This article was published as, “A Visit to the Munich Philatelic Library”, Philatelic Literature Review 72 no. 3 Whole no. 280 (Third Quarter 2023). Philatelic Literature Review is the journal of the American Philatelic Research Library.

Translated into German and published as “Ein Besuch der Münchner Philatelistischen Bibliothek”, Phila Historica no. 3 (October 2023). The same issue contains the English version as well.

Further, published as, “A Visit to the Munich Philatelic Library”, The Philatelic Journalistic 174 (July 2024).

The Munich Philatelic Library (MPL) (German: Münchner Philatelistische Bibliothek), holding currently about 65,000 media items1 (Medieneinheiten) in 43 languages,2 is the largest philatelic library on the continent of Europe. It’s also arguably one of the four most important philatelic libraries in the world along with the American Philatelic Research Library (APRL) and the library of the Collector’s Club of New York (CCNY) in the United States and library of the Royal Philatelic Society (RPSL) in the United Kingdom. However, unlike the latter which are privately owned, the MPL is a public library.

The MPL operates as part of the central library of Munich City Library (Münchner Stadtbibliothek). The city (or public) library itself traces its history back to 1843 and has a total stock of around 3 million media items.

History of the MPL

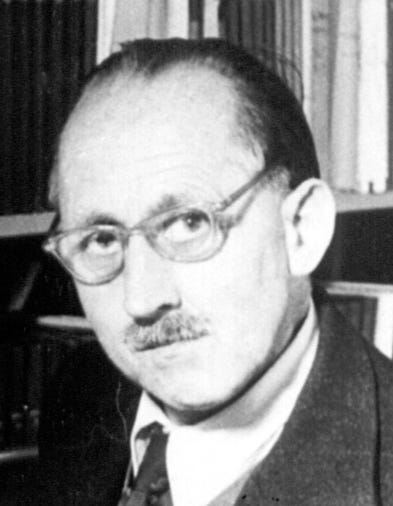

The Munich Philatelic Library, as we know it today, was born in 19313 because of the efforts of one man, Christoph Otto Mueller (1894-1967) (Figure 1).4 A stamp collector from the age of 12,5 Mueller became interested in philatelic literature since at least 1924 when he became the librarian of the Exchange Club of Munich Stamp Collectors (Tauschverbindung Münchner Briefmarkensammler or TAUMA). Soon after, he became the librarian of the Munich Postal Stationery Collectors’ Association (Münchner Ganzsachensammler-Verein or MGSV)6 as well.

Mueller entered the service of Munich city’s municipal department in 1914. After passing through various municipal departments, 1931 saw him working as an administrator in the city’s main cash register. He was then of the opinion that South Germany lacked public libraries for philatelists while North and Central Germany had many, such as the Prussian State Library (Preußische Staatsbibliothek) in Berlin, the University Library (Universitätsbibliothek) and German Library (Deutsche Bücherei) in Leipzig, and the City Library (Stadtbibliothek) in Frankfurt. Therefore, he decided to orchestrate the creation of the MPL as a centralized library of philatelic literature in Munich.

In February 1931, he persuaded art dealer and chairman of the Munich Stamp Club (Münchener Briefmarken-Club),7 Friedrich Heinrich Zinkgraf, to donate his extensive superfluous private holdings. The club itself donated its entire holding of philatelic literature.

Further, TAUMA gave up all but its most indispensable reference books and MGV contributed all literature not relating to postal stationery. Books from the estate of Anselm Larisch, the famed Munich stamp dealer and publisher who had died many decades earlier in 1892, and another dealer named Mühl came in. Last but not the least, Mueller’s own collection was incorporated into what served as the foundation of the MPL.

Mueller also planted the seed of a philatelic literature library in Dr. Hans Ludwig Held (Figure 2), the Munich city library’s head. Held agreed and even allowed it its own premises. Thus, Mueller set up the library in a room in the town hall (Rathaus) of the city on Marienplatz, a central square in Munich.

In the coming years, he succeeded in getting philatelic organizations and private individuals to donate their stocks of literature to the library. For instance, in late 1938 (or early 1939) after negotiations with the Prussian State Library (Preußische Staatsbibliothek) in Berlin, he acquired 30 boxes of literature duplicates that were from the former libraries of distinguished philatelists such as Carl Beck, Alexander Bungerz, and Dr. Otto Rommel, as well as the Berlin Philatelic Club (Berliner Philatelisten-Klub).8 The 1930s also saw the absorption of the libraries of Colonel Hugo Schroeder, the renowned researcher of Bavarian stamps and postal history and Alexander Leo, the Great Britain specialist and former editor of the journal Das Postwertzeichen (The Postage Stamp).

In 1934, Mueller, then holding the post of city inspector, was formally appointed to the Munich Philatelic Library when he was transferred to the public library at Rosental (Volksbibliothek Rosental). But the start of the Second World War saw him go back to his cash register. However, he used his nights, some of which were filled with air raid alerts and bombardments, working on an extensive philatelic literature index filling in thousands of little cards (indexing German journals in the main) and on developing a method of systematization by key words.

Meanwhile, the 5,000 items of the library survived the war unscathed as it was moved to Traunstein in south Germany.

The war years weren’t kind to Mueller. His house was bombed on July 25, 1944, and a couple of months later, his son was killed in action. In addition, after the war, he was sidelined for a couple of years during a period of political housecleaning; he was reinstated in September 1947.

In March 1950, the library moved to Possartstrasse 15, in Bogenhausen, Munich. It was here that Mueller could start indexing the library’s stock in a serious way. Further, his other project – Literatur-Nachrichten (Literature News / Report) – saw its coming of age.

From 1949 to 1963 Mueller was the chairman of the philatelic literature division (Bundesstelle B or Section B) of the Bund Deutscher Philatelisten e.V. (BDPh)9 (Federation of German Philatelists).

In a meeting of this division in 1949, it was decided to assemble and publish information about a “large number of small studies.” Published in book form since January 1951, Literatur-Nachrichten is possibly the world’s largest philatelic bibliography to date, listing a huge number of titles of journal articles in addition to monographs, catalogs, etc. The last printed volume was number 101 covering the year 2001 (published 2004); since then, it is being published electronically.10

Mueller slogged alone for much of his time at the MPL, getting a typist only in 1953! He took early retirement with effect from February 1, 1958; he was then older than 63. Mueller died May 7, 1967.

Mueller was succeeded by chief inspector Dr. Hans Schmeer Walter Merkle (1906-1980) who served as director of the library from 1958 to 1968. Following his retirement, chief inspector Otto Gleixner (1934-2009) (Figure 3) filled the role from March 1969 to March 1997 i.e. for 28 years! Then came Robert Binner (b. 1956) (Figure 4), who took over in 1997 and retired in November 2021 (Figure 4); again, a long tenure of 24 years. It must be noted that all four of them were collectors and philatelists, which would have served the library well.

Since March 2022, the head of the philatelic section has been Joergen (Jörgen; see note 4) Pfeffer.

MPL am Gasteig (at Gasteig)

Until it was integrated with the city library at the Gasteig cultural center11 on Rosenheimer Strasse, 5 (road or street), the MPL always functioned in cramped premises and changing addresses. In 1964, it moved to Sparkesstrasse, 5 and after 1976 to Pestalozzistrasse, 2.

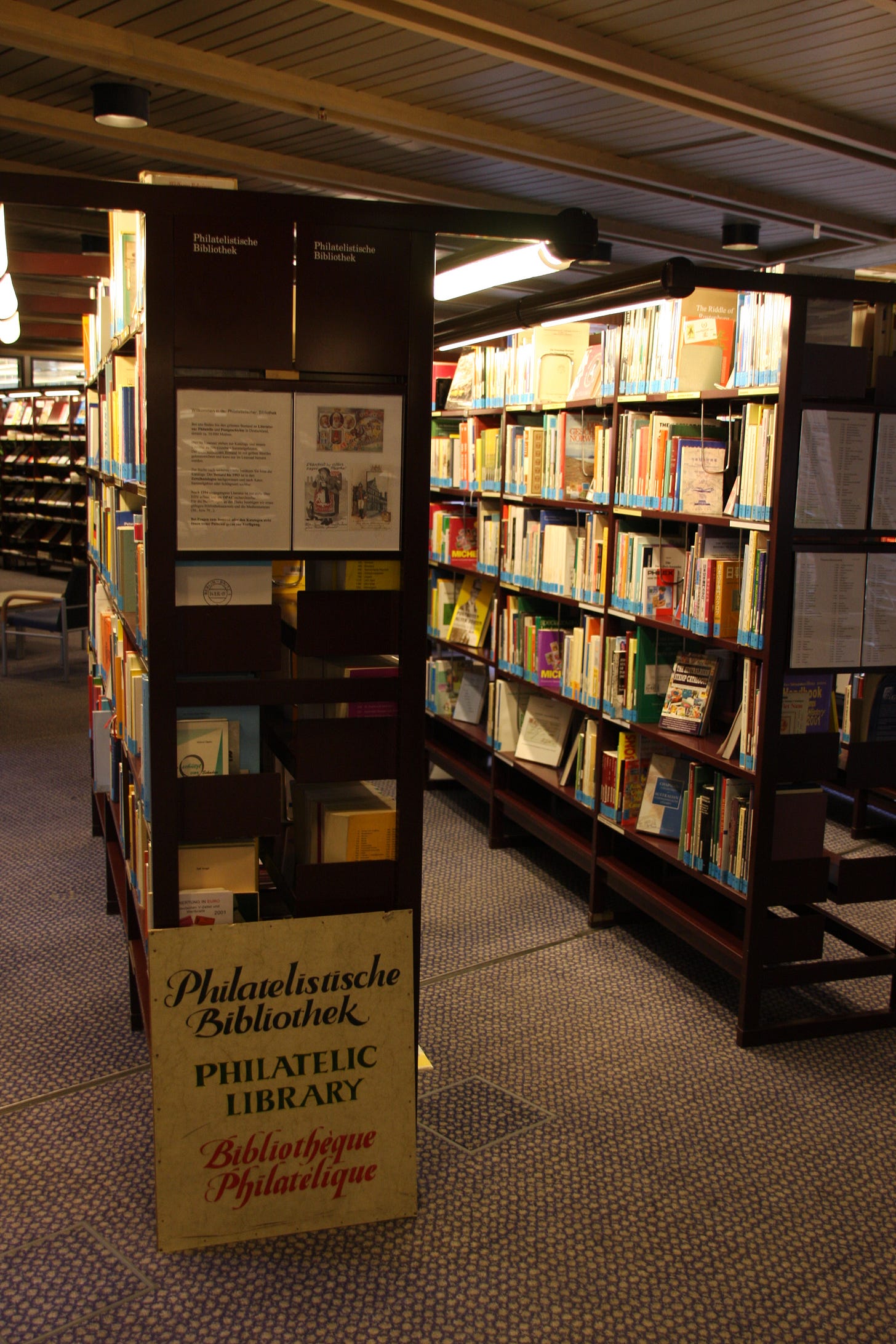

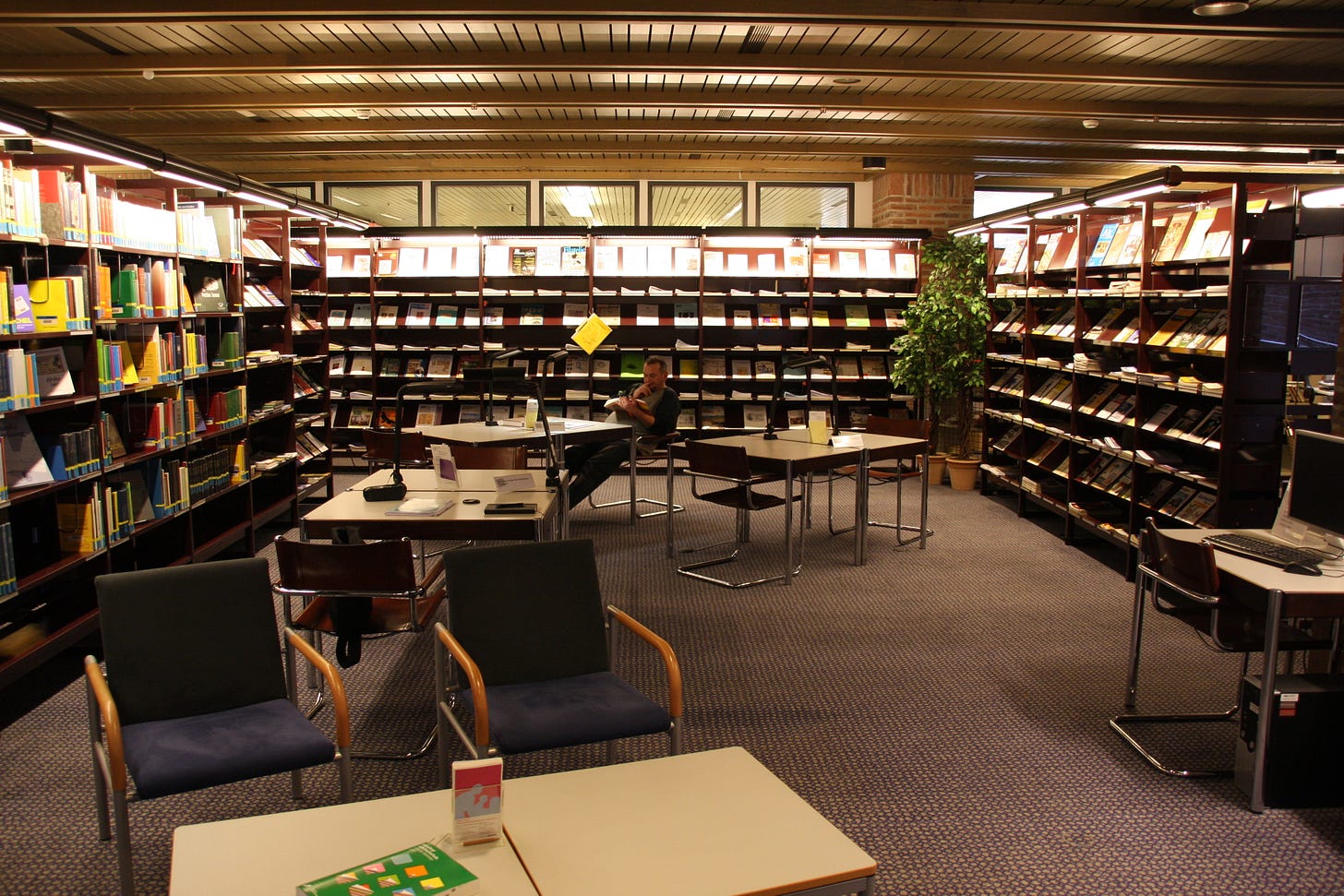

In 1984/1985, the Gasteig (Figure 5) opened, and it was here that the city library (Figure 6) and the philatelic library (Figure 7) found a long-term home.

In this complex, the philatelic library had about 400 feet (120 meters) of shelf space and about 1,950 square feet (180 square meters) for a reading room (Figure 8).

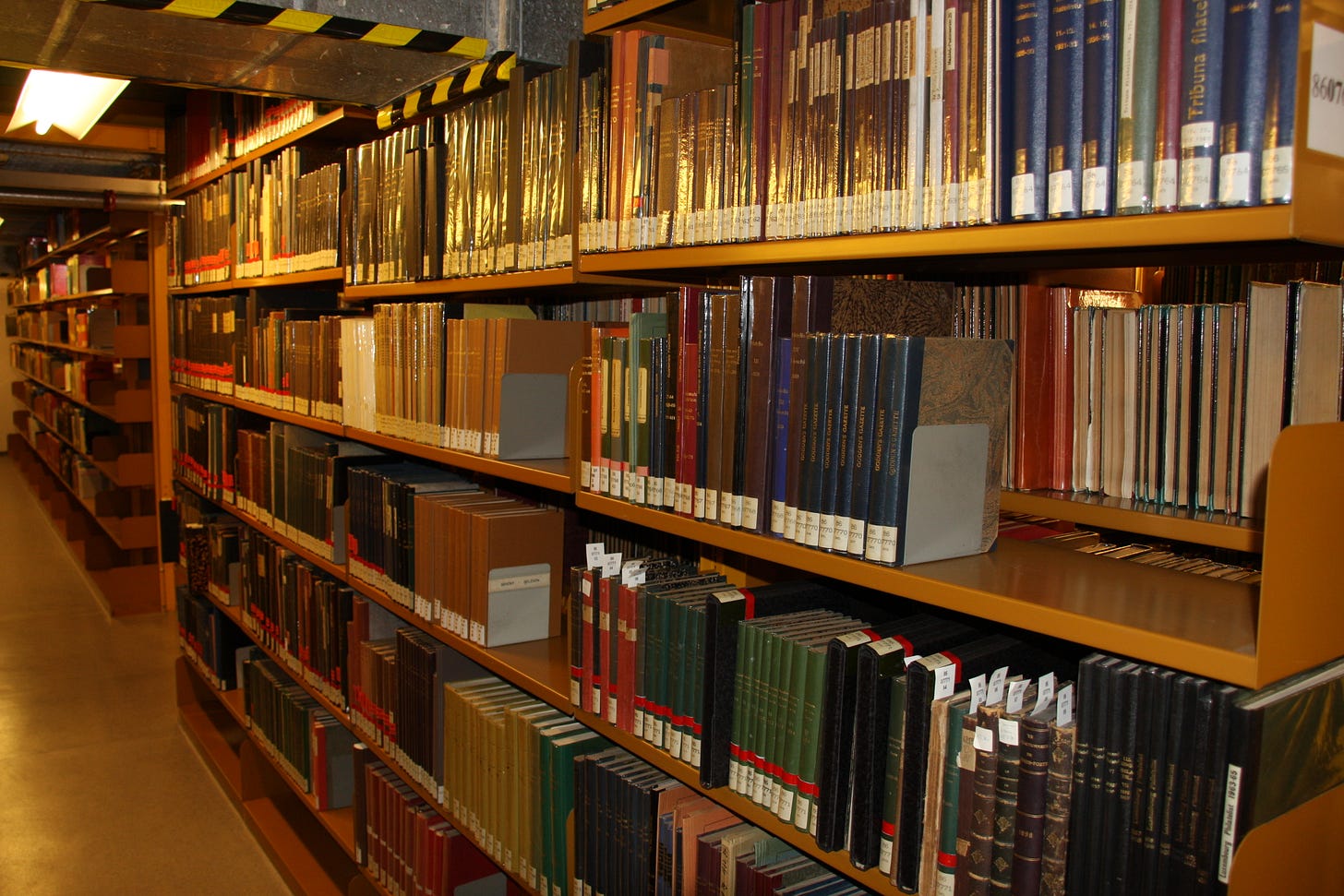

About 5,000 items could be accommodated on the shelves, mostly current books and journals including new catalogs and digital media. The rest of the collection was stored underground in a vast 10,000 square-meter space (Figure 9). While access was limited to library staff, visitors could request desired titles which could be brought up to the reading room through a lift.

First Impressions of MPL im HP8 (in HP8)

In the summer of 2023, I was to go on a family holiday to Germany. As most other philatelists, I was keen on taking the opportunity to do some philatelic sightseeing as well! I emailed the Munich Philatelic Library requesting an appointment. The current librarian and head of the philatelic section, Joergen Pfeffer, was most welcoming and we agreed on a mutually acceptable date and time.

Unfortunately, he also conveyed some bad news. He said that the philatelic section of the city library was in a “pretty awkward situation.” It had to move due to renovations to the Gasteig and the philatelic collections had been split. There also had been radical re-structuring and reduction of staff; from four to just two posts.12 And because of the long-term illness of his colleague, Pfeffer had been working alone since the middle of 2022. Perhaps he wanted to temper my expectations when I came visiting.

Information gleaned from Gasteig’s website and elsewhere indicated that the city library at Gasteig closed its doors on July 31, 2021. Since November 2021, the city library functions in a temporary location called Gasteig HP8 (HP8 stands for ‘Hans-Preissinger-Strasse 8’).13 The reason for the move is the renovation of the complex on Rosenheimer Strasse. To cost no more than 450 million euros, the estimated time frame for completion is about four to five years. However, renovation hasn’t begun due to problems concerning planning, finances, tendering, etc. and it may well take seven years or more.

On the morning of June 12, I took a train going in the opposite direction and reached Gasteig HP8 (Figure 10) a few minutes late (being in Germany, I was a bit apprehensive at this faux pas!) I made my way to the second floor of Halle E (formerly, an electric transformer hall) where the MPL is currently located where I found Pfeffer waiting for me.

Pfeffer (Figure 11), 49, is a trained librarian holding a Master of Librarian and Information Service degree. He has been working in the MPL since October 2014. Earlier, he was in the special library of a research institute occupied with basic research on medieval history that was housed in the building of the Bavarian State Library (Bayerische Staatsbibliothek).

Unlike his predecessors, Pfeffer isn’t a philatelist or postal historian. But then, his predecessors didn’t have a degree in library science either!

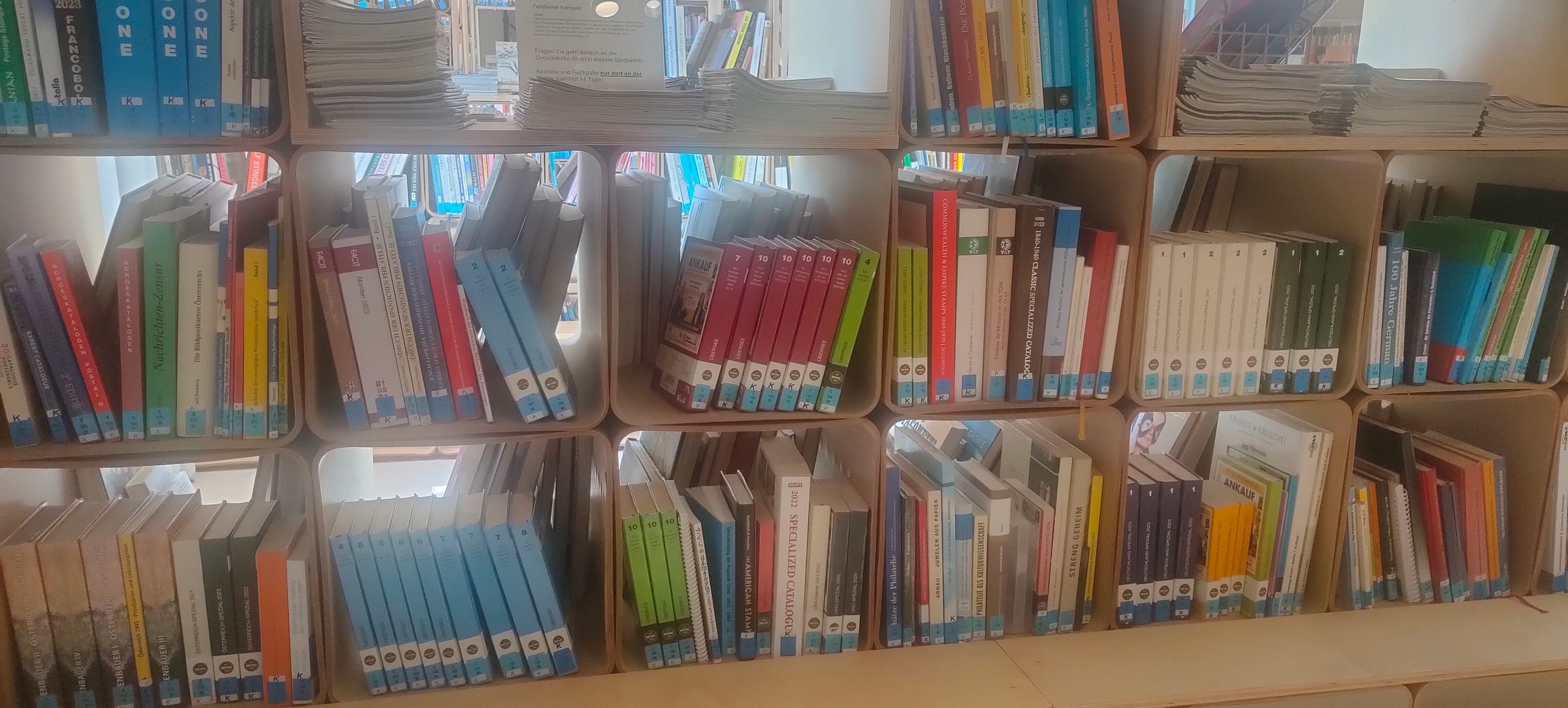

Pfeffer gave me an overview of the library and its current state. When I eagerly asked Pfeffer where the philatelic collections were, he pointed to one case (actually, one half of a case since non-philatelic books are stacked on the facing side) containing about 550 items (Figure 12); seeing it tempered my enthusiasm somewhat.

The books on the case are mostly stamp catalogs (Figure 13), which is understandable since these are usually the most consulted and borrowed ones. But I also saw some standard handbooks, such as Dr. Ulrich Ferchenbauer’s four-volume Österreich Handbuch und Spezialkatalog, and digital media. Apparently, the five most important German philatelic magazines are also somewhere in there. The remainder of the 64,000 odd items are in an “internal stacks building” many miles away in Oberschleissheim on the northern outskirts of Munich. There is no reading room at HP8. Just a few chairs and a small table are set near the philatelic shelf. The current premises where the MPL is located is undoubtedly a pale shadow of its former self.

Budget and Acquisitions

Since the city library is run by the municipality of Munich, the philatelic library doesn’t face the kind of budget constraints for the purchase of items that plague many other libraries. Not that the funds are boundless.

For the year 2023 the municipality has provided 10,000 euros and another 2,300 euros has been granted by Bonn-based Stiftung zur Förderung der Philatelie und Postgeschichte (Foundation for the Promotion of Philately and Postal History).14 In the previous two years, the foundation provided the same amount each year while the municipality allotted 8,000 euros in 2022 but only 1,800 in 2021; the latter number was perhaps a result of the Covid-19 lockdowns, move from Gasteig to HP8, etc.

The MPL’s yearly acquisition rate has tumbled sharply in recent times. From 1,000 to 1,500 items until a few years ago, this number has fallen to 575 in 2020, 266 in 2021, 380 in 2022, and is expected to be about 400 in 2023. This is probably to do with a combination of funds and staffing.

So, for instance, the library used to receive more than about 500 journals in 2019, half in German and half in other languages. Since 2022, Pfeffer mentioned that he had to cut them down to about 180. One reason is the requirement of making foreign currency payments to overseas suppliers. This involves the intervention of the library’s finance department and gets time consuming.

(Of the 180 journals, about 60 are meant to be long-term archived i.e. bound and stacked. As for the rest, only the latest volumes are stored; perhaps the last three to four years, but this depends on the number of issues per year.)

Pfeffer says that digital journals will play an increasingly important role in the future. They don’t take space (which is scarce in the stacks) and don’t require work such as binding etc. Currently a project is underway with the e-services department of the city library to make digital journals available as PDF files to the library’s customers via a suitable software. Until now, about 40 journal titles have been acquired and archived only digitally.

Books, including those housed at Oberschleissheim, can, of course, still be borrowed. But filling in the orders takes longer than earlier. Valuable or old items that can’t be taken home can be ordered to be viewed in the reading room of the Monacensia library (one of the 25 locations from which the city library operates). Due to the financial support given by the Federation of German Philatelists (BDPh) in the past, its members can borrow books for free, paying only the postage. Interlibrary loans are also given, usually to German addresses. Last year, the library made 85 such loans comprising 284 volumes.

What next for the MPL?

Currently, the philatelic library’s future seems to be uncertain. In what form will the City Library and the MPL move back into the renovated Gasteig? The best-case scenario will be if it gets the space that it had earlier.

How long will that take? Given the current situation, it could be well into the 2030s.

Importantly, will the number of employees in the philatelic department go back to four or even three or two? Since the MPL is so big and because the employees of the section have always done everything – purchasing, inventorying, cataloging, processing, and making the books available – one person can’t possibly keep the show going on for long. At least in the way it was being done until a few years back.

The glass half-full part of me is optimistic and hopes that the library reaches its intended destination (as I did despite moving in the wrong direction first!).

The glass half-empty part thinks that philately and philatelic literature don’t rank high in anyone’s consciousness these days, least of all the bureaucracy. The tribe of collectors and philatelists and postal historians has also been showing a precipitous decline over the last two to three decades. Though I believe that those who are around are, on average, more serious about the hobby wanting to go in great depth whilst trying to understand their areas of interests (which requires access to a lot of philatelic literature), nevertheless diminishing numbers is calling the need for physical philatelic libraries into question.

So, who will advocate for the Munich Philatelic Library? It’s mainly up to German philatelists and societies and organizations such as Federation of German Philatelists (BDPh) to lobby the powers that be to at least preserve the library as it was until a few years back. Perhaps a public-private partnership could be the way forward?

MPL online catalog

In 1938, the first catalog of the MPL’s holdings titled Katalog der Philatelistischen Abteilung der Stadtbibliothek München (Catalog of the Philatelic Department of the Munich City Library) was published. Comprising 192 pages, it was typewritten and is undoubtedly Mueller’s work.

The task of cataloging and indexing the library’s holdings that started with Mueller continued through his successors. In 1966, a catalog of the library’s holdings covering Germany and German areas was produced by Walter Merkle; a second edition by Otto Gleixner and his co-worker Lieselotte Jackson-Lindner, followed in 1974. Meanwhile, catalogs covering Great Britain and Switzerland came out in 1971, France in 1974, and overseas countries in 1975. Printed catalogs continued to be issued until 1990.

Since 2003, the library’s holdings can be seen on the city library’s online public access catalog (OPAC) at muenchner-stadtbibliothek.de/katalog (Figure 14). The catalog runs on the library management system – aDIS/BMS – developed by the company aStec angewandte Systemtechnik eG.

The website is in German but web browsers these days can translate web pages into English (or any other language) on the fly; either on their own ability or by using an extension, or add-on. A quick internet search will show anyone how to.

Pfeffer showed me how the library’s holdings can be searched. Since it can prove useful to researchers, I am giving an overview here.

Searching the MPL’s holdings

Clicking on “Erweiterte Suche” takes one into the advanced search page (Figure 15).

To search only the philatelic items in the city library’s database, enter “Philatelie” in the search box against “Systematik” (select the latter from the drop down). Due to technical reasons, not all the 65,000-odd items of the philatelic library are displayed; only 32,000.

Basic Search

Searching using the title of the publication or the author is straight forward. One can also filter per the type (Medienart) such as book or CD-ROM or online-resource, or language (Sprache), or the year of publication.

Users will see that some of results give additional information. For example, I searched for the very rare early German stamp catalog – Handbuch für Briefmarken-Sammler: Anweisung zur zweckmässigsten Einrichtung der Briefmarken-Sammlungen nebst vollständiger Uebersicht und Beschreibung aller bis jetzt ausgegebenen Briefmarken.

Inputting the first three words – Handbuch für Briefmarken-Sammler – gave me three hits, of which I chose the first one since I could see the year “1863” against that result (Figure 16). Apart from the usual output, one can note extra details. For instance, the book’s provenance, that the pages aren’t acid free, and that it’s a rare publication and hence in a steel cabinet.

(There are about 100 items considered most rare and are stored in the steel cabinet. These are mostly 19th century printed works from the early days of stamp collecting going back to 1863. In addition, the cabinet holds some valuable 20th century titles, such as Tracy Woodward’s two-volume The Postage Stamps of Japan and Dependencies published 1928 and Carl Schmidt’s Die Postwertzeichen der russischen Landschaftsaemter published 1932. Another approximately 1,900 items are considered rare.)

Finally, photos of some publications are scanned in the catalog; this is especially true for those published in recent years.

Now, on to more advanced search. The catalog enables collectors to search, in a precise manner, for literature based on their collecting interests. This is because of the detailed way in which items have been indexed.

Keyword search

For each item, at least one of the about 250 philatelic keywords (Schlagwort) have been assigned; usually more, sometimes even four or five.

Someone interested in military mail may want to search for resources on field posts.

The searcher would input “Philatelie” against “Systematik” and then in the next search box, “Feldpost” (field post) against “Schlagwort / Thema”, then click on the search button (Suchen) at the bottom. The catalog outputs 704 results as of a recent search.

On the right side, filter options – such as media type, more keywords, year of publication, etc. – are available (Figure 17). Results can also be sorted in terms of relevance, title, author, or year using additional filters.

The list of keywords can be downloaded as a PDF file from the MPL’s website at muenchner-stadtbibliothek.de/philatelistische-bibliothek. A few samples are given in this table under “A”.

Sub-groups

Secondly, items have been sub-grouped into one of 22 topics. Again, the PDF file containing these as well as their respective codes are available for download; the table shows a few under “B”.

How does one go about searching using sub-groups? For instance, if one wants to see books from across the world on ship posts / maritime mails.

Find the code for “Schiffspost” from the said PDF file; that’s “14.” Then input “Philatelie” and “14” in two different search boxes, both against “Systematik”. This recently resulted in 518 hits. On the first results page, one notes titles such as North Atlantic Non-contract Steamship Sailings 1838-1875, published 2022, and The Egyptian Maritime Postal History (1845-1889), published 2019.

Philatelic systematics

Finally, each item has its place in the philatelic systematics (Philatelistische Systematik). With the philatelic systematics / classification lists (Systematiklisten), that can also be downloaded from the same site, one can search for items of their interest by inputting the corresponding code against the field “Systematik” (systematic); the table shows some under C1-C5.

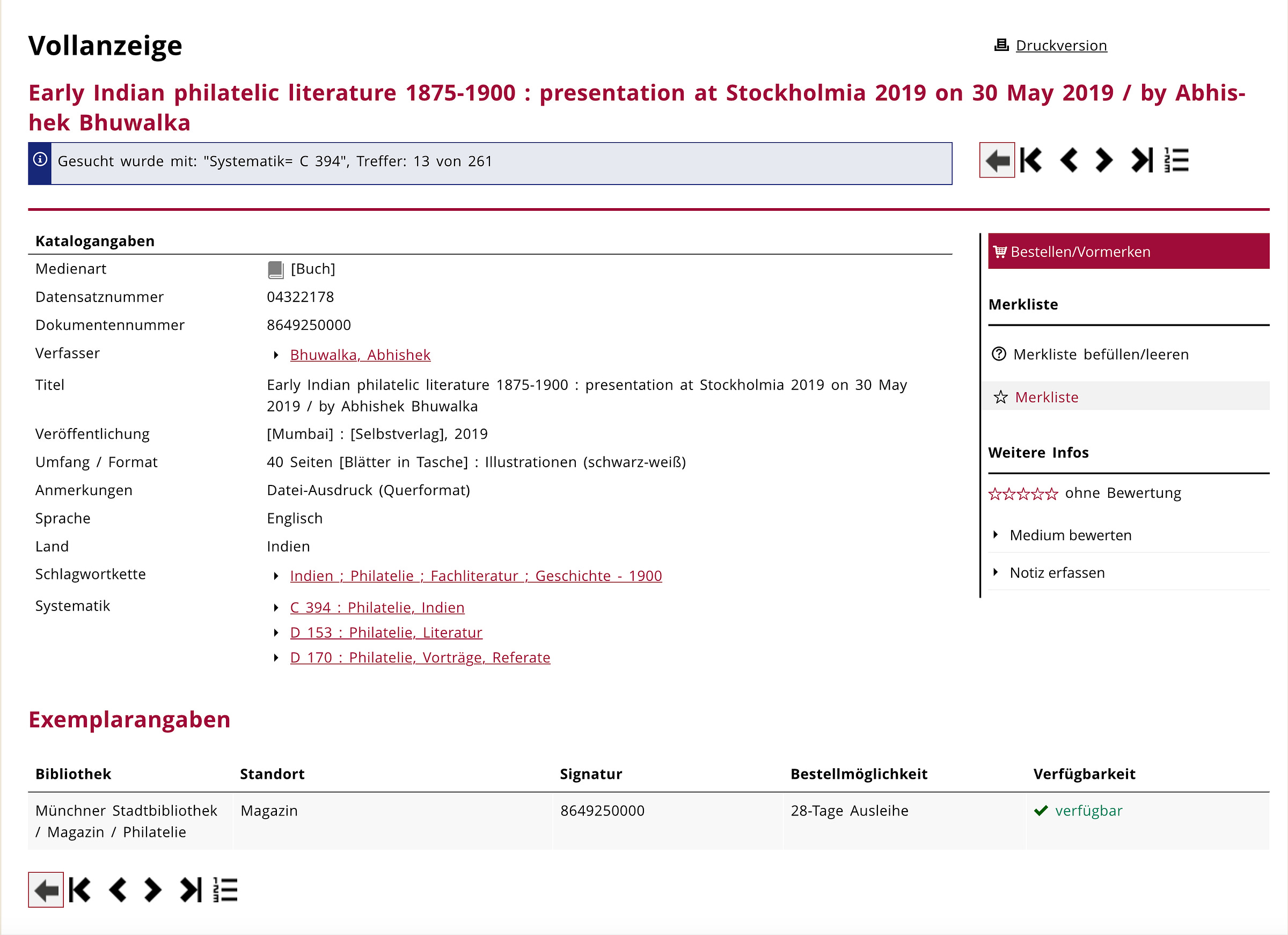

So, for example, if one is interested in all titles concerning India (Indien), one needs to find the code for it (C 394) and input it against “Systematik.” This gives 261 hits.

Another way to make a similar search is to first input “Philatelie” and then “Indien,” both against “Systematik.” This gives more hits – 603 – since items not classified under C 394 but elsewhere must have “Indien” associated with them. For example, one hit is Catalogue de Timbres-Poste (Catalog of Postage Stamps) by the French publisher – Yvert & Tellier in 2022. What does that have to do with “Indien”? Drilling into the result shows that the catalog covers French India (Französisch-Indien) and hence its appearance when this search is run.

I was surprised to see my name when I did the “C 394” search! Printouts of a PowerPoint presentation I gave at Stockholmia 2019 (Figure 18). Who did that?

As one can see, there are four keywords associated with this item – “Indien” (India), “Philatelie” (philately), “Fachliteratur” (technical literature), and “Geschichte – 1900” (History – 1900). Further under “Systematik,” this item (as are most others) shows up at multiple levels: “Indien” (India; C 394), “Literatur” (Literature; D 153), and “Vorträge, Referate” (Lectures and Presentations; D170).

Acknowledgements: Many thanks to Joergen Pfeffer, first for his warm welcome when I visited the library, and for also going through the draft of this article and providing many suggestions. He can be contacted at stb.phil.kult@muenchen.de. Thanks to Wolfgang Maassen for providing me with photographs from his massive digital archive.

References

Books and Articles

Binner, Robert and Sabine Rüsch. “Ein Eldorado für Briefmarkenfreunde.” Bibliotheksforum Bayern. Heft 3 (2012): 192-196. bibliotheksforum-bayern.de/archiv.

Birch, Brian J. Philatelic Translations Produced by Brian J. Birch. Montignac Toupinerie, France: The Author, 2018. [This has been most useful as it contains translations of many German works which helped me trace the history of the MPL and the associated personalities. The works used are too numerous to be all individually listed here.]

———. The Philatelic Bibliophile’s Companion. Montignac Toupinerie, France: the Author, 2018.

Maassen, Wolfgang. “Philatelistische Bibliotheken – von Sammlern und für Sammler!” in Häuser der Philatelie: Eine Heimat für Sammler. Schriftenreihe zur Geschichte der Philatelie in Deutschland Nr. 4. Bonn: Consilium Philatelicum, Bund Deutscher Philatelisten, 2004. Available as Philat. Transl. 519 in Philatelic Translations Produced by Brian J. Birch.

———. “Der „Herr der Bücher”: Ein Besuch in der Philatelistischen Bibliothek München.” philatelie 402 (December 2012): 52-55.

———. Wer Ist Wer in Der Philatelie? Band 1. A-D. Third. Vol. 1. 6 vols. Chronik Der Deutschen Philatelie. Schwalmtal: Phil*Creativ GmbH, 2011.

———. Wer ist Wer in Der Philatelie? Band 2. E-H. Third. Vol. 2. 6 vols. Chronik Der Deutschen Philatelie. Schwalmtal: Phil*Creativ GmbH, 2017.

———. Wer ist Wer in Der Philatelie? Band 3. I-L. Third. Vol. 3. 6 vols. Chronik Der Deutschen Philatelie. Schwalmtal: Phil*Creativ GmbH, 2020.

———. Wer ist Wer in Der Philatelie? Band 4. M-R. Third. Vol. 4. 6 vols. Chronik Der Deutschen Philatelie. Schwalmtal: Phil*Creativ GmbH, 2021.

———. Wer ist Wer in Der Philatelie? Band 5. S. Third. Vol. 5. 6 vols. Chronik Der Deutschen Philatelie. Schwalmtal: Phil*Creativ GmbH, 2022.

———. Wer ist Wer in Der Philatelie? Band 6. T-Z. Third. Vol. 6. 6 vols. Chronik Der Deutschen Philatelie. Schwalmtal: Phil*Creativ GmbH, 2022.

[Mueller, Christoph Otto]. Katalog der philatelistischen Abteilung der Stadtbibliothek München, Weinstraße 13: nach dem Stand vom 1. Dezember 1938. Munich: Münchner Stadtbibliothek, 1939. Introductory text available as Philat. Transl. 563 in Philatelic Translations Produced by Brian J. Birch.

Mueller, Christoph Otto. “Aus den Erinnerungen eines philatelistischen Berufsbibliothekars.” Das Sammler-Lupe 8 no. 12 (June 1953): 182. Available as Philat. Transl. 568 in Philatelic Translations Produced by Brian J. Birch.

Web pages

MünchenWiki. “Münchner Stadtbibliothek.” Accessed July 31, 2023. muenchenwiki.de/wiki/Münchner_Stadtbibliothek.

Münchner Philatelistische Bibliothek at Münchner Stadtbibliothek. muenchner-stadtbibliothek.de/philatelistische-bibliothek.

Münchner Stadtbibliothek. “Hans Ludwig Held - eine Ausnahmepersönlichkeit.” Accessed August 4, 2023. blog.muenchner-stadtbibliothek.de/meiden-sie-meinen-mann-wenn-er-hochdeutsch-spricht.

It’s easy to consider that in case of handbooks, one media item is one volume on the shelf. However, it’s not so for journals. The entire run of a journal may or may not constitute one media item. Short run journals may but in the case of longer run ones, one media item may be issues over a few years bound together or sometimes issues of just one year.

A search of the library’s online catalog indicates that about 43 percent of the media items are in German, 33 percent in English, and 9 percent in French.

Binner (2012) mentions that the library celebrated its 80th anniversary in November 2011.

Otto’s surname was Müller. However, when German umlauts (ä, ö, and ü) are changed into English, ü is written as ue, hence Mueller. Also, ö (for example, in Jörgen) is written as oe and ä (as in Ägypten) as ae. Finally, the letter ‘ß’ (as in say, Straße or street; also, Maßen as Massen) as ss.

In his reminiscences, Mueller (1953) says that 47 years back a stamp-friendly Santa Claus awakened in him a passion for collecting. This would mean 1906, when Mueller was 12.

Münchner Ganzsachensammler-Verein has existed since 1912 and caters to members who specialize in postal stationery. See mgsv.de for more information.

Münchener Briefmarken-Club e.V. was founded in 1905 and is still going strong. It can be found on the internet at mbc1905.de.

Berliner Philatelisten-Klub is one of the oldest philatelic societies in the world having been founded in 1888. In 1905, the society founded the Lindenberg Medal in honor of Carl Lindenberg, a respected German philatelist. The medal is awarded for outstanding philatelic contributions and is one of the most important recognitions in philately. The club can be found on the internet at berliner-philatelisten-klub-1888.de.

Bund Deutscher Philatelisten (BDPh), founded in 1946, is the is the umbrella organization of about 860 local associations and philatelic working groups in Germany. Based in Bonn, it aims to represent interests of all philatelists in Germany by public relations work, through philatelic events, and through cooperation with other philatelic organizations. It also publishes the monthly journal philatelie. More information on this organization is available on bdph.de.

The website of the BDPh currently hosts a databank of Literatur-Nachrichten from 2005 onwards.

The Gasteig is Europe’s biggest cultural complex measuring about 90,000 square meters (just less than 1 million square feet). Owned by the city of Munich, it hosts the central location of the Munich city library (which includes the MPL), Munich Philharmonic Orchestra, Munich Volkshochschule (adult education centre), and Hochschule für Musik und Theater (University for Music and Theatre). The origin of its name is interesting. The Gasteig is built on a hill above the river Isar. There used to be a steep path between the hill and the river. This path was called the gacher Steig (steep path or climb). Overtime, this changed to Gasteig.

Actually, it’s one-and-half posts. The head of the MPL is supposed to work 70 percent of the time for the philatelic section and 30 percent of the time for the city library while his colleague needs to work 50 percent for the MPL and 50 percent doing ‘normal’ stuff for the city library.

The city library also opened an interim location at Motorama, which is a shopping mall just opposite the Gasteig on Rosenheimer Strasse. As per documents available on the Gasteig website right now, the total costs of the interim arrangements amounted to 112 million euros.

Stiftung zur Förderung der Philatelie und Postgeschichte was set up by the (West) German Ministry for Post and Telecommunications in 1966. From the very beginning, the foundation was intended to be a public-private partnership. Its board of trustees comprise members from Deutsche Post AG, the German Ministry of Finance (Bundesministerium der Finanzen), the Post and Telecommunication Museum Foundation (Museumsstiftung Post und Telekommunikation), and the Federation of German Philatelists (BDPh). Over the last 50 years, the foundation has distributed over 50 million euros for the promotion of philately and postal history. Its website is philatelie-stiftung.de.