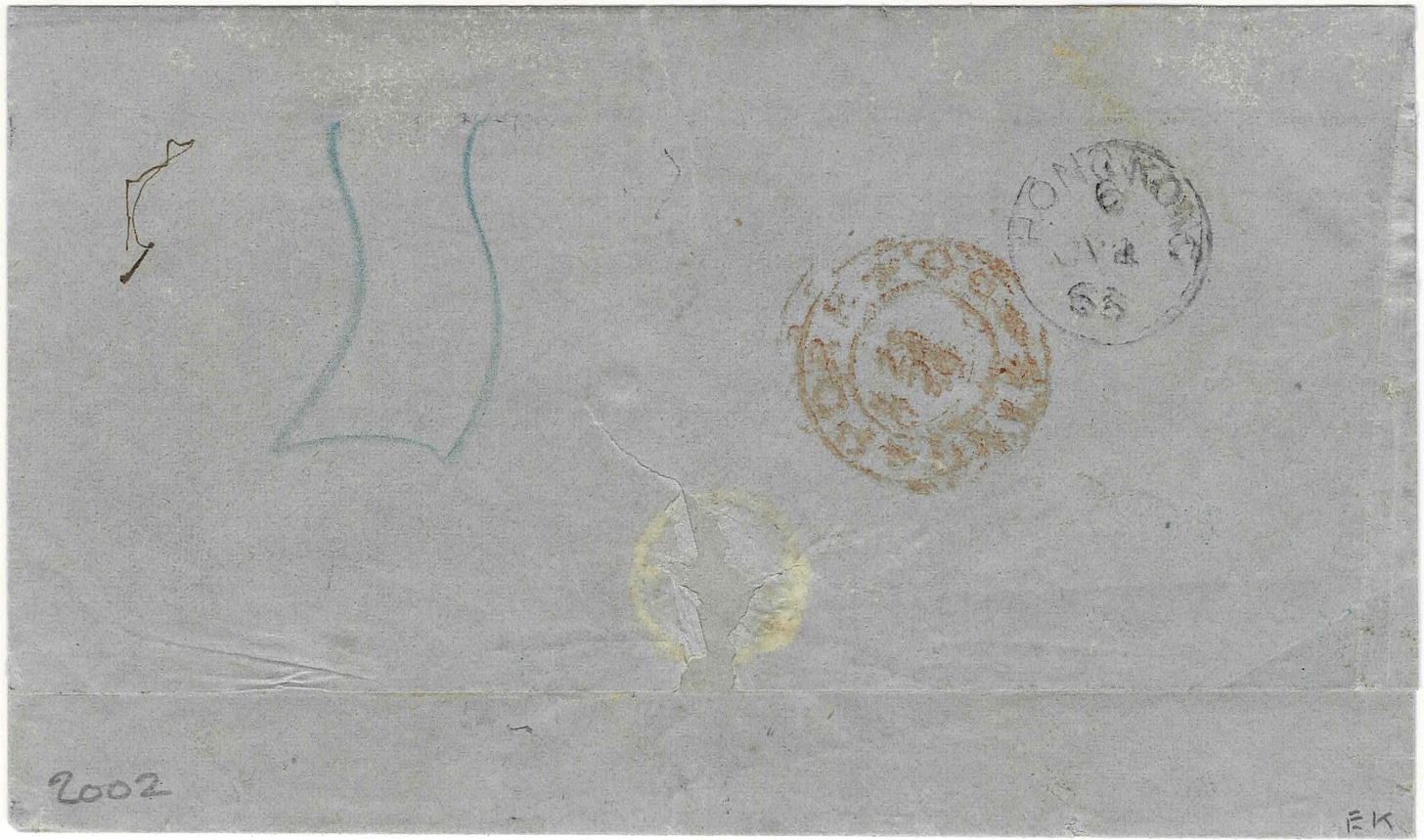

Figure 5 shows the front and back of a letter from Batavia, Dutch East Indies to L. Kniffler & Co. in Yokohama, Japan.

Aspects of Postal History

The letter is datelined 14 June 1866 (recipient’s docketing) and, as evidenced by the Batavia post office stamp on the front, was posted the same day. So, the first interesting aspect is that it is dated to when Japan’s shogunate still existed.

Carried to Singapore on a Dutch East Indies contracted steamer, the NISM Baron Bentinck, the letter arrived on 19 June. The rear shows an indistinct datestamp of the Indian post office at Singapore (2? June 1866).2

The letter was put on board the Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Company’s (P&O) steamer Ganges. At Hong Kong, the mail bag was opened and the letter received a datestamp of 4 July 1866. Until 1868, the General Post Office at Hong Kong was the distribution office for mail to and from the Japanese agencies; from then, the responsibility was taken over by the British post office at Shanghai (Proud 2004, p.1143). This is probably the reason why Kirk (1982, p.197) says that covers prior to 1868 don’t show any datestamps of Shanghai (or Yokohama).

Also marked at Hong Kong was a ‘4’ in red signifying postage due of 4d per half ounce. This charge was introduced in 1844 and was the ship letter rate on mails being carried around the China coast i.e. between Hong Kong, Macao, Chusan, and the five Chinese treaty ports. This charge seems to have been later extended on mails between Hong Kong and the Japanese treaty ports.

From July 1863, P&O started operating steamers between Shanghai and Yokohama, sometimes via Nagasaki - the so-called ‘Japan Line’. The line was an extension of two existing lines i.e. Bombay to Hong Kong via Galle, Penang, and Singapore and Hong Kong to Shanghai. Until December 1867, the line was non-contractual in nature. Hence, when the mail bag containing this letter was put on board the steamer Nepaul at Shanghai, it can be said to have been carried during the ‘experimental’ period of the Japan Line.

Under the terms of the Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Amity and Commerce of 1858, a few Japanese ports were opened to British trade. Consulates were set up at these ports starting with one opened in Kanagawa on 21 July 1859. It was soon relocated across the bay to Yokohama. Postal agencies were also opened at these consulates; the Yokohama consulate provided postal services from 1 July 1860 until a seperate post office was opened in July 1867.

Hence, this letter would have been delivered to the recipient via the British postal agency at the Yokohama consulate.

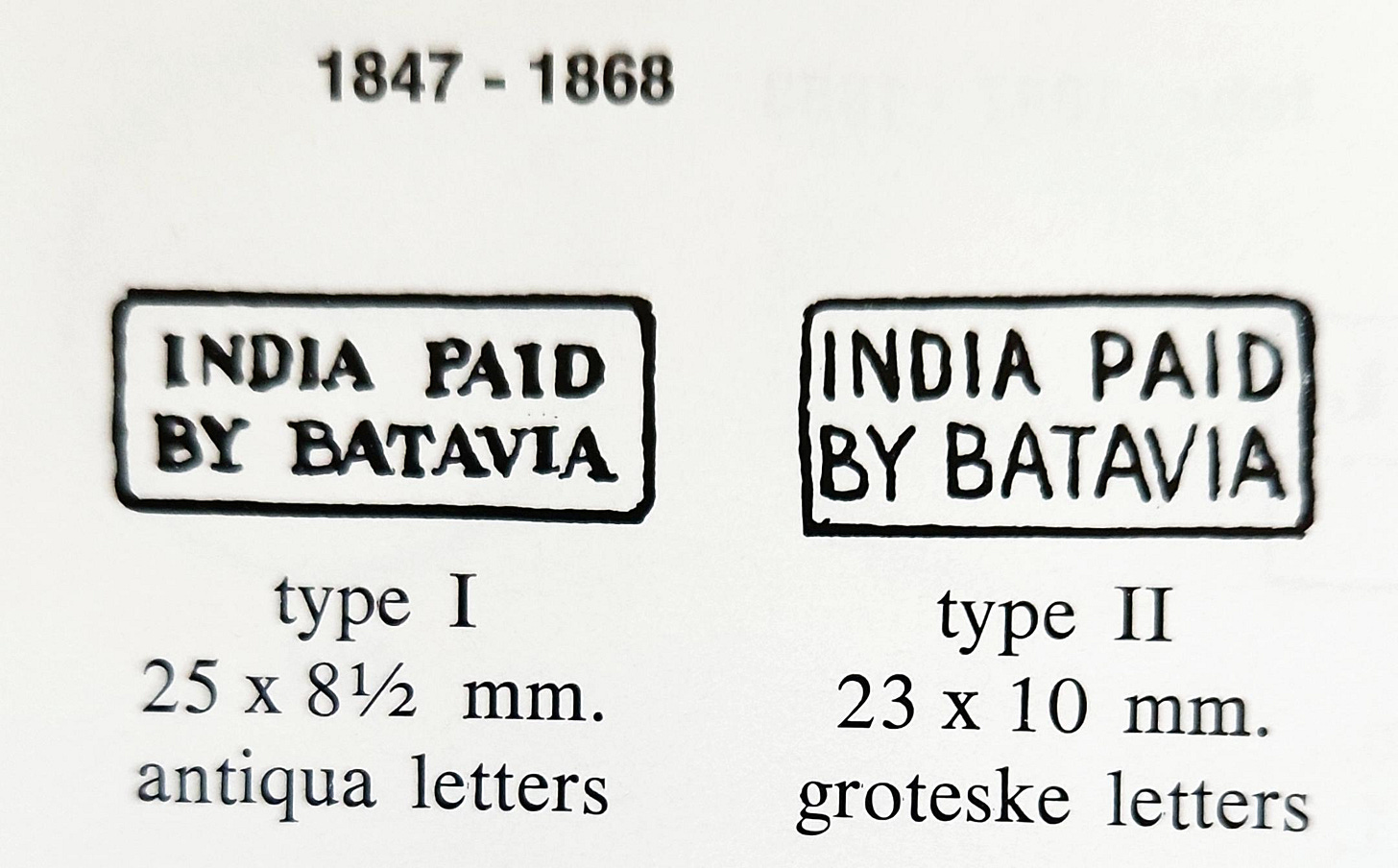

The IP/BB mark

An important postal marking on this letter is the boxed INDIA PAID / BY BATAVIA (type I) (Figure 6) mark which was applied at Batavia. This mark informed the Indian post office at Singapore that all Indian charges had been prepaid in Batavia; in this case it was 55 silver cents (see ‘55’ on rear). It usually, but not always, signified that letters were prepaid to destination. There must have been an agreement between the Batavian and Singapore post offices on the former collecting postage on the latter’s behalf, but that hasn’t been found as yet.

The IP/BB is a strange one. It’s known to be used in 1847 only and then resurrected in 1862 to be used for a few more years. The letter being discussed shows the latest recorded use of IP/BB type I. And a census of covers shows that a few days later, in the same month of June 1866, type II (Figure 6) was introduced.

Finally, it’s the only letter to Japan carrying a IP/BB stamp in private hands.

Louis Kniffler - Pioneering Trader in Japan

The sender of the letter is identified as Pandel & Stiehaus, a German firm operating in Batavia in Dutch East Indies; its blue handstamp can be seen on the front. The company had been established in 1848 by Friedrich Pandel and Georg Friedrich.

The recipient of the letter is Louis Kniffler & Co., one of the first foreign firms to start operating in Japan. It was established in Nagasaki in early 1859 by Louis Kniffler (1827-1888) (Figure 7). Since Prussia wasn’t one of the countries that signed the Ansei Treaties, its citizens weren’t allowed to trade in Japan (an amity and commerce treaty was signed between the two countries in January 1861). However, as Kniffler had spent years in Dutch East Indies and was multilingual, he decided to take a risk; his business in Batavia wasn’t doing well and he wished to make a fresh start. Though the ports of Yokohama, Hakodate, and Nagasaki were scheduled to be opened to international trade from 1 July 1859, he wanted to get a head start and arrived six months early.

Within five years, Kniffler & Co. became the largest German trading firm in Nagasaki. In the 1860s-70s, it began specialising in importing machinery, armaments and capital goods for large-scale infrastructure projects, with a special focus on doing business with the Japanese government.

In 1866, Kniffler returned to Düsseldorf though he continued to handle the branch office of the firm there. The firm was taken over by one of the other partners, Carl Illies Sr. (1840-1910) and its name changed to C. Illies & Co. in 1880. The firm continues to be in business today!3

Archives of Kniffler / Illies & Co.

From the early years of the company, 156 business letters have been preserved in the company archives in Hamburg.

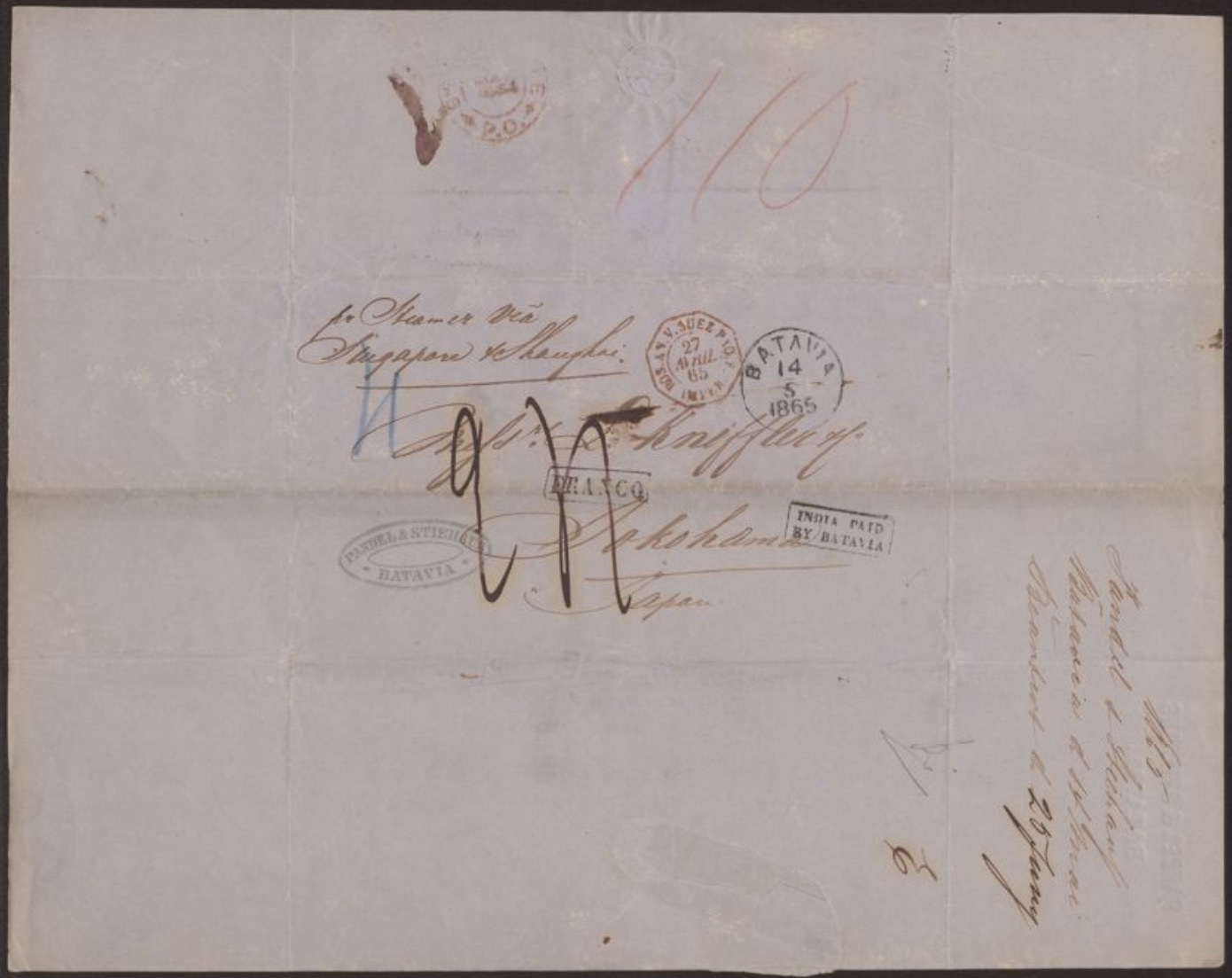

A search of the archive results in 17 letters from Batavia. One, shown as Figure 8, from the same sender, is docketed as being written 14 June 1865 and has the same IP/BB handstamp. This is one other letter to Japan bearing this mark that I know of.4

References

Beer, W. S. Wolff de. De Poststempels in Gebruik in Nederlands Oost-Indië van 1789 tot 1864. The Hague: J. L. Van Dieten, 1971.

Delbeke, Claude J.P. De Nederlandse Scheepspost. I. Nederland - Oost-Indië 1600-1900. Met Catalogues van de Stempels. Aalter, Belgium: The Author, 1998.

Kirk, R. The P&O Lines to the Far East. Vol. 2. 4 vols. British Maritime Postal History. Heathfield, East Sussex: Proud-Bailey Co. Ltd., 1982.

Påhlman, Sven. “India Paid by Batavia.” Filatelie 96 no. 1 (January 2018): 32-34

Påhlman, Sven. “India Paid by Batavia - an Update” Filatelie 96 no. 6-7 (May 2018): 290-291

Proud, Edward B. The Postal History of Hong Kong. Heathfield, East Sussex: Proud-Bailey Co. Ltd., 2004.

Salles, Raymond. La Poste Maritime Française. Tome V. Les Paquebots de L’Extrême-Orient: Saigon - Hong-Kong - Shanghai - Yokohama - Kobe. Vol. V. IX vols. Encyclopédie de la Poste Maritime Française Historique et Catalogue. Paris: The Author, 1966.

Scamp, Lee C. Postal Rate History of China and Hong Kong. The Pre-Adhesive Period to the Beginning of Packet Service from HongKong 1800-1845. Houston?: Nancol Enterprises, Inc. with assistance from the Texas Philatelic Foundation, 1986.

Schmidtpott, Katja. The German trading company L. Kniffler & Co. in Japan, 1859–1880. Working Paper No. 13. Tokyo: Aoyama Gakuin University College of Economics. http://www.econ.aoyama.ac.jp/laboratory/1080.

Webb, F. W. The Philatelic and Postal History of Hong Kong and the Treaty Ports of China and Japan. Reprint. James Bendon Philatelic Series, Four. Limassol, Cyprus: James Bendon, 1991.

Japan’s emperor wielded little power between 1192 and 1867. The opening up of Jaoan led to vast changes in Japan’s political structure. In November 1867, the last Shogun was forced to yield the administration of civil and military affairs to the then emperor Mutsuhito; this political revolution is known as Meiji Restoration.

Post offices in the Straits Settlements (Singapore, Penang, and Malacca) were under the Bengal Presidency’s postal administration from March 1830 to March 1867.

The interested reader is directed to the 33-page working paper on the firm’s early years by Schmidtpott; see references.

This is a puzzling cover and can anyone help clarify? Does the ‘24’ indicate that the letter is from France and was post paid 24 decimes? The French mark POS. AN. V. SUEZ. PAQ. F. / 27 / AVRIL / 65 / IMPER. means the letter was carried by the Messageries Imperiales Impératrice which sailed from Suez (27 April 65) to Hong Kong (29 May 1865) via Singapore; there is a Singapore datestamp of May 1865 (day not seen). But why and how did the letter go to Batavia? And presumably back again to Singapore? Is the Batavia datestamp of 14 May correct? From Singapore, how was it carried to Yokohama?